The Urban Poor and Housing in Nigeria 1999-2007: a Case Study of the Urban Poor and Housing Programme in Port Harcourt, Rivers State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of Human Rights Organizations in Sub

THE STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA The International Human Rights Internship Program and The Swedish NGO Foundation for Human Rights The Swedish NGO Foundation for Human Rights supports organizations and individuals working for human rights, primarily in Africa and Latin America/the Caribbean. Priority is given to non-profit, non-governmental efforts which stress the importance of popular participation. South-South coordination and interchange is encouraged. In Sweden the Foundation participates in the debate on human rights, addressing itself to the public through seminars and workshops, and initiating strategic studies. The International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP) seeks to strengthen human rights organizations through providing support for professional training and exchange opportunities for their staff. IHRIP supports development efforts of organizations in countries of the South, as well as East Central Europe and the former Soviet Republics. IHRIP is part of the Institute of International Education (IIE). The Swedish NGO Foundation for Human Rights International Human Rights Internship Program Drottninggatan 101 Institute of International Education S-113 60 Stockholm 1400 K Street, N.W., Suite 650 Sweden Washington, D.C. 20005 Telephone: (46)(8) 30 31 50 U.S.A. Fax: (46)(8) 30 30 31 Telephone: (1)(202) 682-6540 Fax: (1)(202) 962-8827 CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ i Overview Introduction .................................................................... -

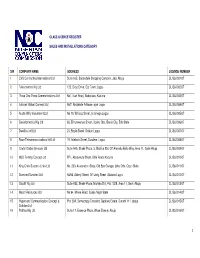

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

World Rural Observations 2019;11(3) WRO

World Rural Observations 2019;11(3) http://www.sciencepub.net/rural WRO Impact of Urban Renewal Projects on the Socio-Economic Groups in Port Harcourt Iyowuna F. Tubobereni1 and Opiriba K. Ikiriko2 1 & 2Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Science, Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic, Rumuola, P.M.B. 5936, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: The study reviewed urban renewal exercises embarked upon by the Rivers State Government from 1988 to 2019 in some parts of Port Harcourt metropolis, namely, Marine Base, Ndoki Water Front; Aggrey Road-end, and Rainbow Town, to ascertain the impact of the renewal schemes on the different socio- economic groups in the city. Primary and secondary sources of data, as well as participant observation techniques were utilized to obtain the data for the study. Our findings revealed that urban renewal exercises have led to the dislocation of social interactions; displacement of original residents, as a large majority of these residents are unable to meet the required initial deposit for occupation since there are no mortgage facilities even when allocation is made to them. A fall-out of the renewal schemes result in the creation of incidental spaces abutting the developments and are taken over by some of the displaced people leading to the situation that called for the renewal. However, in one of the renewal schemes (Rainbow Town), initial occupants are totally displaced due to the types and cost of the housing developments which are of the high socio-economic category. Displaced residents end-up establishing and proliferating further slums and squatter areas. -

Prevalence Pattern of Road Rage Across Traffic Routes in Port Harcourt Metropolis, Rivers State, Nigeria

International Journal of Scientific Engineering and Research (IJSER) ISSN (Online): 2347-3878 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 56.67 | Impact Factor (2017): 5.156 Prevalence Pattern of Road Rage across Traffic Routes in Port Harcourt Metropolis, Rivers State, Nigeria Amamilo, Chukwunenye Augustus1, Sampson Ugochi Sylvia2, Ukusowa, Mizaitul May Prince3 1, 2Department of Geography & Environmental Management, University of Port Harcourt, Port HarcourtChoba 3Department of Geography and Natural Resources Management, University of Uyo, Uyo Abstract: The study investigated the prevalencepattern of road rage across traffic routes in Port Harcourt Metropolis, Rivers State, Nigeria with view to identifying the types of road rage attitude and their effects on drivers, environment and vehicle. The study sampled a total of 352 drivers across the major motor parks/loading points in the study area.The obtaineddata was analysed descriptively using frequencies, percentages, tables and charts. Results showed that road rage behaviours such as tailgating, rude gestures, unsafe lane changes, verbal insult, bumper to bumper driving, running late, high speed chase, impatience were considered the most road rage in Port Harcourt Metropolis. Findings also showed that causes of road rage includeddriving behaviour such as tailgating (46.3%), gridlocks (15.3%), poor road condition (13.15), poor traffic control (11.3), and lack of public mass transit (14.2) and amongst others. Ikwerre Road recorded a high level of road rage manifestation, followed by Aba road and East-west road respectively. Therefore, the research recommends that, drivers should undergo adequate training and sensitisation on driving skills,and other related road traffic signs and its dangers, while relevant government agencies should ensure proper implementation and monitoring of various road traffic laws, etc. -

The Legend and the Man Mangiri

The Legend and the Man Mangiri THE LEGEND AND THE MAN Mangiri, Stanley Golikumo (Ph.D) Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Niger Delta University, Wiiberforce Island Bayeisa State, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract Every artist of every age do impact the people and environment which he belongs. As such many Nigerian artists have expressed themselves through their art works in different media on the social, cultural, political, and economic experiences in various degrees, qualities, and techniques. Many of these artists have been studied in some ethnic groups in Nigeria but not much attention has been given to the study of artists of Ijo of the Niger Delta. The artists of I jo ethnic groups appear to have been over - sighted by researchers. Hence, the research focused on the study of Jackson Ayarite Waribugo - his status, family life, works of art and their influence on the society. This is also aimed at terminating the era of publications on Ijo which reflects the Western perception of the region. That is hope of a new approach towards the understanding of the ijo, its artists, its works of art, its people and its vast potential. The paper attempts to present a detailed record of modern Ijo artistic heritage. Instruments such as interview, and photographic recordings of visuals were used to achieve the desired objective. The study reveals that the artist combined perceptual and conceptual tendencies by expressing cultural identity through the use of Western idioms. At the same time, it provides basic information on the activities of each zone as an integral part of the national and international community. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2015 STERLING BANK PLC TABLE OF CONTENTS Notice of AGM Governance Basic Information Overview Leadership – Corporate The Management Team 182 056 Governance Report Why Integrated Reporting 006 Branch Network 184 Directors, Officers and 060 Performance Highlights 007 Professional Advisers Change of Address Form 193 Chairman’s Statement 008 Board of Directors 061 E-bonus/offer/rights Form 195 Report of the Directors 066 Mandate for Dividend Payment to Bank 197 Strategic report Statement of Directors’ (e-dividend form) Responsibilities in relation to 073 Managing Director/ Chief Shareholder’s Data Update 012 the Financial Statements 199 Executive Officer’s Report Form Our Strategy/Business Model 018 Report of the External Consultants on the Board 074 Proxy Form 201 Key Performance Indicators 027 Appraisal of Sterling Bank Plc Economic Report 028 Independent Auditors’ Report 075 Performance Review 031 Report of Statutory Audit 077 Committee Statement of Compliance 078 Sustainability Sustainability Approach 044 Enriching Lives 044 Financial statements Education 045 Statement of Profit or Loss Environment 047 and other Comprehensive 080 Income Entertainment 049 Statement of Financial Community Development 050 081 Position Customer Service Initiatives 050 Statement of Changes in 082 For our Employees 051 Equity For our Shareholders 051 Statements of Cash Flows 084 Statement of Prudential For the Government 052 085 Adjustments Materiality Analysis 052 Notes to the Financial 086 Stakeholder Engagement 053 Statements Statement of Value Added 177 Five-year Financial Summary 178 Share Capital History 180 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2015 STERLING BANK PLC NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the 54th Annual General Meeting of Sterling Bank Plc will be held at Eko Hotel & Suites, Plot 1415, Adetokunbo Ademola Street, Victoria Island, Lagos on Tuesday, the 19th day of April, 2016 at 10.00 a.m. -

Port Harcourt, Nightmare, City, Garden, Population, Rivers State

World Environment 2014, 4(3): 111-120 DOI: 10.5923/j.env.20140403.03 Port Harcourt, the Garden City: A Garden of Residents Nightmare Kio-Lawson D.*, Dekor J. B. Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria Abstract Port Harcourt, the administrative and commercial capital of oil Rivers State is referred to as the Garden city of Nigeria because of its richness in greenery. With a high concentration of economic opportunities coupled with a well developed transportation network the city was quick to emerge as the nerve centre of economic activities in the Niger Delta as well as one of the most industrialized cities in Nigeria. From a small population of 235,098 in 1963, its current population stands at 1.5 million. This astronomical increase in population is not without its own problem. The city today is regarded as one of the most congested cities in Nigeria with several nightmarish problems facing both the government and residents. This paper clinically examined these problems as they are with the aim of providing answer to the question of “what is to be done” to tackle the problems effectively. This paper was able to establish that the failure of the government to meet up its social responsibility to the people is largely responsible for most of the problems experienced by residents in the city. This work was made possible after several months of intense field work. Primary data collected through personal observation, face-to-face interview and discussion with residents of the city was very helpful. Past works of previous scholars relating to this research also contributed greatly to the success of this research. -

A Gis Based Road Network of Port Harcourt, Nigeria

A Gis Based Road Network of Port Harcourt, Nigeria Amina DIENYE and Ajie EMMANUEL, Nigeria. Key words: Road Network, GIS, Traffic Congestion, Port Harcourt, GPS. SUMMARY This is a summary on the paper on GIS based Road Network of Port Harcourt. The issue of an improved road network due to the dynamic and massive development of Port Harcourt calls for serious concern and adequate attention. The recent physical developmental projects within the metropolis, for example, the construction of a flyover along Ikwerre road, and the expansion of Ada- George road resulted in the demolition of structures because the government intends to create a conducive and optimized road network system. The aim of this work is to develop a Geographic Information System (GIS) based road network map of Port Harcourt city that can be used to analyze traffic congestion within the city and suggest possible solutions. The handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) was used to acquire geographic coordinates of major locations experiencing traffic jams, bad spots and schools. The transformed GPS coordinates were added to the ArcGIS environment to define the spatial locations. Prior to that, the road map was digitized and geo-rectified. Satellite Imagery from the remote sensing technology was used to acquire data of new roads, for map updating and revision. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) operations (buffering, overlay and networking techniques’) using Arc GIS 9.3 were performed on the road map signifying the versatility of GIS. The study recommends that; the road -

Noise Levels and Frequency Response from Religious Houses in Portharcourt City Local Government Area

International Journal of Environmental Protection and Policy 2019; 7(1): 24-31 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijepp doi: 10.11648/j.ijepp.20190701.14 ISSN: 2330-7528 (Print); ISSN: 2330-7536 (Online) Noise Levels and Frequency Response from Religious Houses in Portharcourt City Local Government Area Ononugbo Chinyere Philomina 1, *, Avwiri Eseroghene 2 1Department of Physics, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2Department of Curriculum Studies and Educational Technology, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Ononugbo Chinyere Philomina, Avwiri Eseroghene. Noise Levels and Frequency Response from Religious Houses in Portharcourt City Local Government Area. International Journal of Environmental Protection and Policy . Vol. 7, No. 1, 2019, pp. 24-31. doi: 10.11648/j.ijepp.20190701.14 Received : January 15, 2019; Accepted : February 25, 2019; Published : March 16, 2019 Abstract: Introduction: Noise pollution in churches is one of the health challenges facing developing nations of the world. Both Pastors/Reverends are exposed to different sound levels during church services, many of which can last for hours. According to the Nigerian National Environmental standard and regulation Act 2007, the maximum permissible noise level in worship centers should not exceed 75 dB and Nigeria being the highest church proliferation in the world makes it imperative to carry out this research. Aim: the aim of this study is the measure the equivalent noise levels with their corresponding frequency levels at varying distances from the source and quantify the noise pollution levels in churches and mosques in Port Harcourt. Method: a total of 11 Pentecostal churches, 5 orthodox churches and 3 central mosques were randomly selected. -

Foreign Exchange Auction No 50/2004 of 30Th June, 2004 Foreign Exchange Auction Sales Result Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

1 CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO 50/2004 OF 30TH JUNE, 2004 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK Weighted S/N A. QUALIFIED BIDS M/A NO. R/C NO. APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT AMOUNT PURPOSE NAME Average 1 OSITELU OLADIPO A. AA 0533863 A 2058155 12 ADENIJI STREET, SURULERE. 134.0000 5,000.00 5,000.00 SCHOOL FEES MAGNUM 0.0082 2 ESTHER MSHELIA AA1387744 A0125656 NO 20C ABUJA ROAD,KADUNA 134.0000 5,130.00 10,130.00 SCHOOL FEES PRUDENT 0.0084 3 F U OKAGBA INDUSTRIES LTD MF 0279722 RC 447489 75A OZOMAGALA STREET, ONITSHA 133.5000 37,800.00 47,930.00 IMPORTATION OF GLASS SHEETS FSB 0.0617 4 SMMS NIG LTD MF 0613501 RC 383255 SHADE B1/C2 MONDAY MARKET, MAIDUGURI, BORNO S 133.5000 21,600.00 69,530.00 IMPORTATION OF 36MT OF KAYU BOYA CUT PIECES FSB 0.0352 5 LIFE LINE INVESTMENT MF 0412020 RC 230889 105 OJUELEGBA ROAD SURULERE LAGOS 133.5000 12,000.00 81,530.00 CHRISTIAN BOOKS FTB 0.0196 6 LIFETIME SUCCESS NIGERIA CO. MF0412140 LAZ137728 57,OBA ADEYINKA OYEKAN, IDUMAGBO AVENUE, LAGO 133.4500 6,000.00 87,530.00 CAMEL' BRAND ASPHALT ROOFING FELT FTB 0.0098 7 BENCOD PRESS LTD MF0270206 52000 KM 3, LAGOS - BADAGRY ROAD,ORILE IGANMU ,LAGOS 133.2500 32,400.00 119,930.00 COLOURED MANILLA BOARD IN SHEET FBN 0.0527 8 ASOLAD VENTURES NIG LTD MF0468059 346552 S7/1301, IRE -AKARI CLOSE FELELE IBADAN OYO STATE 133.0000 26,902.00 146,832.00 NEW PACKAGES CAPPING AND SHRINK MACHINE AFRI 0.0437 9 Babiss Ventures Ltd MF 0465468 RC 145924 6,Ogabi Street,Abule -Ijesha,Yaba,Lagos 133.0000 23,760.00 170,592.00 White Sticker Paper,Cartons(Goods Are New) Capital 0.0386 10 OSISI UGONNA RAPHAEL AA1413171 A0375840 46, MODUPE JOHNSON CRESCENT, SURULERE, LAGOS 133.0000 1,460.00 172,052.00 PTA CHARTERED 0.0024 11 GOODWILL INDUSTRIAL VENTURES LTD MF0463382 RC2614326 42, BISHOP OLUWOLE STREET, VICTORIA ISLAND 133.0000 10,000.00 182,052.00 CHANGEOVER SWITCHES CITZENS 0.0162 12 OSCAR MASTERS NIG. -

Televangelism and the Socio-Political Mobilization of Pentecostals in Port Harcourt Metropolis: a Kap Survey

Godwin Okon1 Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Оригинални научни рад Port Harcourt, Nigeria UDK: 279.125(669) ; 316.77:2-475(669) TELEVANGELISM AND THE SOCIO-POLITICAL MOBILIZATION OF PENTECOSTALS IN PORT HARCOURT METROPOLIS: A KAP SURVEY Abstract This study was borne out of the need to ascertain the extent to which televangelists in Port Harcourt; deploy media content towards issues that border on socio-political development. The primary objective was to empirically determine if a correspondence exists between advocacy by televangelists and compliance by Pentecostals as mani- fested in Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP). The study necessitated triangulation with the Weighted Mean Score (WMS) as the basis for quantitative analysis. Findings revealed televangelism to revolve around the pastor (p), message (m) and church (c). Though an association link was found between ideologies expressed by televange- lists and adoption by Pentecostals, this link only found expression in the concepts of secularism and fundamentalism. Survey also revealed a dismal rating of televangelism as regards socio-political mobilization. The chi-square test showed the x2 computed to be greater than the x2 critical thus showing a disconnect between knowledge on the potential benefits of televangelism and the deployment of such benefits towards socio-economic mobilization by televangelists. It was therefore recommended that televangelism should not be used for self aggrandizement and church growth but should complement the socio-political mobilization process. It was further recom- mended that a policy framework should be put in place to ensure compliance by tel- evangelists. Key words: Mobilization, Pentecostal, Socio-Political, Televangelism, Televange- list. -

Government of Rivers State of Nigeria Committee for the Accreditation Status and Approval of Private Schools Summary Sheet

GOVERNMENT OF RIVERS STATE OF NIGERIA COMMITTEE FOR THE ACCREDITATION STATUS AND APPROVAL OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS SUMMARY SHEET RIVERS SOUTH-EAST OYIGBO LGA S/N NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL ADDRESS ACCREDITATION Alpha Missionary Group of Schools 1 1 Alpha Close by Ohita Lane, Oyigbo INTERIM (Secondary) Anerobi International College 2 Afam Rd, Izuoma, Oyigbo INTERIM (Secondary) Bee Mec Model School (Nursery & 3 Izioma Asa Oyigbo INTERIM Primary) No 3 Unity Avenue, Off Isaiah Eletue Street, 4 Blessed Model Secondary School INTERIM Oyigbo Bravery Int'l School (Nursery & 5 9 Chris Avenue, Off 117 Afam Road, Oyigbo INTERIM Primary) Bright Kids Academy (Nursery & 6 Double Portion Avenue/Ogboso Obeama INTERIM Primary) 7 C. Conud Brain International School 6/7 Eberechi Str, Komkom, Oyigbo INTERIM 8 Calebs Model School Afam-Okoloma INTERIM Calvary Stars Montessori Group of Chief Nwadike Street off Tiper Park/seventh 9 INTERIM Schools (Nursery & Primary) days Adventist Church Mirinwayi-Asa Oyigbo 10 Champions Missionary School 33 Ekweru Ave, Mbano-Camp, Oyigbo INTERIM 3 Ndikelionwu Str, Satellite Village, Near 11 Charlaw Preparatory Academy INTERIM Timber Mkt, Oyigbo NO. NEW JERUSALEM, UMUEKE OBEAMA- 12 CHEZ BRAIN ACADEMY (Secondary) INTERIM ASA, OYIGBO 13 Chidan International School 1 Stino Close, Off Ehi Rd, Oyigbo INTERIM Chimac International School 14 Jeremiah Nwaji Str, Behind Bush Bar, Oyigbo INTERIM (Secondary) Covenant Joint Heirs Montessori 15 4 Umukam Street Oyigbo INTERIM Schools (Nursery & Primary) DAiLY quintessential QUEENS & KING 30 NWEKE STREET, Off Umusoya Road, 16 INTERIM ACADEMY (SECONDARY SCHOOL) OYIGBO No 11 Onyeche Street Okpulor Beside 17 De Kindlers' Int'l (Nursery & Primary) INTERIM Assemblies of God DE-SHILOH'S SCHOOL (NURSERY & OPPOSITE BISHOP OKOYE SECONDARY 18 INTERIM PRIMARY) SCHOOL, MIRINWANYI OYIGBO St.