Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills of Dreamland

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) The Hills of Dreamland SOMMCD 271-2 The Hills of Dreamland Orchestral Songs The Society Complete incidental music to Grania and Diarmid Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano† • Henk Neven baritone* ELGAR BBC Concert Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth conductor ORCHESTRAL SONGS CD 1 Orchestral Songs 8 Pleading, Op.48 (1908)† 4:02 Song Cycle, Op.59 (1909) Complete incidental music to 9 Follow the Colours: Marching Song for Soldiers 6:38 1 Oh, soft was the song (No.3) 2:00 *♮ * (1908; rev. for orch. 1914) GRANIA AND DIARMID 2 Was it some golden star? (No.5) 2:44 * bl 3 Twilight (No.6)* 2:50 The King’s Way (1909)† 4:28 4 The Wind at Dawn (1888; orch.1912)† 3:43 Incidental Music to Grania and Diarmid (1901) 5 The Pipes of Pan (1900; orch.1901)* 3:46 bm Incidental Music 3:38 Two Songs, Op. 60 (1909/10; orch. 1912) bn Funeral March 7:13 6 The Torch (No.1)† 3:16 bo Song: There are seven that pull the thread† 3:33 7 The River (No.2)† 5:24 Total duration: 53:30 CD 2 Elgar Society Bonus CD Nathalie de Montmollin soprano, Barry Collett piano Kathryn Rudge • Henk Neven 1 Like to the Damask Rose 3:47 5 Muleteer’s Serenade♮ 2:18 9 The River 4:22 2 The Shepherd’s Song 3:08 6 As I laye a-thynkynge 6:57 bl In the Dawn 3:11 3 Dry those fair, those crystal eyes 2:04 7 Queen Mary’s Song 3:31 bm Speak, music 2:52 BBC Concert Orchestra 4 8 The Mill Wheel: Winter♮ 2:27 The Torch 2:18 Total duration: 37:00 Barry Wordsworth ♮First recordings CD 1: Recorded at Watford Colosseum on March 21-23, 2017 Producer: Neil Varley Engineer: Marvin Ware TURNER CD 2: Recorded at Turner Sims, Southampton on November 27, 2016 plus Elgar Society Bonus CD 11 SONGS WITH PIANO SIMS Southampton Producer: Siva Oke Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Booklet Editor: Michael Quinn Front cover: A View of Langdale Pikes, F. -

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Solving Elgar's Enigma

Solving Elgar's Enigma Charles Richard Santa and Matthew Santa On June 19, 1899, Elgar's opus 36, Variations on a Theme, was introduced to the public for the first time. It was accompanied by an unusual program note: It is true that I have sketched for their amusement and mine, the idiosyn crasies of fourteen of my friends, not necessarily musicians; but this is a personal matter, and need not have been mentioned publicly. The Varia tions should stand simply as a "piece" of music. The Enigma I will not explain-its "dark saying" must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set [of variations 1 another and larger theme "goes" but is not played ... So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some late dramas-e.g., Maeterlinck's "L'Intruse" and "Les sept Princesses" -the chief character is never on the stage. (Burley and Carruthers 1972:119) After this premier Elgar give hints about the piece's "Enigma;' but he never gave the solution outright and took the secret to his grave. Since that time scholars, music lovers, and cryptologists have been trying to solve the Enigma. Because the solution has not been discovered in spite of over 108 years of searching, many people have assumed that it would never be found. In fact, some have speculated that there is no solution, and that the promise of an Enigma was Elgar's rather shrewd way of garnering publicity for the piece. -

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal Script Not for Performance Use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal script Not for performance use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Duplication and distribution prohibited. In addition to the orchestra and conductor: Five performers Edward Elgar, an Englishman from Worcestershire, 41 years old Actor 2 (female) playing: Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer's wife Carice Elgar, the composer's daughter Dora Penny, a young woman in her early twenties Snobbish older woman Actor 3 (male) playing: William Langland, the mediaeval poet Arthur Troyte Griffith (Ninepin), an architect in Malvern Richard Baxter Townsend, a retired adventurer William Meath Baker, a wealthy landowner George Robertson Sinclair, a cathedral organist August Jaeger (Nimrod), a German music-editor William Baker, son of William Meath Baker Old-fashioned musical journalist Pianist Narrator Page 1 of 21 ME 1 Orchestra, theme, from opening to figure 1 48" VO 1 Embedded Audio 1: distant birdsong NARRATOR The Malvern Hills... A nine-mile ridge of rock in the far west of England standing about a thousand feet above the surrounding countryside... From up here on a clear day you can see far into the distance... on one side... across the patchwork fields of Herefordshire to Wales and the Black Mountains... on another... over the river Severn... Shakespeare's beloved river Avon... and the Vale of Evesham... to the Cotswolds... Page 2 of 21 and... if you're lucky... to the north, you can just make out the ancient city of Worcesteri... and the tall square tower of its cathedral... in the shadow of which... Edward Elgar spent his childhood and his youth.. -

The Brass Band Bridge with a in This Issue Tremendous Number of Reviews of New Brass Band Recordings

A S E B R S B A T H N D BRIDGE H issue 110 The Official Publication of the North American Brass Band Association august, 2008 Once again, Ronald W. Holz has provided UNDER THE BRIDGE readers of The Brass Band Bridge with a IN THIS ISSUE tremendous number of reviews of new brass band recordings. I’d like to add a hearty, “hear, Douglas Yeo hear” to his enthusiastic recommendation of ATOP THE BRIDGE the new recording of Elgar’s Severn Suite, with From the President, pg. 2 Editor Black Dyke Band, conducted by Sir Colin Davis. This performance is revelatory, and having worked with Sir Colin myself when he RECORDING OF THE his issue of The Brass Band Bridge fea- has guest conducted the Boston Symphony YEAR CONTEST tures reports from several recent brass (including memorable performances of Elgar’s pg. 3 band festivals which were sponsored, in Enigma Variations and The Dream of Gerontius), Tpart, by NABBA. The Great American Brass I can very well imagine how the Black Dyke Band Festival is the premier brass band festival players felt when sitting under the leading NEWS FROM NABBA in the USA and it always features performances interprer of Elgar in our time. The recording BANDS by at least one of NABBA’s most distinguished is truly stupendous. Ron’s reviews are also a bands. The Fifth Toronto Festival of Brass fea- reminder to all NABBA member bands to get pg. 5 tured world premiere performances, and several in their entries for NABBA’s “Recording of the youth bands. -

Vol. 18, No. 1 April 2013

Journal April 2013 Vol.18, No. 1 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2013 Vol. 18, No. 1 Editorial 3 President Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Julia Worthington - The Elgars’ American friend 4 Richard Smith Vice-Presidents Redeeming the Second Symphony 16 Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Tom Kelly Diana McVeagh Michael Kennedy, CBE Variations on a Canonical Theme – Elgar and the Enigmatic Tradition 21 Michael Pope Martin Gough Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Music reviews 35 Leonard Slatkin Martin Bird Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Donald Hunt, OBE Book reviews 36 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Frank Beck, Lewis Foreman, Arthur Reynolds, Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE D reviews 44 Martin Bird, Barry Collett, Richard Spenceley Chairman Letters 53 Steven Halls Geoffrey Hodgkins, Jerrold Northrop Moore, Arthur Reynolds, Philip Scowcroft, Ronald Taylor, Richard Turbet Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 57 Treasurer Clive Weeks The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Secretary nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Helen Petchey Front Cover: Julia Worthington (courtesy Elgar Birthplace Museum) Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. -

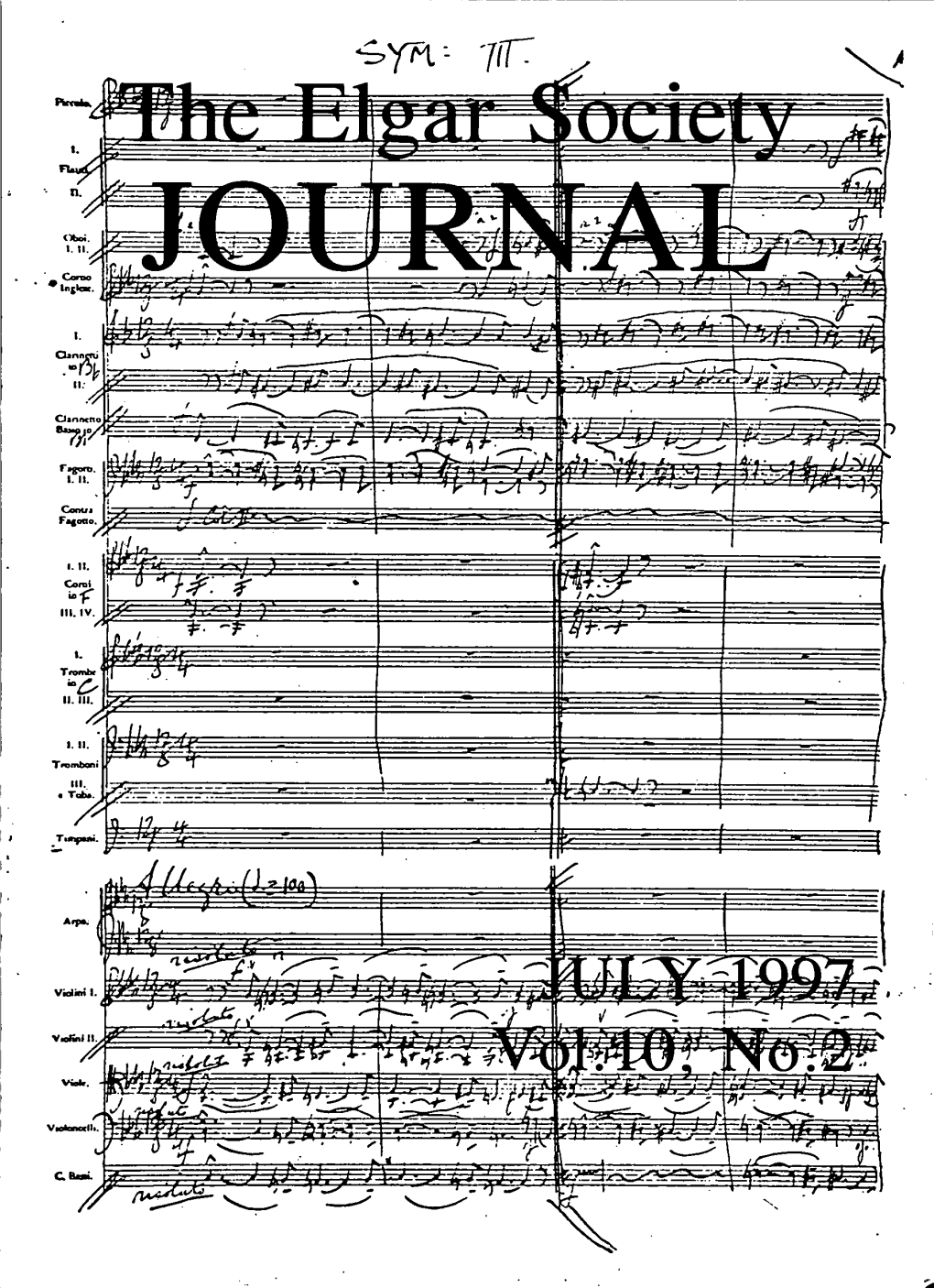

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

(C) First Edition Riddle's Collection of Scots Playford's Scotch Tunes of 1700 and 1701, Aria Reels, C

CJj'e •fllustca/.. Vol. VII., No. 2. ist OCTOBER 1925. Pkice Fourpence. NEW EDUCATIONAL WORKS Just Published ij.—NOVELLO'S MUSIC PRIMERS. No. 101.—NOVELLO'S MUSIC PRIMERS. BREATHING FOR VOICE-PRODUCTION EAR-TRAINING (Rewritten and brought up to date) EURHYTHM: THOUGHT IN ACTION. MUSICAL APPRECIATION AND By H. H. HULBERT. RHYTHMIC MOVEMENTS. Price ... Three Shillings. Paper Buards, 45. MABEL CHAMBERLAIN. Just Published. Complete, Six Shillings, Or No. 100.—NOVELLO'S MUSIC PRIMERS. In Two Books: Letterpress and Illustrations, as. Music only, 35. PRONUNCIATION FOR The Ear-Training Course outlined in this book is intended VOICE-PRODUCTION primarily for Class use, but if a judicious selection be made from FROM the exercises, the course can be used with equal benefit by private EURHYTHM : THOUGHT IN ACTION. teachers for individual pupils. Senior pupils and students who desire to Study music, and who have received little or no previous By H. H. HULBERT. tuition, cannot do better than work rapidly through these progress- ive exercises and tests. A Prospectus will be sent on application. Pkice, One Shilling and Sixpence. LONDON NOVELLO & COMPANY LIMITED A valuable Work of Reference for all School and Music Teachers The " His Master's Voice " Education Catalogue has been compiled especially for the use of Teachers and Stu- dents who are using the Gramophone. It is intended to be a simple guide to a "His very large number of Records that have Master's been chosen for their educational value. Voice" The above Catalogue can be obtained free from all "His Master's Voice" accredited dealers, or from The Gramophone Company, Ltd. -

Vol.21 No 2 August 2018

Journal August 2018 Vol. 21, No. 2 The Elgar Society Journal 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] August 2018 Vol. 21, No. 2 Cross against Corselet: Elgar, Longfellow, and the Saga of King Olaf 3 President John T. Hamilton Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Elgar’s King Olaf – an illustrated history 15 John Norris, Arthur Reynolds Vice-Presidents To the edge of the Great Unknown: 1,000 Miles up the Amazon 27 Diana McVeagh Martin Bird Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Book reviews 41 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Barry Collett Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE CD reviews 43 Andrew Neill Barry Collett, Andrew Neill, Michael Schwalb Sir Mark Elder, CBE Martyn Brabbins DVD reviews 54 Tasmin Little, OBE Ian Lace Letters 56 Jerrold Northrop Moore, Andrew Neill, Arthur Reynolds Chairman Steven Halls Elgar viewed from afar 58 Alan Tongue, Martin Bird Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 69 Martin Bird Treasurer Helen Whittaker Secretary George Smart The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Front Cover: Edward William Elgar (1857-1934; Arthur Reynolds’ Archive) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882; Charles Kaufmann’s Archive). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Cross against Corselet required, are obtained. Elgar, Longfellow, and the Saga of King Olaf Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, cued into the text, and have captions.