Copy 2 of DOC587

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil Palm Plantations in Forest Landscapes: Impacts, Aspirations and Ways Forward in Uganda

Oil palm plantations in forest landscapes: impacts, aspirations and ways forward in Uganda Richard Ssemmanda and Michael Opige (eds.) This publication has been produced under the framework of the Green Livelihoods Alliance - Millieudefensie, IUCN-NL and Tropenbos International - funded under the ‘Dialogue and Dissent’ strategic partnership with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. The opinions and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of Tropenbos International or its partners. Suggested citation: Ssemmanda R. and Opige M.O. (eds.). 2018. Oil palm plantations in forest landscapes: impacts, aspirations and ways forward in Uganda. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Tropenbos International ISBN: 978-90-5113-139-0 Additional editing by: Nick Pasiecznik and Hans Vellema Layout by: Juanita Franco Photos: Hans Vellema (Tropenbos International) Tropenbos International P.O. Box 232 6700 AE Wageningen The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tropenbos.org Contents Overview Paradise lost, or found? The introduction of oil palm to Uganda’s tropical forest 5 islands in Lake Victoria – a review of experiences and proposed next steps Richard Ssemmanda, Michael Opige, Nick Pasiecznik & Hans Vellema Background reviews Land use changes (1990-2015) in Kalangala and 14 Buvuma districts, southern Uganda Grace Nangendo Environmental impacts of oil palm plantations in Kalangala 22 Mary Namaganda Impacts of oil palm on forest products and -

Chapter Three

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. 2nd of 3 files Chapters 3 to 8 (page 62 to 265) of WALKING THE RIFT: ALFRED ROBERT TUCKER IN EAST AFRICA IDEALISM AND IMPERIALISM 1890 – 1911 by JOAN PLUBELL MATTIA A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham 2007 62 CHAPTER THREE THE MARRIAGE QUESTION Arriving in Mombasa harbour on May 14, 1890, sick and weak from unsanitary food preparation on board the “Ethiopian,” Alfred Tucker, third bishop of the immense territory comprising the Diocese of Eastern Equatorial Africa (1890-1899), was greeted with the words, “Cotter dead” by Mr. Bailey, the missionary assigned to meet him. Tucker’s immediate response to this news of the loss of one of the Mombasa missionaries was to acknowledge “the intense anguish of my mind when with such tidings ringing in my ears and feeling physically weak and ill I set foot for the first time on the shores of Africa.”1 It would be far from the last death among the Church Missionary Society personnel in his twenty-one year episcopacy in East Africa but, with the history of death in the East African endeavour and the uncertainty of his own well-being so close at hand, the gravity of the greeting elicited the anxiety laden response recorded above. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Your Lake Victoria Experience Starts Here!

Menu Noted as one of the "World’s Best Secret Islands" by the BBC's travel and culture documentary "Lonely Planet", the Ssese Islands on Lake Victoria comprise of 84 small islands, the second largest of which is Bukasa. With very few inhabitants, Bukasa Island boasts many natural forests, grasslands, beaches, a natural waterfall with plunge pool and a unique tranquility surrounded by beautiful and interesting ora and fauna. The Serendipity Holiday Resort Welcomes You To Lake Victoria Set in over 100 acres of privately own land the Serendipity Holiday Resort is the perfect getaway for peace, tranquility, luxury and escapism. However, we also oer a whole range of activities from a variety of water sports through to nature walks, shing and safari excursions. Simply put, we cater for your requirements... Your Lake Victoria Experience Starts Here! Accommodation Island Beauty With a range of accommodation from luxury camping Breathtaking tranquility awaits you in the surrounding pods to exquisite African style self contained beauty and nature of Bukasa Island's beaches and apartments. Beach front or woodland locations and all forests. Flowers, plants, scenery and wildlife are all distributed to ensure privacy without compromising great natural attractions with a variety of birds and the beautiful views and surroundings... Read more... home to the Vervet Monkeys... Read more... Facilities Activities Menu All accommodation suites have a private shower (or Enjoy Bukasa Island nature walks, guided trails, quad bath in some cases), a TV with pre-loaded movies, trekking, Ssese Island excursions, jet skiing, banana series and music, plus a mini fridge, tea making boat rides, freedom yer exhilaration, the Seabreacher facilities and WiFi. -

BANS, TESTS and ALCHEMY: FOOD SAFETY STANDARDS and the UGANDAN FISH EXPORT INDUSTRY Stefano Ponte DIIS Working Paper No 2005/19

DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES STRANDGADE 56 • 1401 COPENHAGEN K • DENMARK TEL +45 32 69 87 87 • [email protected] • www.diis.dk BANS, TESTS AND ALCHEMY: FOOD SAFETY STANDARDS AND THE UGANDAN FISH EXPORT INDUSTRY Stefano Ponte DIIS Working Paper no 2005/19 © Copenhagen 2005 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mails: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi as ISBN: 87-7605-104-8 Price: DKK 25,00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Stefano Ponte, Ph.D., is Senior Researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen. He can be reached at [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 2. The international regulatory framework governing exports of fish from Lake Victoria .............................................................................................................................................5 2.1 Main agreements and tariff barriers ...............................................................................................5 2.2 Non-tariff barriers ............................................................................................................................6 3. Uganda fisheries on Lake Victoria: a profile ...........................................................................9 -

Environmental Impacts of Oil Palm Plantations in Kalangala(PDF)

Environmental impacts of oil palm plantations in Kalangala Mary Namaganda Summary Principal Assistant Curator, Makerere University Herbarium, Land use changes in the Ssese include two critically endangered College of Natural Sciences, islands, Kalangala, have created a mammals, the Ssese island sitatunga PO Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda shift from six land use types (forests, or bushbuck (Tragelaphus sylvestris) [email protected] small scale agriculture, grasslands, and the endemic Lake Victoria swamp forests, wetlands and wooded rat (Pelemys isseli), and eight Red grasslands) to eight, including built List butterfly species of which four up areas, and oil palm plantations. are critically endangered (Acraea The sudden rise in built up areas now simulate, Epitola miranda, Euptera covering 10% of the land was almost elabontas, Neptis puella), two entirely at the expense of grasslands. endangered (Teratoneura isabellae, By 2006, large areas of forest, Thermoniphas togara) and two grassland, wetlands and wooded vulnerable (Pentila incospicua, grasslands had also been cleared Thermoniphas plurilimbata). There for oil palm plantations, resulting are also five endemic or endangered in loss in biodiversity. Kalangala plant species: Casearia runssorica, district is known for its unique Lasianthus seseensis, Lagarosiphon Pitadeniastrum-Uapaca forests that ilicifolius, Uvariodendron magnificum, support a high diversity of birds and Sabicea entebbensis. Besides and butterflies, but accurate data is habitat destruction, soil degradation deficient and -

Vote: 515 Kalangala District Structure of Budget Framework Paper

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 515 Kalangala District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Performance by Department Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 515 Kalangala District Foreword In accordance with Section 36 of the Local Government Act (Cap 243), Local Governments prepare appropriate plans and documents in conformity with Central Government guidelines and formats.In pursuance of the said Act, Kalangala District Local Government has prepared a Local Government Budget Framework Paper for the period 2017/18. This document was developed through a participatory process that brought on board different stakeholders in a bottom up planning approach starting at village level and climaxed by the District Budget conference held on 3rd November 2016 in which development partners participated among others. This document is derived from the approved 5 year District Development Plan for 2015/16 -2019/20. The Development Plans focuses on the following key strategic objectives; • To improve household incomes and promote food security, • To promote good governance, • To enhance local revenue collection using best practices, • To improve the stock and quality of water and road infrastructure. • To increase safe water coverage and sanitation in the District, • To increase access, quality and equity of education for girls and boys • To improvement in the quality of health care services, The District has however continued to experience Challenges; The allocation formular which the Government uses when allocating funds does not favour the District because it considers land area and not surface coverage yet the District has a total area of 9,066.8 sq km of which 432.1 sq km (4.8%) is land, the rest is water mass about 8,634.7 sq km(95.2%) without putting into consideration the many peculiar challeges including connectivity problems of moving from one Island to another which makes the costs of service delivery very high. -

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda National Red List for Uganda for the following Taxa: Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Butterflies, Dragonflies and Vascular Plants JANUARY 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team and authors of the Uganda Redlist comprised of Sarah Prinsloo, Dr AJ Plumptre and Sam Ayebare of the Wildlife Conservation Society, together with the taxonomic specialists Dr Robert Kityo, Dr Mathias Behangana, Dr Perpetra Akite, Hamlet Mugabe, and Ben Kirunda and Dr Viola Clausnitzer. The Uganda Redlist has been a collaboration beween many individuals and institutions and these have been detailed in the relevant sections, or within the three workshop reports attached in the annexes. We would like to thank all these contributors, especially the Government of Uganda through its officers from Ugandan Wildlife Authority and National Environment Management Authority who have assisted the process. The Wildlife Conservation Society would like to make a special acknowledgement of Tullow Uganda Oil Pty, who in the face of limited biodiversity knowledge in the country, and specifically in their area of operation in the Albertine Graben, agreed to fund the research and production of the Uganda Redlist and this report on the Nationally Threatened Species of Uganda. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... -

Entebbe Municipal Council

Lake Victoria City Development Strategies for Improved Environment and Poverty Reduction Entebbe Municipal Draft Profile BASIC INFORMATION ON ENTEBBE MUNICIPAL COUNCIL 1.0 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Entebbe municipality derives its name from the Luganda word ‘e ntebe’ (meaning ‘seat’ or ‘chair’) referring to the rocky seats on the shores of Lake Victoria which were carved by Mugula, a Muganda traditional Chief in the early 18th Century. Being a close confidant of the Kabaka (king of Buganda), Mugula wielded substantial administrative and judicial powers. Legend has it that this Chief carved out for himself seats in the rock from where he used to administer justice. Sentences meted out by Mugula ranged from simple fines to banishment to Ssese islands or even death by drowning in Lake Victoria. People visiting this place used to say that they were going to “Entebbe za Mugula’ or “Mugula’s seats”. Later it became fashionable to refer to the place simply as “Entebbe”. Although it had that traditional linkage to administration of justice Entebbe only became the capital city of Uganda in 1894 following a decision in 1893 by the then colonial Governor Sir Gerald Portal to relocate from Kampala. This decision was later rescinded by the independence Government and the capital reverted to Kampala leaving Entebbe with the State House, the International Airport and a few Ministry Headquarters and government departments. 1.1 GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES Physical Entebbe lies at 0o.04N, 320.280E and is 37 kilometers South East of Kampala the capital city of Uganda. It is situated in Wakiso District boarding Lake Victoria in the South. -

Assessing Connectivity Despite High Diversity in Island Populations of a Malaria Mosquito Christina Bergey, Martin Lukindu, Rachel Wiltshire, Michael C

Assessing connectivity despite high diversity in island populations of a malaria mosquito Christina Bergey, Martin Lukindu, Rachel Wiltshire, Michael C. Fontaine, Jonathan Kayondo, Nora Besansky To cite this version: Christina Bergey, Martin Lukindu, Rachel Wiltshire, Michael C. Fontaine, Jonathan Kayondo, et al.. Assessing connectivity despite high diversity in island populations of a malaria mosquito. Evolutionary Applications, Blackwell, 2020, 13 (2), pp.417-431. 10.1111/eva.12878. hal-02915424 HAL Id: hal-02915424 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02915424 Submitted on 25 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Received: 31 May 2019 | Revised: 28 August 2019 | Accepted: 27 September 2019 DOI: 10.1111/eva.12878 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessing connectivity despite high diversity in island populations of a malaria mosquito Christina M. Bergey1,2,3,4 | Martin Lukindu1,2 | Rachel M. Wiltshire1,2 | Michael C. Fontaine5,6 | Jonathan K. Kayondo7 | Nora J. Besansky1,2 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Abstract Dame, IN, USA Documenting isolation is notoriously difficult for species with vast polymorphic 2 Eck Institute for Global Health, University populations. High proportions of shared variation impede estimation of connectiv‐ of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA 3Department of Genetics, Rutgers ity, even despite leveraging information from many genetic markers. -

Care Old Age & Child (COAC) Foundation, Annual Review Report

[Care Old Age & Child (COAC) Foundation, Annual Review Report] 2018 ABSTRACT This is a report summary of the Care Old Age & Child (COAC) Foundation. It consists of a Foundation brief background, DNA (ideology). Further it gives an overview of the programs and projects that were undertaken, Achievements, Challenges, Recommendations, Conclusion and ends with an appendix of a few pictorials resulting from project reviews completed at the end of financial year that ended on Saturday 30 August 2019. ADDRESS COAC Foundation Uganda – East Africa Ssehab Hotel - Kalangala District P.O Box 23 Kalangala Tel: +256 -776-241566 Email: [email protected] www.careoldageandchildfoundation.org “Restoring Hope” ii [Care Old Age & Child (COAC) Foundation, Annual Review Report] 2018 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................ i List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... v ORGANIZATION BRIEF BACKGROUND .......................................................................... 1 Location of Kalangala District in Uganda ................................................................................... 1 Organizational DNA (Ideology) .................................................................................................. 1 Vision:…. ................................................................................................................................................. -

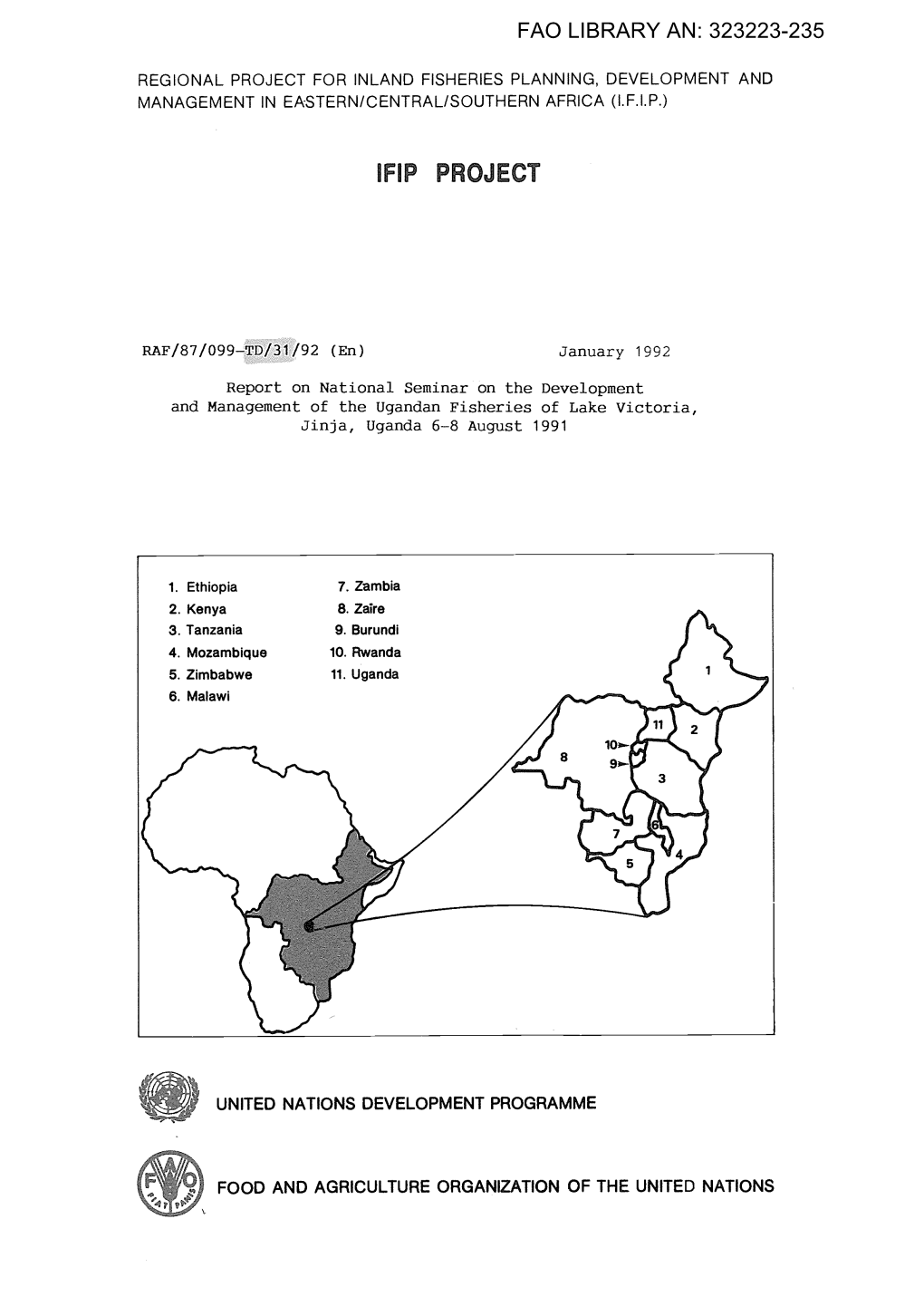

Ifip Project

REGIONAL PROJECT FOR INLAND FISHERIES PLANNING, DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT IN EA-STERN/CENTRAL/SOUTHERN AFRICA (I.F.I.P.) IFIP PROJECT RAF/87/099-WP/07/91 (En) July 1991 Proceedings of the Symposium on Socio-economic aspects of Lake Victoria Fisheries. Volume 2 (unedited papers 8-12). Ethiopia Zambia Kenya Zaire Tanzania Burundi Mozambique Rwanda Zimbabwe Uganda Malawi UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNDP/FAO Regional Projéct RAF/87/099-WP/07/91 (En) for Inland Fisheries Planning Development and Management in Eastern/Central/Southern Africa RAF/87/099-WP/07/91 (En) July 1991 Proceedings of the Symposium on Socio-economic aspects of Lake Victoria Fisheries. Volume 2 (unedited papers 8-12). FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Bujumbura, July 1991 The conclusions and recommendations given in this and other reports in the IFIP project series are those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. They may be modified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequent stages of the Project. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or UNDP concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. j j PREFACE The IFIP project started in January 1989 with the main objective of promoting a more effective and rational exploitation of thefisheries resources of major water bodies of Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. The project is executed by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), and funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for a duration of four years.