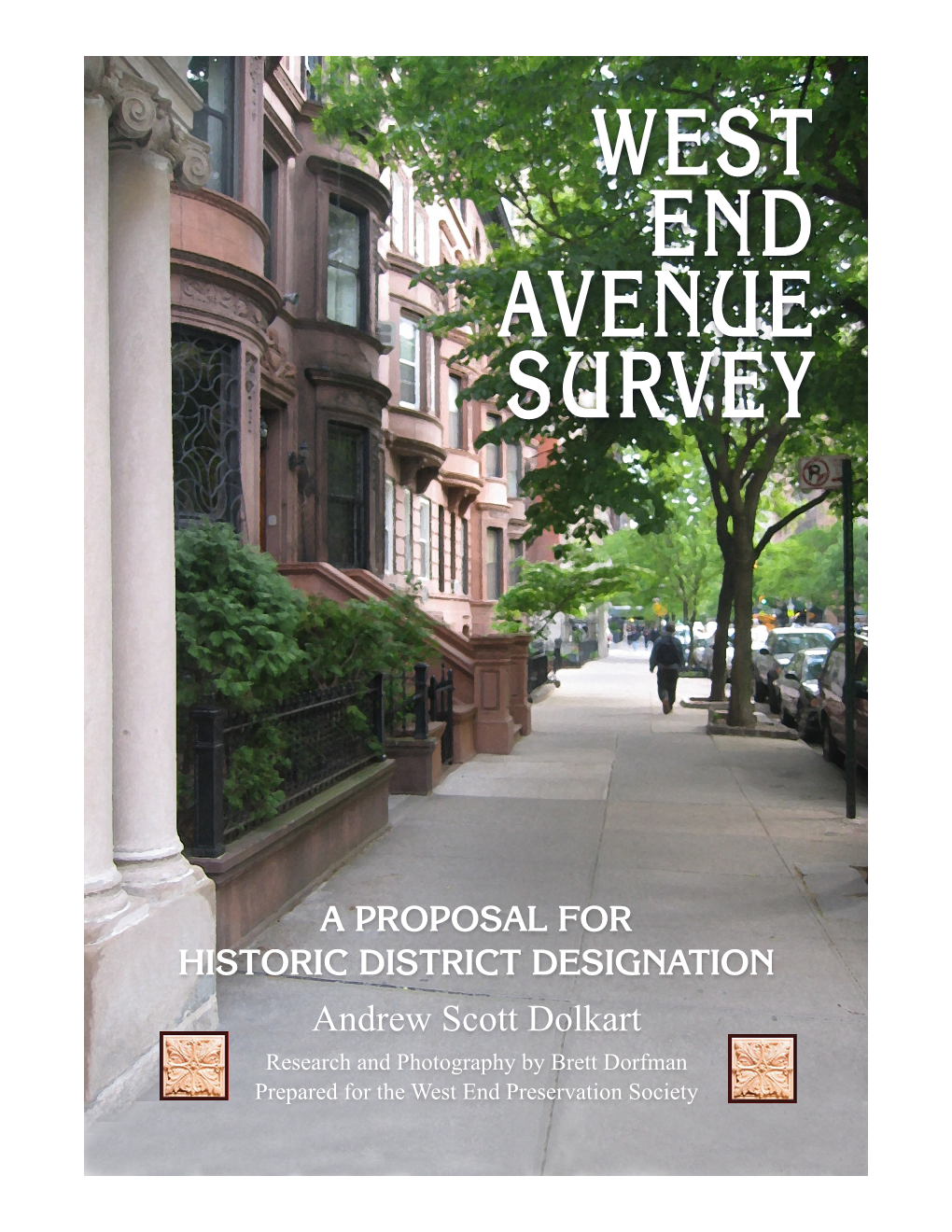

West End Avenue Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC ADZONE™ Detailsve MIDTOWN EAST AREA Metropolitan Mt Sinai E 117Th St E 94Th St

ve y Hudson Pkwy Pinehurst A Henr W 183rd St W 184th St George W CabriniW Blvd 181st St ve ashington Brdg Lafayette Plz ve Colonel Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St W 180th St Saint Nicholas A er Haven A Trans Mahattan Exwy W 182nd St 15 / 1A W 178th St W 179th St ve Laurel Hill T W 177th St Washington Brdg W 178th St Audubon A Cabrini Blvd ve W 176th St ve W 177th St Riverside Dr Haven A S Pinehurst A W 175th St Alexander Hamiliton W 172nd St W 174th St Brdg ve W 171st St W 173rd St W 170th St y Hudson Pkwy Pinehurst A Henr ve W 184th St W 169th St W 183rd St 14 y Hudson Pkwy George W Lafayette Plz CabriniW Blvd 181st St ve Pinehurst A ashington Brdg ve High Brdg W 168th St Henr W 183rd St W 184th St ve Colonel High Bridge Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St y Hudson Pkwy Cabrini Blvd W 180th St George W W 165th St Lafayette Plz W 181st St ve Pinehurst A Park ashington Brdg Henr Saint Nicholas A er Haven A TransW Mahattan 184th St Exwy W 182nd St Presbyterian 15 / 1A W 183rd St ve Colonel W 167th St Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St Hospital ve Cabrini Blvd W 179th St W 180th WSt 178th St ve George W Lafayette Plz W 181st St Jumel Pl ashington B W 166th St ve Laurel Hill T W 163rd St Saint Nicholas A er rdg Haven A Trans Mahattan Exwy W 182nd St W Riverside Dr W 177th St ashington Brdg ve 15W 164th / 1A St Colonel Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd StW 178th St Audubon A W 162nd St ve e W 166th St Cabrini Blvd v W 180th St ve W 179th St ve A W 178th St W 176th St W 161st St s Edgecombe A W 165th veSt Saint Nicholas A W 177th St er Laurel Hill T Haven A a W 182nd St Transl -

Pomander Walk

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 14, 1982, Designation List 159 LP-1279 POMANDER WALK, Numbers 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, Pomander Walk, 261, 263,265,267, West 94th Street, and 260,262,264,266,270,272,274, West 95th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1921; architects King & Campbell. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1242, Lot 10 in part excluding the land on which the Healy Building at 2521-2523 Broadway is situated. On February 9, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Pomander Walk (Item No. 10). The hearing was continued to April 6, 1982 (Item No. 6). Both hearings were duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. A total of 71 witnesses spoke in favor of designation at the two hearings. There were four speakers in opposition to designation. In addition, the Commission has received many letters and p~titions in support of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS Pomander Walk extends through the middle of the square block bounded by Broad way and West End Avenue, 94th and 95th Streets, on Manhattan's Upper West Side. The complex is composed of sixteen two-story houses facing the private walk and ninethree-story and two two-story buildings facing onto the street. Pomander Walk has a unique sense of place; secluded from the street, the walk is a delightful world of picturesque dwellings replete with half timbering, gables, and other ver nacular Tudoresque embellishments. The almost magical atmosphere created by this small residential enclave was very much the intention of Thomas Healy, who in 1921, commissioned the architectural firm of King & Campbell to design a residential com plex that would recreate the village atmosphere of Lewis Parker's then popular period comedy, Pomander Walk. -

On Current New York Architecture

OCULUS on current new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 44, Number 3, November 1982 Southwest tower of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine is sheathed in scaffolding in preparation for resuming construction after a hiatus of 41 years. page2 Oculus Names and News Volume 44, Number 3, November 1982 ago were apprenticed to cut stone for the purpose ... Peter C. Pran has joined The Grad Partnership as Oculus Director of Design and Associate of Editor: C. Ray Smith the firm ... Harold Francis Pfister has Managing Editor: Marian Page Art Director: Abigail Sturges been appointed Assistant Director of Typesetting: Susan Schechter Cooper-Hewitt Museum to succeed Christian Rohlfing, who is retiring ... The New York Chapter of Joseph M. Valerio of the University of the American Institute of Architects Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of 457 Madison Avenue, Architecture and Urban Planning, and New York, New York 10022 Daniel Friedman, a graduate of the 212-838-9670 school, are the authors of Movie Pal,aces: Renaissance and Reuse George S. Lewis, Executive Director Cathanne Piesla, Executive Secretary published by Educational Facilities Laboratories . The National lnstitut~ Executive Committee 1982-83: for Architectural Education has Arthur I. Rosenblatt, President announced the following Fellowships Theodore Liebman, First Vice President for 1983: Lloyd Warren Fellowship 70th Richard Hayden, Vice President Paris Prize offering $25,100 in prizes Terrance R. Williams, Vice President for travel and/or study abroad, open to Alan Schwartzman, Treasurer participants who have a professional Doris B. Nathan, Secretary degree in architecture from a U.S. -

CTA-E-BROCHURE.Pdf

About Us CTA Architects P.C. offers a wide range of architectural services for urban living. Established in 1987, we have worked primarily on large buildings. We specialize in new design, restoration, rehabilitation, interior design, affordable housing and historic preservation. We have an excellent reputation for being trustworthy and thorough. Architectural Record has recognized us as one of the top 300 architecture firms in the country for 2016 and 2017. Our key personnel are directly involved in every project. Through our team approach and commitment to training, each staff member has an extensive knowledge of design, materials and technology, and benefits from a stimulating and creative environment. Our low employee turnover rate enables us to meet the high standards our clients have come to expect. Bronx Charter School for Excellence 3 IS 187K 1. Design 2. Historic Preservation 3. Exterior Restoration Contents 08-11 BRONX CHARTER SCHOOL FOR EXCELLENCE 48-49 36 GRAMMERCY PARK EAST 88-89 GOUVENEUR COURT 12-13 BALMAIN NEW YORK FLAGSHIP STORE 50-53 JAFFE ART THEATER INTERIOR 90-91 230 RIVERSIDE DRIVE 14-15 308 EAST 30TH STREET 54-55 JAFFE ART THEATER EXTERIOR 92-95 IRISH HUNGER MEMORIAL 16-17 17 PITT STREET 56-57 CHEROKEE APARTMENTS 96-97 I.S. 187K 18-19 GRAND STREET REHABILITATION 58-59 18 EAST 82ND STREET 98-99 MORNINGSIDE GARDENS TH 20-21 300 CENTRAL PARK WEST 60-61 CHAPEL OF THE SISTERS 100-101 900 5 AVENUE 22-23 LOWER EASTSIDE GIRLS CLUB 62-63 PROSPECT CEMETERY 102-103 SILVER TOWERS 24-25 ARABELLA 101 64-65 ST. -

Slices of “The Big Apple” This Is New York City

Slices of “The Big Apple” This is New York City An anthology of Wit, Reflections & Amusements Cliff Strome Licensed NYC Private Tour Guide 1 Slices of “The Big Apple” This is New York City An anthology of Wit, Reflections & Amusements Cliff Strome Licensed NYC Private Tour Guide 2 Cliff Strome, is a Licensed New York City Guide, recipient of The City of New York Dept. of Consumer Affairs highest rating, nominated Best Private NYC Tour Guide by The Association of New York Hotel Concierges (2011 and 2014), awarded The TripAdvisor Certificate of Excellence (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 & 2017,). Cliff has achieved the highest percentage of five star reviews (Excellent) on TripAdvisor, at the rate of 99% based on over 500 reviews. [email protected] www.customandprivate.com Cliff Strome 382 Central Park West New York, NY 10025 212-222-1441 March 2018 3 For Aline My wife, my candle, the light of my life. 4 Table of Slices Introduction 8 Chapter I “No! You Go!” 9 The Legally Blind Woman 17 “Can’t Go To Motor Vehicle Without a Pen!” 14 Dr. Bartha vs. Big Bertha 20 Acts of Kindness, a 1,000 Minute 27 “I’m one of the Owners” 32 “They Better Not!” 37 220 Central Park South 40 Chapter II My Playbook 1 in 8,300,000 45 “Friend of the House” 51 Singles “Seen” 57 One of These Glasses is Not Like the Other 70 A Tree Doesn’t Grow in Central Park 75 “I Got Interests on Both Sides” 78 “Instant Funship” 96 The 47th St. -

Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 1 of 22

Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 1 of 22 Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: DISTRICT OF DELAWARE Case number (if known) Chapter 11 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 4/19 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name iPic Media LLC 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed DBA See Rider 1 names, trade names and doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 61-1740150 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 433 Plaza Real, Suite 335 Boca Raton, FL 33432 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Palm Beach Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) www.ipic.com 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy page 1 Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 2 of 22 Debtor iPic Media LLC Case number (if known) Name 7. -

Waterfront Plan Appendices

A.1 Appendix 1: Community Participation Alexandria Waterfront Small Area Plan Community Participation: Outreach Activities The outreach activities for the Waterfront Small Area Plan (Plan) began in April 2009 and continue to the present. The outreach program has been multi- faceted and extensive, with a variety of activities, including tours, meetings, and charrettes that have promoted access to information and involvement in the process. Additionally, different outreach tools such as eNews and the waterfront webpage are being utilized to help citizens and other interested stakeholders keep abreast of activities and stay involved. The Plan and information generated at various activities can be downloaded from the webpage at www. alexandriava/Waterfront. The City is committed to continuing this level of community outreach throughout the public review process for the Plan and its implementation. The following pages discuss the iterative community process which led to the draft Plan, beginning with: (1) Early Outreach Activities; (2) Ideas and Guiding Concepts; (3) Activity Map; (4) Goals and Objectives; (5) Concept Plan; (6) Core Area Draft Design; and (7) the Plan. Alexandria Waterfront Small Area Plan Table A1: Early Outreach Activities Community Participation: Early Outreach Activities from April 2009 to April 2010 Presentation of schedule and an “open mike” Community Forum #1 - April 23, 2009 solicitation of themes from stakeholder organizations and individuals. Introduction of consultants and sub- Community Forum #2 – April 30, 2009 consultants; discussion of best practices and examples of waterfronts from around the world. View of the entire Alexandria Waterfront from the water with background information on the Boat Tour – May 30, 2009 history of the Waterfront and identification of key places along the Waterfront. -

The City Record

VOLUME CXLI NUMBER 75 FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 2014 Price: $4.00 Health and Hospitals Corporation . .1383 Housing Authority . .1383 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Supply Management � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �1383 Human Resources Administration . .1384 BILL DE BLASIO PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Mayor Agency Chief Contracting Officer � � � � � �1384 Borough President - Brooklyn �������������������1365 Contracts� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �1384 Borough President - Queens . .1365 STACEY CUMBERBATCH City Council . .1366 Information Technology and Commissioner, Department of Citywide City Planning Commission . .1376 Telecommunications. .1384 Administrative Services Parks and Recreation ���������������������������������1384 Information Technology and ELI BLACHMAN Telecommunications. .1377 Capital Projects � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �1384 Editor, The City Record Landmarks Preservation Commission . .1377 Revenue and Concessions � � � � � � � � � � � � �1385 Office of The Mayor . .1379 Police �����������������������������������������������������������1385 Published Monday through Friday, except Transportation �������������������������������������������1379 Contract Administration � � � � � � � � � � � � �1385 legal holidays by the New York City Public Library/Queens �������������������������������1385 PROPERTY DISPOSITION Department of Citywide Administrative Teachers’ Retirement System . .1385 Services under Authority of Section 1066 of Citywide Administrative Services �������������1380 Transportation �������������������������������������������1385 -

News and Comment of City and Suburban Real Estate Market

News and Comment of City and Suburban Real Estate Market f-!- Mistakes in Home Building r.:-'.'-¡Builders Are Hard At Adds 55 Mow Acres T.umber Priées Demand for Land Investors Continue to Show Can Be Avoided It in Many Sections To Mountain Ridge Have Had Big Greatest Since War A general resumption of build¬ (Huh in Year WÜOR the first time since before Interest in East Side Easily ing activities on a fairly large Country Links Drop Flats scale and in all parts of the coun¬ the start of the World War try is indicated by the volume of there is n strong demand for land Plan With Care and Sufficient Detail to Allow applications from building con¬ West Orange Organization Comparative Figures Show! In the suburbs for residential de¬ Most of the Announced tractors for construction loans re¬ Plans to Erect New Club¬ Now Are Buying Yesterday Was of Contractor to Estimate Cost More Accurately ; ceived during the last fortnight by Quotation* 30j velopment. In the last three weeks Tenements in This Both in tho Commonwealth Finance Cor¬ house to Cost to 75 Per Cent Under! we have Hold a number of parcel« Section, Upper Will Know Then What to Eliminate poration, 100 Broadway. $150,000, "From Besides Other Those of Last in the vicinity of Greenwich for Im¬ and Lower Districts of Manhattan Providence, R. I., to Kan¬ Changes September with homes. sas City, Mo., clear across the cen¬ mediate development By Clarence'-O. Baring done manually only a few years ago. tral country, business is on the The Mountain Wholesale lumber here have "In our opinion, this confirms the Martha H. -

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation By Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Samuel H. K ress Mid-Career G rant Study Funded by The James Marston Fitch Charitable Foundation 2010 Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Landmark Beginnings: The Advisory Commission (1962-1965) 5 Chapter 2 The Commission Established (1965-1973) 28 Chapter 3 Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983) 55 Chapter 4 The Commission Under Siege (1983-1990) 91 Chapter 5 The Commission Comes of Age: Growth and Maturity (1990-1990) 110 Epilogue 129 Acknowledgments 135 IN T R O DU C T I O N Historic preservation as an officially mandated government program has been existence for almost fifty years in New York City, but the history of the movement, both before and after the ratification and implementation of the Landmarks law, has been largely undocumented until relatively recently. Giving Preservation a History: Histories of Historic Preservation in the United States and Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks are part of an effort to rectify that situation.1 This work, told partly from my personal perspective, covers part of the story told by Anthony C. Wood and carries it forward to the end of the twentieth century. It describes and analyzes the history of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission while setting it within a larger national context. New York had been preceded by several other American cities, including Charleston, South Carolina, New Orleans, and Boston, in the establishment of a local preservation law and an accompanying oversight body, but still it had few models to emulate. -

Memories of Doty Island a Link Between Two Cities

Memories of Doty Island A Link Between Two Cities I Edited by Caryl Chandler Herzigcr Winifred Anderson Pawlovvski Memories of Doty Island A Link Between Two Cities COMPLIMENTS or mi: MENASHA AND NEENAH HISTORICAL SOCIETIES island Doty of Map 167? Memories of Doty Island A Link Between Two Cities Edited by Caryl Chandler Herziger Winifred Anderson Pawlowski Printed in U.S.A. 1 999 SPECIAL RECOGNITION SHOULD BE GIVEN TO MOWRY SMITH, WHO INITIATED AND SUPPORTED THE WRITING OF THIS BOOK. Caver fihofo: Dmiv Cabin, circa 1850 . Table of Contents List of illustrations . vi Acknowledgements . , vii To The Reader ............... viii Progression of Doty Island , I Trails and Roads , . .......... 6 Growing Up on Doty Island I : Early Settlers ....... H r . 1 5 Bridges and Waterways 29 Residents ............ f .... r ... 3? Special Buildings Neighborhood Stores .................... 70 Commercial Street Businesses 76 Washington Street 96 Industries 102 Churches .......... , ....... 128 Schools 136 Health ........ .&. ................... 145 Parks . MS Entertainment ......................... 153 Crimes ..... 168 Epilogue ........... * ... T .............. 1 71 . List of Illustrations 1 l 187/ VI ap of Doty Island ...... front ispiccc 2. James Duane Doty is 3. West en d of Miculet Boulevard ........ 7 4. Residence of E. L. Mathewson ........ 23 J. Residence of A. J. Webster 27 6. First Mill Street bridge ............... 31 7. Home of S. A. Cook 39 8, Residence of A. H. F, Krueger ........ 47 9, Home of George A, Whiting 55 10. S. A, Cook Armory 59 1 1 . Roberts' Resort „ .... , 67 12. Map of area formerly called ”Dog Town” 73 13. Louts Herziger Meats , . 77 14. John Strip Grocery . S3 15. Hart Hotel ;<[. -

Copyrighted Material

16_763969_bindex.qxd 2/22/06 11:03 AM Page 441 ACCOMMODATION INDEX 60 Thompson, 61, 103 Crowne Plaza United Nations, 89 70 Park Avenue Hotel, 103 Days Inn hotels, 62 Akwaaba Mansion, 86 DoubleTree Guest Suites Times Square, 90 Alex Hotel, The, 86 DoubleTree Metropolitan, 90 Algonquin Hotel, The, 56, 86 downtown hotels (list), 83 Ameritania Hotel, 87 Drake Swissôtel, The, 90 Avalon, 56, 61, 87 Dream, 91 Dylan Hotel, 91 Barclay New York, 58, 87 Bed-and-Breadfast on the Park, 86 Embassy Suites NYC, 91 Beeman Tower Hotel, 55, 86 Essex House Motel Nikko New York, 54, 90 Benjamin Hotel, 56, 86 Excelsior, 90 Bentley, 56, 87 Best Western Gregory, 62 Fitzpatrick Grand Central, 61, 90 Blakely, 54, 87 Fitzpatrick Manhattan Hotel, 91 Blue Moon Hotel, 47, 60, 87 Flatotel International, 54, 58, 91 Brooklyn hotels, 84 Four Points by Sheraton Manhattan Chelsea, 91 Bryant Park Hotel, 88 Four Seasons Hotel, 54, 56, 58, 92 Franklin, The, 56, 92 Carlton, The, 88 Carlyle, The, 54, 62, 88 Gramercy Park hotels, 83–84 Chambers-a Hotel, 89 Grand Hyatt New York, 54, 55, 92 Chelsea hotels,COPYRIGHTED 83–84 MATERIAL Chelsea Savoy, 61, 89 Habitat, 65 City Club Hotel, 89 Harbor House, 93 Clarion Fifth Avenue, 88 Harbor House Bed & Breakfast, 47 Comfort Inn Long Island City, 62 Harlem hotels, 84 Cosmopolitan Hotel, 88 Harlem Landmark Guest House, 47 Country Inn by the City, 88 Hilton Garden Inn, 62 Couryard by Marriott, 89 Hilton Times Square, 93 Crowne Plaza Manhattan, 55, 89 Holiday Inn Express Queens, 62 16_763969_bindex.qxd 2/22/06 11:03 AM Page 442 442 INDEX Holiday