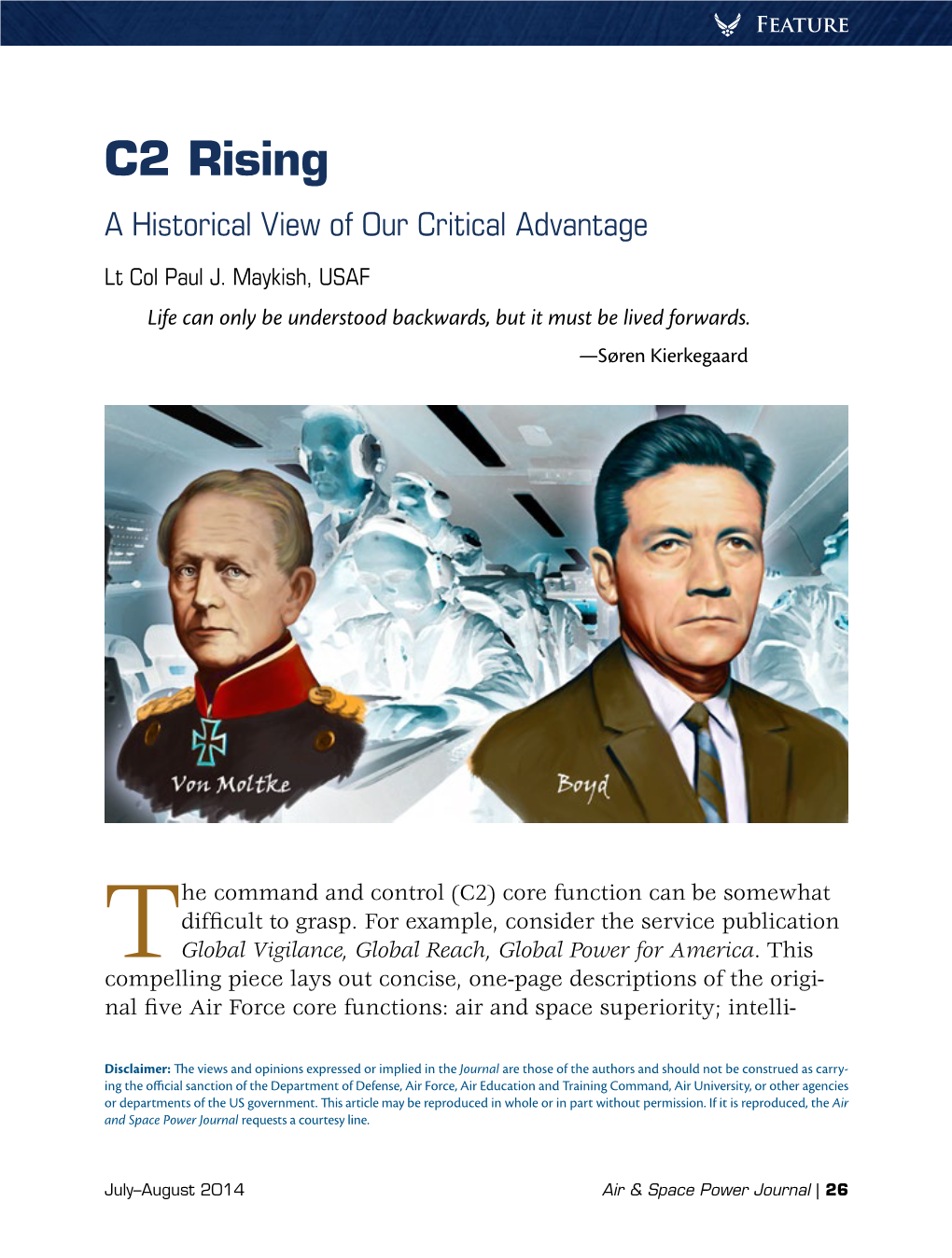

C2 Rising: a Historical View of Our Critical Advantage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE RADAR WAR Forward

THE RADAR WAR by Gerhard Hepcke Translated into English by Hannah Liebmann Forward The backbone of any military operation is the Army. However for an international war, a Navy is essential for the security of the sea and for the resupply of land operations. Both services can only be successful if the Air Force has control over the skies in the areas in which they operate. In the WWI the Air Force had a minor role. Telecommunications was developed during this time and in a few cases it played a decisive role. In WWII radar was able to find and locate the enemy and navigation systems existed that allowed aircraft to operate over friendly and enemy territory without visual aids over long range. This development took place at a breath taking speed from the Ultra High Frequency, UHF to the centimeter wave length. The decisive advantage and superiority for the Air Force or the Navy depended on who had the better radar and UHF technology. 0.0 Aviation Radio and Radar Technology Before World War II From the very beginning radar technology was of great importance for aviation. In spite of this fact, the radar equipment of airplanes before World War II was rather modest compared with the progress achieved during the war. 1.0 Long-Wave to Short-Wave Radiotelegraphy In the beginning, when communication took place only via telegraphy, long- and short-wave transmitting and receiving radios were used. 2.0 VHF Radiotelephony Later VHF radios were added, which made communication without trained radio operators possible. 3.0 On-Board Direction Finding A loop antenna served as a navigational aid for airplanes. -

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Ops Block Battle of Britain: Ops Block

Large print guide BATTLE OF BRITAIN Ops Block Battle of Britain: Ops Block This Operations Block (Ops Block) was the most important building on the airfield during the Battle of Britain in 1940. From here, Duxford’s fighter squadrons were directed into battle against the Luftwaffe. Inside, you will meet the people who worked in these rooms and helped to win the battle. Begin your visit in the cinema. Step into the cinema to watch a short film about the Battle of Britain. Duration: approximately 4 minutes DUXFORD ROOM Duxford’s Role The Battle of Britain was the first time that the Second World War was experienced by the British population. During the battle, Duxford supported the defence of London. Several squadrons flew out of this airfield. They were part of Fighter Command, which was responsible for defending Britain from the air. To coordinate defence, the Royal Air Force (RAF) divided Britain into geographical ‘groups’, subdivided into ‘sectors.’ Each sector had an airfield known as a ‘sector station’ with an Operations Room (Ops Room) that controlled its aircraft. Information about the location and number of enemy aircraft was communicated directly to each Ops Room. This innovative system became known as the Dowding System, named after its creator, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command. The Dowding System’s success was vital to winning the Battle of Britain. Fighter Command Group Layout August 1940 Duxford was located within ‘G’ sector, which was part of 12 Group. This group was primarily responsible for defending the industrial Midlands and the north of England, but also assisted with the defence of the southeast as required. -

571 Write Up.Pdf

This paper comprises a brief history of the origins and early development of radar meteorology. Therefore, it will cover the time period from a few years before World War II through about the 1970s. The earliest developments of radar meteorology occurred in England, the United States, and Canada. Among these three nations, however, most of the first discoveries and developments were made in England. With the exception of a few minor details, it is there where the story begins. Even as early as 1900, Nicola Tesla wrote of the potential for using waves of a frequency from the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum to detect distant objects. Then, on 11 December 1924, E. V. Appleton and M.A.F. Barnett, two Englishmen, used a radio technique to determine the height of the ionosphere using continuous wave (CW) radio energy. This was the first recorded measurement of the height of the ionosphere using such a method, and it got Appleton a Nobel Prize. However, it was Merle A. Tuve and Gregory Breit (the former of Johns Hopkins University, the latter of the Carnegie Institution), both Americans, who six months later – in July 1925 – did the same thing using pulsed radio energy. This was a simpler and more direct way of doing it. As the 1930s rolled on, the British sensed that the next world war was coming. They also knew they would be forced to defend themselves against the German onslaught. Knowing they would be outmanned and outgunned, they began to search for solutions of a technological variety. This is where Robert Alexander Watson Watt – a Scottish physicist and then superintendent of the Radio Department at the National Physical Laboratory in England – came into the story. -

Spring 2017 Some Reflections on the History of Radar from Its Invention

newsletter OF THE James Clerk Maxwell Foundation ISSN 205 8-7503 (Print) Issue No.8 Spring 2017 ISSN 205 8-7511 (Online) Some Re flections on the History of Radar from its Invention up to the Second World War By Professor Hugh Griffiths , DSc(Eng), FIET, FIEEE, FREng, University College, London, Royal Academy of Engineering Chair of Radio Frequency Sensors Electromagnetic Waves – Maxwell and Hertz In 1927, in France, Pierre David had observed similar effects and, in 1930, had conducted further trials, leading to a deployed In his famous 1865 paper ‘ A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic forward-scatter radar system to protect the naval ports of Brest, Field’ Maxwell derived theoretically his famous equations of Cherbourg, Toulon and Bizerte (Algeria). electromagnetism which showed that these equations implied that electromagnetic disturbances travelled as waves at finite speed. In 1935, in the UK, Robert Watson-Watt had a claim to be From the fact that the speed of these waves was equal (to within ‘the father of radar’ on the basis of the Daventry Experiment experimental error) to the known velocity of light, Maxwell (described later in this article) and his development of a radar detection system (Chain Home) for the R.A.F. in World War II. concluded with the immortal words: “This velocity is so nearly that of light that it seems we have strong reason But, to the author, the priority for the invention of radar should go to conclude that light itself (including radiant heat and other radiations if to a German, Christian Hülsmeyer, a young engineer who in 1904 built and demonstrated a device to detect ships. -

Extracts From…

Extracts from…. The VMARS News Sheet Issue 147 June 2015 British Post War Air Defence Radar been largely cobbled together, developed, At 07:00 On 29th August 1949, the Steppes of modified and added to as the demands of war northeast Kazakhstan were shaken by a huge dictated, but which still formed the bedrock of explosion as the USSR detonated a nuclear test bomb British air defence capability in 1949. A report was as the culmination of Operation First Lightning, the commissioned, in which it identified weaknesses first of the 456 Soviet nuclear tests destined to take in detecting aircraft at high altitude, geographical place in that region over the following 40 years. Since areas that were inadequately covered, poor IFF July 1945, when the first nuclear bomb test was systems, an outdated communications and carried out in New Mexico, the USA had been the reporting network and obsolete equipment with only country to possess a nuclear capability and the poor reliability, leaving Britain vulnerable to a news that the USSR was now similarly equipped, Soviet nuclear attack. Even so, the possibility of stunned America. Relations between the USSR and high altitude Soviet TU-4s carrying 20 megaton Western governments had deteriorated rapidly nuclear bombs reaching British shores undetected following the end of the war with Germany and in a was insufficient to motivate the government humiliating defeat of Joseph Stalin’s attempts to Treasury department to loosen their purse strings isolate Berlin from the western Allied nations of sufficiently for anything more urgent than a 10 Britain, USA and France, the Russian blockade of year programme of renewal. -

The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

United States Cryptologic History The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park Special series | Volume 12 | 2016 Center for Cryptologic History David J. Sherman is Associate Director for Policy and Records at the National Security Agency. A graduate of Duke University, he holds a doctorate in Slavic Studies from Cornell University, where he taught for three years. He also is a graduate of the CAPSTONE General/Flag Officer Course at the National Defense University, the Intelligence Community Senior Leadership Program, and the Alexander S. Pushkin Institute of the Russian Language in Moscow. He has served as Associate Dean for Academic Programs at the National War College and while there taught courses on strategy, inter- national relations, and intelligence. Among his other government assignments include ones as NSA’s representative to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council, and on the staff of the National Economic Council. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (Top) Navy Department building, with Washington Monument in center distance, 1918 or 1919; (bottom) Bletchley Park mansion, headquarters of UK codebreaking, 1939 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park David Sherman National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History 2016 Second Printing Contents Foreword ................................................................................ -

Shoreham's Radar Station-Bookv2

The Story of RAF Truleigh Hill by Roy Taylor Copyright Aug. 2020 Page 1 of 107 Contents Introduction……………………………………………. 1 1. Radar Development………………………………... 3 2. Wartime…………………………………………….. 4 3. Poling………………………………………………. 20 4. GEE Navigational Aid……………………..............26 5. ROTOR Period – Technical Site………………….33 6. Stoney Lane Domestic Site……………………….. 43 7. Sport………………………………………………. .52 8. Commanding Officers…………………….…….. 57 9. Finding the Veterans…………………………….. .61 10. Local Involvement………………………………. 74 11. Later Developments……………………………... 77 Appendix 1 - Roll Call………………………… …… 81 Gallery…………………………............ 86 Appendix 2 – Other Sussex RAF Radar Stations….. 93 Appendix 3 – Further Reading……………………… 94 Appendix 4 – Technical Notes (CHEL) 95 Acknowledgements………………………………… 98 The Story of RAF Truleigh Hill by Roy Taylor Copyright Aug. 2020 Page 2 of 107 Shoreham’s Radar Station The Story of RAF Truleigh Hill Introduction The Story of RAF Truleigh Hill by Roy Taylor Copyright Aug. 2020 Page 3 of 107 It is over fifty years since I first set foot in Shoreham, as a 19-year-old radar operator at RAF Truleigh Hill. I served the final 15months of my compulsory period of National Service at this, the last of my six postings. On demob, I stayed in the area and have been here ever since. I have kept in contact with four of my former colleagues. Photos and memories come out for an airing every so often, but it is only in the last few years, however, that I have started to think seriously about the history of RAF Truleigh Hill. The radar operation started in 1940, just before The Battle of Britain, and continued in several different formats until closure in 1958. -

{DOWNLOAD} Fighter: the True Story of the Battle of Britain

FIGHTER: THE TRUE STORY OF THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Len Deighton | 360 pages | 27 Feb 2014 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007531189 | English | London, United Kingdom Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain - Len Deighton - Google Libri The German "Blitzkrieg" moved swiftly to the west and the south, splitting the British and French defenders, trapping the British army at Dunkirk and forcing its evacuation from continental Europe. The British now stood alone, awaiting Hitler's inevitable attempt to invade and conquer their island. Great Britain was in trouble. The soldiers rescued from Dunkirk were exhausted by their ordeal. Worse, most of their heavy armaments lay abandoned and rusting on the French beaches. After a short rest, the Germans began air attacks in early summer designed to seize mastery of the skies over England in preparation for invasion. All that stood between the British and defeat was a small force of RAF pilots outnumbered in the air by four to one. Day after day the Germans sent armadas of bombers and fighters over England hoping to lure the RAF into battle and annihilate the defenders. Day after day the RAF scrambled their pilots into the sky to do battle often three, four or five times a day. Their words bring the events they had witnessed just hours before to life in a way no modern commentary could. The Battle of Britain Combat Archive brings the colour back with dozens of specially commissioned artworks and profiles of the aircraft. Artist Mark Postlethwaite has designed a full colour format to make each page and table easy to understand. -

Identifying the Effects of Space Acquisition Timelines on Space Deterrence and Conflict Outcomes

Dissertation A Need for Speed? Identifying the Effects of Space Acquisition Timelines on Space Deterrence and Conflict Outcomes Benjamin Goirigolzarri This document was submitted as a dissertation in September 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. The faculty committee that supervised and approved the dissertation consisted of William Shelton (Chair), Bonnie Triezenberg, and Jonathan Wong. PARDEE RAND GRADUATE SCHOOL For more information on this publication, visit http://www.rand.org/pubs/rgs_dissertations/RGSD432.html Published 2019 by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. R® is a registered trademark Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Abstract Department of Defense leadership have asserted that slow space acquisition timelines may threaten American space superiority, but the link between acquisition timelines and space conflict has not been rigorously investigated in prior research. -

View of the British Way in Warfare, by Captain B

“The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Katie Lynn Brown August 2011 © 2011 Katie Lynn Brown. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 by KATIE LYNN BROWN has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BROWN, KATIE LYNN, M.A., August 2011, History “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst The historiography of British grand strategy in the interwar years overlooks the importance air power had in determining Britain’s interwar strategy. Rather than acknowledging the newly developed third dimension of warfare, most historians attempt to place air power in the traditional debate between a Continental commitment and a strong navy. By examining the development of the Royal Air Force in the interwar years, this thesis will show that air power was extremely influential in developing Britain’s grand strategy. Moreover, this thesis will study the Royal Air Force’s reliance on strategic bombing to consider any legal or moral issues. Finally, this thesis will explore British air defenses in the 1930s as well as the first major air battle in World War II, the Battle of Britain, to see if the Royal Air Force’s almost uncompromising faith in strategic bombing was warranted. -

Appendix 1: Three Level Hierarchy Monument Classification System

New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II April 2013 Appendix 1: Three Level Hierarchy Monument Classification System Top Term Broad Term Monument Type ADMIRALTY SIGNAL ESTABLISHMENT ADMIRALTY SIGNAL STATION AIRCRAFT CRASH SITE AIRSHIP STATION AUXILIARY FIRE STATION AUXILIARY HOSPITAL BOMB CRATER BOMBING RANGE MARKER AIR DEFENCE SITE AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY COMMAND POST AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY ANTI AIRCRAFT GUN EMPLACEMENT AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY BATTERY OBSERVATION POST AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY HEAVY ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY LIGHT ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY Z BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT GUN TOWER AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS ROOM AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON CENTRE AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON GAS DEPOT Maritime Archaeology Ltd MA Ltd 1832 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk Page 1 of 79 New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II April 2013 Top Term Broad Term Monument Type AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON HANGAR AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON MOORING AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SHELTER AIR DEFENCE SITE SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY BATTERY OBSERVATION