Comprehensive School Reform: a Study on the Effectiveness of the High Schools That Work Program in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vernon College 2021-2022 HERC

Page 1 of 12 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION REGIONAL COUNCIL OFF-CAMPUS INSTRUCTIONAL PLAN FOR 2020-2021 Institution Name: Vernon College Regional Council: Northwest Texas Higher Education Council Contact Person: Shana Drury Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 940-552-6291 ext 2314 Delivery location: Program Area: Award(s): Program Status: Delivery Geographically Agreement in place/ Site name and community. CIP#/Title (AAS, Cert1, Type: [C], [N], Type: Responsible Agreement type Highlight locations added etc.) [DC], [LD], [D]₂ [F2F], [E2G], Institution₄ since last report. [UD], [NC]1 [CLN]₃ Programs requiring HERC approval Programs requiring HERC notification Vernon, TX – AA – Associate in Arts AA, AS, AAT DC, LD C F2F, E2G Vernon College N/A Vernon High School 24.010200 Northside High School Harrold, TX – AS – Associate in Science Harrold High School 24.010200 Wichita Falls, TX – Century City Center, AAT – Associate of Arts in Career Education Center, Teaching Christ Academy, 13.121000 City View High School, 13.120300 Dexter School 13.120600 Hirschi High School, Notre Dame Catholic Core Curriculum School, S.H. Rider High School, Skills Training Center, Texas Home School, Wichita Falls High School, Wichita Christian School Archer City, TX – Archer City High School Benjamin, TX- Benjamin High School 1 Course Type: Dual Credit [DC], Lower Division Credit [LD], Upper Division or Graduate Credit [UD], Non-Credit [NC] 2 Course Status: Current offering [C], New offering in upcoming year [N], Deleted offering for upcoming year [D] 3 Delivery Type: Face-to-Face [F2F], Electronic-to-Groups [E2G], Clinical [CLN] 4 Community College District in whose Service Area the site is located. -

April, 1992 • ISSN 0897-4314 Efteia Two on Sportsmanship

EBguer State Meet one-act play schedule School productions a great bargain MAY 7, THURSDAY (Note: PAC - Performing Arts Center) 7:30 am — AAA company meet ing and rehearsals: Concert Hall, south entrance of the PAC. 4:00 pm — AAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. 7:30 pm — AAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. MAY 8, FRIDAY 7:30 am — AA company meeting and rehearsals: McCullough Theatre, northeast corner of the PAC AAAA company meeting and re hearsals: Bass Concert Hall, south en trance of the PAC. 9:00 am — 12:00 noon Conference AAA critiques: Bass Concert Hall, Lobby Level. 4:00 pm — AA contest, four plays: •McCullough Theatre. AAAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. 7:30 pm—AA contest, four plays: 'McCullough Theatre. The FIRST time is the charm AAAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. Longview, San Marcos claim 5A titles in initial appearances MAY 9, SATURDAY 7:30 am — A company meeting BY PETER CONTRERAS SOC it to 'em. Members of the Dallas and rehearsals: McCullough Theatre, Director of Public Information South Oak Cliff team (above) celebrate their northeast corner of the PAC. state 4A finals win over Georgetown. (Left) AAAAA company meeting and A pair of first-time players, Longview in the Duncanville's Lana Tucker drives in the rehearsals: Bass Concert Hall, south boy's tournament and San Marcos in the girl's Pantherette's loss to San Marcos in the 5A girls championship game. entrance of the PAC. tournament, handled the pressure of participating Photos by Joey Lin. 9:00 am —12:00 in the UIL State Basketball Championships without any problem in claiming class 5A state noon Conference AA and AAAA cri join the football title won in December. -

Techline Installation List

>/ŶƐƚĂůůĂƚŝŽŶ dLJƉĞ&ŝĞůĚ ŝƚLJ ^ƚĂƚĞͬŽƵŶƚƌLJ Abilene Chrisitan University Football Abilene Texas Addison High School Football Addison Michigan Alvin ISD Football Alvin Texas Amador Valley High School Football Pleasanton California Anguilla Football Association Football The Valley Anguilla Aqua Golf Driving Range Denver Colorado Ashland High School Football Ashland Oregon Atlanta Falcons Football Atlanta Georgia Banquete High School Football Robstown Texas Bay Village City Schools Football Bay Village Ohio Beale Air Force Base AFB Beale AFB California Belleville West High School Tennis Belleville Illinois Billy Bowlegs Park Football, Soccer, Basketball Ft. Myers Florida Birmingham Community Charter School Football Van Nuys California Bishop Kelley Stadium Football Tulsa Oklahoma Brentwood School Football, Tennis, Pool Los Angeles California Brentwood School Softball Los Angeles California Brewster Field Soccer, Tennis Belleair Florida Brookville Park Tennis Bourough of Queens New York Brunswick High School Softball Brunswick Georgia Buhler High School Baseball Buhler Kansas Cabot High School Football Cabot Arkansas Cal State Monterey Bay Baseball, Softball, Soccer Monterey Bay California Camp Pendleton Pool Oceanside California Campus High School Tennis Haysville Kansas Capitol Hill High School Gym Oklahoma City Oklahoma Castle Hill Park Baseball New York New York Castleberry High School Soccer Ft. Worth Texas Central Broward Regional Stadium Cricket Lauderhill Florida Central Catholic High School Football San Antonio Texas Chaffey -

Tim Jetton, M.Ed. Angelo State University College of Education Department of Curriculum and Instruction [email protected] Education

Tim Jetton, M.Ed. Angelo State University College of Education Department of Curriculum and Instruction [email protected] Education M. Ed. Educational Administration, Lamar University, Beaumont, TX, 2011 BS Kinesiology & Biology, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, TX, 1996 Professional Certifications Texas EC-12 Principal State Board for Educator Certification – 2011 Biology State Board for Educator Certification – 1996 Life / Earth Science State Board for Educator Certification – 1996 Secondary Physical Education State Board for Educator Certification – 1996 Professional Experience Adjunct Instructor C&I, Angelo State University, San Angelo, Tx. Assist the lead professor and instructor with student contact and scoring Courses Taught (online): Leadership 6363 Fall B 2017 Principal Grape Creek Independent School District, San Angelo, TX, 2016 – 2018 Facilitate the development, implementation, and evaluation of quality instruction through T-TESS evaluations, setting goals to improve performance, and collaboration with teachers. Use a balanced blend of motivational and targeted instruction methodologies to enhance curricula with emphasis on the three ‘R’s - rigor, relevancy and relationships. Utilize “Loose-Tight” leadership to enhance the shared decision-making process. In other words, the leader determines the destination while the teachers determine how to get there. Work closely with district leaders, professional staff, and community partners to increase student success, encourage parental involvement, and build strong community alliances. Demonstrate collaborative leadership and strategically empower others in decision-making. Make decisions based on what is best for all students. Hire and retain superior staff. Maintain high expectations of self, employees and students. Work closely with parents to secure a high level of parental involvement. Identify, create, and evaluate best practices and overall effectiveness of all school departments and programs. -

Wichita District 19 Chapters 28 Teachers

Wichita District 19 Chapters 28 Teachers Archer City High School High School - TX1054 Box 926 AST Information Archer City, TX 76351 Clifton Russell ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 574-2213 Ext. 1044 FAX: (940) 574-4051 Bellevue High School High School - TX0067 PO Box 38 AST Information Bellevue, TX 76228 Nathan Hindman ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 928-2104 Ext. 3 FAX: (940) 928-2583 Burkburnett High School High School - TX0122 109 Kramer Road AST Information Burkburnett, TX 76354 Donnie Loop ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 569-1411 Ext. 1186 Brittany Recer ( [email protected] ) FAX: (940) 569-9700 Chillicothe High School High School - TX0159 PO Box 550 AST Information Chillicothe, TX 79225 Jarrod Baird ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 852-5391 Ext. 233 FAX: (940) 852-5269 City View High School High School - TX1112 1600 City View Drive AST Information Wichita Falls, TX 76306 Lauren Lange ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 855-7511 Ext. 309 Zach Ward ( [email protected] ) FAX: (940) 851-5027 Crowell High School High School - TX0206 PO Box 239 AST Information Crowell, TX 79227 Scott Bearden ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 684-1331 FAX: (940) 684-1616 Electra High School High School - TX0256 400 East Roosevelt AST Information Electra, TX 76360 Chase Witt ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 495-2074 FAX: (940) 495-3303 Harrold High School High School - TX0353 PO Box 400 AST Information Harrold, TX 76364 Russ Ramsey ( [email protected] ) Ag Dept: (940) 886-2213 Ext. -

2018 TSSEC Outstanding Performer Student School Name Event Valeriia Kalinnikova A.C. Jones HS Music Theory Joshua Carrillo Abern

2018 TSSEC Outstanding Performer Student School Name Event Valeriia Kalinnikova A.C. Jones HS Music Theory Joshua Carrillo Abernathy High School Alto Saxophone Nathaniel Diaz Abilene High School Flute Parker Fowlkes Abilene High School French Horn Enrique Ruiz Akins High School Acoustical Guitar Danielle Harrington Aledo High School Vocal Madison Hardick Aledo HS Flute Mazey Rix Aledo HS Keyboard Percussion Amy Mora Allen High School Flute Ryan Liao Allen High School Alto Saxophone Kyle Graham Allen High School Alto Saxophone Gabi Harvatin Allen High School Cornet/Trumpet Brennan Dahl Alvin High School Vocal Charles Johnson Amarillo High School Bass Trombone Mackenzie Nies Amarillo High School Violin Anabelle Gilliam Anderson High School Vocal Alyssa Monfort Anderson High School Vocal Ketty Nguyen Anderson High School Piano Chayton Herbst Angleton High School Vocal Audrey Livingston Argyle High School Flute Madeline Gammage Arlington High School Bb Clarinet Collin Stavinoha Atascocita HS Flute Emma Galbraith Austin High School Violin Sierra Carlson Azle High School Flute Chance Gray Barbers Hill HS Keyboard Percussion Zennia Wong Barbers Hill HS Keyboard Percussion Allen Wang Bellaire HS Piano Andrew Rubio Bellaire HS - Guitar Acoustical Guitar Mariah Montgomery Belton High School Viola Charlie Correa Big Spring HS Vocal Josiah Garcia Big Spring HS Vocal Josh Fonza Boerne High School Piano Shayne Grant Booker T. Washington HSPVA Vocal Kir'Ondria Woods Booker T. Washington HSPVA Vocal Alyssa Merchant Booker T. Washington HSPVA Vocal Chase -

January/February, 1992

Council chairman Butler sets sights on 'critical issues' By JENNIFER R. SANSBURY Larry Butler, the newly elected chairman of the University Interscholastic League's Legislative Council, says he is setting his sights on tackling several "critical issues" dur ing his term. Butler, who is superintendent of the Spearman Independent School District, said he'd "like to see a con tinuation of added aca demic activities, espe cially at the junior level. "Certainly aca demics is a primary issue for the benefit of young people. I think we've made great strides in that." He added that stressing academics is "a trend we're seeing nationwide." The UIL will have to grapple with year- round schools within the next few years, said Butler, who was elected chairman of the Council in October. The Legislative Council is the UIL's 24-member rule-making body. One member from each of the four UIL bas AT HOME IN THE DOME. Killeen's Dion Marion heads around the corner over Sugar Land Dulles. For full state schoolboy championship coverage, please turn to page 11. ketball regions within each of the five con during the Kangaroo's 14-10 5A-1 slate football championship victory ferences is elected to serve a four-year term. In addition, four members are appointed at-large from each of the four regions. Denius Award nominations due Butler is in his second term on the Council Students excel in UIL activities for sev the award. as a result of the sponsor's leadership over a and served last year as vice chairman. -

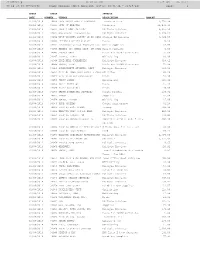

BOARD MEETING CHECK REGISTER (Dates: 02/01/14 - 02/28/14) PAGE: 1

3frdtl01.p ELECTRA ISD 11:37 AM 10/13/14 05.14.10.00.00-010080 BOARD MEETING CHECK REGISTER (Dates: 02/01/14 - 02/28/14) PAGE: 1 CHECK CHECK INVOICE DATE NUMBER VENDOR DESCRIPTION AMOUNT 02/06/2014 34934 ARCHITECTS RABE & PARTNERS Architect Fees 6,750.00 02/06/2014 34935 CITY OF ELECTRA Utilities 11,941.19 02/06/2014 34937 LABATT FOOD SERVICE Multiple Invoices 8,055.50 02/06/2014 34941 OAK FARMS DAIRY-DALLAS Multiple Invoices 5,038.26 02/06/2014 34942 WEST WICHITA COUNTY SP ED COOP Special Ed Services 5,329.58 02/06/2014 34943 PETROLIA ATHLETIC CLUB Meals 74.50 02/06/2014 34944 ADVANTAGE OFFICE PRODUCTS LLC Office Supplies 125.99 02/06/2014 34945 AGENCY 405 TEXAS DEPT. OF PUBL Office Supplies 1.00 02/06/2014 34946 ANDREA GRAY Meals for TASBO Conference 72.00 02/06/2014 34947 BEUTEL, LARRY Officiating 110.00 02/06/2014 34948 BLUE BELL CREAMERIES Multiple Invoices 318.42 02/06/2014 34949 BROCK, LAURA Meals for TASBO Conference 72.00 02/06/2014 34950 BURKBURNETT ATHLETIC DEPT Multiple Invoices 150.00 02/06/2014 34951 CITY OF IOWA PARK WATER & SEWE Utiliites 40.20 02/06/2014 34952 CITY VIEW FFA CONCESSION Meals 55.00 02/06/2014 34953 JERRY COKER Officiating 105.00 02/06/2014 34954 DAIRY QUEEN #2 Meals 125.79 02/06/2014 34955 DAIRY QUEEN #11 Meals 149.80 02/06/2014 34956 DANKA FINANCIAL SERVICES Copier payment 299.32 02/06/2014 34957 DEMCO Supplies 160.64 02/06/2014 34958 DOLAN, KEATON Officiating 115.00 02/06/2014 34959 DYNA SYSTEMS Copier maintenance 62.28 02/06/2014 34960 ELECTRA HIGH SCHOOL Postage 249.00 02/06/2014 34961 ELECTRA HIGH SCHOOL BAND Multiple Invoices 910.00 02/06/2014 34962 ELECTRA LUMBER INC Multiple Invoices 274.99 02/06/2014 34963 ELECTRA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Ambulance Service (10.17.13 - 300.00 11.7.13) 02/06/2014 34964 ELECTRA COMMUNITY SERVICE CLUB S Hogue dues for Dec & Jan 50.00 02/06/2014 34965 ELECTRA FOOD MARKET Food 76.41 02/06/2014 34966 ELECTRA SPECIALTY ADVERTISING Multiple Invoices 1,404.00 02/06/2014 34967 ELECTRA TELEPHONE CO. -

THECB Appendices 2011

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Summer 2011 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Summer 2011 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6147 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities .................................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities ........................................................................ A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges................................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges .................................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies .................................................................... A.5 Health-Related -

Chamber a - Conference 1A Congress Rank Summary

Chamber A - Conference 1A Congress Rank Summary J1 J2 Parli J4 J5 Adj Total 117 Carson Wienecke Lometa High School 1 1 1 2 1 6 6 121 Kali Dennis Texline High School 2 2 2 5 4 15 15 123 Shandi Warren Spur High School 4 3 3 3 5 18 18 120 Brandon Jones Zephyr High School 6 6 11 1 2 24 26 122 Trent Collins Gail: Borden County High School 7 5 4 3 28 28 126 Ryann Stidham Knippa High School 8 7 4 6 7 32 32 117 Camden Wienecke Lometa High School 5 4 6 33 33 119 Halee Sanderson Blackwell High School 5 10 7 6 36 37 115 Clay Lovell Chillicothe High School 3 8 7 36 36 114 Hallie Martin Chireno High School 8 8 8 42 42 124 Garrison Prewozniak Rankin High School 9 45 45 114 Clayton Jones Chireno High School 12 45 48 Tuesday, Jan 12, 2016 06:52PM 2016 UIL State Congress Page 1 Chamber B - Conference 1A Congress Rank Summary J1 J2 Parli J4 J5 Adj Total 118 Kaylee Meador Rising Star High School 1 1 1 6 1 10 10 122 Nathan Souder Gail: Borden County High School 3 2 2 1 2 10 10 125 Bryce Carman Wink High School 3 3 2 4 21 21 115 Jake Knowles Chillicothe High School 2 7 6 3 3 21 21 117 Savannah Phillips Lometa High School 5 6 5 4 5 25 25 116 Sheldon Baty Knox City High School 4 4 6 32 32 124 Zane Nail Rankin High School 7 5 7 8 36 36 119 Shelby Panzer Blackwell High School 4 8 8 38 38 126 Mason Adams Knippa High School 6 10 7 40 41 114 Thad Newman Chireno High School 12 5 41 44 120 Kashtyn Eoff Zephyr High School 8 9 7 42 42 120 Raistlin Meader Zephyr High School 11 8 44 46 Tuesday, Jan 12, 2016 06:52PM 2016 UIL State Congress Page 1 Chamber A - Conference -

Five Years of Enhanced HSTW in Texas

Five Years of Enhanced HSTW in Texas Raising Achievement and Preparing Students for College and Careers Through Dedicated Implementation of the HSTW Key Practices April 2011 Southern Regional Education Board 592 10th St. N.W. Atlanta, GA 30318 (404) 875-9211 www.sreb.org Contents Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................................1 Highlights of Improvements in the Texas Enhanced HSTW and MMGW Networks ..........................................................1 Progress at Schools Having the Most Time in the Network .............................................................................................3 A Closer Look at Accomplishments of HSTW Enhanced Network Schools ......................................................................8 Galena Park High School ....................................................................................................................................................8 South Grand Prairie High School .......................................................................................................................................9 Diboll High School ..........................................................................................................................................................11 Graham High School ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Accredited Secondary Schools in the United States. Bulletin 1916, No. 20

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1916, No. 20 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES SAMUEL PAUL CAPEN SPECIALIST IN HIGHER EDUCATION BUREAU OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 *"■*■ - . ■-■■^■■- ' ' - - - ' _ >ia •;• ••••*•--•. ,-. :~= - c.v - - : , • . v ••. • ‘ ' - . ' ' • - -:;...*- ■ - -v v H m - ;. -- . .' ' " --4' rV'wV'* -w'' A/-O -V ' ^ -v-a 'Ufti _' f - ^3^ ^ DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1916, No. 20 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES BY SAMUEL PAUL CAPEN SPECIALIST IN HIGHER EDUCATION BUREAU OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education, Washington. Sir: Many students apply for admission to higher institutions in other States and sections than those in which they have received their high-school preparation. Many also seek certificates from ex¬ amining and licensing boards, which have no direct means of know¬ ing the standards of the schools from which the applicants come. The demand for this information led the Bureau of Education, first in the spring of 1913 and again in the autumn of 1914, to undertake the collection and preparation of lists of high schools and academies accredited by State universities, approved by State departments of education, or recognized by examining and certifying boards and by certain other agencies. The demand proved to be even greater than had been anticipated. The first edition of the bulletin was soon exhausted. There have be^n many requests from college and uni¬ versity officers for copies of the second edition. Moreover, changes are made in these lists of accredited schools from year to year.