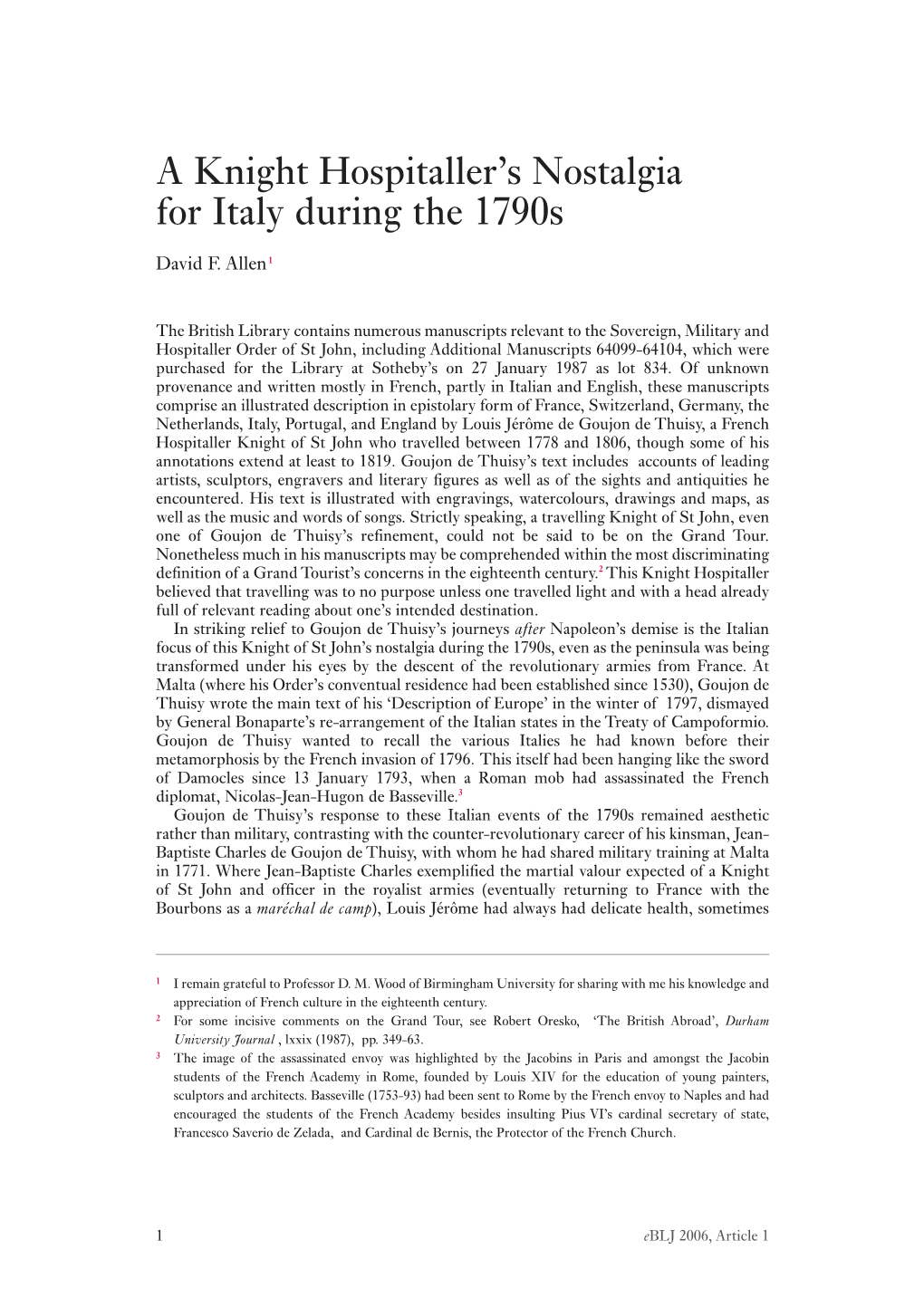

A Knight Hospitaller's Nostalgia for Italy During The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 1, 2021

Our Lady of the Angels & Our Lady of the Valley Parishes Rev. Scott A. Gratton, Administrator: Rev. John R. Carroll, Visiting Priest: (Deployed) (617)699-5425 Email: [email protected] Mr. Josh Perry, Diocesan Administrator: Elizabeth Stuart, Parish Secretary: (802)448-3515 (513)238-4854 – cell Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Our Lady of the Angels St. Anthony Parish Office Information: St. Elizabeth 221 Church Street 43 Hebard Hill Road 169 S. Main Street P O Box 63 P O Box 428 Rochester, VT 05767 Bethel, VT 05032 Randolph VT 05060 Office:(802)728-5251 Email: [email protected] Eighteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time Confessions Sat.: 3:00– 3:45 PM St. E., Rochester Sun.: 8:00—8:45 AM OLA, Randolph & After the 11:00 AM Mass, St. A., Bethel Or by Appointment Adoration of the Bl. Sacrament Sat.: 3:00—4:00 PM, St. E. Mon.: 7:00—8:00 AM, St. A. Tues.: 5:15—6:15 PM, St. A. Wed.: 4:00-5:00 PM, St. E 5:00 –6:00 PM, OLA Thurs: 8:30—9:30 AM, OLA Fri: 8:30-9:30 AM, OLA Weekend Masses 2:00-3:00 PM, St. A. Sat.: 4:00 PM St. E., Rochester Sun.: 9:00 AM OLA, Randolph 11:00 AM St. A., Bethel www.ourladyvt.org 18th Sunday of Ordinary Time 1 August 2021 Remember your loved ones in the Holy Mass GARDENING ASSISTANCE NEEDED: – they will be forever grateful to you! CALLING ALL GARDENERS, or anyone that can help pull weeds, rake beds or otherwise be of help – on Saturday, July 31st – come and work THIS WEEKEND: at St. -

&>Ff) Jottfck^ ^Di^Kcs<

fiEOHSTERED AS A NEWSPAPER. &>ff) jotTfCK^ ^di^KCs<. dltaf xoittiffi foiflj Spiritualism m <&xmt §ntaitt( THE SPIRITUALIST is regularly on Sale at the following places:—LONDON : xr, Ave Maria-lane, St. Paul’s Churchyard, E.C. PARIS: Kiosque 246, Boule- vard des Capucines, and 7, Rue de Lille. LEIPZIG: 2, Lindenstrasse. FLORENCE: Signor G. Parisi, Via della Maltonaia. ROME: Signor Bocca, Libraio, Via del Corso. NAPLES: British Reading Rooms, 267, Riviera di Chiaja, opposite the Villa Nazionale. LIEGE: 37, Rue Florimont. BUDA- PESTH : Josefstaadt Erzherzog, 23, Alexander Gasse. MELBOURNE : 96, Russell-street. SHANGHAI : Messrs. Kelly & Co. NEW YORK: Harvard Rooms, Forty-second-street & Sixth-avenue. BOSTON, U.S.: “Banner of Light” Office, 9, Montgomery-place. CHICAGO : “ Religio-Philosophical Journal” Office. MEMPHIS, U.S.: 7, Monroe-street. SAN FRANCISCO: 319, Kearney-street. PHILADELPHIA: 918, Spring Garden-street. WASHINGTON": No. xoio, Seventh-street. No. 316. (VOL. XIII.—No. 11.) LONDON: FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 1878. Published Weekly; Price Twopence. (Contents. BRITISH NATIONAL ASSOCIATION THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OF SPIRITUALISTS, GREAT BRITAIN, Suggestions for the Future ... ...121 The Cure of Diseases near Sacred Tombs:—Extract 38, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, BLOOMSBURY W.O. 11, Chandos Street, Cavendish Square, London, W from a Letter Written by a Physician at Rome to his Entrance in Woburn Street. PRESIDENT—MR. SERJEANT COX. Sister, a Carmelite Nun, at Cavaillon, dated May 1, 1783—Extract from a Letter from an English Gentle- This Society was established in February. 1875, for the pro- man at Rome, dated June 11, 1783—Extract from a CALENDAR FOR SEPTEMBER. motion of psychological science in all its branches. -

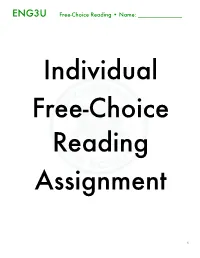

ENG3U Free Choice Reading

ENG3U Free-Choice Reading • Name: ______________ Individual Free-Choice Reading Assignment 1 Free Choice Important Literary Authors by Period & Culture Beginning to 1st 2nd-15th 16th Century 17th Century 18th Century 19th Century 20th Century Century A.D. Century (1500s) (1600s) (1700s) (1800s) (1900s) Indian Manu, Valmiki Chandidas, The Ghazal Khan Kushal Mirza Ghalib Mahatma Subcontinental Kabir Gandhi, Premchand Chinese I Ching, Tao Yangming Hong Shen Yuan Mei, Mao Zedong, Confucius Yuanming, Xie Wang, Wu Cao Xueqin Lin Yutang Lingyun Cheng’en Japanese Manyoshu Zeami Kojiro Kanze Matsuo Basho Hakuin Ekaku Natsume Mishima Motokiyo Soseki Yukio Middle Eastern Gilgamesh, Book Talmud, Jami, Thousand and Evliya Çelebi Jacob Talmon, of the Dead, The Rumi One Nights David Shar, Bible Amos Oz Greek Homer, Aesop, Anna Dionysios Constantine Sophocles, Comnena, Solomos Cavafy, Euripides Ptolemy, Giorgos Galen, Seferis, Porphyry Odysseas Elytis Latin Virgil, Ovid, St. Anselm of Desiderius Johannes Carolus Pope Pius X, Cicero Aosta, St. Erasmus, Kepler, Linnaeus XI, XII Thomas Thomas Baruch Aquinas, St. Moore, John Spinoza Augustine Calvin Germanic Neibelungenli Martin Luther Johann Immanuel Johann Rainer Maria ed, Van Grimmelshau Kant, Wolfgang von Rilke, Bertolt Eschenbach, sen Friedrich von Goethe, Brecht, Albert Von Schiller Brothers Schweitzer Strassburg Grimm, Karl Marx, Henrik Ibsen French Le Chanson Robert René Voltaire, Jean- Honoré de Marcel Proust, de Roland, Garnier, Descartes, Jacques Balzac Victor Jean-Paul Jean Froissart, Marguerite -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Palazzo del Te: Art, Power, and Giulio Romano’s Gigantic, yet Subtle, Game in the Age of Charles V and Federico Gonzaga A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies with emphases in Art History and Political Science By Diana L. Michiulis December 2016 The thesis of Diana L. Michiulis is approved: ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. David Leitch Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to convey my deepest, sincere gratitude to my Thesis Committee Chair, Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, for all of her guidance, insights, patience, and encourage- ments. A massive "merci beaucoup" to Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux, without whom completion of my Master’s degree thesis would never have been fulfilled. It was through Dr. Bordeaux’s leadership, patience, as well as his tremendous knowledge of Renaissance art, Mannerist art, and museum art collections that I was able to achieve this ultimate goal in spite of numerous obstacles. My most heart-felt, gigantic appreciation to Dr. David Leitch, for his leadership, patience, innovative ideas, vast knowledge of political-theory, as well as political science at the intersection of aesthetic theory. Thank you also to Dr. Owen Doonan, for his amazing assistance with aesthetic theory and classical mythology. I am very grateful as well to Dr. Mario Ontiveros, for his advice, passion, and incredible knowledge of political art and art theory. And many thanks to Dr. Peri Klemm, for her counsel and spectacular help with the role of "spectacle" in art history. -

Egypt Returns to Mann

EGYPT RETURNS TO MANN ( The Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli ) by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli Photos Courtesy the MANN he palace which houses the Museo Archeologico Nazion- ale di Napoli (The Naples National Archaeological Muse- um) — known by its abbreviation MANN — was built in 1585 as a cavalry barracks. It’s located at the western edge of the neighborhood called “Quartieri Spagnoli” (Spanish Quarters), because in the Sixteenth Century the Spanish oc - T cupied and ruled Naples. In those days the building was just outside the city walls, in an area (St. Teresa) that had once been one of the many ancient Greek cemeteries of Neapolis . Between 1612 and 1615, the Viceroy Pedro Fer - nández de Castro (1560-1622) had the palace transformed into the University of Naples; he gave the job of restruc - turing and enlarging the building to the highly respected architect/engineer Giulio Cesare Fontana. Then in 1777 King Ferdinand IV (1751-1825) transferred the Univer - sity to the Jesuit convent and started to make this palace the Museo Ercolanese (of the artifacts from the early ex - Above, One of the new state-of-the-art instal - cavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum), the Collezione lations of the MANN Farnese (the Farnese painting collection), the library, the Egyptian collection. 59 Kmt School of Art and the laboratories for art restoration — although the idea of having a single museum devoted to archaeology had been that of his father, Charles III (1716- 1788). Then in 1816 Ferdinand established the Real Museo Borbonico (the Royal Bour- bon Museum). With the unification of Italy in 1860, the Museum building and all its contents became the property of the Italian government and its name was changed again to Museo Nazionale. -

STUIBER, Maria, Zwischen Rom Und Dem Erdkreis

38. STUIBER, Maria, Zwischen Rom und dem Erdkreis. Die gelehrte Korrespondenz des Kardinals Stefano Borgia (1731–1804). (Colloquia Augustana; 31). Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2012. 460 pp. Stefano Borgia was born in Velletri. His family, in spite of the name Borgia, cannot be traced back to the famous Aragonese Borjas. Stefano’s uncle Alessandro Borgia, the well-reputed and erudite archbishop and prince of Fermo, became the young man’s teacher, role model and quasi father (p. 77). Stefano studied philosophy and theology, showed great archeological interest and talent, and when he left his uncle’s palace in 1756, he was immediately received into the Respublica litteraria: the time’s scientific community, the - so to speak - supranational state of scholars: a commonwealth of learning that communicated especially through letter writing. This kind of long distance interaction has found historians’ increasing attention: network analysis of learned letters. It was not only his education that allowed Stefano Borgia to correspond easily within that international Respublica, it would soon also be his position: Stefano Borgia moved to Rome, lived at the Accademia Ecclesiastica and obtained a canon law doctorate from Sapienza University only a year later. After his 1757 Ascension homily for the Pope and the Cardinals, he moved to the waiting list for an administrative career in the Papal States (p. 85). He served as a governor for five years and as secretary to various Roman dicasteries before reaching his great platform: he was made secretary of the Propaganda Fide congregation. Now, he could write letters without even having to pay postage or taxes (p. -

Shakespeare in Italy Author(S): Agostino Lombardo Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol

Shakespeare in Italy Author(s): Agostino Lombardo Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 141, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), pp. 454-462 Published by: American Philosophical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/987221 Accessed: 01-04-2020 11:03 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Philosophical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society This content downloaded from 94.161.168.118 on Wed, 01 Apr 2020 11:03:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Shakespeare in Italy AGOSTINO LOMBARDO Dipartimento di Anglistica, Universita di Roma, "La Sapienza" it hacius, Spenns, Drayton, Shakespier ... ": in this list of confused and mangled names we find the first mention of Shakespeare in Italian writing. The author was probably that brilliant and versatile essayist, Lorenzo Magalotti, who wrote in 1667 the account of a journey to England. The account, indeed, gives such an interesting description of life in Restoration London as to make us regret the complete absence of any allusions to the Shakespearean performances Magalotti must have attended, as he did others of a more frivolous nature ("Wrestling, bull and bear baiting. -

Introduction

Introduction Karen Ascani, Paola Buzi and Daniela Picchi History can be ungenerous towards those who are involved in writing it. Such has been the destiny of Georg Zoëga, a distinguished Egyptologist, Coptologist, Archaeologist, and Numismatist, whose scientific and cultural contributions— highly valued by his contemporaries—fell almost entirely into oblivion with the end of the Enlightenment. Born in Denmark from a family of Venetian origin, Georg Zoëga had firm cultural roots both in his native country and in Italy, where he lived from 1783 until his death in 1809. Rome and the scholarly circle under the patronage of Cardinal Stefano Borgia became Zoëga’s home, where he welcomed many international scholars, ‘celebrities’, and dear friends, such as Goethe, Heyne, Dolomieu, Münter, Thorvaldsen. In 1769 Stefano Borgia,1 who was born in Velletri (Rome) in 1731 and died in Lyons in 1804, began to set up a collection, containing precious objects and curiosities from all over the world. The Museo Borgiano, on display at the Borgia Palace of Velletri, became one of the must-see destinations of the Italian Grand Tour, visited by scholars and other interested, mostly foreign, travellers, on their way from Rome to Naples. It was one of the most famous encyclopaedic museums in Italy, relevant also at European level, the only eighteenth-century residence-museum in Europe boasting Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, Pre-Latin, Roman, Arabic and Indian texts and artefacts, besides Medieval paintings and liturgical objects, maps, and the like that the Catholic missionaries would send to Borgia, as Secretary (and later Prefect) of the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

The Story of the Borgias (1913)

The Story of The Borgias John Fyvie L1BRARV OF UN ,VERSITV CALIFORNIA AN DIEGO THE STORY OF THE BORGIAS <Jt^- i//sn6Ut*4Ccn4<s flom fte&co-^-u, THE STORY OF THE BOEGIAS AUTHOR OF "TRAGEDY QUEENS OF THE GEORGIAN ERA" ETC NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS 1913 PRINTED AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS TAVI STOCK STREET CoVENT GARDEN LONDON THE story of the Borgia family has always been of interest one strangely fascinating ; but a lurid legend grew up about their lives, which culminated in the creation of the fantastic monstrosities of Victor Hugo's play and Donizetti's opera. For three centuries their name was a byword for the vilest but in our there has been infamy ; own day an extraordinary swing of the pendulum, which is hard to account for. Quite a number of para- doxical writers have proclaimed to an astonished and mystified world that Pope Alexander VI was both a wise prince and a gentle priest whose motives and actions have been maliciously mis- noble- represented ; that Cesare Borgia was a minded and enlightened statesman, who, three centuries in advance of his time, endeavoured to form a united Italy by the only means then in Lucrezia anybody's power ; and that Borgia was a paragon of all the virtues. " " It seems to have been impossible to whitewash the Borgia without a good deal of juggling with the evidence, as well as a determined attack on the veracity and trustworthiness of the contemporary b v PREFACE historians and chroniclers to whom we are indebted for our knowledge of the time. -

The Holy See

The Holy See HOLY MASS ON THE OCCASION OF THE HOLY FATHER'S 85TH BIRTHDAY HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Pauline Chapel Monday, 16 April 2012 Your Eminences, Dear Brothers in the Episcopate and in the Priesthood, Dear Brothers and Sisters, On the day of my birth and of my Baptism, 16 April, the Church’s liturgy has set three signposts which show me where the road leads and help me to find it. In the first place, it is the Memorial of St Bernadette Soubirous, the seer of Lourdes; then there is one of the most unusual Saints in the Church’s history, Benedict Joseph Labre; and then, above all, this day is immersed in the Paschal Mystery, in the Mystery of the Cross and the Resurrection. In the year of my birth this was expressed in a special way: it was Holy Saturday, the day of the silence of God, of his apparent absence, of God’s death, but also the day on which the Resurrection was proclaimed. We all know and love Bernadette Soubirous, the simple girl from the south, from the Pyrenees. Bernadette grew up in the France of the 18th-century Enlightenment in a poverty which it is hard to imagine. The prison that had been evacuated because it was too insanitary, became — after some hesitation — the family home in which she spent her childhood. There was no access to education, only some catechism in preparation for First Communion. Yet this simple girl, who retained a pure and honest heart, had a heart that saw, that was able to see the Mother of the Lord and the Lord’s beauty and goodness was reflected in her. -

![Unless by the Lawful Judgment of Their Peers [.Lat., Nisi Per Legale Judicum Parum Suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4577/unless-by-the-lawful-judgment-of-their-peers-lat-nisi-per-legale-judicum-parum-suorum-unattributed-author-magna-charta-privilege-of-barons-of-parliament-1144577.webp)

Unless by the Lawful Judgment of Their Peers [.Lat., Nisi Per Legale Judicum Parum Suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament

.Unless by the lawful judgment of their peers [.Lat., Nisi per legale judicum parum suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament Law is merely the expression of the will of the strongest for the time being, and .therefore laws have no fixity, but shift from generation to generation Henry Brooks Adams - .The laws of a state change with the changing times Aeschylus - .Where there are laws, he who has not broken them need not tremble ,It., Ove son leggi] [.Tremar non dee chi leggi non infranse (Vittorio Alfieri, Virginia (II, 1 - .Law is king of all Henry Alford, School of the Heart - (lesson 6) .Laws are the silent assessors of God William R. Alger - Written laws are like spiders' webs, and will like them only entangle and hold the .poor and weak, while the rich and powerful will easily break through them Anacharsis, to Solon when writing his laws - Law; an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the .community Saint Thomas Aquinas - .Law is a bottomless pit ,John Arbuthnot - (title of a pamphlet (about 1700 .Ancient laws remain in force long after the people have the power to change them Aristotle - At his best man is the noblest of all animals; separated from law and justice he is the .worst Aristotle - .The law is reason free from passion Aristotle - .Whereas the law is passionless, passion must ever sway the heart of man Aristotle - .Decided cases are the anchors of the law, as laws are of the state Francis Bacon - One of the Seven was wont to say: "That laws were like cobwebs; where the small ".flies were caught, and the great brake through (Francis Bacon, Apothegms (no.