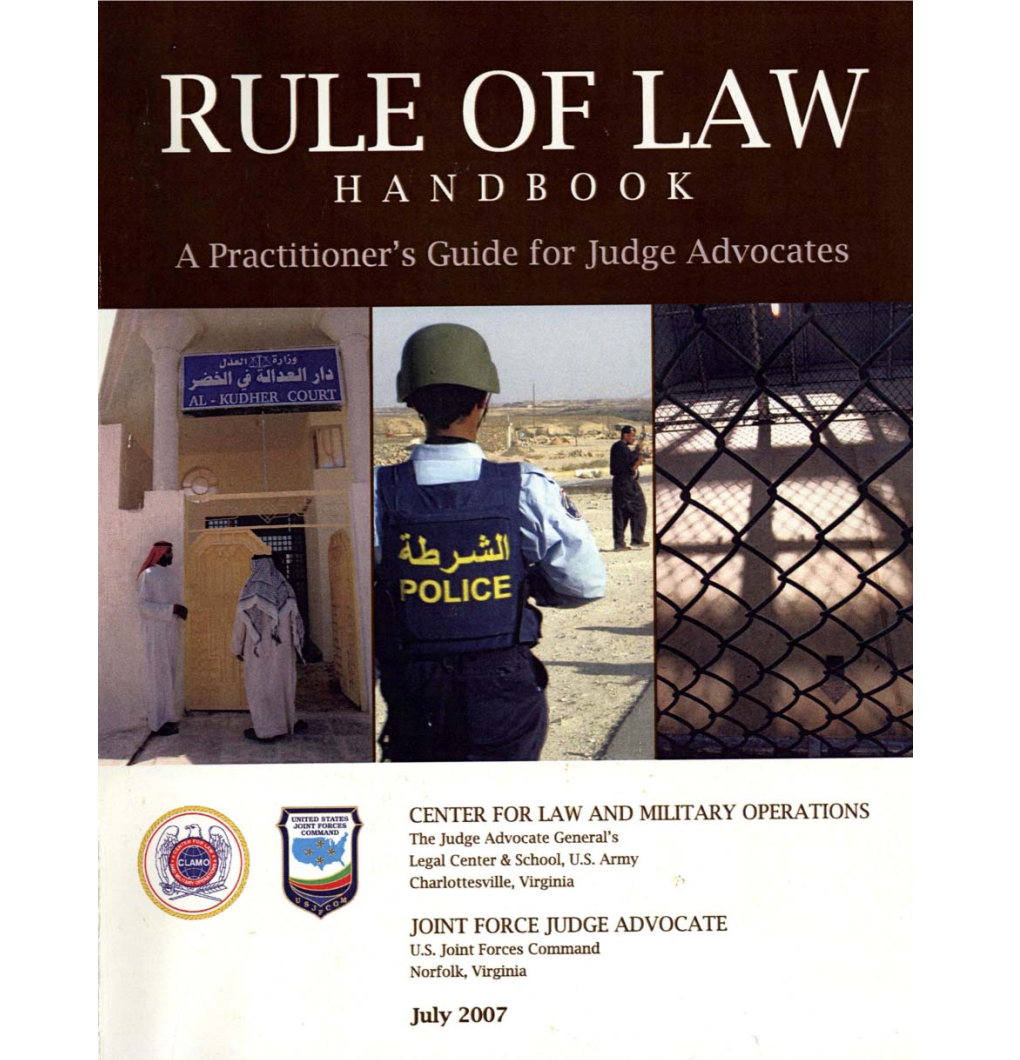

Rule of Law Handbook a Practitioner's Guide for Judge Advocates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USAID Legal Empowerment of the Poor

LEGAL EMPOWERMENT OF THE POOR: FROM CONCEPTS TO ASSESSMENT MARCH 2007 This publicationLAND AND was BUSINESS produced FORMALIZATION for review FOR by LEGAL the United EMPOWE StatesRMENT Agency OF THE POOR: for STRATEGIC OVERVIEW PAPER 1 International Development. It was prepared by ARD, Inc. Legal Empowerment of the Poor: From Concepts to Assessment. Paper by John W. Bruce (Team Leader), Omar Garcia-Bolivar, Tim Hanstad, Michael Roth, Robin Nielsen, Anna Knox, and Jon Schmidt Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, Contract Number EPP-0- 00-05-00015-00, UN High Commission – Legal Empowerment of the Poor, under Global - Man- agement, Organizational and Business Improvement Services (MOBIS). Implemented by: ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, VT 05401 Cover Photo: Courtesy of USAID. At a village bank in Djiguinoune, Senegal, women line up with account booklets and monthly savings that help secure fresh loans to fuel their small businesses. LEGAL EMPOWERMENT OF THE POOR FROM CONCEPTS TO ASSESSMENT MARCH 2007 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................... iii 1.0 DEFINING LEGAL EMPOWERMENT OF THE POOR .....................................................1 2.0 SUBSTANTIVE DIMENSIONS OF LEGAL EMPOWERMENT .........................................5 -

Legal Awareness in the Context of Professional Activities of Law Enforcement Officers: Specificity of Interference

ФІЛОСОФСЬКІ ТА МЕТОДОЛОГІЧНІ ПРОБЛЕМИ ПРАВА, № 1, 2014 Polischuk P. V. adjunct of department of philosophy of right and legal logic of the National academy of internal affairs LEGAL AWARENESS IN THE CONTEXT OF PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS: SPECIFICITY OF INTERFERENCE. The article presents the philosophical and legal analysis of occupational justice and law enforcement police officers. The essence and specific professional conscience were considered. It was defined its role in the process of enforcement. It was analyzed the features of mutual sense of justice and professional activities of law enforcement staff. Keywords: law, legal awareness, professional awareness, activity, law application activity. The peculiarities of interconnection between legal awareness and professional activity of law enforcement representatives Modern globalization processes in the world fasten and complicate the dynamics of social relations. As a result a system of legal regulation gets a big amount of problems. One of the most important matters is effectiveness assurance and efficiency of law protection activity. Its importance is evident. Internal affairs representatives during their professional activity perform a great number of functions connected with security interest, law enforcement, defense of rights and legal interests of subjects. Definite attention should be paid towards the influence of professional awareness on process and results of law enforcement activity. This influence is dual. Such specification will help to avoid one-side impressions about possible methods and efficiency in law enforcement activity. The latest events in Ukrainian society made us understand that insufficient level of professional consciousness and legal culture is a very important problem. The consequences are the following: low or even absent prestige of personnel, negative people’s attitude towards police, inadequate coherence between internal affairs bodies and community, etc. -

The Cracked Colonial Foundations of a Neo-Colonial Constitution

1 THE CRACKED COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS OF A NEO-COLONIAL CONSTITUTION Klearchos A. Kyriakides This working paper is based on a presentation delivered at an academic event held on 18 November 2020, organised by the School of Law of UCLan Cyprus and entitled ‘60 years on from 1960: A Symposium to mark the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus’. The contents of this working paper represent work in progress with a view to formal publication at a later date.1 A photograph of the Press and Information Office, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of Cyprus, as reproduced on the Official Twitter account of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus, 16 August 2018, https://twitter.com/cyprusmfa/status/1030018305426432000 ©️ Klearchos A. Kyriakides, Larnaca, 27 November 2020 1 This working paper reproduces or otherwise contains Crown Copyright materials and other public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0, details of which may be viewed on the website of the National Archives of the UK, Kew Gardens, Surrey, at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernment-licence/version/3/ This working paper also reproduces or otherwise contains British Parliamentary Copyright material and other Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence, details of which may be viewed on the website of the Parliament of the UK at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/ 2 Introduction This working paper has one aim. It is to advance a thesis which flows from a formidable body of evidence. At the moment when the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus (‘the 1960 Constitution’) came into force in the English language at around midnight on 16 August 1960, it stood on British colonial foundations, which were cracked and, thus, defective. -

Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: in Brief

Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: In Brief Christopher M. Blanchard Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Amy Belasco Specialist in U.S. Defense Policy and Budget January 9, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43727 Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: In Brief Summary The FY2015 continuing appropriations resolution (P.L. 113-164, H.J.Res. 124, FY2015 CR), enacted on September 19, 2014, authorized the Department of Defense (DOD) through December 11, 2014, or until the passage of a FY2015 national defense authorization act (NDAA), to provide overt assistance, including training, equipment, supplies, and sustainment, to vetted members of the Syrian opposition and other vetted Syrians for select purposes. The FY2015 NDAA (P.L. 113- 291, H.R. 3979) and the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235, H.R. 83) provide further authority and funding for the program. Congress acted in response to President Obama’s request for authority to begin such a program as part of U.S. efforts to combat the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations in Syria and to set the conditions for a negotiated settlement to Syria’s civil war. The FY2015 measures authorize DOD to submit reprogramming requests to the four congressional defense committees to transfer available funds. DOD submitted the first such reprogramming request in November 2014 under authorities provided by P.L. 113-164, and, in December, Congress approved $220 million in requested funds to begin program activities. H.R. 83 states that up to $500 million of $1.3 billion made available by the act for a new Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF) may be used to support the Syria train and equip program. -

Report on the Rule Of

Strasbourg, 4 April 2011 CDL-AD(2011)003rev Study No. 512 / 2009 Or. Engl. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) REPORT ON THE RULE OF LAW Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 86 th plenary session (Venice, 25-26 March 2011) on the basis of comments by Mr Pieter van DIJK (Member, Netherlands) Ms Gret HALLER (Member, Switzerland) Mr Jeffrey JOWELL (Member, United Kingdom) Mr Kaarlo TUORI (Member, Finland) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2011)003rev - 2 - Table of contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 II. Historical origins of Rule of law, Etat de droit and Rechtsstaat.................................. 3 III. Rule of law in positive law ......................................................................................... 5 IV. In search of a definition ............................................................................................. 9 V. New challenges....................................................................................................... 13 VI. Conclusion .............................................................................................................. 13 Annex: Checklist for evaluating the state of the rule of law in single states ......................... 15 - 3 - CDL-AD(2011)003rev I. Introduction 1. The concept of the “Rule of Law”, along with democracy and human rights,1 makes up the three -

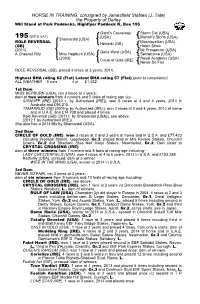

J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195 Giant's Causeway Storm Cat (USA) 195 (WITH VAT) (USA) Mariah's Storm (USA) Shamardal (USA) ROLE REVERSA L Machiavellian (USA) Helsinki (GB) (GB) Helen Street (2011) Mr Prospector (USA) Gone West (USA) A Chesnut Filly Miss Hepburn (USA) Secrettame (USA) (2003) Royal Academy (USA) Circle of Gold (IRE) Never So Fair ROLE REVERSAL (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 62 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 57 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 5 runs 4 pl £1,532 1st Dam MISS HEPBURN (USA), ran 3 times at 2 years; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SIGNOFF (IRE) (2010 c. by Authorized (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years, 2014 in Australia and £96,215. TAMARRUD (GB) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2013 at home and in U.A.E. and £14,738 and placed 4 times. Role Reversal (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), see above. (2012 f. by Authorized (IRE)). She also has a 2013 filly by Shamardal (USA). 2nd Dam CIRCLE OF GOLD (IRE) , won 3 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £77,423 including Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 , placed third in Mrs Revere Stakes, Churchill Downs, Gr.2 and Shadwell Stud Nell Gwyn Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3 ; Own sister to CRYSTAL CROSSING (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- LADY CHESTERFIELD (USA) , won 4 races at 4 to 6 years, 2013 in U.S.A. -

The Legal Empowerment Movement and Its Implications

THE LEGAL EMPOWERMENT MOVEMENT AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Peter Chapman* Around the world, a global legal empowerment movement is transforming the way in which people access justice. The concept of legal empowerment is rooted in strengthening the ability of communities to: “understand, use and shape the law.”1 The movement relies on people helping one another to stand up to authority and challenge injustice. At its center are paralegals, barefoot lawyers, and community advocates. Backed up by lawyers, these advocates are having significant impacts. Legal empowerment advocates employ a range of tools driven by the communities with which they work, including information, organizing, advocacy, and litigation. They take on issues including problems of health care, violations of consumer rights, threats to personal safety, environmental contamination, and challenges to property rights. Legal empowerment advocates tackle individual cases but a key objective of legal empowerment is systemic change. Informed by expanding evidence of need,2 buoyed by regulatory innovation,3 and in response to local activism, civil society organizations and government institutions are embracing the notion that people who are not trained as lawyers can competently help people assess their rights and resolve their legal problems. In South Africa, an independent network of Community Advice Offices is expanding legal awareness and mobilizing collective * Thanks to Matthew Burnett, Open Society Justice Initiative, Maha Jweied, and David Udell, National Center for Access to Justice, for their inputs and perspectives in framing this piece. 1. See NAMATI, https://namati.org/ [https://perma.cc/SSX4-GRDA] (last visited Apr. 1, 2019). 2. See LEGAL SERVS. CORP., 2017 JUSTICE GAP REPORT (2017), https://www.lsc.gov/ sites/default/files/images/TheJusticeGap-FullReport.pdf [https://perma.cc/X5E9-CZE3]; Our Work, WORLD JUST. -

Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security Updated March 29, 2006 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom succeeded in overthrowing Saddam Hussein, but Iraq remains violent and unstable because of Sunni Arab resentment and a related insurgency, as well as growing sectarian violence. According to its November 30, 2005, “Strategy for Victory,” the Bush Administration indicates that U.S. forces will remain in Iraq until the country is able to provide for its own security and does not serve as a host for radical Islamic terrorists. The Administration believes that, over the longer term, Iraq will become a model for reform throughout the Middle East and a partner in the global war on terrorism. However, mounting casualties and costs — and growing sectarian conflict — have intensified a debate within the United States over the wisdom of the invasion and whether to wind down U.S. involvement without completely accomplishing U.S. goals. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is showing important successes, demonstrated by two elections (January and December 2005) that chose an interim and then a full-term National Assembly, a referendum that adopted a permanent constitution (October 15, 2005), progress in building Iraq’s security forces, and economic growth. While continuing to build, equip, and train Iraqi security units, the Administration has been working to include more Sunni Arabs in the power structure, particularly the security institutions; Sunnis were dominant during the regime of Saddam Hussein but now feel marginalized by the newly dominant Shiite Arabs and Kurds. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8 5 9 5 10

NAKAYAMA SUNDAY,OCTOBER 4TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1200m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:6Dec.09 1:10.2 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Tomoyuki Nakamura 770,000 S 20002 Life40004M 20002 1 1 B 55.0 Yuichiro Nishida(0.8%,1−2−4−121,133rd) Turf40004 I 00000 Maradona(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 .Pelusa(0.05) .Kane Hekili C2,ch. Takaki Iwato(4.9%,11−20−10−183,113rd) Course00000E 00000 Wht. /Maradona Spin /Bambina Coco 23Feb.18 Bamboo Stud Wet 00000 2Aug.20 NIIGATA MDN T1200Fi 11 13 1:11.8 18th/18 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468' Nishino Adjust 1:10.1 <3/4> Tosen Gaia <1/2> Meiner Amistad 19Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1200Fi 7 6 1:11.3 4th/11 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468% Seiun Deimos 1:10.2 <2 1/2> Longing Birth <4> High Priestess 5Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1800Yi 45310 1:54.0 11th/11 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466' Cosmo Ashura 1:50.2 <NK> Magical Stage <NK> Seiun Gold 20Jun.20 TOKYO NWC T1400Go 4 4 1:24.9 7th/16 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466* Cool Cat 1:23.4 <2> Songline <1 1/4> Bisboccia Ow. Toshio Isobe 0 S 20002 Life20002M 00000 1 2 53.0 Akira Sugawara(4.5%,18−25−31−324,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 Isoei Hikari(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 .A Shin Hikari(0.54) .South Vigorous C2,b. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., Ph.D. – C.V

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., PH.D. (203) 809-8500 • ZACHARY . KAUFMAN @ AYA . YALE. EDU • WEBSITE • SSRN ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS SCHOOL OF LAW (Jan. – May 2022) Visiting Associate Professor of Law UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LAW CENTER (July 2019 – present) Associate Professor of Law and Political Science (July 2019 – present) Co-Director, Criminal Justice Institute (Aug. 2021 – present) Affiliated Faculty Member: • University of Houston Law Center – Initiative on Global Law and Policy for the Americas • University of Houston Department of Political Science • University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs • University of Houston Elizabeth D. Rockwell Center on Ethics and Leadership STANFORD LAW SCHOOL (Sept. 2017 – June 2019) Lecturer in Law and Fellow EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD – D.Phil. (Ph.D.), 2012; M.Phil., 2004 – International Relations • Marshall Scholar • Doctoral Dissertation: From Nuremberg to The Hague: United States Policy on Transitional Justice o Passed “Without Revisions”: highest possible evaluation awarded o Examiners: Professors William Schabas and Yuen Foong Khong o Supervisors: Professors Jennifer Welsh (primary) and Henry Shue (secondary) o Adaptation published (under revised title) by Oxford University Press • Master’s Thesis: Explaining the United States Policy to Prosecute Rwandan Génocidaires YALE LAW SCHOOL – J.D., 2009 • Editor-in-Chief, Yale Law & Policy Review • Managing Editor, Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal • Articles Editor, Yale Journal of International Law