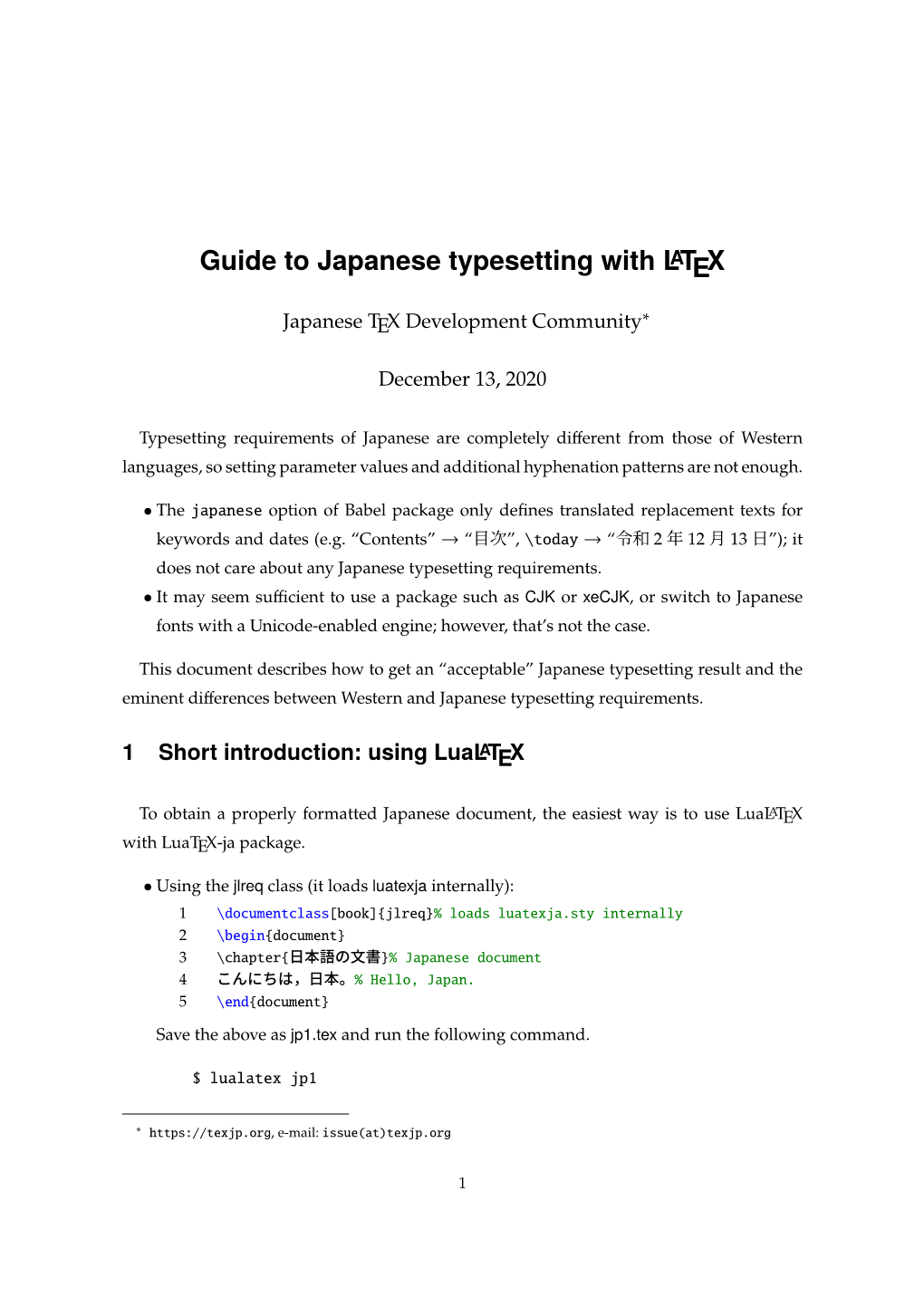

Guide to Japanese Typesetting with LATEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Method to Accommodate Backward Compatibility on the Learning Application-Based Transliteration to the Balinese Script

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2021 A Method to Accommodate Backward Compatibility on the Learning Application-based Transliteration to the Balinese Script 1 3 4 Gede Indrawan , I Gede Nurhayata , Sariyasa I Ketut Paramarta2 Department of Computer Science Department of Balinese Language Education Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha (Undiksha) Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha (Undiksha) Singaraja, Indonesia Singaraja, Indonesia Abstract—This research proposed a method to accommodate transliteration rules (for short, the older rules) from The backward compatibility on the learning application-based Balinese Alphabet document 1 . It exposes the backward transliteration to the Balinese Script. The objective is to compatibility method to accommodate the standard accommodate the standard transliteration rules from the transliteration rules (for short, the standard rules) from the Balinese Language, Script, and Literature Advisory Agency. It is Balinese Language, Script, and Literature Advisory Agency considered as the main contribution since there has not been a [7]. This Bali Province government agency [4] carries out workaround in this research area. This multi-discipline guidance and formulates programs for the maintenance, study, collaboration work is one of the efforts to preserve digitally the development, and preservation of the Balinese Language, endangered Balinese local language knowledge in Indonesia. The Script, and Literature. proposed method covered two aspects, i.e. (1) Its backward compatibility allows for interoperability at a certain level with This study was conducted on the developed web-based the older transliteration rules; and (2) Breaking backward transliteration learning application, BaliScript, for further compatibility at a certain level is unavoidable since, for the same ubiquitous Balinese Language learning since the proposed aspect, there is a contradictory treatment between the standard method reusable for the mobile application [8], [9]. -

Speaker Biographies

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Speakers: Dr. Deborah Anderson, Researcher, Dept. of Linguistics, UC Berkeley Deborah (Debbie) Anderson is a Researcher in the Department of Linguistics at UC Berkeley. Since 2002, she has run the Script Encoding Initiative project, which helps get scripts and characters into the Unicode Standard. She also represents UC Berkeley in the Unicode Technical Committee meetings and is a member of the US National Body in ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2. In addition, she is a Unicode Technical Director. Zibi Braniecki, Mozilla, Sr. Staff Platform Engineer Zibi Braniecki is a Sr. Staff Platform Engineer at Mozilla working on internationalization and localization of Gecko and Firefox. Zibi represents Mozilla at TC39 committee and is championing multiple ECMA402 proposals. When not in front of the keyboard, he's captaining the Polish National Team in Ultimate Frisbee. Shane Carr, Senior Software Engineer, Internationalization, Google, Inc. Shane Carr is a Senior Software Engineer on Google's i18n Engineering team. He is chair of the ECMA 402 subcommittee for JavaScript i18n standards and is a core contributor to the International Components for Unicode (ICU) project. His work on ICU has focused on locale data, number formatting, and performance optimization. Shane has previously presented on Zawgyi and on ICU number formatting at the 41st and 42nd Internationalization & Unicode Conference (IUC). He has also presented at the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) and the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE). He holds an MS and BS in Computer Science and BS in Chemical Engineering summa cum laude from Washington University in St. -

4.4. Is Unicode Font Available? 14 4.4.1

1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 1.1. Who we are 3 1.2. The UNESCO and IYIL initiative 4 2. Process overview 4 2.1. Language Status Workflow 5 2.2. Technology Implementation Workflow 6 3. Language Status 7 3.1. Is language currently used by a community? 7 3.2. Is language intended for active community use? 7 3.2.1. Revitalize language 7 3.3. Is language in a public registry? 8 3.4. Is language written? 8 3.4.1. Develop written form 8 3.4.2. Document language 8 3.4.2.1. Language is documented 8 3.4.2.2. Language is not documented 9 3.5. Does language use a consistent writing system? 9 3.5.1. Are the characters used already supported? 9 3.6. Is writing supported by a standard? 10 3.6.1. Submit character proposals 10 3.6.2. Develop standard 11 3.7. Proceed to implementation 11 4. Language Technology Implementation Workflow 11 4.1 Note on technology for text in digital systems 11 4.2. Definitions for implementing digital support 12 4.3. Standard language code available? 13 4.3.1. Apply for language code 13 4.4. Is Unicode font available? 14 4.4.1. Create font 14 4.5. Is font available on devices? 14 4.5.1. Manual install or ask vendors for support 14 4.6. Does device have input support? 15 4.7. Is input supported by third party apps or devices? 15 4.7.1. Develop input method 15 4.8. Does device have Unicode data support? 16 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License 2 5. -

Referência Debian I

Referência Debian i Referência Debian Osamu Aoki Referência Debian ii Copyright © 2013-2021 Osamu Aoki Esta Referência Debian (versão 2.85) (2021-09-17 09:11:56 UTC) pretende fornecer uma visão geral do sistema Debian como um guia do utilizador pós-instalação. Cobre muitos aspetos da administração do sistema através de exemplos shell-command para não programadores. Referência Debian iii COLLABORATORS TITLE : Referência Debian ACTION NAME DATE SIGNATURE WRITTEN BY Osamu Aoki 17 de setembro de 2021 REVISION HISTORY NUMBER DATE DESCRIPTION NAME Referência Debian iv Conteúdo 1 Manuais de GNU/Linux 1 1.1 Básico da consola ................................................... 1 1.1.1 A linha de comandos da shell ........................................ 1 1.1.2 The shell prompt under GUI ......................................... 2 1.1.3 A conta root .................................................. 2 1.1.4 A linha de comandos shell do root ...................................... 3 1.1.5 GUI de ferramentas de administração do sistema .............................. 3 1.1.6 Consolas virtuais ............................................... 3 1.1.7 Como abandonar a linha de comandos .................................... 3 1.1.8 Como desligar o sistema ........................................... 4 1.1.9 Recuperar uma consola sã .......................................... 4 1.1.10 Sugestões de pacotes adicionais para o novato ................................ 4 1.1.11 Uma conta de utilizador extra ........................................ 5 1.1.12 Configuração -

Pdflib-9.3.1-Tutorial.Pdf

ABC PDFlib, PDFlib+PDI, PPS A library for generating PDF on the fly PDFlib 9.3.1 Tutorial For use with C, C++, Java, .NET, .NET Core, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, RPG, Ruby Copyright © 1997–2021 PDFlib GmbH and Thomas Merz. All rights reserved. PDFlib users are granted permission to reproduce printed or digital copies of this manual for internal use. PDFlib GmbH Franziska-Bilek-Weg 9, 80339 München, Germany www.pdflib.com phone +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-0 [email protected] [email protected] (please include your license number) This publication and the information herein is furnished as is, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib GmbH assumes no responsibility or lia- bility for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind (express, implied or statutory) with re- spect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for par- ticular purposes and noninfringement of third party rights. PDFlib and the PDFlib logo are registered trademarks of PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib licensees are granted the right to use the PDFlib name and logo in their product documentation. However, this is not required. PANTONE® colors displayed in the software application or in the user documentation may not match PANTONE-identified standards. Consult current PANTONE Color Publications for accurate color. PANTONE® and other Pantone, Inc. trademarks are the property of Pantone, Inc. © Pantone, Inc., 2003. Pantone, Inc. is the copyright owner of color data and/or software which are licensed to PDFlib GmbH to distribute for use only in combination with PDFlib Software. -

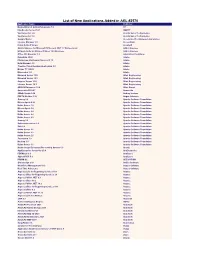

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2570

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2570 Application Name Publisher Nomad Branch Admin Extensions 7.0 1E FineReader Server 14.1 ABBYY VoxConverter 2.0 Acarda Sales Technologies VoxConverter 3.0 Acarda Sales Technologies Sample Master Accelerated Technology Laboratories License Manager 3.5 AccessData Prizm ActiveX Viewer AccuSoft Add-in Express for Microsoft Office and .NET 7.7 Professional Add-in Express Ultimate Suite for Microsoft Excel 18.5 Business Add-in Express Office 365 Reporter 3.5 AdminDroid Solutions RoboHelp 2020 Adobe Photoshop Lightroom Classic CC 10 Adobe Help Manager 4.0 Adobe Creative Cloud Desktop Application 5.3 Adobe Bridge CC (2021) Adobe Dimension 3.4 Adobe Monarch Server 15.0 Altair Engineering Monarch Server 15.3 Altair Engineering Angoss Server 10.4 Altair Engineering License Server 14.1 Altair Engineering ARGUS Enterprise 12.0 Altus Group Anaconda 2020.07 Anaconda SMath Studio 0.98 Andrey Ivashov PDFTK Builder 3.10 Angus Johnson Groovy 2.6 Apache Software Foundation Mesos Agent 0.28 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 1.0 Apache Software Foundation Mesos Agent 1.8 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.4 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.6 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.3 Apache Software Foundation Groovy 2.5 Apache Software Foundation Subversion server 1.9 Apache Software Foundation Solr 2.0 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.1 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.2 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.5 Apache Software Foundation Cassandra 3.9 Apache Software Foundation -

Pdflib Tutorial 9.2.0

ABC PDFlib, PDFlib+PDI, PPS A library for generating PDF on the fly PDFlib 9.2.0 Tutorial For use with C, C++, COM, Java, .NET, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, RPG, Ruby Copyright © 1997–2019 PDFlib GmbH and Thomas Merz. All rights reserved. PDFlib users are granted permission to reproduce printed or digital copies of this manual for internal use. PDFlib GmbH Franziska-Bilek-Weg 9, 80339 München, Germany www.pdflib.com phone +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-0 If you have questions check the PDFlib mailing list and archive at groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/pdflib/info Licensing contact: [email protected] Support for commercial PDFlib licensees: [email protected] (please include your license number) This publication and the information herein is furnished as is, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib GmbH assumes no responsibility or lia- bility for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind (express, implied or statutory) with re- spect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for par- ticular purposes and noninfringement of third party rights. PDFlib and the PDFlib logo are registered trademarks of PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib licensees are granted the right to use the PDFlib name and logo in their product documentation. However, this is not required. PANTONE® colors displayed in the software application or in the user documentation may not match PANTONE-identified standards. Consult current PANTONE Color Publications for accurate color. PANTONE® and other Pantone, Inc. trademarks are the property of Pantone, Inc. -

Google Fonts Download Free

google fonts download free Are Google Fonts Free for Commercial Use? The simple answer is yes, all the fonts included in the Google Fonts library are released under licenses that allow you to use them for free, in both commercial and personal applications. The open source fonts in the Google Fonts catalog are published under licenses that allow you to use them on any website, whether it’s commercial or personal. https://developers.google.com/fonts/faq. More specifically, the fonts use one of three license types: All three licenses place very little restrictions on how you can use the fonts. The primary restrictions are based around redistribution. A key requirement is that if you distribute the fonts, you must also include the original license files. You must give any other recipients of the Work or Derivative Works a copy of this License; and You must cause any modified files to carry prominent notices stating that You changed the files; and You must retain, in the Source form of any Derivative Works that You distribute, all copyright, patent, trademark, and attribution notices from the Source form of the Work, excluding those notices that do not pertain to any part of the Derivative Works; and http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0. It’s also important to not distribute modified versions using the original name: Google Sans Font Free Download. Google sans is a sans-serif typeface that has a humanist classification. Steve Matteson, an American designer, designed this beautiful font many years ago along with many other noted typefaces. -

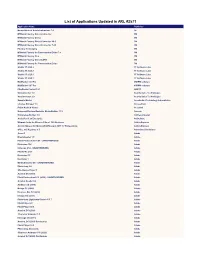

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2571

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2571 Application Name Publisher Nomad Branch Admin Extensions 7.0 1E M*Modal Fluency Direct Connector 3M M*Modal Fluency Direct 3M M*Modal Fluency Direct Connector 10.0 3M M*Modal Fluency Direct Connector 7.85 3M Fluency for Imaging 3M M*Modal Fluency for Transcription Editor 7.6 3M M*Modal Fluency Flex 3M M*Modal Fluency Direct CAPD 3M M*Modal Fluency for Transcription Editor 3M Studio 3T 2020.2 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2020.8 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2020.3 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2020.7 3T Software Labs MailRaider 3.69 Pro 45RPM software MailRaider 3.67 Pro 45RPM software FineReader Server 14.1 ABBYY VoxConverter 3.0 Acarda Sales Technologies VoxConverter 2.0 Acarda Sales Technologies Sample Master Accelerated Technology Laboratories License Manager 3.5 AccessData Prizm ActiveX Viewer AccuSoft Universal Restore Bootable Media Builder 11.5 Acronis Knowledge Builder 4.0 ActiveCampaign ActivePerl 5.26 Enterprise ActiveState Ultimate Suite for Microsoft Excel 18.5 Business Add-in Express Add-in Express for Microsoft Office and .NET 7.7 Professional Add-in Express Office 365 Reporter 3.5 AdminDroid Solutions Scout 1 Adobe Dreamweaver 1.0 Adobe Flash Professional CS6 - UNAUTHORIZED Adobe Illustrator CS6 Adobe InDesign CS6 - UNAUTHORIZED Adobe Fireworks CS6 Adobe Illustrator CC Adobe Illustrator 1 Adobe Media Encoder CC - UNAUTHORIZED Adobe Photoshop 1.0 Adobe Shockwave Player 1 Adobe Acrobat DC (2015) Adobe Flash Professional CC (2015) - UNAUTHORIZED Adobe Acrobat Reader DC Adobe Audition CC (2018) -

Release Notes for Fedora 21

Fedora 21 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 21 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2014 Fedora Project Contributors. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

TUGBOAT Volume 40, Number 2 / 2019 TUG 2019 Conference

TUGBOAT Volume 40, Number 2 / 2019 TUG 2019 Conference Proceedings TUG 2019 98 Conference sponsors, participants, program, photos 101 Henri Menke / Back to the roots: TUG 2019 in Palo Alto 104 Jennifer Claudio / TEX Users Group 2019 Annual General Meeting notes General Delivery 106 Jim Hefferon / What do today’s newcomers want? Software & Tools 108 Tomas Rokicki / Type 3 fonts and PDF search in dvips 112 Arthur Reutenauer / The state of X TE EX 113 Arthur Reutenauer / Hyphenation patterns: Licensing and stability 115 Richard Koch / MacTEX-2019, notification, and hardened runtimes 126 Uwe Ziegenhagen / Combining LATEX with Python 119 Didier Verna / Quickref: Common Lisp reference documentation as a stress test for Texinfo 129 Henri Menke / Parsing complex data formats in LuaTEX with LPEG Methods 136 William Adams / Design into 3D: A system for customizable project designs Electronic Documents 143 Martin Ruckert / The design of the HINT file format 147 Rishikesan Nair T., Rajagopal C.V., Radhakrishnan C.V. / TEXFolio — a framework to typeset XML documents using TEX 150 Aravind Rajendran, Rishikesan Nair T., Rajagopal C.V. / Neptune — a proofing framework for LATEX authors LATEX 153 Frank Mittelbach / The LATEX release workflow and the LATEX dev formats 157 Chris Rowley, Ulrike Fischer, Frank Mittelbach / Accessibility in the LATEX kernel — experiments in Tagged PDF 159 Boris Veytsman / Creating commented editions with LATEX—the commedit package 163 Uwe Ziegenhagen / Creating and automating exams with LATEX & friends Bibliographies 167 Sree -

Mupdf Explored

MuPDF Explored Robin Watts July 30, 2021 Preface This is the beginnings of a book on MuPDF. It is far from complete, but offers useful information as far as it goes. We offer it with the latest release of MuPDF (currently 1.13) in the hopes it will be useful. Any feedback, corrections or suggestions are welcome. Please visit bugs. ghostscript.com and open a bug with \MuPDF" as the product, and \Docu- mentation" as the component. We will endeavour to make new versions available from the Documentation section of mupdf.com as they appear. i Acknowledgements Many thanks are due to Tor Andersson for creating MuPDF, to everyone who has contributed to it over the years, and to all my colleagues at Artifex Software for providing an environment in which it could grow, and nursing it through to maturity. Particular thanks are due to Sebastian Rasmussen for patiently proof-reading the book through its many revisions, and suggesting numerous improvements. Finally, many thanks are due to Helen Rogers, for putting up with me. ii Contents Prefacei Acknowledgements ii 1 Introduction1 1.1 What is MuPDF?...........................1 1.2 License.................................1 1.3 Dependencies.............................3 2 About this book5 I The MuPDF C API6 3 Quick Start7 3.1 How to open a document and render some pages.........7 4 Naming Conventions8 4.1 Prefixes................................8 4.2 Naming................................8 4.3 Types................................. 10 5 The Context 11 5.1 Overview............................... 11 5.2 Creation................................ 12 5.3 Custom Allocators.......................... 13 5.4 Multi-threading............................ 13 5.5 Cloning................................ 15 5.6 Destruction.............................