Notorious but Invisible: How Romani Media Portrayals Invalidate Romani Identity and Existance in Mainstream Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great “Gypsy” Round-Up in Spain

PROJECT EDUCATION OF ROMA | HISTORY ROMA CHILDREN COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE IN EUROPE THE GREAT “GYPSY” 3.3 ROUND-UP IN SPAIN The Great Antonio Gómez Alfaro “Gypsy” Round-up in Spain A Preventive Security Measure l A Favourable Juncture l The Strategy l Funding the Round-up l The Prisoners’ Destination l Review of the Round-up l Problems with Freed “Gypsies” l The Reasons for the Pardon l An Unexpected Delay The Age of Enlightened Absolutism provided the authorities with increasing opportunities to apply their measures on all the citizens in their range of power. In Spain, this resulted in the most painful episode in the history of the country’s “Gypsy” community: the general round-up carried out during the reign of Ferdinand VI, on July 30, 1749. The operation, which was as thorough as it was indiscriminate, led to the internment of ten to twelve thousand people, men and women, young and old, “simply because they were Gypsies.” The co-ordination of the different public authorities involved, the co-operation of the Church, which remained passive in the face of such injustice, the excesses committed by all those who made the operation possible, and the collaboration of the prisoners’ fellow citizens and neighbours made “Black Wednesday”, as the round-up is also called, an unchallenged event in the long history of European anti-“Gypsyism”. Oviedo A S T U R I A S CANTABRIA BASQUE NUMBER OF “GYPSY” FAMILIES DOMICILED COUNTRY Following a list by the Council of Castile, probably of 1749 N A V A R R E Ill. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Promoting the Social Inclusion of Roma

EU NETWORK OF INDEPENDENT EXPERTS ON SOCIAL INCLUSION PROMOTING THE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF ROMA HUGH FRAZER AND ERIC MARLIER (NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH, CEPS/INSTEAD) DECEMBER 2011 SYNTHESIS REPORT On behalf of the Disclaimer: This report reflects the views of its authors European Commission and these are not necessarily those of either the DG Employment, Social Affairs European Commission or the Member States. and Inclusion The original language of the report is English. EU NETWORK OF INDEPENDENT EXPERTS ON SOCIAL INCLUSION PROMOTING THE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF ROMA HUGH FRAZER AND ERIC MARLIER (NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH, CEPS/INSTEAD) DECEMBER 2011 SYNTHESIS REPORT Overview based on the national reports prepared by the EU Network of Independent Experts on Social Inclusion Disclaimer: This report reflects the views of its authors and these are not necessarily those of either the European Commission or the Member States. The original language of the report is English. On behalf of the European Commission DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion SYNTHESIS REPORT Contents Preface 3 Summary, conclusions and suggestions 4 A. Summary 4 A.1 Overview of the situation of the Roma in the European Union (EU) 4 A.2 Assessment of existing policy and governance frameworks and identification of key policy priorities to be addressed in national Roma integration strategies 6 B. Conclusions and suggestions 12 1. Overview of the Situation of the Roma in the EU 16 1.1 Roma population across the EU 16 1.2 Geographical variations within countries 20 1.3 Poverty and social exclusion of Roma 22 1.3.1 Income poverty and deprivation 23 1.3.2 Educational disadvantage 24 1.3.3 Employment disadvantage 27 1.3.4 Poor health 30 1.3.5 Inadequate housing and environment 32 1.3.6 Limited access to sport, recreation and culture 34 1.4 Widespread discrimination and racism 35 1.5 Gender discrimination 38 1.6 Extensive data gaps 39 2. -

The Political Status of the Romani Language in Europe. Mercator Working Papers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 303 FL 027 781 AUTHOR Bakker, Peter; Rooker, Marcia TITLE The Political Status of the Romani Language in Europe. Mercator Working Papers. SPONS AGENCY European Union, Brussels (Belgium). REPORT NO WP-3 ISSN ISSN-1133-3928 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 37p.; Produced by CIEMEN (Escarre International Centre for Ethnic Minorities and Nations), Barcelona, Spain. Contains small print. AVAILABLE FROM CIEMEN, Rocafort 242, bis, 08020 Barcelona,(Catalunya), Spain. Tel: 34-93-444-38-00; Fax: 34-93-444-38-09; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.ciemen.org/mercator. For full text: http://www.ciemen.org/mercator/ pdf/wp3-def-ang.PDF. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil Rights; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Language Usage; Language of Instruction; *Minority Groups;,Public Policy; *Regional Dialects; Sociolinguistics IDENTIFIERS European Union; *Gypsies; Roma ABSTRACT This paper examines the political status of Romani. the language of the Gypsies/Roma, in the European Union (EU). Even though some groups do not call themselves "Roma," all Romani speaking groups use the name "Romanes" for their language and "Romani/Romano/Romane" for everything related to their group. All groups use the same language, and all languages can be subdivided into dialects. Three aspects make Romani dialects more diverse than other EU dialects: absence of centuries long influence from a standard language or prestige dialect; influence from a variety of local languages; and a great number of communities of Romani speakers (with speakers not all in contact with each other). -

Traveller's History of Ireland

Traveller's History Of Ireland If searched for the ebook Traveller's History of Ireland in pdf form, then you have come on to the loyal site. We presented utter variant of this book in doc, DjVu, PDF, txt, ePub forms. You may read Traveller's History of Ireland online either load. Withal, on our site you can read guides and another artistic eBooks online, or downloading them. We like to draw your consideration that our website not store the book itself, but we give reference to the website where you can downloading or reading online. If you have necessity to downloading Traveller's History of Ireland pdf, then you have come on to the correct site. We have Traveller's History of Ireland doc, PDF, ePub, txt, DjVu formats. We will be glad if you go back more. the traveller's histories: ireland traveller's - The Traveller's Histories: Ireland Traveller'S History Of: Amazon.es: Peter Neville: Libros en idiomas extranjeros ireland ( traveller's history of ireland) by - - Ireland (Traveller's History of Ireland): The Traveller's History series is designed for travellers who want more historical background on the country they are target : expect more pay less - free shipping on orders of $25+ & free returns on everything. view details . shop all categories expand. clothing, shoes & jewelry opens a flyout; baby & kids opens a traveller's history of ireland - 9781905214693 - - Traveller's History of Ireland - Peter R. Neville - Travel & holiday guides - 9781905214693 documents and ebooks related to a traveller s - Documents and ebooks related to A Traveller s History of Ireland Traveller s History Series at generalebookdownload.org. -

Online Event Evidence and Research for Roma Children— RECI

Online event Evidence and Research for Roma Children— RECI Reports: Decade of Collaboration Date: December 8, 2020 Time: 14:00-16:00 GMT/15:00-17:00 CET _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Agenda Welcome Keynote address RECI series – Achievements and challenges Presentation and reflections from RECI partners Q&A Panel discussion 1: What do we need to do to promote equal access to health and education for Roma children? What is the role of research in policy making, practice and advocacy? Q&A Panel discussion 2: Roma children’s inclusion today. (What has been achieved in the past 10 years? Where are countries now? What are the main problems? What is the impact of COVID1-19 on Roma children and their families? What data are available and what data are missing? Q&A Conclusions and takeaway messages _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Speakers with affiliation • Zuzana Havirova Balazova - Director of Roma Advocacy and Research Center, Slovakia • Ivelina Borisova - Regional Advisor, UNICEF • Redjepali Chupi, Interim Co-Director, Roma Education Fund • Dan Pavel Doghi - Senior Adviser on Roma and Sinti Issues, Chief of the CPRSI at OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE ODIHR) • Roland Ferkovics - independent advocacy expert • Jana Hainsworth - Secretary General, Eurochild • Jana Huttova - Consultant, OSF • Arthur Ivatts - Consultant, OSF • Anita Jones - Program -

A Travellers' Sense of Place in the City

A Travellers’ Sense of Place in the City Anthony Leroyd Howarth Wolfson College University of Cambridge August 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology. A Travellers’ Sense of Place in the City Anthony Howarth Abstract It is widely assumed in both popular and scholarly imaginaries that Travellers, due to their ‘nomadic mind-set’ and non-sedentary uses of land, do not have a sense of place. This thesis presents an ethnographic account of an extra-legal camp in Southeast London, to argue that its Traveller inhabitants do have a sense of place, which is founded in the camp’s environment and experientially significant sites throughout the city. The main suggestion is that the camp, its inhabitants, and their activities, along with significant parts of the city, are co-constitutionally involved in making a Travellers’ sense of place. However, this is not self- contained or produced by them alone, as their place-making activities are embroiled in the political, economic and legal environment of the city. This includes the threat and implementation of eviction by a local council, the re-development of the camp’s environs, and other manifestations of the spatial-temporalities of late-liberal urban regeneration. The thesis makes this argument through focusing on the ways that place is made, sensed, and lived by the camp’s Traveller inhabitants. It builds on practice-based approaches to place, centred on the notion of dwelling, but also critically departs from previous uses of this notion by demonstrating that ‘dwelling’ can occur in an intensely politicised and insalubrious environment. -

CPRSI Newsletter

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights CPRSI Newsletter August 1996 Vol.2 No. 4 A group numerically inferior to the rest of the population of the state, in a non-dominant position, whose members being nationals of the State - possess ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics differing from those of the rest of the population and show, if only implicitly, a sense of solidarity, directed towards presenting their culture, traditions, religion or language. INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial............................................................................................................................... The Travelling Communities - History, Culture and Educational Opportunities, by Arthur Ivatts ..................................................................................................................................... Roma As National Minority, by Noboru Miyawaki ............................................................... The Marginalisation of Gypsies (Exerts), by Helen O'Nions LL.M.................................... Czech Photoproject.............................................................................................................. Book reviews: Struggling for Ethnic Identity............................................................................................... The Great Gypsy Round-Up................................................................................................. Reports submitted to the CPRSI............................................................................................. -

GSN Edition 12-10-20

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2013 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 81, Number 99 10 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 giving season Trout released into county lake By Kevin Bottrell least one more release in January or February, The trout season is open until April 15. always bring a buddy as well as rope and a [email protected] and may do a third if the budget allows. Spalsbury said temperatures in the lake can throwable life preserver, which can also be Angel Tree The Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks For most, fishing in the lake will require a change very quickly, and he expects there to used to sit up off the ice. and Tourism has released what could be the license and a trout stamp, which are sold at be a freeze once the wind dies down. Ice fish- Spalsbury said the state will continue to first of many new fish into the lake at Smoky Walmart. For people aged 16 to 74, a valid ing can be dangerous, but Spalsbury offered manage the water levels in Smoky Gardens and Toys Gardens, just in time for ice fishing season. license is required with a trout stamp. Spals- some guidelines to stay safe. using water from the state fishing lake. When Fisheries Biologist Dave Spalsbury said bury said people will have to get a 2013 stamp “You need five to six inches of deep, clear the weather warms up again next year, he about 400 rainbow trout were released into if they want to fish in the month of December ice,” he said. -

The Power of Definition. Stigmatisation, Minoritisation1 and Ethnicity Illustrated by the History of Gypsies in the Netherlands*

THE POWER OF DEFINITION. STIGMATISATION, MINORITISATION1 AND ETHNICITY ILLUSTRATED BY THE HISTORY OF GYPSIES IN THE NETHERLANDS* LEO LUCASSEN Introduction Various groups of immigrants have settled in the Netherlands over the past centuries. This process generally took place without big problems, apart from the almost ritual phase of a not very flattering stereotype, with the result that none of the original immigrants still exist as a group. There are no German, Huguenot or southern Dutch minorities left. The history of Jews and gypsies was quite different. Although they have lived in the Netherlands for centuries, they have always stayed minorities. The question is why? Was integration or assimilation blocked because they were totally ‘different’, or was the attitude of the host society to blame? In this article I will restrict myself to the gypsies and try to shed some light on this hitherto unsolved problem by means of an historical analysis. I use the term ‘stigmatisation’ (following Van Arkel 1985) because there was (and is) a lot of confusion about who should be considered ‘gypsies’. Contrary to studies that start from the assumption that it is mainly a matter of self-definition, 1 consider that stigmatisation can stimulate group formation – and along with it ethnic consciousness – to a great extent. Two aspects of ‘stigmatisation’ are distinguished for analytical purposes: a) the dissemina- tion of negative ideas about a specific group (stigma) by an authoritative body; and b) the attachment of this stigma on specific groups (labelling) A separate analysis of labelling is of paramount importance in situations where it is unclear who is considered as a group-member; this was the case not only with gypsies, but also with other groups such as homosexuals and political opponents. -

Austro-Hungarian Empire

PROJECT EDUCATION OF ROMA | HISTORY ROMA CHILDREN COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE IN EUROPE AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN 3.1 EMPIRE Austro-Hungarian compiled by the editors Empire A New Method: Assimilation | The Four Decrees of Maria Theresia | Little Success | Failed Attempts in Spain and Germany Already at an early stage, people had tried to stop the Roma from living their way of life and culture. On a larger scale, however, policies of assimilation to the majority population were only pushed ahead by rulers in the Age of Enlightened Absolutism. Empress Maria Theresia and her son Joseph II in particular pursued programs which aimed at the Roma’s settlement and assimilation. Instead of physical violence a new form of cruelty was used in order to transform the uncontrollable and, to the state, unproductive “Gypsies” into settled, profitable subjects: the Roma were given land, they were no longer allowed to speak Romani and marry among each other, they were registered, and finally their children were taken away. However, these measures succeeded only in Western Hungary, today’s Austrian Burgenland and adjacent areas. In the other territories of the Empire, as well as in Spain and Germany, where the pressure for assimilation was likewise increased, the rulers’ policy of assimilation failed. COMITATUS MOSON INTRODUCTION (WIESELBURG) The Age of Enlightened Absolutism was characterised by essential changes in the sovereigns’ policies toward the “Gypsies”. In the face of the complete failure of all attempts to banish them COMITATUS permanently from their dominion, the SOPRON sovereigns of the Enlightenment were (ÖDENBURG) searching for new methods and ways to solve the “Gypsy problem” from the second half of the 18th century onwards. -

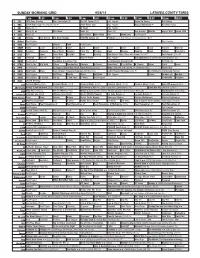

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna.