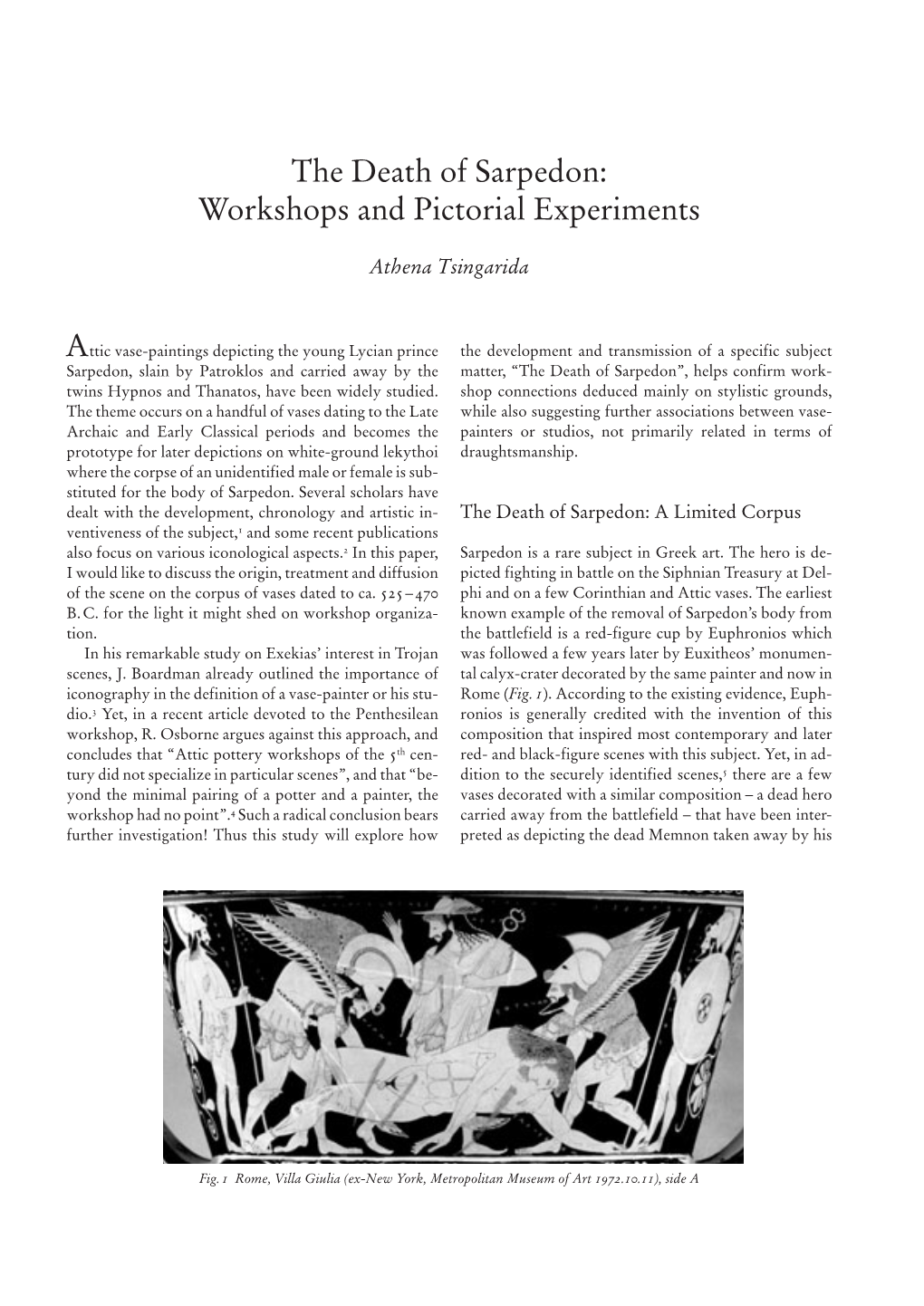

The Death of Sarpedon: Workshops and Pictorial Experiments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dottorato in Scienze Storiche, Archeologiche E Storico-Artistiche

DOTTORATO IN SCIENZE STORICHE, ARCHEOLOGICHE E STORICO-ARTISTICHE Coordinatore prof. Francesco Caglioti XXX ciclo Dottorando: Luigi Oscurato Tutor: prof. Alessandro Naso Tesi di dottorato: Il repertorio formale del bucchero etrusco nella Campania settentrionale (VII – V secolo a.C.) 2018 Il repertorio formale del bucchero etrusco nella Campania settentrionale (VII – V secolo a.C.) Sommario Introduzione ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Storia degli studi sul bucchero rinvenuto in Campania ...................................................................... 8 1. I siti e i contesti ............................................................................................................................ 16 1.1 Capua .................................................................................................................................... 18 1.2 Calatia ................................................................................................................................... 28 1.3 Cales ...................................................................................................................................... 31 1.4 Cuma ..................................................................................................................................... 38 1.5 Il kolpos kymaios ................................................................................................................... 49 2. Catalogo -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

Kourimos Parthenos

KOURIMOS PARTHENOS The fragments of an oinochoe ' illustrated here preserve for us the earliest known representation in any medium of the dress and the masks worn by actors in Attic tragedy.2 The style of the vase suggests a date in the neighborhood of 470: 3 a time, that is, when both Aischylos and Sophokles 4 were active in the theatre. Thus, even though our fragments may not shed much new light on the " dark history of the IInv. No. P 11810. Three fragments, mended from five. Height; a, 0.073 m.; b, 0.046 m.; c, 0.065 m. From a round-bodied oinochoe, Beazley Shape III; fairly thin fabric, excellent glaze; relief contour except for the mask; sketch lines on the boy's body. The use of added color is described below, p. 269. For the lower border, a running spiral, with small loops between the spirals. Inside, dull black to brown glaze wash. The fragments were found just outside the Agora Excava- tions, near the bottom of a modern sewer trench along the south side of the Theseion Square, some 200 m. to the south of the temple, at a depth of about 3 m. below the street level. 2 For the fifth century, certainly, relevant comparative material has been limited to three pieces: the relief from the Peiraeus, now in the National Museum, Athens (N. M. 1500; Svoronos, Athener Nationalmuseum, pl. 82), which shows three actors, two of them carrying masks, approaching a reclining Dionysos; the Pronomos vase in Naples (Furtwangler-Reichhold, pls. 143-145), with its elaborate preparations for a satyr-play; and the pelike in Boston, by the Phiale painter (Att. -

Catullus, Archilochus and the 'Motto'. Two Poems of Catullus Have Long Been Compared with Fragments of Ar- Chilochus

I TWO CATULLIAN QUESTIONS L Catullus, Archilochus and the 'motto'. Two poems of Catullus have long been compared with fragments of Ar- chilochus. First, Catullus 40 and Archilochus 172 West (fully discussed by Hendrickson "CP" 20, 1925, 155); qwenan te mala mew, miselle Ravide, agit praccípítem in rrcos iambos ? quid dcus rtbi nonbene ad.vocatus ve cordcm parat excímre rimn? an uî penenias ín oravulgi? quidvis? qunlubet esse natus oPns? eris, quando quidcm mcos cttnores cwn longavoluisti amare poena. n&rep Auróppa, noîov Érppóoco tó6e tíg oùg rccr,p{epe epwctg fig cò rpìv ;1pfipqoOa; vOv òè 6l rol.ùq úocoîot gcwérrt fflog. This is known to be the beginning of a poem, since Hephaestion, who quotes l-2, only adduces the beginnings of poems; 2I0 ríg &pa òaíprov (quis d.eus) raì téoo 1oX,oúpevoE may well come from the same context. Moreover, as Hendrickson remarks, Lucian's (Pseudol. 1) paraphrase of the context of 223, which he says was addressed to one of toò6 repureteîg é,oopévoog (cf. praecípítem) rfi 1ol.fr t6v iópporv crúto0 who had re- viled the poet, seems to indicate that it went with 172; ín that case Lucian's 6 rcróòatpov &v0prone=míselle, and aiticq (qtoOvtc rai ùro0é- oeqtoî6 iúpporq will help to explain Catullus' application of iantbi to hen- decasyllables (though it does not need much explanation; cf. 54.6 and fr. 3). If Catullus had Archilochus in mind, he diverged from him in the last two lines, which envisage a situaúon quite different from that between Archilo- chus and Lycambes; the poem of Archilochus seems to have continued at considerable length and included the fable of the fox and the eagle (172- 181). -

THE MAENAD in EARLY GREEK ART* R[ SHEILA MCNALLY

./ // THE MAENAD IN EARLY GREEK ART* r[ SHEILA MCNALLY HE EXAMINATIOOFN WORKSof art can provide information about a culture which significantly changes what we would know from written SOurces alone. Examination of the role of maenads in early Greek art shows a striking development, namely the waxing and waning of hostility between themselves and their companions, the satyrs. This development is, I think, symptomatic both of strains developing in the Greeks' experience and of a growing complexity in their awareness of themselves and their universe. It reflects tensions between male and female characteristics in human nature, not necessarily tensions between men and women specifically. We tend to think of satyrs and maenads as images of happy freedom. They first appear, dancing and carousing, in the painting of sixth century Greece, and wend their way with carefree sensuality through Western art down to the present day. There are, however, some startling early breaks in this pattern, eruptions of hostility such as that painted by the Kleophrades Painter around 500 B.C. (fig. 9L His maenad wards off the advances of a satyr with cool, even cruel effectiveness. This action sets her apart, not only from happier ren- ditions of the same subj ect, but from renditions of other female figures in contemporary art. Contrary to what we might expect, no other female in Greek art defends her chastity so fiercely as the maenad. No other male figure is caught at such a disadvantage as the satyr - although he has his victories too. Scenes of men and women in daily life, whether boldly erotic or quietly ceremonious, are invariably good-humored. -

From Boston to Rome: Reflections on Returning Antiquities David Gill* and Christopher Chippindale**

International Journal of Cultural Property (2006) 13:311–331. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2006 International Cultural Property Society DOI: 10.1017/S0940739106060206 From Boston to Rome: Reflections on Returning Antiquities David Gill* and Christopher Chippindale** Abstract: The return of 13 classical antiquities from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) to Italy provides a glimpse into a major museum’s acquisition patterns from 1971 to 1999. Evidence emerging during the trial of Marion True and Robert E. Hecht Jr. in Rome is allowing the Italian authorities to identify antiquities that have been removed from their archaeological contexts by illicit digging. Key dealers and galleries are identified, and with them other objects that have followed the same route. The fabrication of old collections to hide the recent surfacing of antiquities is also explored. In October 2006 the MFA agreed to return to Italy a series of 13 antiquities (Ap- pendix). These included Attic, Apulian, and Lucanian pottery as well as a Roman portrait of Sabina and a Roman relief fragment.1 This return is forming a pattern as other museums in North America are invited to deaccession antiquities that are claimed to have been illegally removed from Italy. The evidence that the pieces were acquired in a less than transparent way is beginning to emerge. For example, a Polaroid photograph of the portrait of Sabina (Appendix no. 1) was seized in the raid on the warehousing facility of Giacomo Medici in the Geneva Freeport.2 Polaroids of two Apulian pots, an amphora (no. 9) and a loutrophoros (no. 11), were also seized.3 As other photographic and documentary evidence emerges dur- ing the ongoing legal case against Marion True and Robert E. -

Attic Black Figure from Samothrace

ATTIC BLACK FIGURE FROM SAMOTHRACE (PLATES 51-56) 1 RAGMENTS of two large black-figure column-kraters,potted and painted about j1t the middle of the sixth century, have been recovered during recent excavations at Samothrace.' Most of these fragments come from an earth fill used for the terrace east of the Stoa.2 Non-joining fragments found in the area of the Arsinoeion in 1939 and in 1949 belong to one of these vessels.3 A few fragments of each krater show traces of burning, for either the clay is gray throughout or the glaze has cracked because of intense heat. The surface of many fragments is scratched and pitted in places, both inside and outside; the glaze and the accessory colors, especially the white, have sometimes flaked. and the foot of a man to right, then a woman A. Column krater with decoration continuing to right facing a man. Next is a man or youtlh around the vase. in a mantle facing a sphinx similar to one on a 1. 65.1057A, 65.1061, 72.5, 72.6, 72.7. nuptial lebes in Houston by the Painter of P1. 51 Louvre F 6 (P1. 53, a).4 Of our sphinx, its forelegs, its haunches articulated by three hori- P.H. 0.285, Diam. of foot 0.203, Th. at ground zontal lines with accessory red between them, line 0.090 m. and part of its tail are preserved. Between the Twenty-six joining pieces from the lower forelegs and haunches are splashes of black glaze portion of the figure zone and the foot with representing an imitation inscription. -

Colloquia Pontica Volume 10

COLLOQUIA PONTICA VOLUME 10 ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 COLLOQUIA PONTICA Series on the Archaeology and Ancient History of the Black Sea Area Monograph Supplement of Ancient West & East Series Editor GOCHA R. TSETSKHLADZE (Australia) Editorial Board A. Avram (Romania/France), Sir John Boardman (UK), O. Doonan (USA), J.F. Hargrave (UK), J. Hind (UK), M. Kazanski (France), A.V. Podossinov (Russia) Advisory Board B. d’Agostino (Italy), P. Alexandrescu (Romania), S. Atasoy (Turkey), J.G. de Boer (The Netherlands), J. Bouzek (Czech Rep.), S. Burstein (USA), J. Carter (USA), A. Domínguez (Spain), C. Doumas (Greece), A. Fol (Bulgaria), J. Fossey (Canada), I. Gagoshidze (Georgia), M. Kerschner (Austria/Germany), M. Lazarov (Bulgaria), †P. Lévêque (France), J.-P. Morel (France), A. Rathje (Denmark), A. Sagona (Australia), S. Saprykin (Russia), T. Scholl (Poland), M.A. Tiverios (Greece), A. Wasowicz (Poland) ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 BY CATHERINE MORGAN EDITED BY G.R. TSETSKHLADZE BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 All correspondence for the Colloquia Pontica series should be addressed to: Aquisitions Editor/Classical Studies or Gocha R. Tsetskhladze Brill Academic Publishers Centre for Classics and Archaeology Plantijnstraat 2 The University of Melbourne P.O. Box 9000 Victoria 3010 2300 PA Leiden Australia The Netherlands Tel: +61 3 83445565 Fax: +31 (0)71 5317532 Fax: +61 3 83444161 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Illustration on the cover: Athenian vessel, end of the 5th-beg. of the 4th cent. -

Volgei Nescia: on the Paradox of Praising Women's Invisibility*

Matthew Roller Volgei nescia: On the Paradox of Praising Women’s Invisibility* A funerary plaque of travertine marble, originally from a tomb on the Via Nomentana outside of Rome and dating to the middle of the first century BCE, commemorates the butcher Lucius Aurelius Hermia, freedman of Lucius, and his wife Aurelia Philematio, likewise a freedman of Lucius. The rectangular plaque is divided into three panels of roughly equal width. The center panel bears a relief sculpture depicting a man and woman who stand and face one another; the woman raises the man’s right hand to her mouth and kisses it. The leftmost panel, adjacent to the male figure, is inscribed with a metrical text of two elegiac couplets. It represents the husband Aurelius’ words about his wife, who has predeceased him and is commemorated here. The rightmost panel, adjacent to the female figure, is likewise inscribed with a metrical text of three and one half elegiac couplets. It represents the wife Aurelia’s words: she speaks of her life and virtues in the past tense, as though from beyond the grave.1 The figures depicted in relief presumably represent the married individuals who are named and speak in the inscribed texts; the woman’s hand-kissing gesture seems to confirm this, as it represents a visual pun on the cognomen Philematio/Philematium, “little kiss.”2 This relief, now in the British Museum, is well known and has received extensive scholarly discussion.3 Here, I wish to focus on a single phrase in the text Aurelia is represented as speaking. -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Athenian Potters and Painters Volume III Belongs to the Publishers Oxbow Books and It Is Their Copyright

This pdf of your paper in Athenian Potters and Painters Volume III belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but be- yond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (August 2017), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). An offprint from Athenian Pot ters and Painters Volume III edited by John H. Oakley Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-663-9 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-664-6 © Oxbow Books 2014 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by OXBOW BOOKS 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083 © Oxbow Books and the individual authors 2014 Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-663-9 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-664-6 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2010290514 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing. Printed in the United Kingdom by Short Run Press, Exeter For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact: UNITED KINGDOM Oxbow Books Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) -

Greek Dramatic Monuments from the Athenian Agora and Pnyx

GREEK DRAMATIC MONUMENTS FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA AND PNYX (PLATES 65-68) T HE excavations of the Athenian Agora and of the Pnyx have produced objects dating from the early fifth century B.C. to the fifth century after Christ which can be termed dramatic monuments because they represent actors, chorusmen, and masks of tragedy, satyr play and comedy. The purpose of the present article is to interpret the earlier part of this series from the point of view of the history of Greek drama and to compare the pieces with other monuments, particularly those which can be satisfactorily dated.' The importance of this Agora material lies in two facts: first, the vast majority of it is Athenian; second, much of it is dated by the context in which it was found. Classical tragedy and satyr play, Hellenistic tragedy and satyr play, Old, Middle and New Comedy will be treated separately. The transition from Classical to Hellenistic in tragedy or comedy is of particular interest, and the lower limit has been set in the second century B.C. by which time the transition has been completed. The monuments are listed in a catalogue at the end. TRAGEDY AND SATYR PLAY CLASSICAL: A 1-A5 HELLENISTIC: A6-A12 One of the earliest, if not the earliest, representations of Greek tragedy is found on the fragmentary Attic oinochoe (A 1; P1. 65) dated about 470 and painted by an artist closely related to Hermonax. Little can be added to Miss Talcott's interpre- tation. The order of the fragments is A, B, C as given in Figure 1 of Miss T'alcott's article. -

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Malibu 2 (Bareiss) (25) CVA 2

CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM UNITED STATES OF AMERICA • FASCICULE 25 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Fascicule 2 This page intentionally left blank UNION ACADÉMIQUE INTERNATIONALE CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM • MALIBU Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined closed shape, and lids from neck-amphorae ANDREW J. CLARK THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM FASCICULE 2 . [U.S.A. FASCICULE 25] 1990 \\\ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (Revised for fasc. 2) Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America.] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. (Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23) Fasc. 1- by Andrew J. Clark. At head of title: Union académique internationale. Includes index. Contents: fasc. 1. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes.—fasc. 2. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined open shape, and lids from neck-amphorae 1. Vases, Greek—Catalogs. 2. Bareiss, Molly—Art collections—Catalogs. 3. Bareiss, Walter—Art collections—Catalogs. 4. Vases—Private collections— California—Malibu—Catalogs. 5. Vases—California— Malibu—Catalogs. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. I. Clark, Andrew J., 1949- . IL J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Series: Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23, etc. NK4640.C6U5 fasc. 23, etc. 738.3'82'o938o74 s 88-12781 [NK4624.B37] [738.3'82093807479493] ISBN 0-89236-134-4 (fasc.