In Memoriam: Roger Fisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating in Times of Conflict

cover Negotiating in Times of Conflict Gilead Sher and Anat Kurz, Editors Institute for National Security Studies The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), incorporating the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, was founded in 2006. The purpose of the Institute for National Security Studies is first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel’s national security as well as Middle East regional and international security affairs. Second, the Institute aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are – or should be – at the top of Israel’s national security agenda. INSS seeks to address Israeli decision makers and policymakers, the defense establishment, public opinion makers, the academic community in Israel and abroad, and the general public. INSS publishes research that it deems worthy of public attention, while it maintains a strict policy of non-partisanship. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute, its trustees, boards, research staff, or the organizations and individuals that support its research. Negotiating in Times of Conflict Gilead Sher and Anat Kurz, Editors משא ומתן בעת סכסוך גלעד שר וענת קורץ, עורכים Graphic design: Michal Semo-Kovetz and Yael Bieber Cover design: Tali Niv-Dolinsky Printing: Elinir Institute for National Security Studies (a public benefit company) 40 Haim Levanon Street POB 39950 Ramat Aviv Tel Aviv 6997556 Israel Tel. +972-3-640-0400 Fax. +972-3-744-7590 E-mail: [email protected] http:// www.inss.org.il © 2015 All rights reserved. -

THE COUNCIL for EXCELLENCE in GOVERNMENT Elliot Richardson Prize Event Acceptance Remarks

THE COUNCIL FOR EXCELLENCE IN GOVERNMENT Elliot Richardson Prize Event Acceptance Remarks Washington, D. C. March 8, 2004 Remarks By Sandra Day O’Connor Associate Justice, Supreme Court of the United States Building Bridges: The Rewarding Life of Public Service An old man, going a lone highway Came at the evening, cold and gray To a chasm, vast and deep and wide, Through which was flowing a sullen tide. The old man crossed in the twilight dim; The sullen stream had no fears for him; But he turned when safe on the other side And built a bridge to span the tide. “Old man,” said a fellow pilgrim near, “You are wasting strength with building here; Your journey will end with the ending day; You never again must pass this way; You have crossed the chasm, deep and wide— Why build you the bridge at the eventide?” The builder lifted his old gray head. “Good friend, in the path I have come,” he said, “There followeth after me today A youth whose feet must pass this way. This chasm that has been naught to me To that fair-haired youth may a pitfall be. He, too, must cross in the twilight dim; Good friend, I am building the bridge for him.” By Will Allen Dromgoole The Bridge Builder Council for Excellence in Government — Page 2 If I may, I would like to take a few moments this afternoon to talk about building bridges. Building bridges through public service Of all of the reasons that I am honored to receive this touching recognition today, the greatest is that it puts me in the company of some truly remarkable individuals who dedicated their lives to building bridges for the future of our country. -

Difficult Conversations

Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Dedication Preface Foreword Acknowledgements Introduction The Problem Chapter 1 - Sort Out the Three Conversations Shift to a Learning Stance - The “What Happened?” Conversation Chapter 2 - Stop Arguing About Who’s Right: Explore Each Other’s Stories Chapter 3 - Don’t Assume They Meant It: Disentangle Intent from Impact Chapter 4 - Abandon Blame: Map the Contribution System The Feelings Conversation Chapter 5 - Have Your Feelings (Or They Will Have You) The Identity Conversation Chapter 6 - Ground Your Identity: Ask Yourself What’s at Stake Create a Learning Conversation Chapter 7 - What’s Your Purpose? When to Raise It and When to Let Go Chapter 8 - Getting Started: Begin from the Third Story Chapter 9 - Learning: Listen from the Inside Out Chapter 10 - Expression: Speak for Yourself with Clarity and Power Chapter 11 - Problem-Solving: Take the Lead Chapter 12 - Putting It All Together Ten Questions People Ask About Difficult Conversations Notes on Some Relevant Organizations Praise for Difficult Conversations “A user-friendly guide to mastering the talks we dread . a keeper.” — Fast Company magazine “Emotional intelligence applied to life’s toughest moments.” — Daniel Goleman, bestselling author of Working with Emotional Intelligence “The only people who shouldn’t read Difficult Conversations are those who never work with people, anywhere.” — Peter M. Senge, bestselling author of The Fifth Discipline “How do you confront your ex-spouse who’s late picking up the kids? How do you tell a client -

Roger Fisher and William Ury with Bruce Patton, Editor

Getting to YES Negotiating an agreement without giving in Roger Fisher and William Ury With Bruce Patton, Editor Second edition by Fisher, Ury and Patton RANDOM HOUSE BUSINESS BOOKS 1 GETTING TO YES The authors of this book have been working together since 1977. Roger Fisher teaches negotiation at Harvard Law School, where he is Williston Professor of Law and Director of the Harvard Negotiation Project. Raised in Illinois, he served in World War II with the U.S. Army Air Force, in Paris with the Marshall Plan, and in Washington, D.C., with the Department of Justice. He has also practiced law in Washington and served as a consultant to the Department of Defense. He was the originator and executive editor of the award-winning series The Advocates. He consults widely with governments, corporations, and individuals through Conflict Management, Inc., and the Conflict Management Group. William Ury, consultant, writer, and lecturer on negotiation and mediation, is Director of the Negotiation Network at Harvard University and Associate Director of the Harvard Negotiation Project. He has served as a consultant and third party in disputes ranging from the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to U.S.-Soviet arms control to intracorporate conflicts to labor- management conflict at a Kentucky coal mine. Currently, he is working on ethnic conflict in the Soviet Union and on teacher-contract negotiations in a large urban setting. Educated in Switzerland, he has degrees from Yale in Linguistics and Harvard in anthropology. Bruce Patton, Deputy Director of the Harvard Negotiation Project, is the Thaddeus R. Beal Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School, where he teaches negotiation. -

Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition

PRINT Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition John R. Schermerhorn, Jr. Ohio University James G. Hunt Texas Tech University Richard N. Osborn Wayne State University ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 7TH edition Copyright 2002 © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-471-22819-2 (ebook) 0-471-42063-8 (print version) Brief Contents SECTION ONE 1 Management Challenges of High Performance SECTION FOUR 171 Organizations 81 Organizational Behavior Today 3 Illustrative Case: Creating a High Performance Power 173 Learning About Organizational Behavior 5 Organization 84 Empowerment 181 Organizations as Work Settings 7 Groups in Organizations 87 Organizational Politics 183 Organizational Behavior and Management 9 Stages of Group Development 90 Political Action and the Manager 186 Ethics and Organizational Behavior 12 Input Foundations of Group Effectiveness 92 The Nature of Communication 190 Workforce Diversity 15 Group and Intergroup Dynamics 95 Essentials of Interpersonal Communication Demographic Differences 17 Decision Making in Groups 96 192 Aptitude and Ability 18 High Performance Teams 100 Communication Barriers 195 Personality 19 Team Building 103 Organizational Communication 197 Personality Traits and Classifications 21 Improving Team Processes 105 -

WILLIAM URY, the Course That Will Finally Be

CONCILIA LLC. PRESENTS WILLIAM URY, the course that will finally be. Oct. 12Tth 2012, VICENZA, ITALY. The course is a European exclusive and seats are limited. Ury is considered one of the greatest trainers and facilitators in international training scene: a world authority in the field of negotiation. Consultant and broker for over thirty years in the business / political, and popular author of the recent bestseller "The positive NO". To download the course brochure for URY: www.concilia.it/william_ury_eng.pdf To download the registration form: www.concilia.it/reg_eng.pdf Info and registration: CONCILIA LLC. [email protected] T.: (39) 0642016845 F.: (39) 0693387583 y OBER 2012 T THE POWER OF A POSITIVE enza 12 OC no illiam Ur ic Practices and innovative strategies for effective negotiating W V Seminar with William Ury an exclusive seminar brought to you by Club Mondiale della Formazione™ fter great speakers like Brian Tracy, Robert YOUR TRAINER Cialdini, Jeffrey Gitomer and Jack ACanfield, Hi-Performance and Club Mondiale della Formazione have the pleasure to introduce the most brilliant speaker worldwide about negotiation: WILLIAM URY William Ury is the author of the just-published The Power of a Positive No: How to Say No & Still Get to Yes and co-author (with Roger Fisher) of Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, a five million-copy bestseller translated into over 20 languages. Ury is also author of the award-winning Getting Past No: Negotiating with Difficult People and Getting To Peace. WILLIAM URY CONSULTANT AND MEDIATOR IN POLITICAL AND BUSINESS ISSUES His most recent publication “The Power William Ury is co-founder of Harvard’s Program on Negotiation and currently directs the Global Negotiation Project. -

Parker House Boston, Massachusetts April 2, 1986

Parker House Boston, Massachusetts April 2, 1986 Welcome to this 40th New England Circle, another in a series of these gatherings inaugurated here in this room more than a decade ago. As it has been since that February evening in 1974, our pur- pose has remained steadfast: to provide a forum for the discussion of social, political, educational and literary topics that can lead to constructive change in our lives, our nation, and our world. The Circle's foundations were begun in the Nineteenth Cen- tury when Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Charles Dickens and the other literary lions of the day gathered regularly at the Parker House for meetings of the Saturday Club. Their traditions of a lively exchange of opinions and ideas in a hospitable and informal setting are still the founda- tions of today's Circles: a private, non-profit activity which has welcomed more than 1,500 members from every corner of the region. It is a setting which encourages easy and open exchanges between discussion leaders and every Circle guest. This evening's discussion leader is Roger Fisher, Williston Professor of Law at Harvard University. A member of the Harvard Law School faculty since 1958, Prof. Fisher is known as much for his work outside the classroom as within. As the director of the Harvard Negotiation Project, he leads a team of some of the world's most skillful negotiators and mediators. In the process, he has acquired an international reputation for finding ways to conclude non-violent agreements in situations that appeared to make violence inevitable. -

{Download PDF} Power of a Positive No, the Ebook

POWER OF A POSITIVE NO, THE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Ury | 257 pages | 19 Feb 2008 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553384260 | English | New York, United States The Power of a Positive No by William Ury: | : Books The challenge is What Is A positive No? Stage One: 1. Is your intention to protect and advance your core interests. Stage One: 2. Stage One: 3. Stage Two: 5. Taylor, but Susan cannot stay in the humanities class. Susan has a right to be included with her peers. We will have to find a way to make it work. Stage Two: 6. The next day, he signed up for a golf tour on the weekend! The woman was unhappy because her husband missed the point : She wanted him to spend more time at home with her and their children. She had delivered her No, but without the positive request that would make it clear what she wanted. Make your request respectful Your manner can make the difference between acceptance and refusal. Stage Three: 7. Keep your focus on what matters to you. Use the power of not reacting Stage Three: 8. You reiterate your limits in the same matter-of-fact tone of voice. Stage Three: 9. Open comments. Thanks The reference book: The power of a positive no - William Ury. It is the will, with its freedom to choose, which determines the direction and destiny of each individual life. This is the truth which needs to be made plain for every youth, adult and child. If all could understand the crucial role of personal choice and the consequences of making the wrong decision, millions of souls might be turned from darkness to light. -

Negotiation and Conflict Management

United States Institute of Peace Certificate Course in Negotiation and Conflict Management Produced by the Education & Training Center/International For the most recent version of this course, please visit: www.usip.org/training/online Copyright © 2010 Endowment for the United States Institute of Peace Chapter 1: Introduction About the Course This Certificate Course in Negotiation and Conflict Management is the second self-study course in a series that includes our Certificate Course in Conflict Analysis and Certificate Course in Interfaith Conflict Resolution, and will include courses in mediation and other elements of conflict management—all available online. Our Certificate Course in Conflict Analysis is the first in the series, and we strongly recommend that you take it prior to taking this course. Effective action is invariably the product of insightful analysis. The Certificate Course in Negotiation and Conflict Management is the second course in the series because negotiation is a fundamental skill for anyone practicing conflict management and peacebuilding, perhaps the most important tool in a practitioner’s toolkit. It informs other skills, such as mediation, and can be crucial to effectiveness at any point in the life cycle of a conflict. Certificate of Completion Throughout the course you will be prompted to test your understanding of terms and concepts. When the course is complete, you will have the opportunity to take a course exam. When you pass the exam, you will earn our Certificate of Completion in this negotiation course. 1.1: An Alternative to Violence Protest Against Injustice On March 21, 1960, in the township of Sharpeville, South Africa, police opened fire on a large but peaceful protest, killing and wounding scores of unarmed demonstrators. -

Bliss, Donald T

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR DONALD T. BLISS Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: November 21st, 2013 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1941 B.A. Principia College, 1963 J.D. Harvard Law School, 1966 Entered the Peace Corps Volunteer in Micronesia, 1966-1968 Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) 1969-1973 Executive Secretary under the Honorable Elliot L. Richardson Department of Transportation 1973 Special Assistant (S-3) to Secretary of Transportation William (Bill) T. Coleman II U.S. Agency for International Development 1974-1975 Executive Secretary U.S. Department of Transportation 1975-1976 General Counsel Partner at O’Melveny and Myers LLP 1977-2006 Chair of Aviation and Transport American Bar Association (ABA) 1999-2001 Chair of the Air and Space Law Forum International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Council 2006-2009 Appointed by George W. Bush as Permanent U.S. Representative to ICAO, held rank of Ambassador United National Association-National Capital Area 2009-2013 President of the UNA-NCA, 1 Retired (2013) INTERVIEW Q: Today is the 21st of November, 2013 with Ambassador Donald T. Bliss, B-L-I-S-S, and this is being done on behalf of the Association of Diplomatic Studies and Training. And I’m Charles Stuart Kennedy. And you go by Don. BLISS: Right. Q: All right, let’s start at the beginning. Where and when were you born? BLISS: I was born on November 24, 1941 in Norwalk, Connecticut. Q: OK. Let’s get a little family background. -

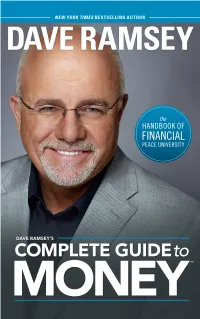

Dave Ramsey's Complete Guide to Money: the Handbook

DAVE RAMSEY’S COMPLETE GUIDE TO MONEY The Handbook of Financial Peace University Peace Philippians 4:7 © 2011 Lampo Licensing, LLC Published by Lampo Press, The Lampo Group, Inc. Brentwood, Tennessee 37027 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The Dave Ramsey Show, Total Money Makeover, Financial Peace, Financial Peace University, and Dave Ramsey are all registered trademarks of Lampo Licensing, LLC. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations noted nkjv are from the New King James Version®. © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc., Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations noted niv 1984 are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTER- NATIONAL VERSION®. © 1984 Biblica. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations noted niv 2011 are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTER- NATIONAL VERSION®. © 2011 Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations noted nrsv are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible. © 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations noted cev are from the Contemporary English Version®. © 1995 by the American Bible Society. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations noted The Message are from The Message. © 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. -

Why Didn't Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NSU Works Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 3 1994 Article 7 Why Didn’t Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate Stephen E. Ambrose∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Ambrose: Why Didn't Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Waterga Why Didn't Nixon Bum the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate Stephen E. Ambrose* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 1775 II. WHY DID THEY BREAK IN? ........... 1776 III. WHO WAS DEEP THROAT? .......... .. 1777 IV. WHY DIDN'T NIXON BURN THE TAPES? . 1778 V. VICE PRESIDENT FORD AND THE PARDON ........ 1780 I. INTRODUCTION For almost two years, from early 1973 to September, 1974, Watergate dominated the nation's consciousness. On a daily basis it was on the front pages-usually the headline; in the news magazines-usually the cover story; on the television news-usually the lead. Washington, D.C., a town that ordinarily is obsessed by the future and dominated by predictions about what the President and Congress will do next, was obsessed by the past and dominated by questions about what Richard Nixon had done and why he had done it. Small wonder: Watergate was the political story of the century. Since 1974, Watergate has been studied and commented on by reporters, television documentary makers, historians, and others. These commentators have had an unprecedented amount of material with which to work, starting with the tapes, the documentary record of the Nixon Administration, other material in the Nixon Presidential Materials Project, plus the transcripts of the various congressional hearings, the courtroom testimony of the principal actors, and the memoirs of the participants.