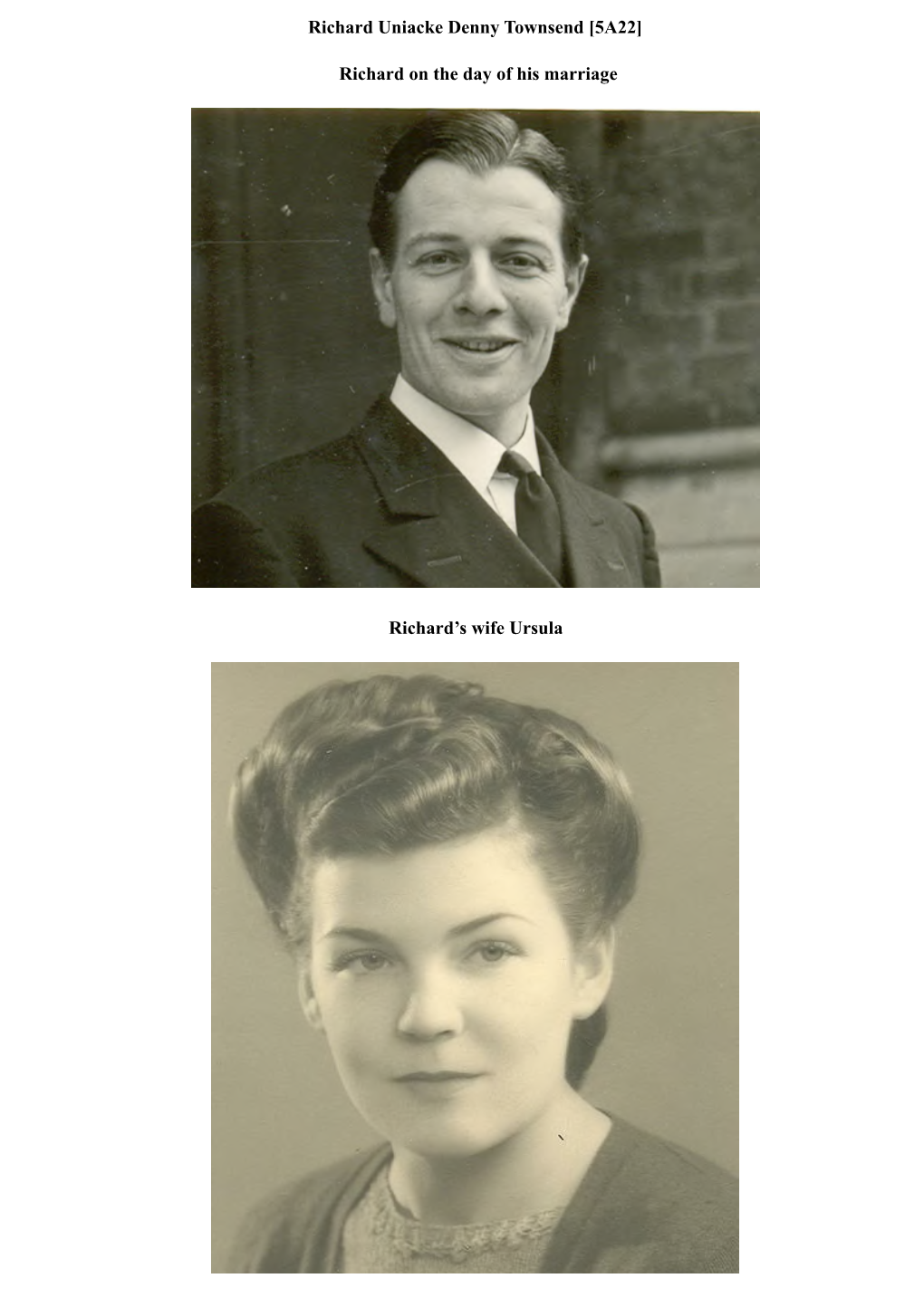

Richard Uniacke Denny Townsend [5A22]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUB. 143 Sailing Directions (Enroute)

PUB. 143 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ WEST COAST OF EUROPE AND NORTHWEST AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2014 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2014 FIFTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface date of the publication shown above. Important information to amend material in the publication is updated as needed and 0.0 Pub. 143, Sailing Directions (Enroute) West Coast of Europe available as a downloadable corrected publication from the and Northwest Africa, Fifteenth Edition, 2014 is issued for use NGA Maritime Domain web site. in conjunction with Pub. 140, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) North Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Seas. Companion 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website volumes are Pubs. 141, 142, 145, 146, 147, and 148. http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal 0.0 Digital Nautical Charts 1 and 8 provide electronic chart 0.0 coverage for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 4 October 2014, manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a including Notice to Mariners No. 40 of 2014. Subsequent course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- updates have corrected this publication to 24 September 2016, igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the including Notice to Mariners No. -

Société Des Régates De Douarnenez, Europe Championship Application

Société des Régates de Douarnenez, Europe championship Application Douarnenez, an ancient fishing harbor in Brittany, a prime destination for water sports lovers , the land of the island, “Douar An Enez” in Breton language The city with three harbors. Enjoy the unique atmosphere of its busy quays, wander about its narrows streets lined with ancient fishermen’s houses and artists workshops. Succumb to the charm of the Plomarch walk, the site of an ancient Roman settlement, visit the Museum Harbor, explore the Tristan island that gave the city its name and centuries ago was the lair of the infamous bandit Fontenelle, go for a swim at the Plage des Dames, “the ladies’ beach”, a stone throw from the city center. The Iroise marine park, a protected marine environment The Iroise marine park is the first designated protected marine park in France. It covers an area of 3500 km2, between the Islands of Sein and Ushant (Ouessant), and the national maritime boundary. Wildlife from seals and whales to rare seabirds can be observed in the park. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez, 136 years of passion for sail. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez was founded in 1883, and from the start competitive sailing has been a major focus for the club. Over many years it has built a strong expertise in the organization of major national and international events across all sailing series. sr douarnenez, a club with five dynamic poles. dragon dinghy sailing kiteboard windsurf classic yachting Discovering, sailing, racing Laser and Optimist one Practicing and promoting Sailing and promoting the Preserving and sailing the Dragon. -

Press Pack Bretagne

2021 PRESS PACK BRETAGNE brittanytourism.com | CONTENTS Editorial p. 03 Slow down Take your foot off the pedal p. 04 Live Experience the here and now p. 12 Meet Immerse yourself in local culture p. 18 Share Together. That’s all ! p. 24 Practical information p. 29 EDITORIAL Bon voyage 2020 has been an unsettling and air and the wide open spaces. Embracing with the unexpected. A concentration of challenging year and we know that many the sea. Enjoying time with loved ones. the essential, and that’s why we love it! It of you have had to postpone your trip to Trying something new. Giving meaning to invites you to slow down, to enjoy life, to Brittany. These unusual times have been our daily lives. Meeting passionate locals. meet and to share: it delivers its promise a true emotional rollercoaster. They Sharing moments and laughs. Creating of uniqueness. So set sail, go for it, relax have also sharpened our awareness and memories for the years to come. and enjoy it as it comes. Let the eyes do redesigned our desires. We’re holding on to Let’s go for an outing to the Breton the talking and design your next holiday our loved ones, and the positive thoughts peninsula. A close, reassuring destination using these pages. of a brighter future. We appreciate even just across the Channel that we think we We wish you a wonderful trip. more the simple good things in life and know, but one that takes us far away, on the importance of seizing the moment. -

Publicité Préfecture

DU FINISTERE Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer du Finistère Publicité des demandes d'autorisation d'exploiter pour mise en valeur agricole enregistrées par la Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer du Finistère au 09/04/2021 Conformément aux articles R331-4 et D331-4-1 du code rural et de la pêche maritime, la Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer du Finistère publie les demandes d'autorisations d'exploiter enregistrées ci-dessous : Date limite Date de dépôt d'enregist des Références cadastrales parcelle Superficie Propriétaires ou Mandataires Demandeur Cédant N°Dossier rement de demandes la concurrente demande s (dossier complet) IHUEL JEAN-LOUIS IHUEL EVELYNE ARZANO ZN11B - ZN11C - ZN11E - ZN31 3,3577 ha DENIS/JACQUELINE LUCIENNE 56400 BRECH C29210447 31/03/21 09/06/21 56620 PONT SCORFF 56620 PONT SCORFF E602 - E604 - E605 - E607 - E610 - F733A - LACHUER/GURVAN 29650 BOTSORHEL - EARL DE GOASBRIANT EARL DE GOASBRIANT BOTSORHEL 1,8058 ha C29210323 22/03/21 09/06/21 F733Z LACHUER/AMELIE 22780 PLOUGRAS 29610 PLOUIGNEAU 29610 PLOUIGNEAU F306 - F307 - F308 - F317 - F318A - F318Z - LACHUER/GURVAN 29650 BOTSORHEL - EARL DE GOASBRIANT EARL DE GOASBRIANT BOTSORHEL F319 - F320 - F321 - F331 - F332 - F342A - 5,5146 ha C29210323 22/03/21 09/06/21 LACHUER/AMELIE 22780 PLOUGRAS 29610 PLOUIGNEAU 29610 PLOUIGNEAU F342Z - F731A - F731Z - F732 LACHUER/GURVAN 29610 PLOUIGNEAU - EARL DE GOASBRIANT EARL DE GOASBRIANT BOTSORHEL F309 - F328A - F328B 1,0475 ha C29210323 22/03/21 09/06/21 LACHUER/AMELIE 29610 -

Fichier Entreprises Au 07 05 2021 Partenaires

Offres CFA Bâtiment de QUIMPER Tél : 02 98 95 97 26 [email protected] 07 Mai 2021 PLOUGONVELIN BAC PRO TISEC SAINT POL DE LEON BREST BP CARRELEUR MOSAISTE LE CLOITRE PLEYBEN QUIMPERLE FOUESNANT MOELAN SUR MER GOURLIZON BP COUVREUR PLOMELIN CHATEAULIN PLOUNEOUR TREZ CONCARNEAU NEVEZ BP ELEC CLOHARS CARNOET LE FAOU GUISSENY TELGRUC SUR MER ELLIANT PLOUGUERNEAU BP MACON PLUGUFFAN PONT CROIX BREST LANDERNEAU PLOUGONVEN PLESCOP BRIEC BANNALEC CLOHARS CARNOET PLONEVEZ DU FAOU BP MENUISIER GUISSENY CLEDER LOCMARIA BERRIEN QUIMPER GUILERS SAINT YVI PLABENNEC AUDIERNE CONCARNEAU BP PAR LE FAOUET GUIPAVAS HUELGOAT LANDERNEAU CHATEAUNEUF DU FAOU BREST QUIMPER PLABENNEC SAINT THEGONNEC PLEUVEN LE CLOITRE PLEYBEN CAP CARRELEUR MOSAISTE PLABENNEC QUIMPER EDERN PLABENNEC PENMARCH PONT L ABBE SAINT MARTIN DES CHAMPS LOPERHET GUENGAT PLOUARZEL ST POL DE LEON LANDIVISIAU GUILER SUR GOYEN QUIMPERLE CLEDER KERNILIS CAP CHARPENTIER BOIS SAINT DERRIEN PLOUIGNEAU PLONEOUR LANVERN LANDERNEAU CLEDER PLOUARZEL QUIMPER PLOEMEUR COBARM PONT CROIX CLEDER PLOUARZEL BENODET PLOUHINEC GUIPAVAS CONCARNEAU BREST CAP COUVREUR CROZON CLOHARS CARNOET CLEDEN POHER PLOUVIEN SAINT THURIEN PLOGONNEC GUICLAN PLUGUFFAN LANDIVISIAU TREGOUREZ GUENGAT TREGLONOU MILIZAC BREST PLOMELIN PLOMELIN FOUESNANT GOUESNOU PLOMELIN PLOUGUIN PLONEOUR LANVERN CHATEAULIN PLONEVEZ PORZAY BENODET ERGUE GABERIC PLOUZEVEDE KERLAZ CAP COUVREUR PLOUNEVEZ LOCHRIST ROSPORDEN CONCARNEAU GUICLAN PLOUEDERN PLOUGUIN PLOUNEOUR TREZ SCAER QUIMPERLE PLOUGOULM SCAER PLABENNEC PLONEOUR LANVERN ELLIANT -

Zones À Risque Particulier Vis-À-Vis De L'infection De L'avifaune Par Un Virus

Zones à risque particulier vis-à-vis de l'infection de l'avifaune par un virus Influenza aviaire hautement pathogène - FINISTERE (Arrêté du 16 novembre 2016 qualifiant le niveau de risque) NOM_DEPT INSEE_COMCommune ZONE A RISQUE PARTICULIER FINISTERE 29001 ARGOL RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29004 BANNALEC DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29005 BAYE DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29006 BENODET DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29011 BOHARS RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29015 BOURG-BLANC RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29016 BRASPARTS RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29019 BREST RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29020 BRIEC DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29021 BRIGNOGAN-PLAGES DPM : COTES D'ARMOR A Pte St MATHIEU FINISTERE 29022 CAMARET-SUR-MER RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29023 CARANTEC DPM : COTES D'ARMOR A Pte St MATHIEU FINISTERE 29026 CHATEAULIN RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29030 CLEDER DPM : COTES D'ARMOR A Pte St MATHIEU FINISTERE 29031 CLOHARS-CARNOET DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29032 CLOHARS-FOUESNANT DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29037 COMBRIT DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29039 CONCARNEAU DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29042 CROZON RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29043 DAOULAS RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29044 DINEAULT RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29045 DIRINON RADE DE BREST FINISTERE 29047 LE DRENNEC DPM : COTES D'ARMOR A Pte St MATHIEU FINISTERE 29048 EDERN DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29051 ERGUE-GABERIC DPM : Pte DE PENMARC'H AU MORBIHAN FINISTERE 29053 LE FAOU -

The Ero Vili and the Atlantic Wall

Advances in Anthropology, 2015, 5, 183-204 Published Online November 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2015.54018 The Ero Vili and the Atlantic Wall G. Tomezzoli, Y. Marzin European Patent Office, Munich, Germany Email: [email protected], [email protected] Received 17 August 2015; accepted 12 October 2015; published 15 October 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In this article the events concerning the south portion of the Audierne Bay in the department of Finistère (France) during the 2nd World War are analyzed. The role of the Ero Vili and the Camp Todt in the construction of the Atlantic Wall fortification and the state of preservation of the mili- tary and logistic constructions of this portion of the Audierne Bay are presented in order to sti- mulate further studies by experts and amateurs. Keywords 2nd World War, Atlantic Wall, Fortification, Bunkers, Audierne, France, Ero Vili 1. Introduction Located in the department of Finistère (France), at the west of Quimper, the Audierne Bay (47˚55'46''N, 4˚23'24''W) extends itself between the Point of Raz and the Point of Penmarch. Its south portion, low and sandy, between the Point of Penhors and the Point de la Torche, named beach of Tronoën, played, during the 2nd World War, a role of primary importance in the construction of the Atlantic Wall (Dupont & Peyle, 1994; Chazette, Destouches, & Paich, 1995; Duquesne, 1976; Lippmann, 1995; Rolf, 1988; Doaré & Le Berre, 2006). -

Molène Island

> MOLÈNE IN A FEW QUESTIONS... > PREPARE YOUR STAY • Prientit ho peaj > SHOPS AND RESTAURANTS • Stalioù-kenwerzh ha pretioù • Molenez gant un nebeud goulennoù www.pays-iroise.bzh and www.molene.fr Shops How to get here - General food store: 02 98 07 38 81 How does the island get its water supply? - Tobacconist’s, newspapers, souvenirs: 02 98 07 39 71 The island is now self-sufficient in its water management, thanks to two collective rainwater Departures all year from the following harbour stations: - Atelier des algues (seaweed workshop): 02 98 07 39 71 recovery supplies: the English water tank offered by Queen Victoria in 1896 and the - departures from Brest and Le Conquet by passenger ferry: 02 98 80 80 80 / www.pennarbed.fr - Les jardins de la Chimère (creation of jewellery): 02 98 07 37 32 impluvium built in 1976. We can also count 3 water catchments (ground water) located - departures from Le Conquet by individual taxi boats: 06 71 88 74 21 northwest of the island and private supplies, which are beginning to appear in many homes. During peak season from the following harbour stations: Warning: there is no ATM on the island. - departures from Camaret: 02 98 27 88 22 / www.pennarbed.fr Direct sale of fish and shellfish by the professional fishermen of Molène Is there a school on the island? - departures from Camaret, Lanildut and Le Conquet: 08 25 13 52 35 / www.finist-mer.fr - Berthelé Philippe (shellfish only): 06 32 71 26 75 From primary to secondary school, the children of Molène go to school on the island. -

Commissioned Report

COMMISSIONED REPORT Annex to Commissioned Report No. 271 A review of relevant experience of coastal and marine national parks Case studies (1 & 2) Parc Naturel Régional d’Armorique & Parc Naturel Marin d’Iroise - Brittany, France Prepared by Sue Wells for Hambrey Consulting This report should be cited as: Wells, S. (2008). Case studies 1 & 2 - Parc Naturel Régional d’Armorique and Parc Naturel Marin d’Iroise, Brittany, France. Scottish Natural Heritage Research, Annex to Commissioned Report No. 271 - Available online at http://www.snh.org.uk/strategy/CMNP/sr-adnp01.asp This report is one of a number of studies undertaken to inform the following publication: Hambrey Consulting (2008). A review of relevant experience of coastal and marine national parks. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 271 (ROAME No. R07NC). This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2008 Sketch profiles Parc Naturel Régional d’Armorique (PNRA) Location and size Includes four geographically defined areas of Finistere, northern Brittany: Ouessant-Molene archipelago (Ushant Islands); Crozon peninsula; Monts d’Arree; and estuary of the River Aulne. Total area 172,000 ha. Scope Primarily terrestrial, but includes 60,000 ha of marine water to 30 m depth (the marine area also falls within the proposed Parc Naturel Marin d’Iroise); other protected areas lie within its boundaries including the Reserve Biosphere d’Iroise and several terrestrial nature reserves. -

Sea & Shore Technical Newsletter

1 CENTRE OF DOCUMENTATION, RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTATION ON ACCIDENTAL WATER POLLUTION 715, Rue Alain Colas, CS 41836 - 29218 BREST CEDEX 2, FRANCE Tel: +33 (0)2 98 33 10 10 – Fax: +33 (0)2 98 44 91 38 Email: [email protected] - Web: www.cedre.fr Sea & Shore Technical Newsletter n°40 22001144---22 Contents • Spills ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Pollution in a port following failure of the dredger Prins IV (Port-Diélette, Manche, France) ............................ 2 Heavy fuel oil spill in a protected mangrove: collision of the Southern Star 7 (Bangladesh) ............................ 2 Heavy fuel oil spill in a port: the bulk carrier Lord Star (Brest, Brittany, France) ............................................... 5 Landslide and damage to the Tikhoretsk-Tuapse-2 pipeline (Black Sea, Russia) ............................................ 6 • Past spills ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Deepwater Horizon spill: BP agrees to pay out record-breaking compensation ............................................... 7 Environmental damages caused by the Exxon Valdez spill: an end to legal action for the US authorities ....... 7 • Review of spills having occurred worldwide in 2014 .................................................................. 7 Oil and HNS spills, all origins (Cedre analysis) ............................................................................................... -

Caf Du Finistère - Territoires D’Action Sociale

Caf du Finistère - Territoires d’action sociale Batz TERRITOIRE MORLAIX Roscoff Santec Brignogan St-Pol-de-Léon Plounéour-Trez Plouescat Sibiril Locquirec Kerlouan Cléder Plougasnou Plougoulm Guimaec TERRITOIRE Tréflez St-Jean- PONANT Guissény Carantec du-Doigt Plouguerneau Goulven Tréflaouénan Plounévez- Plouénan Plouézoc’h Henvic Lanmeur Landéda St-Frégant Plouider Lochrist Mespaul Locquénolé Kernouës Trézilidé Plouégat- St-Pabu St-Vougay Guérand Lannilis Kernilis Lesneven Taulé MORLAIX Lampaul- Plouzévédé Garlan Ploudalmézeau Le Folgoët Lanhouarneau Landunvez Tréglonou Plouvorn St-Martin- Lanarvily St-Méen Ploudalmézeau Plougar des-Champs Plouvien Trégarantec Plouigneau Plouégat- Plougourvest Plouguin Le Drennec St-Derrien Ste-Sève Moysan Plourin- Ploudaniel Guiclan Porspoder Ploudalmézeau Coat-Méal Le Ponthou ◄ Ouessant Tréouergat Plounéventer Bodilis Lanildut Bourg-Blanc Plabennec Trémaouézan Guipronvel Kersaint- St-Servais Landivisiau Pleyber- Guerlesquin Bréles Lanneuffret Plourin- Plabennec Christ les-Morlaix Lampaul- Lanrivoaré Plouédern St-Thégonnec Plouarzel Milizac St-Thonan Loc- Lampaul- Plougonven La Roche- EguinerGuimiliauGuimiliau Botsorhel Plouarzel Maurice St-Renan Gouesnou St-Divy Landerneau Ploudiry Lannéanou Bohars Guipavas Loc-Eguiner- Le Cloître- Guilers La Forêt- Pencran St-SauveurSt-Th. Landerneau La Martyre Locmélar St-Thégonnec Molène Ploumoguer Plounéour- Plouzané Ménez BREST Le Relecq- Dirinon Tréflévenez Bolazec Trébabu Kerhuon St-Urbain Scrignac Locmaria- Lopérhet Commana Plouzané Le Tréhou Le Conquet Sizun -

With DOL4DE4BRETAGNE 02 99 48 15 37 PONT4CROIX 02 98 70 40 38

Tourist information centres SB Sensation Bretagne Want to get back to Want to hunt out some of Brittany and Loire Atlantique SV Station Verte Bretagne Calling from abroad, add +33 before the number without “0” Nature ? heritage? Côtes d’Armor BREST 02 98 44 24 96 BRIEC4DE4L’ODET 02 98 57 74 62 BELLE4ISLE4EN4TERRE 02 96 43 01 71 BRIGNOGAN 02 98 83 41 08 Let the sea air recharge your batteries! Plunge right in and discover the medieval cities BINIC SB 02 96 73 60 12 CAMARET4SUR4MER 02 98 27 93 60 Discover the rich variety of landscapes in Brittany. Land of the sea Brittany’s historic past is best hunted on foot. You’ll fi nd it lurking BRÉHAT ÎLE 02 96 20 04 15 CARANTEC SB 02 98 67 00 43 (‘Armor’), Brittany has 2,700 km of coastal scenery: in fact, a third down a spiral stone staircase, quietly gleaming in a square CALLAC SV 02 96 45 59 34 CARHAIX4PLOUGUER 02 98 93 04 42 of the French coastline is in Brittany! You’ll love the constantly surrounded by half-timbered houses, or tucked away behind a gap CHÂTELAUDREN 02 96 79 77 71 CHÂTEAULIN 02 98 86 02 11 changing views, sometimes up close and personal, sometimes in the city walls. As you stroll the little back streets in Brittany’s many DINAN 02 96 87 69 76 CHATEAUNEUF4DU4FAOU 02 98 81 83 90 distant and majestic: cliff s, coves, dunes, sandy beaches – Brittany ‘Small Towns of Character’ (‘Petites Cités de Caractères’) and ‘Towns ERQUY SB 02 96 72 30 12 CLÉDER 02 98 69 43 01 ÉTABLES4SUR4MER 02 96 70 65 41 has it all.