Student Contributions to a National Ethnography of Brunei from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal by Nikolas Sweet a Dissertation Submitte

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal By Nikolas Sweet A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee Professor Judith Irvine, chair Associate Professor Michael Lempert Professor Mike McGovern Professor Barbra Meek Professor Derek Peterson Nikolas Sweet [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3957-2888 © 2019 Nikolas Sweet This dissertation is dedicated to Doba and to the people of Taabe. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field work conducted for this dissertation was made possible with generous support from the National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the University of Michigan Rackham International Research Award. Many thanks also to the financial support from the following centers and institutes at the University of Michigan: The African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, Rackham Graduate School, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, the Mellon Institute, and the International Institute. I wish to thank Senegal’s Ministère de l'Education et de la Recherche for authorizing my research in Kédougou. I am deeply grateful to the West African Research Center (WARC) for hosting me as a scholar and providing me a welcoming center in Dakar. I would like to thank Mariane Wade, in particular, for her warmth and support during my intermittent stays in Dakar. This research can be seen as a decades-long interest in West Africa that began in the Peace Corps in 2006-2009. -

EALC Newsletter 2017-2018

East Asian Languages & Civilizations News and Updates From Academic Year 2017 - 2018 From the Chair Friends and Colleagues: In This Issue We are so happy to be sending the inaugural newsletter of the Department of East Asian Language and Civilizations. As the more than 3 Faculty Profiles seventy faculty and alumni who were at the EALC lunch during the annual meeting of the Association of Asian Studies in Washington, D.C., now know, 10 Faculty Bookshelf we are a very different department from the one many of you remember. 12 Associated Faculty In 2002, eight faculty members boldly and ambitiously became Penn’s first Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. We are a small 15 Student Prizes department with a huge vision: we seek to offer undergraduates the stongest, most diverse, and most rigorous education available in the East Asian 16 Chinese Language Program Humanities in North America; we seek to train Ph. D. students who become 18 Japanese Language Program the intellectual leaders in the East Asian Humanities in future generations; and we have crafted a vibrant masters program in which students with career 20 Korean Language Program ambitions from entry into Ph. D. programs to employment in the public or private sector, government service, and education are poised to accomplish 22 Van Pelt Library those goals. 24 Graduate Student Highlights Striving to prepare students for careers that span this century, we have reconfigured ourselves in four streams: China, Korea, Japan, and Inner 26 Body and Cosmos Asia. Every major and every graduate students trains in at least two of these areas, undergraduates and MA students through course requirements and Ph. -

PMW Tutong District

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for December, 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Bukit Udal, Mukim Tanjong Maya 1 Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Bukit Udal Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 2 Kampong Long Mayan, Mukim Ukong Tutong Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Long Mayan Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar, Mukim Tanjong Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Penapar, Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar and 3 Maya Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm surrounding area. Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau, Pertanian Birau Office and surrounding 4 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm area. Monday Perumahan Baitul Mal Keriam, Mukim Keriam A whole of Perumahan Baitul Mal, a part of Kampong Keriam and 5 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. 3rd Dec 2018 Tutong. surrounding area. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Serambangun, Mukim Tanjong Maya A whole Spg 333-37-39-16 Kampong Serambangun and 6 Wayleave Clearing 4th Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong. surrounding areas. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau and Pertanian Birau Office and 7 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. -

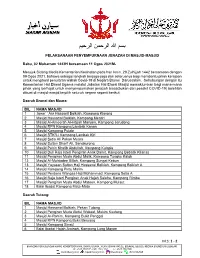

Perlaksanaan Pengurusan Jenazah Di

مﺳﺑ ﷲ نﻣﺣرﻟا مﯾﺣرﻟا PELAKSANAAN PENYEMPURNAAN JENAZAH DI MASJID-MASJID Rabu, 02 Muharram 1443H bersamaan 11 Ogos 2021M- Merujuk Sidang Media Kementerian Kesihatan pada hari Isnin, 29 Zulhijjah 1442 bersamaan dengan 09 Ogos 2021, bahawa sebagai langkah berjaga-jaga dan seterusnya bagi membantu pihak kerajaan untuk mengawal penularan wabak Covid-19 di Negara Brunei Darussalam. Sehubungan dengan itu Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama melalui Jabatan Hal Ehwal Masjid memaklumkan bagi mana-mana pihak yang berhajat untuk menyempurnakan jenazah biasa(bukan dari pesakit COVID-19) bolehlah dibuat di masjid-masjid terpilih seluruh negara seperti berikut; Daerah Brunei dan Muara: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Jame’ ‘ Asr Hassanil Bolkiah, Kampong Kiarong 2 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Mentiri 3 Masjid Al-Ameerah Al-Hajjah Maryam, Kampong Jerudong 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Lambak Kanan 5 Masjid Kampong Pulaie 6 Masjid STKRJ Kampong Lambak Kiri 7 Masjid Setia Ali Pekan Muara 8 Masjid Sultan Sharif Ali, Sengkurong 9 Masjid Pehin Khatib Abdullah, Kampong Kulapis 10 Masjid Duli Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Damit, Kampong Bebatik Kilanas 11 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Malik, Kampong Tungku Katok 12 Masjid Al-Muhtadee Billah, Kampong Sungai Kebun 13 Masjid Yayasan Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Bolkiah A 14 Masjid Kampong Pintu Malim 15 Masjid Perdana Wangsa Haji Mohammad, Kampong Setia A 16 Masjid Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajah Saleha, Kampong Rimba 17 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Mateen, Kampong Mulaut 18 Balai Ibadat Kampong Mata-Mata Daerah Tutong: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Pekan Tutong 2 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Wakeel, Mukim Kiudang 3 Masjid Ar-Rahim, Kampong Bukit Penggal 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Bukit Beruang 5 Masjid Kampong Sinaut 6 Balai Ibadat Hajah Aminah, Kampong Long Mayan M.S: 1 - 2 _ BAHAGIAN PERHUBUNGAN AWAM, KEMENTERIAN HAL EHWAL UGAMA, JALAN DEWAN MAJLIS, BERAKAS, BB3910, NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM. -

Maritime Indonesia and the Archipelagic Outlook Some Reflections from a Multidisciplinary Perspective on Old Port Cities in Java

Multamia R.M.T. WacanaLauder Vol. and 17 Allan No. 1 (2016): F. Lauder 97–120, Maritime Indonesia 97 Maritime Indonesia and the Archipelagic Outlook Some reflections from a multidisciplinary perspective on old port cities in Java Multamia R.M.T. Lauder and Allan F. Lauder Abstract The present paper reflects on Indonesia’s status as an archipelagic state and a maritime nation from a historical perspective. It explores the background of a multi-year research project into Indonesia’s maritime past currently being undertaken at the Humanities Faculty of Universitas Indonesia. The multidisciplinary research uses toponymy, epigraphy, philology, and linguistic lines of analysis in examining old inscriptions and manuscripts and also includes site visits to a number of old port cities across the archipelago. We present here some of the core concepts behind the research such as the importance of the ancient port cities in a network of maritime trade and diplomacy, and link them to some contemporary issues such as the Archipelagic Outlook. This is based on a concept of territorial integrity that reflects Indonesia’s national identity and aspirations. It is hoped that the paper can extend the discussion about efforts to make maritime affairs a strategic geopolitical goal along with restoring Indonesia’s identity as a maritime nation. Allan F. Lauder is a guest lecturer in the Post Graduate Linguistics Department program at the Humanities Faculty of the Universitas Indonesia. Allan obtained his MA in the English Language at the Department of English Language and Literature, National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore, 1988 – 1990 and his Doctorate Degree in Applied Linguistics, English Language at Atma Jaya University. -

8/14/2010 Pelitabrunei Nama-Nama Amil Keluaran 14 Ogos Pelita1

2 HARI SABTU 14 OGOS 2010 ZAKAT FITRAH BAGI TAHUN 1431H BERSAMAAN 2010M SENARAI NAMA-NAMA AMIL BAGI SELURUH NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BAGI TAHUN 1431-1432H / 2010-2011M BIL KAWASAN NAMA AMIL TEMPAT MEMBAYAR KERAMAIAN AMIL-AMIL DAN KAWASAN-KAWASAN BAGI SELURUH 31. Jalan Tasek Lama hingga NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BAGI TAHUN 1431 - 1432H / 2010 - 2011M Terrace Hotel 32. Jalan Stoney Yang Mulia, Mudim Awang KERAMAIAN AMIL 33. Jalan Dato Ibrahim Haji Amran bin Haji Mohd. JABATAN / DAERAH KAWASAN 34. Jalan Istana Darussalam Salleh JABATAN MAJLIS UGAMA ISLAM 29 ORANG 4 35. Kg. Pengiran Pemanca Lama 36. Kg. Sungai Kedayan A dan B Masjid Omar 163 ORANG BRUNEI / MUARA 75 37. Kg. Kianggeh dan Sekitarnya 'Ali Saifuddien BELAIT 27 ORANG 15 38. Kg. Ujong Tanjong 39. Kg. Kuala Sg. Peminyak Yang Mulia, Mudim Awang TUTONG 55 ORANG 30 40. Kg. Ujong Bukit Haji Ahmad Kasra bin Haji 41. Kg. Limbongan Ibrahim TEMBURONG 17 ORANG 12 42. Kg. Bukit Salat JUMLAH 291 ORANG 136 43. Kg. Sumbiling Lama Yang Mulia Ustaz Haji Adanan Surau Ibu Pejabat SENARAI NAMA-NAMA AMIL JABATAN MAJLIS UGAMA ISLAM Balai Bomba Bandar Seri Begawan bin Haji Ahmad Perkhidmatan Bomba 2. Brunei (Khas untuk Pegawai dan (Ketua Guru Agama Jabatan dan Penyelamat, BAGI TAHUN 1431-1432H / 2010-2011M Kakitangan serta keluarganya) Perkhidmatan Bomba dan Lapangan Terbang Penyelamat) Lama Berakas, Brunei BIL LANTIKAN ATAS NAMA JAWATAN BIL LANTIKAN ATAS NAMA BATANG TUBUH 2. BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN 'B' mengandungi: BIL KAWASAN NAMA AMIL TEMPAT MEMBAYAR 1. Setiausaha Majlis Ugama Islam, Brunei 1. Awang Haji Abd. Wahab bin Haji Sapar (Awang Haji Harun bin Haji Junid) (Pegawai Ugama Kanan Kumpulan 2) Awang Haji Ahmad bin Haji 2. -

Employment and Skills Strategies in Southeast Asia Setting the Scene

Employment and Skills Strategies in Southeast Asia Setting the Scene Cristina Martinez-Fernandez and Marcus Powell E MPLOYMENT and S KILLS S TRATEGIES in S OUTHEAST A SIA 2 – ABOUT THE REPORT About the ESSSA Initiative The initiative on Employment and Skills Strategies in Southeast Asia (ESSSA) facilitates the exchange of experiences on employment and skills development. Its objectives are to guide policymakers in the design of policy approaches able to tackle complex cross-cutting labour market issues; to build the capacity of practitioners in implementing effective local employment and skills development strategies; and to assist in the development of governance mechanisms conducive to policy integration and partnership at the local level. For more information on the ESSSA initiative please visit https://community.oecd.org/community/esssa. About the OECD The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a unique forum where the governments of 30 market democracies work together to address the economic, social and governance challenges of globalisation as well as to exploit its opportunities. The OECD’s way of working consists of a highly effective process that begins with data collection and analysis and moves on to collective discussion of policy, then decision-making and implementation. Mutual examination by governments, multilateral surveillance and peer pressure to conform or reform are at the heart of OECD effectiveness. Much of the material collected and analysed at the OECD is published on paper or online; from press releases and regular compilations of data and projections to one-time publications or monographs on particular issues; from economic surveys of each member country to regular reviews of education systems, science and technology policies or environmental performance. -

PMW Tutong District (Press Release) Memo25

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for October and November , 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Kampong Lubuk Ubar, Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 1 Jln Kuru-Benutan, Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Lubuk Ubar and surrounding area. 16th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.00 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong Tuesday Kampong Sebakit Atas, Mukim Tanjong Maya 2 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. Spg 49 Kampong Sebakit Atas and surrounding area. 16th Oct 2018 tutong Wednesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 3 Wayleave Clearing 17th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong area. Wednesday Kampong Sulap Samat, Jalan Panchong, Mukim A part of Kampong Sulap Samat, Jln Panchong and surrounding 4 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. 17th Oct 2018 Lamunin area. Thursday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 5 Wayleave Clearing 18th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong area. Thursday 6 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Kampong Penabai, Mukim Pekan Tutong Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. A part of Kampong Penabai and surrounding area. 18th Oct 2018 Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 7 Mukim Rambai, Tutong Wayleave Clearing 20th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm area. -

PMW Tutong District

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for October , 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Maintenance works for low voltage overhead 1 08th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kampong Padnunuk, Mukim Kiudang, Tutong lines. A part of Jln Kecil Padnunuk , Jln Andaru and surrounding area. Monday Hospital Pengiran Muda Mahkota Pengiran Muda Maintenance works for Distribution 2 08th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah, Tutong Transformer#3. A part of Hospital Building and the surrrounding area. Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 3 08th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kg Ukong, Mukim Ukong Wayleave Clearing for overhead lines A part of Kg Ukong and the surrrounding area. Tuesday Maintenance works for Distribution 4 09th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Earth Satellite, Telisai, Tutong. Transformer#1. Earth satellite Building and the surrounding area. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Maintenance works for low voltage overhead 5 09th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kampong Padnunuk, Mukim Kiudang, Tutong, lines. Jln Andaru, a part of Jln Kecil Padnunuk and surrounding areas. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 6 09th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kg Ukong, Mukim Ukong Wayleave Clearing for overhead lines A part of Kg Ukong and the surrrounding area. Wednesday Maintenance works for Distribution 7 10th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Earth Satellite, Telisai, Tutong. -

Persidangan Dewan Majlis

PAGI HARI KHAMIS, 2 RABIULAKHIR 1431 / 18 MAC 2010 206 DEWAN MAJLIS Khamis, 2 Rabiulakhir 1431 / 18 Mac 2010 YANG DI-PERTUA Duli Yang Teramat Mulia DAN AHLI-AHLI MAJLIS Paduka Seri Pengiran Muda Mahkota MESYUARAT NEGARA Pengiran Muda Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah ibni Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri HADIR: Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah, DKMB., DPKT., YANG DI-PERTUA: King Abdul Aziz Ribbon, First Class (Saudi Arabia), The Order of the Renaissance (First Yang Amat Mulia Degree) (Jordan), Medal of Honour (Lao), Pengiran Indera Mahkota Pengiran Anak DSO (Singapore), Order of Lakandula with (Dr.) Kemaludin Al-Haj ibni Al-Marhum the Rank of Grand Cross (Philippines), DSO Pengiran Bendahara Pengiran Anak Haji (Military) (Singapore), PHBS., Mohd. Yassin, PSLJ., SPMB., POAS., Menteri Kanan di Jabatan Perdana Menteri, PHBS., PBLI., PJK., PKL., Negara Brunei Darussalam. Yang Di-Pertua , Negara Brunei Darussalam. Duli Yang Teramat Mulia Paduka Seri Pengiran Perdana Wazir AHLI-AHLI RASMI KERANA JAWATAN Sahibul Himmah Wal-Waqar Pengiran (PERDANA MENTERI DAN MENTERI- Muda Mohamed Bolkiah ibni Al-Marhum MENTERI): Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien, DKMB., DK., PHBS., PBLI., Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia PJK., Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Menteri Hal Ehwal Luar Negeri dan Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Perdagangan, Negara Brunei Darussalam. Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien, Sultan dan Yang Yang Berhormat Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam, Pehin Orang Kaya Seri Lela Dato Seri Setia Perdana Menteri, Menteri Pertahanan dan Haji Awang Abdul Rahman bin Dato Setia Menteri Kewangan, Negara Brunei Haji Mohamed Taib, PSNB., SLJ., PHBS., Darussalam. -

Bismarck, ND 58501; 701-255-6000 Or

75th Annual Plains Anthropological Conference Bismarck, North Dakota October 4-7, 2017 Conference Host: State Historical Society of North Dakota (http://history.nd.gov) Conference Committee State Historical Society of North Dakota: • Amy C. Bleier • Wendi Field Murray • Timothy A. Reed • Fern E. Swenson Staff – State Historical Society of North Dakota: • Claudia Berg • Guinn Hinman • Lorna Meidinger • Brooke Morgan • Amy Munson • Paul Picha • Susan Quinnell • Toni Reinbold • Meagan Schoenfelder • Lisa Steckler • Richard Fisk and Museum Store Thank you Chris Johnston, Treasurer of the Plains Anthropological Society, for your invaluable support and assistance. Conference Logo: The logo of the 75th Annual Plains Anthropological Conference is drawn from a decorated pottery vessel in the On-A-Slant Village archaeological collection. The collection is curated at the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck. 1 The State Historical Society of North Dakota thanks our conference partners: 2 CONFERENCE VENDORS & EXHIBITS • Anthropology Department, University of Wyoming • Arikara Community Action Group • Beta Analytic, Inc. • Center for Applied Isotope Studies – University of Georgia • John Bluemle, Geologist & Author • KLJ • Archaeophysics LLC • National Park Service • Nebraska Association of Professional Archeologists • Nebraska State Historical Society • North Dakota Archaeological Association • Plains Anthropologist, Journal of the Plains Anthropological Society • St. Cloud State University • SWCA Environmental Consultants • THG Geophysics • Wichita State University 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 GENERAL INFORMATION Conference Headquarters: All conference events, except for the guided tours on Wednesday and Saturday and the reception on Thursday evening, will be held at the Radisson Hotel Bismarck (605 East Broadway Avenue, Bismarck, ND 58501; 701-255-6000 or https://www.radisson.com/bismarck-hotel-nd-58501/ndbisdt). -

Buku Poskod Edisi Ke 2 (Kemaskini 26122018).Pdf

Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pada bahgian hadapan sampul surat:- RAJAH PERTAMA PENGGUNAAN MUKA HADAPAN SAMPUL SURAT 74 MM 40 MM Ruangan untuk kegunaan pengirim Ruangan untuk alamat penerima Ruangan 20 MM untuk kegunaan Pejabat Pos 20 MM 140 MM Lebar Panjang Ukuran minimum 90 mm 140 mm Ukuran maksimum 144 mm 264 mm Bagi surat yang dikirim melalui pos, alamat pengirim hendaklah ditulis pada bahagian penutup belakang sampul surat. Ini membolehkan surat berkenaan dapat dikembalikan kepada pengirim sekiranya surat tersebut tidak dapat diserahkan kepada si penerima seperti yang dikehendaki. Disamping itu. ianya juga menolong penerima mengenal pasti alamat dan poskod awda yang betul. Dengan cara ini penerima akan dapat membalas surat awda dengan alamat dan poskod yang betul. Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pengirim pada bahagian penutup sampul surat:- RAJAH DUA Jabatan Perkhidmatan Pos berhasrat memberi perkhidmatan yang efesien kepada awda. Oleh itu, kerjasama awda sangat-sangat diperlukan. Adalah menjadi tugas awda mempastikan ketepatan maklumat-maklumat alamat dan poskod awda kerana ianya merupakan kunci bagi kecepatan penyerahan surat awda GARIS PANDU SKIM POSKOD NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Y Z 0 0 0 0 Kod Daerah Kod Mukim Kod Kampong / Kod Pejabat Kawasan Penyerahan Contoh: Y Menunjukan Kod Daerah Z Menunjukan Kod Mukim 00 Menunjukan Kod Kampong/Kawasan 00 Menunjukan Kod Pejabat Penyerahan KOD DAERAH BIL Daerah KOD 1. Daerah Brunei Muara B 2. Daerah Belait K 3. Daerah Tutong T 4. Daerah Temburong P POSKOD BAGI KEMENTERIAN- KEMENTERIAN