Framing the Debate by KR Moore the Latin Vulgate Bible's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T C K a P R (E F C Bc): C P R

ELECTRUM * Vol. 23 (2016): 25–49 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.16.002.5821 www.ejournals.eu/electrum T C K A P R (E F C BC): C P R S1 Christian Körner Universität Bern For Andreas Mehl, with deep gratitude Abstract: At the end of the eighth century, Cyprus came under Assyrian control. For the follow- ing four centuries, the Cypriot monarchs were confronted with the power of the Near Eastern empires. This essay focuses on the relations between the Cypriot kings and the Near Eastern Great Kings from the eighth to the fourth century BC. To understand these relations, two theoretical concepts are applied: the centre-periphery model and the concept of suzerainty. From the central perspective of the Assyrian and Persian empires, Cyprus was situated on the western periphery. Therefore, the local governing traditions were respected by the Assyrian and Persian masters, as long as the petty kings fulfi lled their duties by paying tributes and providing military support when requested to do so. The personal relationship between the Cypriot kings and their masters can best be described as one of suzerainty, where the rulers submitted to a superior ruler, but still retained some autonomy. This relationship was far from being stable, which could lead to manifold mis- understandings between centre and periphery. In this essay, the ways in which suzerainty worked are discussed using several examples of the relations between Cypriot kings and their masters. Key words: Assyria, Persia, Cyprus, Cypriot kings. At the end of the fourth century BC, all the Cypriot kingdoms vanished during the wars of Alexander’s successors Ptolemy and Antigonus, who struggled for control of the is- land. -

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147 Chapter 8 Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? Dis/unity, Gender and Orientalism in the Fourth Century Shaun Tougher Introduction In the narrative of relations between East and West in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, the tensions between the eastern and western imperial courts at the end of the century loom large. The decision of Theodosius I to “split” the empire between his young sons Arcadius and Honorius (the teenage Arcadius in the east and the ten-year-old Honorius in the west) ushered in a period of intense hostility and competition between the courts, famously fo- cused on the figure of Stilicho.1 Stilicho, half-Vandal general and son-in-law of Theodosius I (Stilicho was married to Serena, Theodosius’ niece and adopted daughter), had been left as guardian of Honorius, but claimed guardianship of Arcadius too and concomitant authority over the east. In the political manoeu- vrings which followed the death of Theodosius I in 395, Stilicho was branded a public enemy by the eastern court. In the war of words between east and west a key figure was the (probably Alexandrian) poet Claudian, who acted as a ‘pro- pagandist’ (through panegyric and invective) for the western court, or rather Stilicho. Famously, Claudian wrote invectives on leading officials at the eastern court, namely Rufinus the praetorian prefect and Eutropius, the grand cham- berlain (praepositus sacri cubiculi), who was a eunuch. It is Claudian’s two at- tacks on Eutropius that are the inspiration and central focus of this paper which will examine the significance of the figure of the eunuch for the topic of the end of unity between east and west in the Roman Empire. -

1 the Best of the Macedonians

The Best of the Macedonians: Alexander as Achilles in Curtius’ History of Alexander Traditionally, Quintus Curtius Rufus’ History of Alexander, the main Latin source for the reign of Alexander the Great, has been studied primarily from a historical perspective, with the majority of scholarship being devoted to the historian’s date and sources (e.g., Dosson 1887, Tarn 1948, Atkinson 1980, Hammond 1983). More recently, however, scholars have become increasingly aware that Curtius’ work, like all ancient historiography, contains a marked literary dimension as well, and, as a result, have begun to study the work from a more literary perspective (e.g., Currie 1990, Baynham 1998, Spencer 2002). Following in this growing tradition of literary scholarship on Curtius, I seek in this paper to shed light on one particular aspect of Curtius’ complex, but underappreciated, literary design: his portrayal of Alexander as a second Achilles. While based on historical fact, Curtius’ depiction of Alexander as Achilles serves, I argue, a particular literary purpose, namely, to highlight the dark side of Alexander’s character—his ira and his vis—and, thereby, to reinforce the central moralizing theme of the work as a whole. In the first section, I present the case for Curtius’ depiction of Alexander as Achilles. To begin with, I consider the passages where Curtius makes the Alexander-Achilles connection explicit: (i.) Alexander at the siege of Gaza, where Curtius compares Alexander’ act of dragging Betis’ body around Gaza to Achilles’ act of dragging Hector’s body around Troy (Curt. 4.6.29); (ii.) Alexander’s marriage to Roxane, where Curtius depicts Alexander as justifying his marriage to a barbarian wife by reference to Achilles’ quasi-marriage to Briseis (Curt. -

The Impossible Dream W. W. Tarn's Alexander in Retrospect*

F LASHBACKS Karanos 2, 2019 77-95 The Impossible Dream W. W. Tarn’s Alexander in Retrospect* by A. Brian Bosworth The University of Western Australia First published in 1948, Tarn’s Alexander the Great was soon out of print. In 1956 the first volume was republished in paperback under the auspices of Beacon Press in Boston, but the more substantial second volume remained inaccessible and was a collector’s item for decades. I myself had a standing order with Blackwell’s from 1967, but it was at the end of a long list and eventually after much persuasion I received personal permission to make my own photocopy of the work. At long last in 1979 both volumes were reissued in matching format, exact and uncorrected reprints of the original, and they are now available in Australia**. It must be said at once that it is twenty years too late. Virtually every major statement made by Tarn has been critically examined over the last two and a half decades and in almost every case rejected. His work on Alexander is now a historical curiosity, valuable as a document illustrating his own emotional and intellectual make-up but practically worthless as a serious history of the Macedonian conqueror. As will be seen, Tarn’s attitudes and methods are interesting in their own right, but they are not interesting enough to justify the outrageous and exorbitant price that is demanded of the Australian market. Hard pressed school librarians would make a far better investment by acquiring a range of more recent publications. -

Alexander's Successors

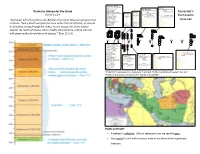

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander -

Alexander the Not So Great William Baran Bill Ba

______________________________________________________________________________ Alexander the Not So Great William Baran Bill Baran, from Crystal Lake, Illinois, wrote "Alexander the Not So Great" during his senior year for Dr. Lee Patterson's Alexander the Great course in Fall 2015. He is currently a senior, majoring in history, and expects to graduate in May 2016. ______________________________________________________________________________ “It is perhaps Ptolemy who first coined the title ‘Great’ to describe Alexander, an epithet that has stayed with him to this day.”1 Whether or not this is true, somewhere along the way Alexander inherited the title “Great,” but is it one that he deserves? Alexander is responsible for expanding Macedonian territory significantly and it is something that he could not have accomplished alone. Since the backing of the army was crucial, why did some of Alexander’s generals not live past the life of Alexander? Although some of the generals and other army personnel inevitably died while in battle, others did not receive such a glorified death. Under Alexander’s rule numerous people in his army were murdered or died under suspicious circumstances. The death witnessed while Alexander ruled did not end there, because the army as a whole often suffered due to poor decision making on Alexander’s part. Whether direct or indirect Alexander ordered or caused the deaths of many because of anger, suspicion, or by poor choices. Alexander does not deserve the title “Great,” because of the deliberate killing under his command of both individuals and his army. Before embarking on the journey of tearing down Alexander’s title, it is important to understand the transition from Philip II to Alexander. -

The Contest for Macedon

The Contest for Macedon: A Study on the Conflict Between Cassander and Polyperchon (319 – 308 B.C.). Evan Pitt B.A. (Hons. I). Grad. Dip. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Tasmania October 2016 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does this thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 ii Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed alone, and I am forever grateful to my supervisor, mentor and friend, Dr Graeme Miles, who has unfailingly encouraged and supported me over the many years. I am also thankful to all members of staff at the University of Tasmania; especially to the members of the Classics Department, Dr Jonathan Wallis for putting up with my constant stream of questions with kindness and good grace and Dr Jayne Knight for her encouragement and support during the final stages of my candidature. The concept of this thesis was from my honours project in 2011. Dr Lara O’Sullivan from the University of Western Australia identified the potential for further academic investigation in this area; I sincerely thank her for the helpful comments and hope this work goes some way to fulfil the potential she saw. -

The Bare Necessities: Ascetic Indian Sages in Philostratus' 'Life of Apollonius'

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 The Bare Necessities: Ascetic Indian Sages in Philostratus' 'Life of Apollonius' Samuel McVane College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation McVane, Samuel, "The Bare Necessities: Ascetic Indian Sages in Philostratus' 'Life of Apollonius'" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 362. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/362 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction One might not think that much direct contact occurred between the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome and ancient India. The civilizations lay thousands of miles apart, a vast distance for men who traveled by foot or horse. But in fact, we have much evidence, both material and literary, for rather extensive contact – economic, military, and cultural – between the ancient East and West. One of the most interesting interactions, in my opinion, was the intellectual exchange between the West and ancient Indian philosophers, sages, and religious thinkers. Fortunately, we have a great body of extant ancient Western literature – primarily in Greek – that provide numerous accounts and descriptions, historic, pseudo- historic, and fictional, of Indian wise men and their interactions with the West. This body of literature particularly focuses on portrayals of Indian ascetics who lived a very frugal lifestyle, scorning most material needs, in the pursuit of knowledge. -

The Demise of Alexander Death of Alexander

4/10/2012 21. The Successors of Alexander’s Empire Diadochoi Seleucus I (Nikator) Ptolemy I (Soter) Perdiccas Antigonus Monophthalmus Partition at Triparadeisos (320) Battle of Ipsus (301) First Syrian War 275 BCE (5 all together) Ptolemaic Kingdom Seleucia (before and after Ipsus) Antigonid Kingdom Kingdom of Pergamon Parthia The Demise of Alexander Death of Alexander "... the motive in almost every heart was grief and a sort of helpless bewilderment at the thought of losing their king. Lying speechless as the men filed by, he yet struggled to raise his head, and in his eyes there was a look of recognition for each individual as he passed... Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, VII. 27. 1 4/10/2012 The Death of Alexander 11 June 323 BCE Over next week Alexander’s health rapidly declined • At one moment, he was so desperate that he gave his ring to Perdiccas and when asked to whom the ring should be given, some believe he replied: – “tôi Kraterôi” (To Krateros) or – “tôi kratistôi” (to the strongest). Difficulty in choosing a Successor Macedonian army command leant itself to selecting a leader—but … Many potential top candidates were dead or incapable: • Clitus-killed in drunken rage • Parmenion-executed • Hephaestion-died of fever (malaria) • Philip III (younger brother)-mentally deficient • Alexander IV (son with Roxanne)-too young Perdiccas took overall command and came to agreement with other generals – would act as regent for Philip III and Alex IV 2 4/10/2012 Alexander’s Generals Seleucus I Ptolemy page under helped -

Court Intrigue and the Death of Callisthenes Lara O’Sullivan

Court Intrigue and the Death of Callisthenes Lara O’Sullivan MPLICATED IN A PLOT by the Royal Pages (the basilikoi paides) against Alexander’s life in Bactria in 327 B.C.E., the historian I Callisthenes was condemned as a traitor and died—either tortured and hanged, or imprisoned and carted about with the army until disease brought about his death.1 His demise marks something of a nadir in Alexander’s reign; indeed, centuries after the fact, Curtius could claim that no one’s execution incited greater resentment of Alexander among the Greeks (nullius caedes maiorem apud Graecos Alexandro excitavit invidiam).2 The reason for that resentment is not difficult to discover. Despite the avowals of the Alexander-apologists that the Pages had implicated Cal- listhenes, his supposed involvement in the plot was unsupported by evidence. Arrian concedes as much, observing that most traditions had no indication of Callisthenes’ guilt, while Plutarch cites a letter purportedly written by the king himself in the im- mediate aftermath of the conspiracy, in which the Pages were said to have confessed under torture that the conspiracy was en- tirely their own, and that nobody else was cognizant of the plot.3 The underlying cause of Callisthenes’ downfall is, instead, 1 For Callisthenes’ fate Arr. 4.14.3 cites divergent accounts by Ptolemy FGrHist 138 F17 (put to death; so too Curt. 8.8.21) and Aristobulus FGrHist 139 F 33 (died while imprisoned). Aristobulus clearly based his account on Chares (FGrHist 125 F 15 = Plut. Alex. 55.9). 2 Curt. 8.8.22. -

L. Prandi, Fortuna E Realtà Dell'opera Di Clitarco

Histos () - REVIEW −DISCUSSION IN SEARCH OF CLEITARCHUS Luisa Prandi, Fortuna e realtà dell’ opera di Clitarco . ( Historia Einzel- schriften ) Pp. Steiner, Stuttgart . There is an unwritten law that the volume of scholarship on a subject is in inverse proportion to the evidence available. That is particularly true of the early Hellenistic historian, Cleitarchus, son of Deinon. In Jacoby’s definitive compendium thirty six fragments are accepted as authentic, comprising eight pages of text. On the whole these ‘fragments’ are singularly unin- formative. Few give any extended digest of Cleitarchus’ narrative, and there are only five lines of verbatim quotation. All that has survived of his work, then, is a handful of weak attestations, supplemented by a few vague and bil- ious criticisms of his style and veracity made by later authors, usually with a taste for Atticism and antipathetic to Cleitarchus. Yet Cleitarchus bulks very large in the historiography of Alexander’s reign, not for what is directly at- tested but for his supposed contribution to the extant source tradition. It is generally agreed that there is a strand of evidence common to the accounts of Diodorus, Curtius Rufus, Justin’s Epitome of Trogus and the Metz Epit- ome. The extent and pervasiveness of this tradition has been the subject of long and occasionally heated debate, but there is a general agreement (or has been since at least the time of Eduard Schwartz) that a nucleus does ex- ist, common to a string of extant, derivative historians, distorted in various ways according to the vagaries of the transcriber but deriving ultimately from an early historian independent of (and frequently in conflict with) the more ‘respectable’ accounts of Ptolemy and Aristobulus, which form the ba- sis of Arrian’s narrative. -

“Just Rage”: Causes of the Rise in Violence in the Eastern Campaigns of Alexander the Great

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “Just Rage”: Causes of the Rise in Violence in the Eastern Campaigns of Alexander the Great _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by Jenna Rice MAY 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “JUST RAGE”: CAUSES OF THE RISE IN VIOLENCE IN THE EASTERN CAMPAIGNS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT presented by Jenna Rice, a candidate for the degree of master of history, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Ian Worthington Professor Lawrence Okamura Professor LeeAnn Whites Professor Michael Barnes τῷ πατρί, ὅς ἐμοί τ'ἐπίστευε καὶ ἐπεκέλευε ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Professors Worthington, Okamura, Whites, and Barnes, for the time they spent reading and considering my thesis during such a busy part of the semester. I received a number of thoughtful questions and suggestions of new methodologies which will prompt further research of my topic in the future. I am especially grateful to my advisor, Professor Worthington, for reading through and assessing many drafts of many chapters and for his willingness to discuss and debate the topic at length. I know that the advice I received throughout the editing process will serve me well in future research endeavors. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1.