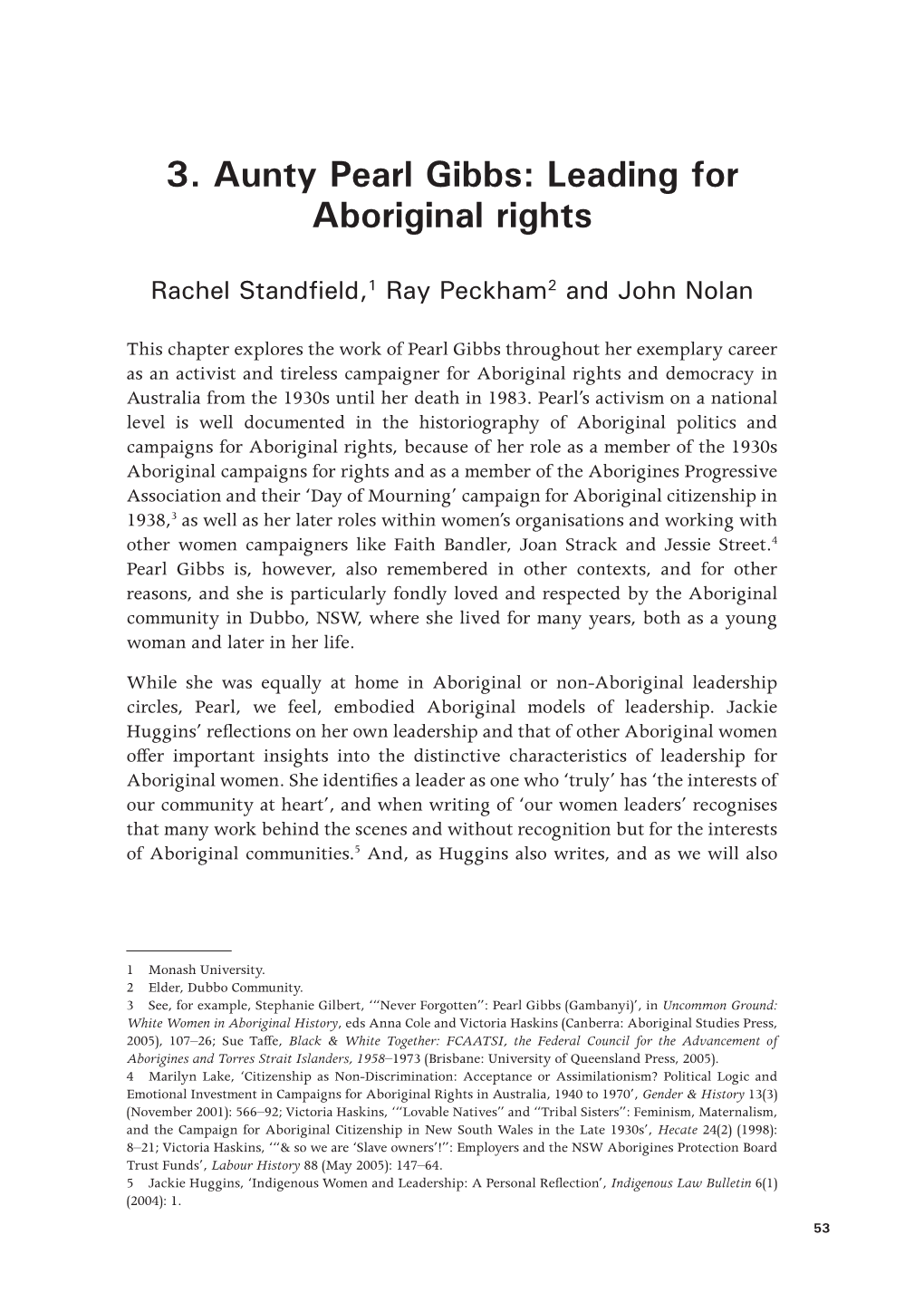

3. Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time F aith Bandler 1920–2015 Civi l Rights Activist This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 2 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Faith Bandler Director/Producer Frank Heimans Executive Producer Ron Saunders Duration 26 minutes Year 1993 © NFSA Also in Series 2: Franco Belgiorno-Nettis, Nancy Cato, Frank Hardy, Phillip Law, Dame Roma Mitchell, Elizabeth Riddell A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: FAITH BANDLER 2 SYNOPSIS How did the sugar industry benefit from the Islanders? What does this suggest about the relationship between labour and the success Faith Bandler is a descendant of South Sea Islanders. At the age of of industry? 13, her father was kidnapped from the island of Ambrym, in what Aside from unequal wages, what other issues of inequality arise is known as Vanuatu, and brought to Australia to work as an unpaid from the experiences of Islanders in Queensland? labourer in the Queensland cane fields. -

SEVEN WOMEN of the 1967 REFERENDUM Project For

SEVEN WOMEN OF THE 1967 REFERENDUM Project for Reconciliation Australia 2007 Dr Lenore Coltheart There are many stories worth repeating about the road to the Referendum that removed a handful of words from Australia’s Constitution in 1967. Here are the stories of seven women that tell how that road was made. INTRODUCING: SHIRLEY ANDREWS FAITH BANDLER MARY BENNETT ADA BROMHAM PEARL GIBBS OODGEROO NOONUCCAL JESSIE STREET Their stories reveal the prominence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women around Australia in a campaign that started in kitchens and local community halls and stretched around the world. These are not stories of heroines - alongside each of those seven women were many other men and women just as closely involved. And all of those depended on hundreds of campaigners, who relied on thousands of supporters. In all, 80 000 people signed the petition that required Parliament to hold the Referendum. And on 27 May 1967, 5 183 113 Australians – 90.77% of the voters – made this the most successful Referendum in Australia’s history. These seven women would be the first to point out that it was not outstanding individuals, but everyday people working together that achieved this step to a more just Australia. Let them tell us how that happened – how they got involved, what they did, whether their hopes were realised – and why this is so important for us to know. 2 SHIRLEY ANDREWS 6 November 1915 - 15 September 2001 A dancer in the original Borovansky Ballet, a musician whose passion promoted an Australian folk music tradition, a campaigner for Aboriginal rights, and a biochemist - Shirley Andrews was a remarkable woman. -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do -

![Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] P412c-412C Hon Darren West](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5532/extract-from-hansard-council-thursday-19-february-2015-p412c-412c-hon-darren-west-705532.webp)

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] P412c-412C Hon Darren West

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] p412c-412c Hon Darren West FAITH BANDLER Statement HON DARREN WEST (Agricultural) [5.19 pm]: My statement will be brief. I rise this evening with a little sadness as I would like to address and share with the house the recent passing of Faith Bandler. Faith Bandler was born in Tumbulgum in New South Wales in 1918, the daughter of a Scottish–Indian mother and Peter Mussing, who had been blackbirded in 1883 from Ambrym Island, Vanuatu—known then as the New Hebrides. At 13 years of age he was sent to Mackay, Queensland to work on a sugarcane plantation. He escaped and married Faith Bandler’s mother. Faith Bandler cited stories of her father’s harsh experience as a slave labourer as a strong motivation for her activism. Her father died in 1924 when Faith was five. During World War II, Faith and her sister, Kath, served in the Australian Women’s Land Army. Indigenous women received less pay than white workers. After her discharge in 1945, she started a campaign for equal pay for Indigenous workers. In 1952, Faith married Hans Bandler, a Jewish refugee from Vienna. They had a daughter, Lilon Gretl, and fostered a son, Peter. In 1956, Faith became a full-time activist, becoming involved in the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, which was formed in 1957. During this period, Faith led the campaign for a constitutional referendum to remove discriminatory provisions from the Constitution of Australia. This campaign included petitions and public meetings, resulting in the 1967 referendum succeeding in all six states with 91 per cent support. -

With Fond Regards

With Fond Regards PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by ELIZABETH RIDDELL ith Fond Regards W holds many- secrets. Some are exposed, others remain inviolate. The letters which comprise this intimate book allow us passage into a private world, a world of love letters in locked drawers and postmarks from afar. Edited by noted writer Elizabeth Riddell, and drawn exclusively from the National Library's Manuscript collection, With Fond Regards includes letters from famous, as well as ordinary, Australians. Some letters are sad, others inspiring, many are humorous—but all provide a unique and intimate insight into Australia's past. WITH FOND REGARDS PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by Elizabeth Riddell Compiled by Yvonne Cramer National Library of Australia Canberra 1995 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1995 Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publishers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry With fond regards: private lives through letters. ISBN 0 642 10656 8. 1. Australian letters. 2. Australia—Social conditions—1788-1900. 3. Australia—Social conditions—20th century. 4. Australia—Social life and customs—1788-1900. 5. Australia—Social life and customs— 20th century. I. Riddell, Elizabeth. II. Cramer, Yvonne. III. National Library of Australia. A826.008 Designer: Andrew Rankine Editor: Susan -

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left Terry Townshend 2 The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left About the author Terry Townsend was a longtime member of the Democratic Socialist Party and now the Socialist Alliance. He edited the online journal Links (links.org) and has been a frequent contributor to Green Left Weekly (greenleft.org.au). Note on quotations For ease of reading, we have made minor stylistic changes to quotations to make their capitalisation consistent with the rest of the book. The exception, however, concerns Aborigines, Aboriginal, etc., the capitalisation of which has been left unchanged as it may have political significance. Resistance Books 2009 ISBN 978-1-876646-60-8 Published by Resistance Books, resistanceboks.com Contents Preface...........................................................................................................................5 Beginnings.....................................................................................................................7 The North Australian Workers Union in the 1920s and ’30s.....................................9 Comintern Influence..................................................................................................12 The 1930s....................................................................................................................15 Aboriginal-Led Organisations & the Day of Mourning............................................19 Struggles in the 1940s: The Pilbara Stock Workers’ Strike........................................23 The 1940s: Communists -

Faith Bandler Ac - Condolences

COUNCIL 23 FEBRUARY 2015 ITEM 3.3. FAITH BANDLER AC - CONDOLENCES FILE NO: S051491 MINUTE BY THE LORD MAYOR To Council: On 27 May 1967, over 90 per cent of Australians voted to amend the Commonwealth Constitution to advance the position of Aboriginal Australians. That vote, the highest ever recorded at an Australian referendum, was the outcome of a campaign waged for more than 10 years. On 13 February 2015, Faith Bandler, one of the tireless leaders of that campaign, was lost to Australia. Faith Bandler was born on 13 February 1918 of a South Seas Islander father and a Scottish-Indian mother. Her father, Peter, had been kidnapped from his home on Ambrym Island, Vanuatu at around 13 years of age and transported to Queensland where he was forced to work on a sugar cane plantation. He later escaped to NSW where he met and married Faith’s mother. They established a small banana farm near Murwillumbah where Faith spent her early years. While Faith did not know her father well (he died when she was five years old), stories about his harsh experiences as a slave labourer strongly influenced her activism. Faith moved to Sydney in 1934, living in Kings Cross, later admitting she “always had a yen for bright lights” and “wanted to have a life of my own”. She completed a short apprenticeship in a shirt factory and worked for a time making clothes. When World War II started, she joined the Women’s Land Army, and worked on fruit farms. While working in the Riverina, she first “saw the appalling conditions that Aborigines lived in”. -

Eternally Yours Message Digital Citizenship ‘Digital Disruption’ Is a Common Term in Contemporary Ontents Business

–Magazine for members Winter 2016 Eternally yours Message Digital citizenship ‘Digital disruption’ is a common term in contemporary ontents business. It highlights the pervasive changes wrought by Winter 2016 digital technologies on almost all aspects of the economy, employment, entertainment and our personal lives. Long established services such as the post office and the 4 WORLD PRESS PHOTO 16 28 CURATOR’S CHOICE Token of respect media industry have been profoundly disrupted. 6 NEWS Libraries have been similarly disrupted but — perhaps Calling all family 32 COLLECTION CARE because we have been using computers for five decades historians Home currency and online services since the 1970s — we have been able Robot reader to benefit from the developing digital technologies. Many cultures 34 NEW ACQUISITIONS By exploiting opportunities, libraries are now in a golden Looking for a Best in show age of service and value to their communities. typewriter indyreads Many of the initiatives by government and large Wipe Interrobang enterprises can be challenging for the public. Examples SL Monster atlas include online forms for social security claims, job THE MAGAZINE FOR STATE LIBRARY OF NSW FOUNDATION MEMBERS, MACQUARIE STREET ON THIS DAY FRIENDS AND VOLUNTEERS 8 applications, tax returns and, most recently, in plans for SYDNEY NSW 2000 38 LEARNING IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY the 2016 census. Libraries are responding actively to these BY THE LIBRARY COUNCIL PHONE (02) 9273 1414 Virtual excursions 10 EXHIBITION OF NSW. FAX (02) 9273 1255 challenges to assist their clients by providing computers Colour in darkness WINTER 2016 ENQUIRIES.LIBRARY@ FOUNDATION and WiFi, as well as training and support. -

A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family

Chapter 7 Race relations, work and education, 1964 to 1968 I returned to Australia in 1964 to find Aboriginal issues in New South Wales very different from those I left behind. In South Australia bureaucrats identified Aborigines as being persons of ‘full-blood’, others of Aboriginal descent were regarded as ‘state wards’, mainly those who were living on southern reserves. Then there were those people of Aboriginal descent who were classified as non- Aborigines because they had been given a State government exemption from the Protection legislation. Persons holding an Exemption Certificate had what was known in common practice as a ‘dog tag’. And finally, there were those people of Aboriginal descent who refused to conform to government policy because they believed it would demean them as ‘honorary whites’ if they did so. The exemption system in New South Wales was more that of failed assimilation policies. Despite the government’s parsimony, there were benefits for some individuals. Although the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (NSW) existed, the Welfare Board was not totally blind to the idea that urban life together with social conformity needed a measure of economic resources. There were no fringe benefits for education but there was for housing in city urban areas. On the downside Aborigines were not permitted to create organisations in opposition to government policies. However, some organisations deemed illegal under the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (NSW) did exist but were not prosecuted. The Aborigines and their friends who ran these organisations were courageous and enlightened people. This chapter is not only about my re-education, but about race relations and how it shifted between racial politics and socialisation practice. -

Productions by Sydney New Theatre

Productions by Sydney New Theatre Legend *Plays by Australian authors (C)New Theatre’s Children’s Theatre DirDirector AssocDirAssociate Director AsstDirAssistant Director DesDesigner StDesSet Designer CstDesCostume Designer MasksMasks Coordinator/Designer DramatDramaturg ChorChoreographer MusDirMusical Director RepRepetiteur MmtMovement Director FightsFights Director LDesLighting Designer SdDesSound Designer VideoVideo Production CompComposer Dial/VoiceDialect/Voice Coach SingSinging Coach ProdMgrProduction Manager StMgrStage Manager GrPublicity/Graphics Note: All dates with plays represent the official opening of the production and are researched as correct up to time of publication 1 of 81 5 * A Night in Spain 1933 * In Spain Dir: Frank Whyte 1934 r * The Tart Shop The Worke s’ Art Players Dir: Nellie Rickie 1 Vanzetti in the Death House Various hired venues * In Heaven (monologue by Edward Janshewsky) and 36a Pitt Street, Dir: Nellie Rickie plus other items * The Wrestlers 19 May First Floor Dir: Alf Grant (Workers’ Art Club) Cast including: Victor Arnold 2 Pygmalion 1 The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists Bill Brown Jim Burns Bernard Shaw Robert Tressall Dir: Valerie Wilson adapted Harry Broderick Doreen Dorrington Nat Finey StDes: Charles Kitchener Dir: Harry Broderick LDes: Jack Lewis Music: Mrs Saul’s orchestra Cleo Grant Harry Haddy Music: Mrs Larcher Workers’ Art Theatre Group cast including: Cast: P Christensen Isabelle Hull Charles Kitchener Victor Arnold Jack Ellis William Galmes Harry Haddy Reg Lewis Tom Morrison Charles Kitchen -

Papers on Parliament Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series, and Other Papers

Papers on Parliament Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series, and other papers Number 68 December 2017 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X (online ISSN 2206–3579) Published by the Department of the Senate, 2017 ISSN 1031–976X (online ISSN 2206–3579) Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Procedure and Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Ruth Barney All editorial inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director Procedure and Research Section Department of the Senate PO Box 6100 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3078 Email: [email protected] To order copies of Papers on Parliament On publication, new issues of Papers on Parliament are sent free of charge to subscribers on our mailing list. If you wish to be included on that mailing list, please contact the Procedure and Research Section of the Department of the Senate at: Telephone: (02) 6277 3074 Email: [email protected] Printed copies of previous issues of Papers on Parliament may be provided on request if they are available. Past issues are available online at: www.aph.gov.au/pops Contents Small Parties, Big Changes: The Evolution of Minor Parties Elected to the Australian Senate 1 Zareh Ghazarian Government–Citizen Engagement in the Digital Age 23 David Fricker Indigenous Constitutional Recognition: The 1967 Referendum and Today 39 Russell Taylor The Defeated 1967 Nexus Referendum 69 Denis Strangman Parliament and National Security: Challenges and Opportunities 99 Anthony Bergin Between Law and Convention: Ministerial Advisers in the Australian System of Responsible Government 115 Yee-Fui Ng Trust, Parties and Leaders: Findings from the 1987–2016 Australian Election Study 131 Sarah Cameron and Ian McAllister iii Contributors Zareh Ghazarian is a lecturer in politics and international relations in the School of Social Sciences at Monash University. -

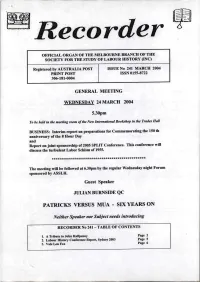

SIX YEARS on Neither Speaker No

✓ li., OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE MELBOURNE BRANCH OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY (EVC) Registered by AUSTRALIA POST ISSUE No 241 MARCH 2004 PRINT POST ISSN 0155-8722 306-181-0004 GENERAL MEETING WEDNESDAY 24 MARCH 2004 5.30pm To be held in the meeting room ofthe New International Bookshop in the Trades Hall BUSINESS: Interim report on preparations for Commemorating the 150 th anniversary of the 8 Hour Day and Report on joint sponsorship of 2005 SPLIT Conference. This conference will discuss the turbulent Labor Schism of 1955. *********************************************** The meeting will be followed at 6.30pm by the regular Wednesday night Forum sponsored by ASSLH. Guest Speaker JULIAN BURNSIDE QC PATRICKS VERSUS MUA - SIX YEARS ON Neither Speaker nor Subject needs introducing RECORDER No 241 - TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. A Tribute to John Halfpenny Page 2 2. Labour History Conference Report, Sydney 2003 Page 5 3. Vale Len Fox Page 6 Iiliiii- n r''t tr''YiiT '' '"■iliriaaii'r I I I w 1*11111 iiMh»<iliiiiii ir"f lim Politics is the Art of Turning Minorities into Majorities'^ A Tribute to John Halfpenny (1935- 2003) By Cheryl Wragg^ & Peter Gibbons^ John Hal^enny was a leader of Australian trade unionism and working people. His impact helped shape both state and national ind\istrial & political landscapes through the 1960s,'70s, '80s and '90s. A vigorous and influential advocate, campaigner and activist, John's union leadership, administrative skills and breadth of activity were a daily testament to his intellectual and organising brilliance. The recent passing of John HalQienny signals the end of an era in Australian progressive politics.