The Stock Market and the Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Labor Force Experience of Women from 'Generation X'

Women from ‘‘Generation X' The labor force experience of women from ‘Generation X’ Women aged 25 to 34 years in 2000 participated in the labor force in greater proportions, were more educated, earned more, and generally enjoyed more labor market benefits than their counterparts 25 years earlier; moreover, the “earnings gap” between young women and men narrowed substantially over the period Marisa DiNatale uring the 1960s and 1970s, legislation years had completed 4 or more years of col- and and changing social mores dramatically lege, compared with 18 percent 25 years Stephanie Boraas Daltered the choices young women had earlier. about their futures. Girls growing up during this • Young women have substantially closed period were influenced both by the conventions the “earnings gap” with their male coun- of their parents’ generation and by the new op- terparts since 1979 (the first year for which portunities that were becoming available to them. comparable earnings data are available In contrast, girls born in later years grew up in an from the CPS). They earned 82 percent as era in which women often were expected to com- much as young men in 2000 for full-time bine market work1 with family responsibilities. work, compared with 68 percent in 1979. Consequently, women who were aged 25 to 34 years in 2000 had a markedly different relation- • Married women aged 25 to 34 years—par- ship to the labor market than did their counter- ticularly those who had children—were far parts in 1975. more likely to be in the labor force in 2000 The first part of this article focuses on the than 25 years earlier. -

1. D) Amendments to Articles 34 and 55 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization Geneva, 22 May 1973 .ENTRY INTO

1. d) Amendments to articles 34 and 55 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization Geneva, 22 May 1973 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 3 February 1977, in accordance with article 73 of the Constitution, for all members of the World Health Organization*. REGISTRATION: 3 February 1977, No. 221. STATUS: Parties* TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 1035, p. 315. Note: The amendments to articles 34 and 55 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization were adopted by the Twenty-sixth World Health Assembly by resolution WHA 26.37 of 22 May 1973. In accordance with article 73 of the Constitution, amendments come into force for all Members when adopted by a two- thirds vote of the Health Assembly and accepted by two-thirds of the Members in accordance with their respective constitutional processes. Following is the list of States which had accepted the amendments prior to the entry into force of the Amendments. *See chapter IX.1 for the complete list of Participants, Members of the World Health Organization, for which the above amendments are in force, pursuant to article 73 of the Constitution. Participant1 Acceptance(A) Participant1 Acceptance(A) Afghanistan..................................................28 Feb 1975 A El Salvador ..................................................17 Oct 1975 A Argentina ..................................................... 4 Oct 1976 A Eswatini .......................................................18 Nov 1975 A Australia.......................................................11 Mar 1975 A Ethiopia....................................................... -

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Jan 1963 $17,200 (NA) Feb 1963 $17,700 (NA) Mar 1963 $18,200 (NA) Apr 1963 $18,200 (NA) May 1963 $17,500 (NA) Jun 1963 $18,000 (NA) Jul 1963 $18,400 (NA) Aug 1963 $17,800 (NA) Sep 1963 $17,900 (NA) Oct 1963 $17,600 (NA) Nov 1963 $18,400 (NA) Dec 1963 $18,700 (NA) Jan 1964 $17,800 (NA) Feb 1964 $18,000 (NA) Mar 1964 $19,000 (NA) Apr 1964 $18,800 (NA) May 1964 $19,300 (NA) Jun 1964 $18,800 (NA) Jul 1964 $19,100 (NA) Aug 1964 $18,900 (NA) Sep 1964 $18,900 (NA) Oct 1964 $18,900 (NA) Nov 1964 $19,300 (NA) Dec 1964 $21,000 (NA) Jan 1965 $20,700 (NA) Feb 1965 $20,400 (NA) Mar 1965 $19,800 (NA) Apr 1965 $19,900 (NA) May 1965 $19,600 (NA) Jun 1965 $19,800 (NA) Jul 1965 $21,000 (NA) Aug 1965 $20,200 (NA) Sep 1965 $19,600 (NA) Oct 1965 $19,900 (NA) Nov 1965 $20,600 (NA) Dec 1965 $20,300 (NA) Jan 1966 $21,200 (NA) Feb 1966 $20,900 (NA) Mar 1966 $20,800 (NA) Apr 1966 $23,000 (NA) May 1966 $22,300 (NA) Jun 1966 $21,200 (NA) Jul 1966 $21,800 (NA) Aug 1966 $20,700 (NA) Sep 1966 $22,200 (NA) Oct 1966 $20,800 (NA) Nov 1966 $21,700 (NA) Dec 1966 $21,700 (NA) Jan 1967 $22,200 (NA) Page 1 of 13 Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Feb 1967 $22,400 (NA) Mar 1967 $22,400 (NA) Apr 1967 $22,300 (NA) May 1967 $23,700 (NA) Jun 1967 $23,900 (NA) Jul 1967 $23,300 (NA) Aug 1967 $21,700 (NA) Sep 1967 $22,800 (NA) Oct 1967 $22,300 (NA) Nov 1967 $23,100 (NA) Dec 1967 $22,200 (NA) Jan 1968 $23,400 (NA) Feb 1968 $23,500 (NA) Mar 1968 -

Adam Smith 1723 – 1790 He Describes the General Harmony Of

Adam Smith 1723 – 1790 He describes the general harmony of human motives and activities under a beneficent Providence, and the general theme of “the invisible hand” promoting the harmony of interests. The invisible hand: There are two important features of Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand”. First, Smith was not advocating a social policy (that people should act in their own self interest), but rather was describing an observed economic reality (that people do act in their own interest). Second, Smith was not claiming that all self-interest has beneficial effects on the community. He did not argue that self-interest is always good; he merely argued against the view that self- interest is necessarily bad. It is worth noting that, upon his death, Smith left much of his personal wealth to churches and charities. On another level, though, the “invisible hand” refers to the ability of the market to correct for seemingly disastrous situations with no intervention on the part of government or other organizations (although Smith did not, himself, use the term with this meaning in mind). For example, Smith says, if a product shortage were to occur, that product’s price in the market would rise, creating incentive for its production and a reduction in its consumption, eventually curing the shortage. The increased competition among manufacturers and increased supply would also lower the price of the product to its production cost plus a small profit, the “natural price.” Smith believed that while human motives are often selfish and greedy, the competition in the free market would tend to benefit society as a whole anyway. -

1 Three Essential Questions of Production

Three Essential Questions of Production ~ Economic Understandings SS7E5a Name_______________________________________Date__________________________________ Class 1 2 3 4 Traditional Economies Command Economies Market Economies Mixed Economies What is In this type of In a command economy, the In a market economy, the Nearly all economies in produced? economic system, what central government decides wants of the consumers and the world today have is produced is based on what goods and services will the profit motive of the characteristics of both custom and the habit be produced, what wages will producers will decide what market and command of how such decisions be paid to workers, what will be produced. A.K.A. economic systems. were made in the past. jobs the workers do, as well Free-enterprise, Laisse- as the prices of goods. faire & capitalism. This means that most How is it The methods of In a command economy, no Labor (the workers) and countries have produced? production are one can start their own management (the characteristics of a primitive. Bartering, or business. bosses/owners) together free market/free a system of trading in The government determines will determine how goods enterprise as well as goods and services, how and where the goods will be produced in a market some government replaces currency in a produced would be sold. economy. planning and control. traditional economy. For whom is The primary group for In a command economy, the In a market economy, each it produced? whom goods and government determines how production resource is paid services are produced the goods and services are based on what is in a traditional economy distributed. -

Sahara Occidental Western Sahara

COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRÊTS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES SAHARA OCCIDENTAL (REQUÊTE POUR AVIS CONSULTATIF) ORDONNANCE DU 22 MAI 1975 INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS WESTERN SAHARA (REQUEST FOR ADVISORY OPINION) ORDER OF 22 MAY 1975 Mode officiel de citation: Sahara occidental, ordonnance du 22 mai 1975, C.I.J. Reclieil 1975, p. 6. Official citation : Western Sahara, Order of 22 May 1975, I.C.J. Reports 1975, p. 6. sales numbe-41 1 No de vente: INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE YEAR 1975 1975 22 May 22 May 1975 General List No. 61 WESTERN SAHARA (REQUEST FOR ADVISORY OPINION) ORDER Present: President LACHS; Vice-President AMMOUN;Judges FORSTER, GROS,BENGZON, PETRÉN, ONYEAMA, DILLARD, IGNACIO-PINTO, DE CASTRO,MOROZOV, JIMÉNEZ DE ARÉCHAGA,Sir Humphrey WALDOCK,NAGENDRA SINGH, RUDA; Registrar AQUARONE. Composed as above, After deliberation, Having regard to Articles 31 and 68 of the Statute of the Court, and to Articles 3, 87 and 89 of the Rules of Court, Having regard to resolution 3292 (XXIX) of the General Assenibly of the United Nations dated 13 December 1974 requesting the International Court of Justice to give an advisory opinion on the following questions: "1. Was Western Sahara (Rio de Oro and Sakiet El Hamra) at the time of colonization by Spain a territory belonging to no one (terra nullius)? If the answer to the first question is in the negative, II. What were the legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritanian entity?" 4 Makes -

List of Technical Papers

Program Reports Report Title Copies Number Number 1: Program Prospectus. December 1963. 2 Program Design Report. February 1965. 2 Number 2: Supplement: 1968-1969 Work Program. February 1968. 1 Supplement: 1969-1970 Work Program. May 1969. 0 Number 3: Cost Accounting Manual. February 1965. 1 Number 4: Organizational Manual. February 1965. 2 Guide Plan: Central Offices for the Executive Branch of State Number 5: 2 Government. April1966. XIOX Users Manual for the IBM 7090/7094 Computer. November Number 6: 2 1966. Population Projections for the State of Rhode Island and its Number 7: 2 Municipalities--1970-2000. December 1966. Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space (Interim Report). Number 8: 2 February 1968. Rhode Island Transit Plan: Future Mass Transit Services and Number 9: 2 Facilities. June 1969. Plan for the Development and Use of Public Water Supplies. Number 10: 1 September 1969. Number 11: Plan for Public Sewerage Facility Development. September 1969. 2 Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space (Second Interim Number 12: 2 Report). May 1970. Number 13: Historic Preservation Plan. September 1970. 2 Number 14: Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space. January 1971. 2 Number 15: A Department of Transportation for Rhode Island. March 1971. 2 State Airport System Plan (1970-1990). Revised Summary Report. Number 16: 2 December 1974. Number 17: Westerly Economic Growth Center, Planning Study. February 1973. 1 Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space--Supplement. June Number 18: 2 1973. Number 19: Rhode Island Transportation Plan--1990. January 1975. 2 Number 20: Solid Waste Management Plan. December 1973. 2 1 Number 21: Report of the Trail Advisory Committee. -

Vanguard Economic and Market Outlook 2021: Approaching the Dawn

Vanguard economic and market outlook for 2021: Approaching the dawn Vanguard Research December 2020 ■ While the global economy continues to recover as we head into 2021, the battle between the virus and humanity’s efforts to stanch it continues. Our outlook for the global economy hinges critically on health outcomes. The recovery’s path is likely to prove uneven and varied across industries and countries, even with an effective vaccine in sight. ■ In China, we see the robust recovery extending in 2021 with growth of 9%. Elsewhere, we expect growth of 5% in the U.S. and 5% in the euro area, with those economies making meaningful progress toward full employment levels in 2021. In emerging markets, we expect a more uneven and challenging recovery, with growth of 6%. ■ When we peek beyond the long shadow of COVID-19, we see the pandemic irreversibly accelerating trends such as work automation and digitization of economies. However, other more profound setbacks brought about by the lockdowns and recession will ultimately prove temporary. Assuming a reasonable path for health outcomes, the scarring effect of permanent job losses is likely to be limited. ■ Our fair-value stock projections continue to reveal a global equity market that is neither grossly overvalued nor likely to produce outsized returns going forward. This suggests, however, that there may be opportunities to invest broadly around the world and across the value spectrum. Given a lower-for-longer rate outlook, we find it hard to see a material uptick in fixed income returns in the foreseeable future. Lead authors Vanguard Investment Strategy Group Vanguard Global Economics and Capital Markets Outlook Team Joseph Davis, Ph.D., Global Chief Economist Joseph Davis, Ph.D. -

Economic and Social Coun(

UNITED NATIONS Distr. ECONOMIC GENEML AND E/CN.4/1279 5 January'1978 SOCIAL COUN( Originals ENGLISH COMMISSION ON HUMN RIGHTS Thirty-fourth session Item 19 of the provisional agenda STATUS OP THE INTERlíATIONAL COVENANTS ON HUMâN RIGHTS Note Ъу the Secretary-General 1. At its thirty-third session, the Commission on Human Rights had before it a note by the Secretary-General (E/CN.4/1227) on the status of the International Covenant on Economic,"Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 2. In its resolution 2 (XXXIIl) of .18 February 1977 the Commission on Human Rights welcomed with deep satisfaction the entry into force of the International Covenant on Economic, - Social an.d Cultural Rights, the International Covenant.on Civil and Political Rights and the Optional Protocol to the latter Covenant. The Commission called upon all States to take legislative or other measures for the realization of the human rights and fundamental freedoms provided for in the Covenants, invited the States parties to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to consider making the declaration provided for in article 4I of that Covenant and requested the Secretary-General to continue to inform the Commission on Human Rights at each session of any new developments with regard to ratification and implemiontation of the International Covenants on Human Rights and the Optional Protocol. The present note was prepared in response to ..that request. 3. Before the adoption by the Commission of resolution 2(XXXIIl), Guyana had ratified both Covenants, on 15 February 1977, Since then, the two Covenants were ratified by Panama on 8 March 1977, Poland on 18 March 1977 and Spain on 27 April 1977. -

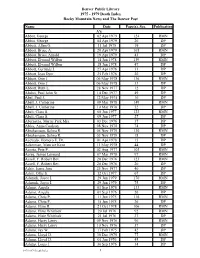

1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post Name Date Page(S), Sec

Denver Public Library 1975 - 1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post Name Date Page(s), Sec. Publication A's Abbot, George 02 Apr 1979 124 RMN Abbot, George 04 Apr 1979 26 DP Abbott, Allen G. 11 Jul 1975 19 DP Abbott, Bruce A. 20 Apr 1979 165 RMN Abbott, Bruce Arnold 19 Apr 1979 43 DP Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 14 Jun 1978 139 RMN Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 18 Jun 1978 47 DP Abbott, Gertrude J. 27 Apr 1976 31 DP Abbott, Jean Dyer 25 Feb 1976 20 DP Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 136 RMN Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 33 DP Abbott, Ruth L. 28 Nov 1977 12 DP Abdoo, Paul John Sr. 14 Dec 1977 49 DP Abel, Paul J. 12 May 1975 16 DP Abell, J. Catherine 09 Mar 1978 149 RMN Abell, J. Catherine 10 Mar 1978 52 DP Abelt, Clara S. 08 Jun 1977 123 RMN Abelt, Clara S. 09 Jun 1977 27 DP Abernatha, Martie Park Mrs. 03 Dec 1976 37 DP Ables, Anna Coulson 08 Nov 1978 74 DP Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 130 RMN Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 18 DP Acevedo, Homero E. Dr. 01 Apr 1978 15 DP Ackerman, Maurice Kent 11 May 1978 44 DP Acosta, Pete P. 02 Aug 1977 103 RMN Acree, Jessee Leonard 07 Mar 1978 97 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 123 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 20 DP Adair, Jense Jane 25 Nov 1977 40 DP Adair, Ollie S. -

Market Failure in Kidney Exchange†

American Economic Review 2019, 109(11): 4026–4070 https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180771 Market Failure in Kidney Exchange† By Nikhil Agarwal, Itai Ashlagi, Eduardo Azevedo, Clayton R. Featherstone, and Ömer Karaduman* We show that kidney exchange markets suffer from market failures whose remedy could increase transplants by 30 to 63 percent. First, we document that the market is fragmented and inefficient; most trans- plants are arranged by hospitals instead of national platforms. Second, we propose a model to show two sources of inefficiency: hospitals only partly internalize their patients’ benefits from exchange, and current platforms suboptimally reward hospitals for submitting patients and donors. Third, we calibrate a production function and show that indi- vidual hospitals operate below efficient scale. Eliminating this ineffi- ciency requires either a mandate or a combination of new mechanisms and reimbursement reforms. JEL D24, D47, I11 ( ) The kidney exchange market in the United States enables approximately 800 transplants per year for kidney patients who have a willing but incompatible live donor. Exchanges are organized by matching these patient–donor pairs into swaps that enable transplants. Each such transplant extends and improves the patient’s quality of life and saves hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical costs, ulti- mately creating an economic value estimated at more than one million dollars.1 Since monetary compensation for living donors is forbidden and deceased donors * Agarwal: Department of Economics, MIT, -

Power Market Economics LLC Evolving Capacity Markets in A

Power Market Economics LLC Evolving Capacity Markets in a Modern Grid By Robert Stoddard State policies in New England mandate substantial shifts in the generation resources serving their citizen’s electrical needs. Maine, for example, has a statutory requirement to shift to 80 percent renewables by 2030, with a goal of reaching 100 percent by 2050. Massachusetts’ Clean Energy Standard sets a minimum percentage of renewables at 16 percent in 2018, increasing 2 percentage points annually to 80 percent in 2050. Facing these sharp departures from business-as-usual, policymakers raise a core question: are today’s wholesale market designs able to help the states achieve these goals? Can they even accommodate these state policy resources? In particular, are today’s capacity markets—which are supposed to guide the long-term investment in electricity generation resources—up to the job? Capacity markets serve a central role in New England’s electricity market. They serve a critical role in helping to ensure that the system operator, ISO New England (ISO-NE), will have enough resources, located strategically on the grid, to meet expected peak loads with a sufficient reserve margin. How capacity markets are designed and operate has evolved relatively little since the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) launched the first full-fledged capacity market in 1999, the primary innovations being a longer lead-time in procurement of resources, better to support the orderly exit and construction of resources, and higher performance requirements, better to ensure that resources being paid to be available are in fact operating when needed. Are capacity markets now irrelevant? No.