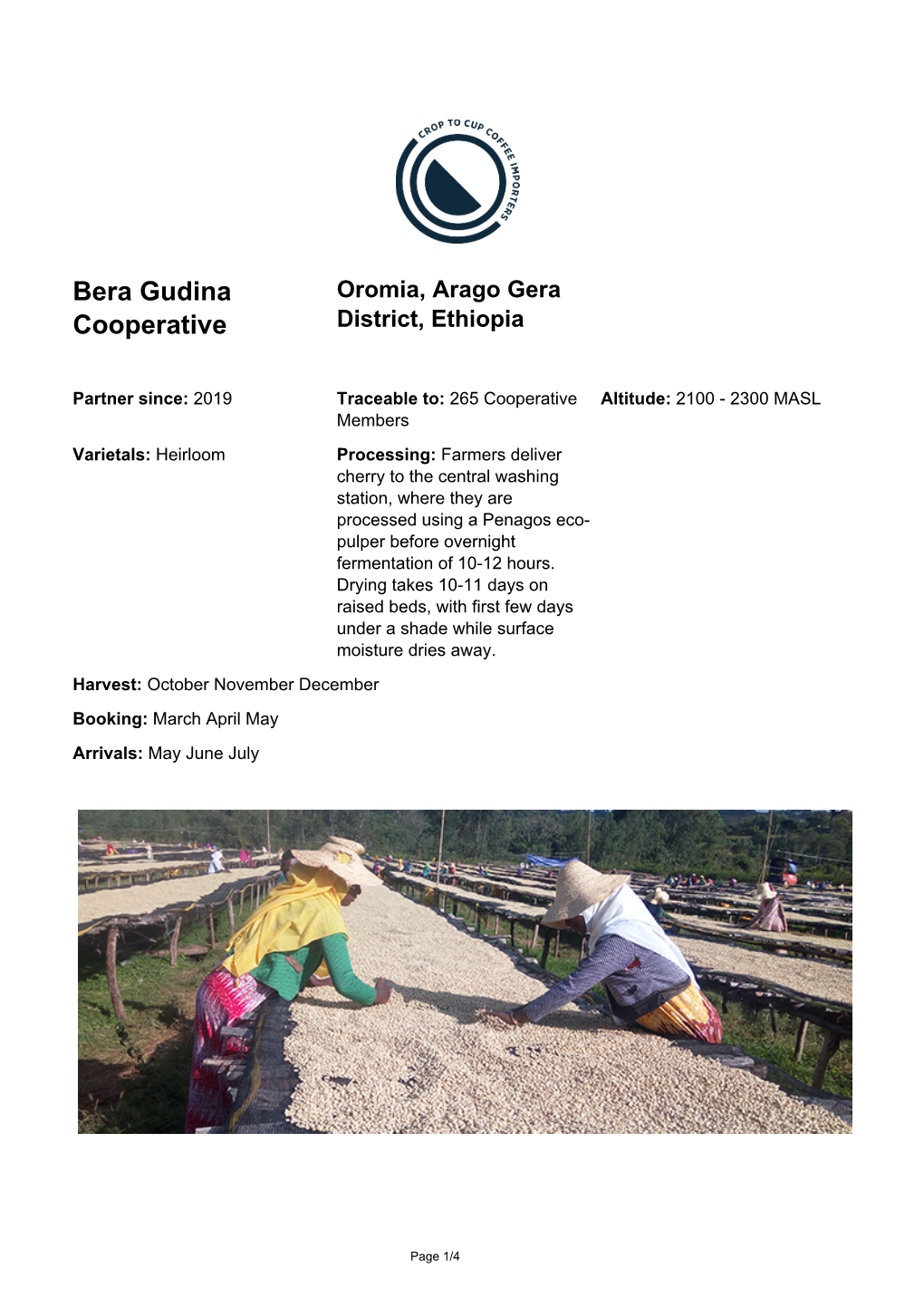

Bera Gudina Cooperative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Situational Analysis of Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: the Case of Jimma and Agaro Towns of Oromia Regional State

European Scientific Journal September 2014 edition vol.10, No.26 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE AND EXPLOITATION: THE CASE OF JIMMA AND AGARO TOWNS OF OROMIA REGIONAL STATE Gudina Abashula Nega Jibat Jimma University, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Department of Sociology and Social Work Abstract This study was conducted to assess people’s awareness, patterns, community responses and factors for child sexual abuse and exploitation in Jimma and Agaro town. Survey, key informant interview and case studies were used to collect the information required for the study. The data collected was analyzed using percentages and case studies under themes developed based on the research objectives. The findings of the study revealed that eighty nine percent of the respondents are aware of the existence of child sexual abuse in their community and more than half of them have identified sexual intercourse with children, child pornography and child genital stimulation as child sexual abuses. Both girls and boys can be exposed to child sexual abuse; however, girls are more vulnerable to child sexual abuses than boys. In terms of their backgrounds, street children, orphans and children of the poor families are mainly vulnerable to child sexual abuse. Children are sexually abused in their home, in the community and in organizations as the findings from the case studies and key informant interviews indicated. Death of parents, family poverty and the subsequent inability to fulfill the necessary basic needs for children; abusers’ perception about sexual affairs with children is safe as they think children are free from HIV/AIDS, lack of appropriate care and follow up for children are the major factors for child sexual abuse. -

Challenges of Clinical Chemistry Analyzers Utilization in Public Hospital Laboratories of Selected Zones of Oromia Region, Ethiopia: a Mixed Methods Study

Research Article ISSN: 2574 -1241 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2021.34.005584 Challenges of Clinical Chemistry Analyzers Utilization in Public Hospital Laboratories of Selected Zones of Oromia Region, Ethiopia: A Mixed Methods Study Rebuma Belete1*, Waqtola Cheneke2, Aklilu Getachew2 and Ahmedmenewer Abdu1 1Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia 2School of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Institute of Health, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Rebuma Belete, Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: March 16, 2021 Background: The modern practice of clinical chemistry relies ever more heavily on automation technologies. Their utilization in clinical laboratories in developing countries Published: March 22, 2021 is greatly affected by many factors. Thus, this study was aimed to identify challenges affecting clinical chemistry analyzers utilization in public hospitals of selected zones of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Citation: Rebuma Belete, Waqtola Cheneke, Aklilu Getachew, Ahmedmenew- Methods: A cross-sectional study using quantitative and qualitative methods er Abdu. Challenges of Clinical Chemistry was conducted in 15 public hospitals from January 28 to March 15, 2019. Purposively Analyzers Utilization in Public Hospital selected 68 informants and 93 laboratory personnel working in clinical chemistry section Laboratories of Selected Zones of Oromia were included in the study. Data were collected by self-administered questionnaires, Region, Ethiopia: A Mixed Methods Study. in-depth interviews and observational checklist. The quantitative data were analyzed Biomed J Sci & Tech Res 34(4)-2021. by descriptive statistics using SPSS 25.0 whereas qualitative data was analyzed by a BJSTR. -

Historical Survey of Limmu Genet Town from Its Foundation up to Present

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 6, ISSUE 07, JULY 2017 ISSN 2277-8616 Historical Survey Of Limmu Genet Town From Its Foundation Up To Present Dagm Alemayehu Tegegn Abstract: The process of modern urbanization in Ethiopia began to take shape since the later part of the nineteenth century. The territorial expansion of emperor Menelik (r. 1889 –1913), political stability and effective centralization and bureaucratization of government brought relative acceleration of the pace of urbanization in Ethiopia; the improvement of the system of transportation and communication are identified as factors that contributed to this new phase of urban development. Central government expansion to the south led to the appearance of garrison centers which gradually developed to small- sized urban center or Katama. The garrison were established either on already existing settlements or on fresh sites and also physically they were situated on hill tops. Consequently, Limmu Genet town was founded on the former Limmu Ennarya state‘s territory as a result of the territorial expansion of the central government and system of administration. Although the history of the town and its people trace many year back to the present, no historical study has been conducted on. Therefore the aim of this study is to explore the history of Limmu Genet town from its foundation up to present. Keywords: Limmu Ennary, Limmu Genet, Urbanization, Development ———————————————————— 1. Historical Background of the Study Area its production. The production and marketing of forest coffee spread the fame and prestige of Limmu Enarya ( The early history of Limmu Oromo Mohammeed Hassen, 1994). The name Limmu Ennarya is The history of Limmu Genet can be traced back to the rise derived from a combination of the name of the medieval of the Limmu Oromo clans, which became kingdoms or state of Ennarya and the Oromo clan name who settled in states along the Gibe river basin. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

The Effect of Global Coffee Price Changes on Rural Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia

The Effect of Global Coffee Price Changes on Rural Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia A Case Study from Jimma Area Aklilu Amsalu, with Eva Ludi NCCR North-South Dialogue, no. 26 2010 The present study was carried out at the following partner institutions of the NCCR North-South: Overseas Development Institution (ODI) London, UK Department of Geography & Environmental Studies Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia Regional Coordination Office, JACS East Africa Addis Abeba, Ethiopia Swisspeace Bern, Switzerland The NCCR North-South (Research Partnerships for Mitigating Syndromes of Global Change) is one of twenty National Centres of Competence in Research established by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). It is implemented by the SNSF and co- funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions in Switzerland. The NCCR North-South carries out disciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research on issues relating to sustainable development in developing and transition countries as well as in Switzerland. http://www.north-south.unibe.ch The Effect of Global Coffee Price Changes on Rural Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia A Case Study from Jimma Area Aklilu Amsalu, with Eva Ludi NCCR North-South Dialogue, no. 26 2010 Citation Aklilu Amsalu, Ludi E. 2010. The Effect of Global Coffee Price Changes on Rural Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia: A Case Study from Jimma Area. NCCR North-South Dialogue 26. Bern, Switzerland: NCCR North-South. Editing Stefan Zach, z.a.ch gmbh, Switzerland Cover photos Left: Typical landscape in the Jimma area – a mosaic of coffee forests and crop land. -

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

Integrating Food Security and Biodiversity Governance a Multi

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326632264 Integrating food security and biodiversity governance: A multi-level social network analysis in Ethiopia Article in Land Use Policy · July 2018 DOI: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.07.014 CITATION READS 1 133 4 authors: Tolera Senbeto Jiren Arvid Bergsten Leuphana University Lüneburg Leuphana University Lüneburg 5 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 15 PUBLICATIONS 122 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Julia Leventon Joern Fischer Leuphana University Lüneburg Leuphana University Lüneburg 38 PUBLICATIONS 483 CITATIONS 220 PUBLICATIONS 13,108 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Wood-pastures of Transylvania (Romania). View project Is informal labor sharing among smallholders influencing their food security and crop-choice sovereignty? View project All content following this page was uploaded by Tolera Senbeto Jiren on 09 August 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Land Use Policy 78 (2018) 420–429 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Land Use Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol Integrating food security and biodiversity governance: A multi-level social network analysis in Ethiopia T ⁎ Tolera Senbeto Jiren , Arvid Bergsten, Ine Dorresteijn, Neil French Collier, Julia Leventon, Joern Fischer Leuphana University, Faculty of Sustainability, Scharnhorststrasse 1, D21335 Luneburg, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Integrating food security and biodiversity conservation is an important contemporary challenge. Traditionally, Biodiversity food security and biodiversity conservation have been considered as separate or even incompatible policy goals. Food security However, there is growing recognition of their interdependence, as well as of the need to coordinate solutions Governance across multiple policy sectors and levels of governance. -

Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia a M Tigray a Afar M H U Amhara a Uz N M

35°0'0"E 40°0'0"E Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia A m Tigray A Afar m h u Amhara a uz N m Dera u N u u G " / m r B u l t Dire Dawa " r a e 0 g G n Hareri 0 ' r u u Addis Ababa ' n i H a 0 Gambela m s Somali 0 ° b a K Oromia Ü a I ° o A Hidabu 0 u Wara o r a n SNNPR 0 h a b s o a 1 u r Abote r z 1 d Jarte a Jarso a b s a b i m J i i L i b K Jardega e r L S u G i g n o G A a e m e r b r a u / K e t m uyu D b e n i u l u o Abay B M G i Ginde e a r n L e o e D l o Chomen e M K Beret a a Abe r s Chinaksen B H e t h Yaya Abichuna Gne'a r a c Nejo Dongoro t u Kombolcha a o Gulele R W Gudetu Kondole b Jimma Genete ru J u Adda a a Boji Dirmeji a d o Jida Goro Gutu i Jarso t Gu J o Kembibit b a g B d e Berga l Kersa Bila Seyo e i l t S d D e a i l u u r b Gursum G i e M Haro Maya B b u B o Boji Chekorsa a l d Lalo Asabi g Jimma Rare Mida M Aleltu a D G e e i o u e u Kurfa Chele t r i r Mieso m s Kegn r Gobu Seyo Ifata A f o F a S Ayira Guliso e Tulo b u S e G j a e i S n Gawo Kebe h i a r a Bako F o d G a l e i r y E l i Ambo i Chiro Zuria r Wayu e e e i l d Gaji Tibe d lm a a s Diga e Toke n Jimma Horo Zuria s e Dale Wabera n a w Tuka B Haru h e N Gimbichu t Kutaye e Yubdo W B Chwaka C a Goba Koricha a Leka a Gidami Boneya Boshe D M A Dale Sadi l Gemechis J I e Sayo Nole Dulecha lu k Nole Kaba i Tikur Alem o l D Lalo Kile Wama Hagalo o b r Yama Logi Welel Akaki a a a Enchini i Dawo ' b Meko n Gena e U Anchar a Midega Tola h a G Dabo a t t M Babile o Jimma Nunu c W e H l d m i K S i s a Kersana o f Hana Arjo D n Becho A o t -

Factors Affecting Social Accountability in Service Providing Public Sectors: Exploring Beneficiaries' Perspectiv Es in Jimma Z

Research, Society and Development ISSN: 2525-3409 ISSN: 2525-3409 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Itajubá Brasil Factors Affecting Social Accountability in Service Providing Public Sectors: Exploring Beneficiaries’ Perspectiv es in Jimma Zone Doja, Hunde; Duressa, Tadele Factors Affecting Social Accountability in Service Providing Public Sectors: Exploring Beneficiaries’ Perspectiv es in Jimma Zone Research, Society and Development, vol. 8, no. 12, 2019 Universidade Federal de Itajubá, Brasil Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=560662203013 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v8i12.1571 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Factors Affecting Social Accountability in Service Providing Public Sectors: Exploring Beneficiaries’ Perspectiv es in Jimma Zone Fatores que afetam a responsabilidade social nos setores prestadores de serviços: explorando as perspectivas dos beneficiários na zona de Jimma Factores que afectan la responsabilidad social en la prestación de servicios a sectores públicos: exploración de las perspectivas de los beneficiarios en la zona de Jimma Hunde Doja [email protected] Jimma University, Etiopía hp://orcid.org/0000-0002-1559-6252 Tadele Duressa [email protected] Jimma University, Etiopía Research, Society and Development, vol. 8, no. 12, 2019 hp://orcid.org/0000-0002-8663-1027 Universidade Federal de Itajubá, Brasil Received: 29 August 2019 Revised: 31 August 2019 Accepted: 25 September 2019 Abstract: is study was undertaken to identify the factors affecting social Published: 27 September 2019 accountability in service providing public sector organizations from beneficiary DOI: https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd- perspectives in Jimma Zone. -

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (August 2017)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (August 2017) ERITREA National capital P Erob Tahtay Adiyabo Regional capital Gulomekeda Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Ahferom Red Sea Humera Adigrat ! ! Dalul ! Adwa Ganta Afeshum Aksum Saesie Tsaedaemba Shire Indasilase ! Zonal Capital ! North West TigrayTahtay KoraroTahtay Maychew Eastern Tigray Kafta Humera Laelay Maychew Werei Leke TIGRAY Asgede Tsimbila Central Tigray Hawzen Medebay Zana Koneba Naeder Adet Berahile Region boundary Atsbi Wenberta Western Tigray Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele Zone boundary Tanqua Abergele P Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Tsegede Tselemt Mekele Town Special Enderta Afdera Addi Arekay South East Ab Ala Tsegede Mirab Armacho Beyeda Woreda boundary Debark Erebti SUDAN Hintalo Wejirat Saharti Samre Tach Armacho Abergele Sanja ! Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Addis Ababa Ziquala Maychew ! Wegera Metema Lay Armacho Wag Himra Endamehoni Raya Azebo North Gondar Gonder ! Sekota Teru Afar Chilga Southern Tigray Gonder City Adm. Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Gaz Gibla Zone 4 (Fantana Rasu ) Elidar Amhara Gelegu Quara ! Takusa Ebenat Gulina Bugna Awra Libo Kemkem Kobo Gidan Lasta Benishangul Gumuz North Wello AFAR Alfa Zone 1(Awsi Rasu) Debre Tabor Ewa ! Fogera Farta Lay Gayint Semera Meket Guba Lafto DPubti DJIBOUTI Jawi South Gondar Dire Dawa Semen Achefer East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Delanta Habru Asayita P Tach Gayint ! Bahir Dar City Adm. Aysaita Guba AMHARA Dera Ambasel Debub Achefer Bahirdar Zuria Dawunt Worebabu Gambela Dangura West Esite Gulf of Aden Mecha Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Simada Thehulederie Kutaber Dangila Yilmana Densa Afambo Mekdela Tenta Awi Dessie Bati Hulet Ej Enese ! Hareri Sayint Dessie City Adm. -

Study on Rumen and Reticulum Foreign Bodies in Cattle Slaughtered at Jimma Municipal Abattoir, South West Ethiopia

American-Eurasian Journal of Scientific Research 7 (4): 160-167, 2012 ISSN 1818-6785 © IDOSI Publications, 2012 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejsr.2012.7.4.65140 Study on Rumen and Reticulum Foreign Bodies in Cattle Slaughtered at Jimma Municipal Abattoir, South West Ethiopia Desiye Tesfaye and Mersha Chanie University of Gondar, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Paraclinical Studies, P.O.Box, 196. Gondar, Ethiopia Abstract: A cross-sectional study was conducted from October, 2011 to March, 2012 at Jimma Municipal Abattoir, Oromia Regional State, Southwest Ethiopia, with the objectives of to assess the prevalence of rumen and reticulum foreign bodies, identifying types of foreign bodies and associated risk factors for the occurrences of foreign bodies. Postmortem examination was employed for the recovery of foreign body from rumen and reticulum. The investigation was carried out in the abattoir. From total of 484 (464 male and 20 female) cattle were examined, 13.22 %( n=64) were found foreign bodies at slaughter. When the prevalence was compared between sex, between breed, among different age groups, among different body condition score and animal originated from different areas, higher prevalence of foreign bodies 80%, 70%,80%,72.72%,25.23% were observed in female, cross breed, age older than 10 years, animal having poor body condition score and animal originate from Agaro, respectively. These aforementioned factors are considered as potential risk factors and found highly significantly associated (p < 0.05) with the occurrence of foreign bodies. Rumen harbored mostly plastic materials while reticulum was the major site for the retention of metallic objects. Plastics were recovered as the most common foreign bodies followed by leathers, clothes, ropes, nails and wires.