OAK CHAIRS from ULSTER Fionnuala Carragher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GRANT AVAILABLE FRO$ Mid-Hudson Migrant

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 248 096 RC 014 944 TITLE Construction/Communication-Eg Media: B5. CHOICE: I, Challenging Options in Career Education. ,,INSTITUTION Mid-Hudson Migrant Education Center, New Paltz, NY.; Putnam and Northern WestChester Counties Board of Cooperative Educational Services,-Yorktown Heights, N.Y.; Ulster County Board of Cooperative Educational Service' /ew SPONS AGENCY Employee.. and Training Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C. Office of Youth Programs.'; Office of Elementary ind Secondary Education (ED), Washington; DC. Migrant Education Programs. PUB DATE 83 GRANT 28-84-0023 NOTE 454p.; For relates documents, see RC 014 933-946. Best copy.imailable. To avoid repetition ofidentical') pages, ceparate teacher logs, student logs, pre/post tests, and activity folders have been merged to create a single document. AVAILABLE FRO$CHOICE, P. 0. Box 250, New Paltz, NY 12561 (Teacher Log, $5.00 plus shipping; Student Log, $2.50 plus shipping; Student Activities -- laminated folders--$30.00 plus shipping)'. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Career Education; Cognitive Development; *Communications; *Construction Industry; Educational Games; Elementary Education; *Grade 4; Instructional Langukage-Arts; Learning Activities; Mass Media; Mathematics Skills; *Migrant Education; Occupational Clusters; *Occupational Information; Skill Development; Teaching Guides; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *CHOICE (Career Education Curriculum) # ABSTRACT The documents aggregated here comprise the fourth grade unit of a career education curriculum for migrant students. The unit focuses on the tools.ind tasks of workers in 11 jobs in the construction, communication, and media occupational clusters: heavy equipment operator, architect, mason, carpenter, plumber, electrician, telephone line worker, announcer, photographer, journalist, and performer. -

The Complete Illustrated Guide to Shaping Wood / Lonnie Bird

The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood LONNIE BIRD ➤ Squares, Circles, and Ellipses ➤ Edge Treatments and Moldings ➤ Coves, Reeds, and Flutes ➤ Bent and Laminated Curves ➤ Turned and Carved Shapes The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A(D) The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood LONNIE B IRD t TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A Magenta(D) Text © 2001 by Lonnie Bird Photographs © 2001 by Lonnie Bird Illustrations © 2001 by The Taunton Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Pp The Taunton Press, Inc., 63 South Main Street, PO Box 5506, Newtown, CT 06470-5506 e-mail: [email protected] DESIGN: Lori Wendin LAYOU T: Suzi Yannes ILLUSTRATOR: Mario Ferro PHOTOGRAPHER: Lonnie Bird LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA: Bird, Lonnie. The complete illustrated guide to shaping wood / Lonnie Bird. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-1-56158-400-0 ISBN-10: 1-56158-400-2 1. Woodwork. I. Title. TT180 .B57 2001 TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A Magenta(D) 684’.08--dc21 2001027430 Printed in Thailand 1098765 About Your Safety: Working with wood is inherently dangerous. Using hand or power tools improperly or ignoring safety practices can lead to permanent injury or even death. -

Moulding & Millwork Guide

#214 $7.50 MOULDING & MILLWORK GUIDE BUILDING MATERIALS DISTRIBUTION For 1,000 more moulding profiles visit our website: www.taguelumber.com Kennett Square | Malvern | Media | Philadelphia | Phoenixville For over 100 years... Since 1908 Tague Lumber has been providing professional builders and remodelers with superior: lumber, building materials, millwork, and architectural products. We pride ourselves on providing professional service, fair prices, and quality products to all our customers. In addition, Tague offers prompt, on-site delivery from our distinctive fleet of red trucks including: 6-story boom trucks, moffett fork lifts, flatbed trucks, curtain side box trucks, standard box trucks, and service vans that can deliver what you want, exactly where you want it. Our Moulding Guide continues to be a valued source of reference and inspiration to all our clients. Now, we proudly present the revised edition of our Moulding Guide with expanded profile categories and many new moulding selections which are available in a variety of wood species, as well as MDF and PVC. The easy-to-use index allows you to search for mouldings by category or by individual profile number. In addition to the hundreds of profiles in this book, Tague Lumber has over 1,000 more moulding profiles available on our website, and in excess of 2,000 knives in our library. Our profiles are also available for download in DWG and DXF formats on our website. Best of all, our Custom Mill Shop allows us to make this promise—if we don’t already have the moulding profile you need—we’ll be happy to make it for you. -

A Description of 19Th-Century American Gilded Picture Frames

Figure 1. Plate 9 from Benjamin, A. (1827). The American Builder’s Companion. “A, cavetto, or hollow; B, cavetto and astragal; C, ovolo and fillet; D, ovolo and astragal; E, cymareversa, or ogee; F, cymareversa and bead; G, astragal; H, bead; I, cimarecta; K, L, and M, are scoties of different projections and curves; N, O, P, are quirk ogees.” 2006 WAG Postprints—Providence, Rhode Island A Description of 19th-century American Gilded Picture Frames and an Outline of Their Modern Use and Conservation Hugh Glover, Conservator of Furniture and Wood Objects, Williamstown Art Conservation Center ABSTRacT Picture frames are a functional component of most art collections and they are subject to wear and tear as they fulfill their housing function for paintings. Damage to picture frames can occur during exhibitions, storage, and travel, and is caused by handling, hanging processes, adverse environments, neglect, and irreversible restorations. Picture frames are maintained by a variety of preservation specialists, and despite their ubiq- uity they have not become the domain of any one conservation discipline, and there is scant literature devoted to their preservation interests. This paper will focus on the analysis of 19th century American gilded picture frames, as well as preventive care, modern modifications, and restoration/conservation treatments. The talk is derived from the cumulative experience in treating frames at the Williamstown Art Conserva- tion Laboratory (WACC). The paper will address frame nomenclature and the development of popular styles and con- structions of the 19th century. It will outline ornament forms and materials, and give an overview of period gilding techniques. -

Architectural Terminology

Architectural Terminology Compiled by By Trail End State Historic Site Superintendent Cynde Georgen; for The Western Alliance of Historic Structures & Properties, 1998 So what is a quoin anyway … other than a great word to have in your head when playing Scrabble®? Or how about a rincleau? A belvedere? A radiating voussoir? If these questions leave you scratching your head in wonder and confusion, you’re not alone! Few people outside the confines of an architect’s office have a working knowledge of architectural terminology. For you, however, that’s about to change! After studying the following glossary, you’ll be able to amaze your friends as you walk through the streets of your town pointing out lancets, porticos, corbels and campaniles. NOTE: The definitions of some terms use words which themselves require definition. Such words are italicized in the definition. Photograph, balustrade, undated (By the Author) Acanthus Leaf - Motif in classical architecture found on Corinthian columns Aedicule - A pedimented entablature with columns used to frame a window or niche Arcade - Series of round arches supported by columns or posts Architrave - The lowest part of a classical entablature running from column to column Ashlar - Squared building stone laid in parallel courses Astragal - Molding with a semicircular profile Astylar - Facade without columns or pilasters Balconet - False balcony outside a window Baluster - The post supporting a handrail Balustrade - Railing at a stairway, porch or roof Architectural Terminology - 1 - www.trailend.org -

PWM Style Book Jan 2014.Pdf

Style Book Revised: January 2014 PW Style Book Revised: Jan 2014 Numbers, Measurements • #400-grit (adj) • 30 years adze (n): a primitive tool for surfacing lumber and Callouts • #400 grit (n) • #0000 steel wool • #1,000 grit stone • 1-pound cut, 2-pound cut etc. aftermarket (n): the market for parts, accessories and repairs • 40-tooth (adj) (for shellac) • thickness x width x length of a product; also, a secondary • On anything dimensional, • $2,800 (not $2800) • 1 horsepower; 1 hp (1-hp market for a product after the use numerals and birds’ feet, router); spell out ‘horsepower’ primary market; an aftermarket • 2" scale even if it’s an approximation on first reference, then can use fence for a table saw, for example • 32" x 48" ‘hp’ abbreviation (this departs from AP style) AIA (abbreviation): American • 4' x 7' 1/4"-20 (machine screw thread; • 4/4 lumber (reads as “four- Institute of Architects • 2x4; 2x4s (Name for quarter lumber”; refers to rough- 1/4" is diameter, 20 is threads per air-conditioner (n); construction-grade lumber, cut lumber measured by quarters inch) air-conditioning (A/C) (n); usually pine, generally used for or an inch; do not set as stacked • 70°F (no space; don’t spell out air-conditioned (adj) wall studs; is not really 2" by 4", fractions) on first ref.) air-dry (v); air-dried (adj): a but an estimate of the size used • mid-1800s • 3D (departure from AP) commonly; do not include inch method of seasoning lumber •30mm, 25 cm marks) which permits the sawn wood, • model 41293 which is usually protected from • 90° -

Report on Forest Research 1996

Forestry Commission REPORT ON FOREST RESEARCH 1996 mm Forestry Commission ARCHIVE REPORT ON FOREST RESEARCH For the year ended March 1996 Forestry Commission, Edinburgh Advisory Committee on Forest Research Chairm an PROFESSOR H. G. MILLER Department of Forestry, University of Aberdeen, St. Machar Drive, Aberdeen AB9 2UU. Secretary Dr D. A. ROOK Forestry Commission, Northern Research Station. Members PROFESSOR W. B. BANKS University of Wales, School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW. DR A. F. BRAVERY Timber Division, Building Research Establishment, Garston, Watford WD2 7JR. PROFESSOR J. P. BLAKEMAN Plant Pathology Research Division, Agriculture and Food Science Centre, Newforge Lane, Belfast BT9 5PB. PROFESSOR R. M. CORMACK Statistics Division, Department of Mathematical Sciences, North Haugh, St. Andrews, Fife KY16 9SS. DR A. R. GRIFFIN Non Traditional Division, Shell International, NTBF/6, Shell Centre, London SE1 7NA PROFESSOR B. R. KERRY Entomology and Nematology Department, Rothamsted Experimental Station, Harpenden, Herts AL5 2JQ^ D R P. S. SAVILL © Crown Copyright 1996 Oxford Forestry Institute, South Parks Road, Oxford 0X1 3RB. ISBN 0 85538 344 5 FDC 945.4: (410) PROFESSOR M. B. USHER The abbreviated title o f this Report is Scottish Natural Heritage, 2 Anderson Place, Rep. Forest Res., Edin. 1996 Edinburgh EH6 5NP. Contents Advisory Committee on Forest Research ii Research Division organisation iv Introduction 1 Farm woodland research in the lowlands of Britain 3 Developing cost-effective methods for successful restocking 11 Disease and pest problems 15 New horizons in Dutch elm disease control 20 Ecological site classification 29 Modelling the effects of global change on European forests 34 Yield model predictions of tree survival in unthinned Sitka spruce 38 Squirrel population and habitat management 40 Application of the freshwater critical loads approach to forestry 43 Genetic diversity of native black poplar 48 Some examples of computing and statistical techniques used in forestry research 51 Appendices 1. -

Cutting Tools

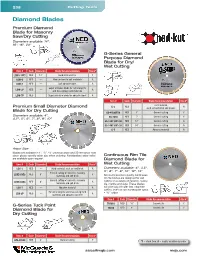

238 Cutting Tools Diamond Blades Premium Diamond Blade for Masonry Saw/Dry Cutting Diameters available: 14", 16", 18", 20" G-Series General Purpose Diamond Blade for Dry/ Wet Cutting Item # Code Diameter Blade Recommendation Stock* LDM3-14X1 NED 14" Hard brick and tile Y LDM-5 NED — Medium hard to soft materials A LDM-7 NED — Soft abrasive block A Super premium blade for extra long life NED — A LDM-2P and free-cutting hard materials LDM-7P NED — Super premium blade for abrasive block A Item # Code Diameter Blade Recommendation Stock* Hard material, NED — A Premium Small Diameter Diamond G-3 such as hard brick and pavers Blade for Dry Cutting G5-4X080X78 NED 4" General cutting Y Diameters available: 4", G5-7X58 NED 7" General cutting Y 4.5", 5", 6", 7", 8", 9", 10" G5-12X110X1/20 NED 12" General cutting A G5-14X110X1/20 NED 14" General cutting A G-7 NED — Abrasive material A Arbor Size Blades are available in 1", 7⁄8", 5⁄8" universal arbor and 20 mm arbor hole sizes; please specify arbor size when ordering. Nonstandard arbor holes Continuous Rim Tile are available upon request. Diamond Blade for Item # Code Diameter Blade Recommendation Stock* Wet Cutting LDX-3 NED — Hard material, such as hard brick A Diameters available: 4", 4.5", 5", 6", 7", 8", 10", 12", 14" General cutting of concrete, masonry NED 6" Y LDX5-6X58 materials and soft brick Ned-kut’s premium quality continuous rim tile blades are designed for wet General cutting of concrete, masonry LDX5-8X58 NED 8" A cutting on a variety of ceramic, quarry, materials and soft brick tile, marble and slate. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, SEVIN BRAND RP2 CARBARYL

•. ." . • r····'9 SEVINe brand RPZ , td~ .}..O Carbaryl Insecticide fl"l'} Home and Garden Insecticide ?-b~'? 3{j- ACTIVE IN"REOIENTS: Carbaryl (1-r.J,hthyl N-methylcarbamate) .....•.. INERT INGREDIENTS:. 77 .5~ by wt. This product contains the toxic inert ingredient formaldehyde. (Contains 2 Pounds Carbaryl Per Gallon) E.P.A. Reg. No. 264-334 E.P.A. Est. No. 264-MO-02 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION See page 2 for additional PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS. IN CASE OF EMERGENCY TELEPHONE (24 HOURS A DAY) IN THE U.S.A. 1-800-UCC-HELP FOR GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION CALL 1-800-334-9745 NET CONTENTS: ____ Made in U.S.A. " CONlON CARBIDE AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS COMPANY, INC. P. p. Box 12014, T. W. Alexander Drive Research Trfangle Park, NC 27709 ' SEVIN~" fs a regfstered trademark of Unfon'Carbide Agrfcultural Products • •• ••••••• • • Ccrn~any. Inc. for carbaryl insectfcfdes. • • • • • •••• • • •••••• • • •• ••••••• • ••••• • • ... ... • • • 0 • • • 0 ... APe For'll No. __ • ·· . · ·, • • • • • • · .. " . ... 0 · • • • 0~33X/MASTER/03-18-8S -1- .; I I • . PRECAijfIONARY STATEMENTS . '~'. - -. CAUTION HAZARDS TO HUMANS AND DOMESTIC ANIMALS HAY BE HARMFUL IF SWALLOWED. Avoid breathing of spray mist. Do not take internally. Avoid contact with eyes, skin or clothing. Wear regular long-sleeved work clothing. Change to clean clothing daily. Wash hands and face before eating. Wash thoroughly after handling. STATEMENT OF PRACTICAL TREATMENT IF SWALLOWED; Induce vomiting and seek medical attention immediately. IF IN EYES OR ON SKIN; Flush eyes with plenty of water. Wash skin thoroughly with soap and water. NOTE TO PHYSICIAN Carbaryl is a moderate, reversible cholinesterase inhibitor. Atropine is antidotal. -

Fine Woodworking 2007 Building Furniture

FINE WOODWORKING’S BUILDING FURNITURE 2007 THE BEST OF furniturebuilding How to make: Bookcases • Tables • Chairs Cabinets • Chests • Bureaus Beds • Sideboards $8.99/Canada $9.99 A Taunton Publication Display until Oct. 31, 2007 www.finewoodworking.com FWSIP08BF_FCf.indd 1 6/14/07 5:16:41 PM FW192aADp2.indd 6/5/07 2:18:20 PM pg 2 - (Cyan)(Magenta)(Yellow)(BlacK) FW192aADp3.indd 6/5/07 2:19:37 PM pg 3 - (Cyan)(Magenta)(Yellow)(BlacK) THE LEFT-TILT CONTRACTOR’S SAW. PERFECTED. It should come as no surprise that DELTA® took the time to introduce left-tilt Contractor’s Saws® the right way. After all, DELTA invented the Contractor’s Saw category. And once you try a DELTA, there’s no going back. Besides a left-tilt blade and powerful 1-1/2 HP motor, you also have a choice of three fence systems including a Biesemeyer® or DELTA® UNIFENCE.® You even get maximum mobility with a newly designed base. Plus, its new collection tray captures 80 - 90% of the dust. So find perfection. Visit deltamachinery.com/contractor for more details, or to join our DELTA Owners Group. LEFT-TILT BLADE INTEGRATED DUST PORT MOBILE BASE THE BESTw OF furniturebuilding contents Bookshelves Tables Beds 18 Three Bookcases 30 Table Design 48 Anatomy of a Bed From simple to elegant, A well-proportioned table Construction details that work three approaches to building offers both comfort and style with almost any design a home for your books BY GRAHAM BLACKBURN BY JEFF MILLER BY PHILIP C. LOWE 34 Strong Joints Chairs 24 Sturdy Shelves Build sturdier tables How to build shelves -

MAY the (Mentoring) FORCE BE with YOU Introduction

MAY THE (Mentoring) FORCE BE WITH YOU by Jeff Clunie The purpose of this article is to share with Guild members my recent experience of going through a woodworking mentoring program with another more knowledgeable and experienced member of the Guild who was willing to share his knowledge with others. As a result of going through this mentoring experience, my woodworking skills were significantly enhanced, although they were relatively minimal to begin with, and my appreciation for what is entailed to make a good piece of furniture has increased. Introduction In January 2015, Don Michael and Jim Russell told me that they planned on building a “Portsmouth Table” and asked if I wanted to participate in the effort. I looked at the pictures and drawings they had of a Portsmouth Table and I was not favorably impressed with what I saw as it appeared rather ostentatious. The table has a top which is approximately 17 inches square, it is 29 inches tall, has a single drawer, and one shelf. It is the embellishments, however, that are eye popping. This table includes all of the following: stringing; bookmatch veneer top and shelf; side banding around the sides of the top ; scallop skirts around the sides of the shelf; sawtooth banding around the base of the scallop skirts; veneer inlays on the tops of the legs; stringing around the veneer inlays on the legs; cross banding veneer on the front of the drawer; an elliptical veneer inlay on the front of the drawer; cock beading around the edges of the drawer; turned legs that included horizontal beading and tapered feet; and vertical reeding on the bottom half of the leg. -

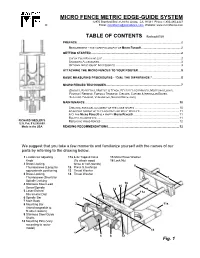

Micro Fence Metric Edge-Guide System

MICRO FENCE METRIC EDGE-GUIDE SYSTEM 12970 Branford Street Unit M, Arleta, CA 91331 Phone 1-800-480-6427 ® Email: [email protected] Website: www.microfence.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Revised 07/03 PREFACE .............................................................................................................................. 2 MEASUREMENT – THE CORE PHILOSOPHY OF MICRO FENCE® ................................................ 2 GETTING STARTED ............................................................................................................. 2 CHECK YOUR PACKING LIST ............................................................................................... 2 STANDARD ACCESSORIES .................................................................................................. 3 OPTIONAL EDGE-GUIDE ACCESSORIES ............................................................................... 3 ATTACHING THE MICRO FENCE® TO YOUR ROUTER .................................................... 5 BASIC MEASURING PROCEDURES - “DIAL THE DIFFERENCE.” ................................... 5 MICRO FENCE® TECHNIQUES ........................................................................................... 7 (DADOES, RABBETING, MORTISE & TENON, RECESSES FOR HINGES, MORTISING LOCKS, FLUTING / REEDING, FORMICA TRIMMING, CIRCLES, CURVED & IRREGULAR EDGES, SLOTTING / VEINING, V-GROOVES, SLIDING DOVETAILS) MAINTENANCE .................................................................................................................. 10 CHECKING