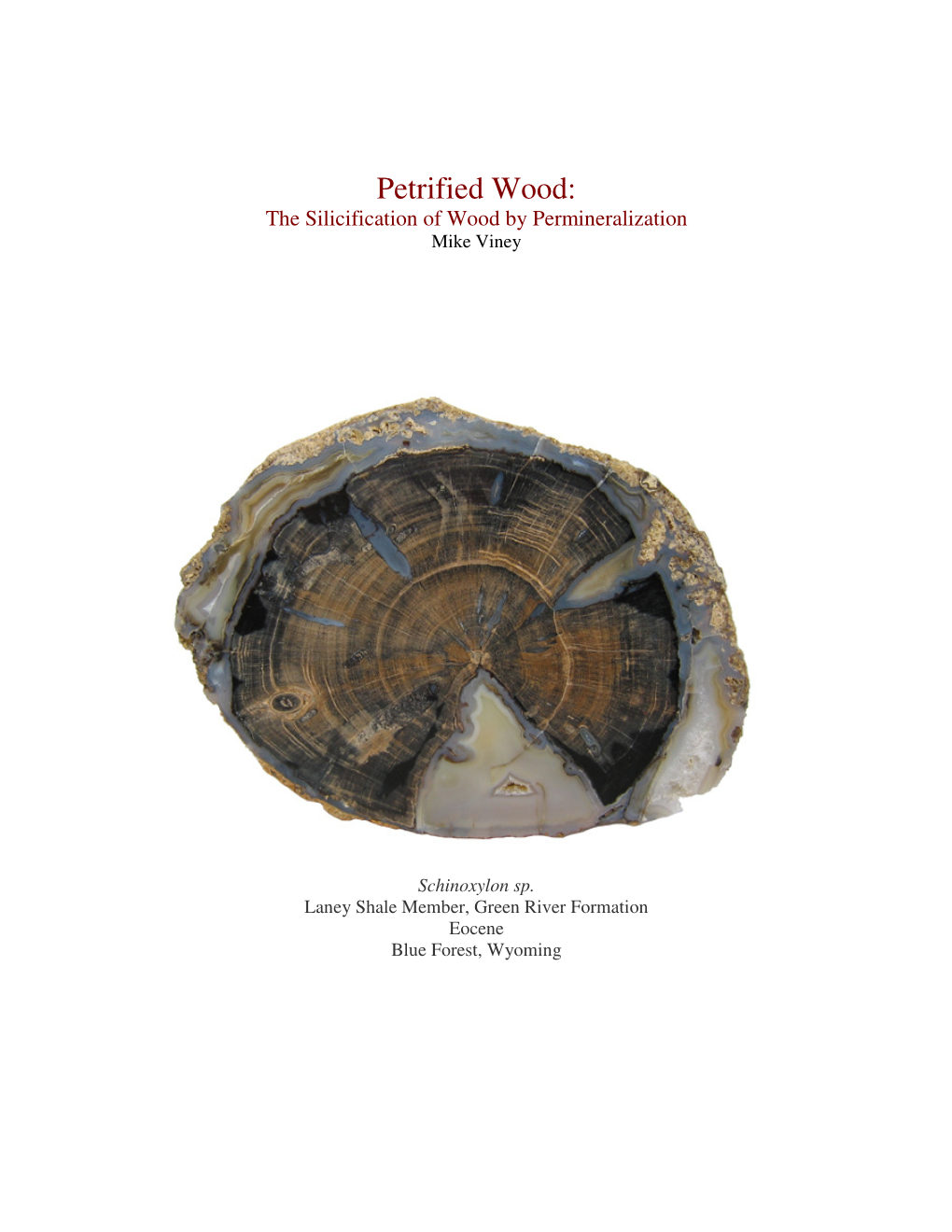

Petrified Wood : the Silicification Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Organisation of Palaeobotany IOP NEWSLETTER

INTERNATIONAL UNION OF BIOLOGIC A L S C IENC ES S ECTION FOR P A L A EOBOTANY International Organisation of Palaeobotany IOP NEWSLETTER 110 August 2016 CONTENTS FROM THE SECRETARY/TREASURER IPC XIV/IOPC X 2016 IOPC 2020 IOP MEMBERSHIP IOP EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ELECTIONS IOP WEBMASTER POSITION WHAT HAPPENED TO THE OUPH COLLECTIONS? THE PALAEOBOTANY OF ITALY UPCOMING MEETINGS CALL FOR NEWS and NOTES The views expressed in the newsletter are those of its correspondents, and do not necessarily reflect the policy of IOP. Please send us your contributions for the next edition of our newsletter (June 2016) by M ay 30th, 2016. President: Johanna Eder-Kovar (G ermany) Vice Presidents: Bob Spicer (Great Britain), Harufumi Nishida (Japan), M ihai Popa (Romania) M embers at Large: Jun W ang (China), Hans Kerp (Germany), Alexej Herman (Russia) Secretary/Treasurer/Newsletter editor: M ike Dunn (USA) Conference/Congress Chair: Francisco de Assis Ribeiro dos Santos IOP Logo: The evolution of plant architecture (© by A. R. Hemsley) I OP 110 2 August 2016 FROM THE In addition, please send any issues that you think need to be addressed at the Business SECRETARY/TREASURER meeting. I will add those to the Agenda. Dear IOP Members, Respectfully, Mike I am happy to report, that IOP seems to be on track and ready for a new Executive Council to take over. The elections are IPC XIV/IOPC X 2016 progressing nicely and I will report the results in the September/October Newsletter. The one area that is still problematic is the webmaster position. We really to talk amongst ourselves, and find someone who is willing and able to do the job. -

Ischigualasto Formation. the Second Is a Sile- Diversity Or Abundance, but This Result Was Based on Only 19 of Saurid, Ignotosaurus Fragilis (Fig

This article was downloaded by: [University of Chicago Library] On: 10 October 2013, At: 10:52 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujvp20 Vertebrate succession in the Ischigualasto Formation Ricardo N. Martínez a , Cecilia Apaldetti a b , Oscar A. Alcober a , Carina E. Colombi a b , Paul C. Sereno c , Eliana Fernandez a b , Paula Santi Malnis a b , Gustavo A. Correa a b & Diego Abelin a a Instituto y Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de San Juan , España 400 (norte), San Juan , Argentina , CP5400 b Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas , Buenos Aires , Argentina c Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, and Committee on Evolutionary Biology , University of Chicago , 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago , Illinois , 60637 , U.S.A. Published online: 08 Oct 2013. To cite this article: Ricardo N. Martínez , Cecilia Apaldetti , Oscar A. Alcober , Carina E. Colombi , Paul C. Sereno , Eliana Fernandez , Paula Santi Malnis , Gustavo A. Correa & Diego Abelin (2012) Vertebrate succession in the Ischigualasto Formation, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32:sup1, 10-30, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2013.818546 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2013.818546 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology EDUCATOR's GUIDE

Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Dear Educator: This guide is recommended for educators of grades K-4 and is designed to help you prepare students for their Alf Museum visit, as well as to provide resources to enhance your classroom curriculum. This packet includes background information about the Alf Museum and the science of paleontology, a summary of our museum guidelines and what to expect, a pre-visit checklist, a series of content standard-aligned activities/exercises for classroom use before and/or after your visit, and a list of relevant terms and additional resources. Please complete and return the enclosed evaluation form to help us improve this guide to better serve your needs. Thank you! Paleontology: The Study of Ancient Life Paleontology is the study of ancient life. The history of past life on Earth is interpreted by scientists through the examination of fossils, the preserved remains of organisms which lived in the geologic past (more than 10,000 years ago). There are two main types of fossils: body fossils, the preserved remains of actual organisms (e.g. shells/hard parts, teeth, bones, leaves, etc.) and trace fossils, the preserved evidence of activity by organisms (e.g. footprints, burrows, fossil dung). Chances for fossil preservation are enhanced by (1) the presence of hard parts (since soft parts generally rot or are eaten, preventing preservation) and (2) rapid burial (preventing disturbance by bio- logical or physical actions). Many body fossils are skeletal remains (e.g. bones, teeth, shells, exoskel- etons). Most form when an animal or plant dies and then is buried by sediment (e.g. -

La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas

La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas Edited by John M. Harris Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series 42 September 15, 2015 Cover Illustration: Pit 91 in 1915 An asphaltic bone mass in Pit 91 was discovered and exposed by the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art in the summer of 1915. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History resumed excavation at this site in 1969. Retrieval of the “microfossils” from the asphaltic matrix has yielded a wealth of insect, mollusk, and plant remains, more than doubling the number of species recovered by earlier excavations. Today, the current excavation site is 900 square feet in extent, yielding fossils that range in age from about 15,000 to about 42,000 radiocarbon years. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Archives, RLB 347. LA BREA AND BEYOND: THE PALEONTOLOGY OF ASPHALT-PRESERVED BIOTAS Edited By John M. Harris NO. 42 SCIENCE SERIES NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Luis M. Chiappe, Vice President for Research and Collections John M. Harris, Committee Chairman Joel W. Martin Gregory Pauly Christine Thacker Xiaoming Wang K. Victoria Brown, Managing Editor Go Online to www.nhm.org/scholarlypublications for open access to volumes of Science Series and Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Los Angeles, California 90007 ISSN 1-891276-27-1 Published on September 15, 2015 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas PREFACE Rancho La Brea was a Mexican land grant Basin during the Late Pleistocene—sagebrush located to the west of El Pueblo de Nuestra scrub dotted with groves of oak and juniper with Sen˜ora la Reina de los A´ ngeles del Rı´ode riparian woodland along the major stream courses Porciu´ncula, now better known as downtown and with chaparral vegetation on the surrounding Los Angeles. -

Unit- V Paleobotany

18MBO21C-U5 PAPER – IV PLANT DIVERSITY - II (PTERIDOPHYTES, GYMNOSPERMS AND PALEOBOTANY) Unit- V Paleobotany Dr. A. SANKARAVADIVOO, Assistant Professor, Department of Botany Government Arts College(Autonomous), Coimbatore-641018. Mobile:9443704273 GEOLOGICAL TIME SCALE Fossilization The method by which fossils are formed is termed as fossilization. Optimal conditions for fossilization are that an organism is buried very soon after its death and in the absence of bacterial or fungal decay, that mineral-rich waters and sediments surround the site, and the immediate environment is cool and hypoxic. The root of the word fossil derives from the Latin verb ‘to dig’ (fodere). A fossil is the mineralized partial or complete form of an organism, or of an organism’s activity, that has been preserved as a cast, impression or mold. A fossil gives tangible, physical evidence of ancient life and has provided the basis of the theory of evolution in the absence of preserved soft tissues. A Pectinatites Mould of a bivalve ammonite, shell Preserved insect trapped in amber Fossil recod . The totality of fossils - their placement in fossiliferous, rock formations, sedimentary layers (strata) . Fossil record - important functions of the science of paleontology - vary in size . A fossil normally preserves only a portion of the deceased organism, bones and teeth of vertebrates, the chitinous or calcareous exoskeletons of invertebrates. The oldest human fossil, where human refers to Homo erectus, Homo ergaster, and Homo georgicus, was a set of five skulls found in Dmanisi in Georgia between 1999 and 2005. These date back to approximately 1.8 million years ago. The oldest fossil remains depict five different species of microbe, preserved in a 3.5-billion-year-old rock in Australia. -

Retallack 2021 Coal Balls

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 564 (2021) 110185 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Modern analogs reveal the origin of Carboniferous coal balls Gregory Retallack * Department of Earth Science, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1272, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Coal balls are calcareous peats with cellular permineralization invaluable for understanding the anatomy of Coal ball Pennsylvanian and Permian fossil plants. Two distinct kinds of coal balls are here recognized in both Holocene Histosol and Pennsylvanian calcareous Histosols. Respirogenic calcite coal balls have arrays of calcite δ18O and δ13C like Carbon isotopes those of desert soil calcic horizons reflecting isotopic composition of CO2 gas from an aerobic microbiome. Permineralization Methanogenic calcite coal balls in contrast have invariant δ18O for a range of δ13C, and formed with anaerobic microbiomes in soil solutions with bicarbonate formed by methane oxidation and sugar fermentation. Respiro genic coal balls are described from Holocene peats in Eight Mile Creek South Australia, and noted from Carboniferous coals near Penistone, Yorkshire. Methanogenic coal balls are described from Carboniferous coals at Berryville (Illinois) and Steubenville (Ohio), Paleocene lignites of Sutton (Alaska), Eocene lignites of Axel Heiberg Island (Nunavut), Pleistocene peats of Konya (Turkey), and Holocene peats of Gramigne di Bando (Italy). Soils and paleosols with coal balls are neither common nor extinct, but were formed by two distinct soil microbiomes. 1. Introduction and Royer, 2019). Although best known from Euramerican coal mea sures of Pennsylvanian age (Greb et al., 1999; Raymond et al., 2012, Coal balls were best defined by Seward (1895, p. -

XRF Workshop Book

Workshop Materials (1 of 2) Table of Contents Workshop Materials (book 1 of 2) Page Agenda 1 Welcome Presentation (Steve Kaczmarek) 3 Lectures Introduction to the Chemistry of Rocks and Minerals (Peter Voice) 7 Geology of Michigan (Bill Harrison) 22 XRF Theory (Steve Kaczmarek) 44 Student Research Posters Silurian A-1 Carbonate (Matt Hemenway) 56 Silurian Burnt Bluff Group (Mohamed Al Musawi) 58 Classroom Activities Powder Problem 60 Fossil Free For All 69 Bridge to Nowhere 76 Get to Know Your Pet Rock 90 Forensic XRF 92 Alien Agua 96 Appendices (book 2 of 2) Appendix A: MGRRE Factsheet 105 Appendix B: Michigan Natural Resources Statistics 107 Appendix C: CoreKids Outreach Program 126 Appendix D: Graphing & Statistical Analysis Activity 138 Appendix E: K-12 Science Performance Expectations 144 Appendix F: Workshop Evaluation Form 179 Workshop Facilitators Bridging the Gap between Geology & Chemistry Sponsored by the Western Michigan University, the Michigan Geological Repository for Research and Education, and the U.S. National Science Foundation This workshop is for educators interested in learning more about the chemistry of geologic materials. Wednesday, August 9, 2017 (8 am - 5 pm) Tentative Agenda 8:00-8:20: Welcome (Steve Kaczmarek) Agenda, Safety, & Introductions 8:20-8:50: Introduction to Geological Materials (Peter Voice) An introduction to rocks, minerals, and their elemental chemistry 8:50-9:00: Questions/Discussion 9:00-9:30: Introduction to MI Basin Geology (Bill Harrison) An introduction to the common rock types and economic -

Mineralogy of Non-Silicified Fossil Wood

Article Mineralogy of Non-Silicified Fossil Wood George E. Mustoe Geology Department, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA 98225, USA; [email protected]; Tel: +1-360-650-3582 Received: 21 December 2017; Accepted: 27 February 2018; Published: 3 March 2018 Abstract: The best-known and most-studied petrified wood specimens are those that are mineralized with polymorphs of silica: opal-A, opal-C, chalcedony, and quartz. Less familiar are fossil woods preserved with non-silica minerals. This report reviews discoveries of woods mineralized with calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate, various iron and copper minerals, manganese oxide, fluorite, barite, natrolite, and smectite clay. Regardless of composition, the processes of mineralization involve the same factors: availability of dissolved elements, pH, Eh, and burial temperature. Permeability of the wood and anatomical features also plays important roles in determining mineralization. When precipitation occurs in several episodes, fossil wood may have complex mineralogy. Keywords: fossil wood; mineralogy; paleobotany; permineralization 1. Introduction Non-silica minerals that cause wood petrifaction include calcite, apatite, iron pyrites, siderite, hematite, manganese oxide, various copper minerals, fluorite, barite, natrolite, and the chromium- rich smectite clay mineral, volkonskoite. This report provides a broad overview of woods fossilized with these minerals, describing specimens from world-wide locations comprising a diverse variety of mineral assemblages. Data from previously-undescribed fossil woods are also presented. The result is a paper that has a somewhat unconventional format, being a combination of literature review and original research. In an attempt for clarity, the information is organized based on mineral composition, rather than in the format of a hypothesis-driven research report. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88715-1 - An Introduction to Plant Fossils Christopher J. Cleal & Barry A. Thomas Index More information Index Abscission 33, 76, 81, 82, 119, Antarctica 25, 26, 93, 117, 150, 153, Baiera 169 150, 191 209, 212 Balme, Basil 24 Acer 195, 198, 216 Antheridia 56, 64, 88 Bamboos 197 Acitheca 49, 119 Antholithus 31 Banks, Harlan P. 28 Acorus 194 Araliaceae 191 Baragwanathia 28, 43, 72, 74 Acrostichum 129, 130 Araliosoides 187 Bark 67 Actinocalyx 190 Araucaria 157, 159, 160, 164, 181 Barsostrobus 76 Adpressions 3, 4, 9, 12, 38 Araucariaceae 163, 212, 214 Barthel, Manfred 21 Agathis 157 Araucarites 163 Bean, William 29 Agavaceae 192 Arber, Agnes 19, 65 Beania 30 Agave 193 Arber, E. A. Newell 18, 19, 30 ReconstructionofBeania-tree169,172 Aglaophyton 64 Arcellites 133 Bear Island 94, 95 Agriculture 220 Archaeanthus 187, 189 Beck, Charles 69 Alethopteris 46, 144, 145 Archaeocalamitaceae 97, 205 Belgium 19, 22, 39, 68, 112, 129 Algae 55 Archaeocalamites 9799, 100, 105 Belize 125 Alismataceae 194 Archaeopteridales 69 Bennettitales 33, 157, 170, 171, Allicospermum 165 Archaeopteris 39, 40, 68, 69, 71, 153 172174, 182, 211214 Allochthonous assemblages 3, 11 Archaeosperma 137, 139 Bennie, James 24 Alnus 24, 179, 216 Archegonia 56, 135, 137 Bentall, R. 24 Aloe 192 Arctic-Alpine flora 219 Bertrand, Paul 18 Alternating generations 1, 5557, 85 Arcto-Tertiary flora 117, 215, 216 Bertrandia 114 Amerosinian Flora 96, 97, 205, Argentina 3, 77, 130, 164 Betulaceae 179, 195, 215 206, 208 Ariadnaesporites 132 Bevhalstia 188 Amber, preservation in 7, 42, 194 Arnold, Chester 28, 29, 67 Binney, Edward 21 Anabathra 81 Arthropitys 97, 101 Biomes 51 Andrews, Henry N. -

Uranium -Vanadium Deposits of the Thompsons Area Grand County, Utah

UTAH GEOLOGICAL AND MINERALOGICAL SURVEY AFFILIATED WITH THE COLLEGE OF MINES AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES UNIVERSITY OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH Uranium -Vanadium Deposits Of the Thompsons Area Grand County, Utah WITH EMPHASIS ON THE Origin of Carnotite Ores BY WM. LEE STOKES Published with the aid of a grant from the University of Utah Research Fund Bulletin 46 December, 1952 Price $1.00 UTAH GEOLOGICAL AND MINERALOGICAL SURVEY AFFILIATED WITH THE COLLEGE OF MINES AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES UNIVERSITY OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH UraniUIIl oW Vanadiurn Deposits Of the Thompsons Area Grand County, Utah WITH EMPHASIS ON THE Origin of Carnotite Ores BY WM. LEE STOKES Published with the aid of a grant from the University of Utah Research Fund Bulletin 46 December, 1952 Price $1.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword .......................................................................................................... 5 Abstract 7 Introduction .................................................................................................... 7 Stratigraphy ................................................. _.................................................. 8 Pre-Summerville rocks . _____ .... __ ........ __ .. __ .. _.... _.... __ ._ ... __ ... __ ..... _............. _._._.. 9 Summerville formation .. ______ ._ .. __ ._ ...... ____ ......... _............... _.. __ .... __ ........... _.. _. 10 Morrison formation .. _. __ . ___ .. ______ ..... _. _____ ._ .. __ ...... ______ ... _... _____ ._ ... _._ .. __ . _____ .. ____ 11 Origin of Morrison formation .... _.... ___ .... __ . __ .. _........ __ .. __ ........ __ .. __ .... ____ .... 13 Fluvial features of Morrison formation .. __ .. __ .... _____ . __ ... ___ ...... _.. _... _... _.. 15 Paleontology of Morrison formation __ . ____ ._ .. __ .... __ ..... _. ____ . ___ . __ ._ ...... __ .. 18 Cedar Mountain formation ......... ___ .... __ ._. ___ . _____ .... __ . _____ .. _.. ____ . __ ....... _... ____ . 19 Dakota sandstone and Mancos shale ._. -

How Fossils Form

I* How Fossils Form 4.5.a Getting the Idea You may not know it, but all around us is evidence Key Words | of Earth's past. Rocks, fossils, tree rings, glacial fossil snow, and other geologic features can give us clues about Earth's paleontologist history. Fossils are the preserved remains of plants and animals body fossil petrifaction or the traces left by plants and animals, such as footprints. A trace fossil paleontologist is a scientist who studies fossils to learn about plants and animals that lived in former geologic periods. Types of Fossils Fossils can provide information about the size and shape of extinct organisms. Fossils can even tell us about their growth patterns and diseases. By studying fossils, paleontologists can make scientific determinations about the climate or weather of the past. Different types of fossils give us clues to Earth's past environment and the organisms that lived on Earth. In general, scientists refer to two main types of fossils: body fossils and trace fossils. Body fossils are the remains of an organism. They can be just part of an organism, or they may be the entire organism. Body fossils can include actual pieces of an organism, such as bones, shells, teeth, or seeds. These parts are sometimes preserved through processes such as petrifaction. Petrifaction occurs when the organic material of an organism is replaced with minerals and "turned into stone." A piece of petrified wood looks like the original wood, but all of the wood molecules have been replaced with minerals. Lesson 43: How Fossils Form The process of petrifaction explains how some fossils were formed.