Innovation and China's Global Emergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

会议详细议程(Final Program)

会议详细议程(Final Program) 2019 International Conference on Display Technology March 26th—29th, 2019 (Tuesday - Friday) Kunshan International Convention and Exhibition Center Kunshan, Suzhou, China Plenary Session Wednesday, Mar. 27/14:00—18:00/Reception Hall Chair: Shintson Wu (吴诗聪), University of Central Florida (UCF) Title: Laser display Technology (14:00-14:30) Zuyan Xu (许祖彦), Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, China Academy of Engineering (CAE) Title: Thin film transistor technology and applications (14:30-15:00) Ming Liu (刘明), Institute of Microelectronics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Title: Technology creates a win-win future (15:00-15:30) Wenbao Gao (高文宝), BOE Title: Gallium nitride micro-LEDs: a novel multi-mode, high-brightness and fast-response display technology (15:30-16:00) Martin Dawson, the University of Strathclyde’s Institute of Photonics, the Fraunhofer Centre for Applied Photonics Title: Virtual and Augmented Reality: Hope or Hype? (16:00-16:30) Achin Bhowmik, Starkey Hearing Technologies Title: Monocular Vision Impact: Monocular 3D and AR Display and Depth Detection with Monocular Camera (16:30-17:00) Haruhiko Okumura, Media AI Lab, Toshiba Title: ePaper, The Most Suitable Display Technology in AIoT (17:00-17:30) Fu-Jen (Frank) Ko, E Ink Holdings Inc. Title: Application Advantage of Laser Display in TV Market and Progress of Hisense (17:30- 18:00) Weidong Liu (刘卫东), Hisense Thursday, Mar. 28/8:30—12:30/Reception Hall Chair: Hoi S. Kwok (郭海成), Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Title: High Performance Tungsten-TADF OLED Emitters (8:30-9:00) Chi-Ming CHE (支志明), The University of Hong Kong Title: Challenges of TFT Technology for AMOLED Display (9:00-9:30) Junfeng Li (李俊峰), Nanyang Technological University, Innovation Research Institute of Visionox Technology Co., Ltd. -

Organizational Evolution of China's Third-Front Enterprises Shows Obvious Punctuated Equilibrium

Organizational Evolution of China’s Third-front Enterprises: Cases Study on Aosheng Group GUO Dong Thesis submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of Doctor of Management Supervisor: Professor Henriques Duarte, Assistant Professor, ISCTE University Institute of Lisbon Co-supervisor: Professor JING Runtian, Professor, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, School of Management and Economics May, 2013 - Spine – a’s Third-front Enterprises: GUO Dong Cases Study on Aosheng Group Organizational Evolution of Chin Organizational Evolution of China’s Third-front Enterprises: Cases Study on Aosheng Group GUO Dong Thesis submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of Doctor of Management Supervisor: Professor Henriques Duarte, Assistant Professor, ISCTE University Institute of Lisbon Co-supervisor: Professor JING Runtian, Professor, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, School of Management and Economics May, 2013 Declaration I declare that this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university and that to the best of my knowledge it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. Signed Date _________________ Name: _____________ 作者申明 本人郑重申明:除了论文致谢中明确说明并致以谢意的部分外,所呈交的论文不 包含任何他人或作者本人已用于获得任何教育机构的学位和证书而使用过的材 料。同时尽我所知,除了文中特别加以标注引用的内容外,本论文不包含任何其 他个人或集体已经发表或撰写的成果作品。 作者签名: 日期: 姓名(拼音) Abstract China's "Third-front" enterprises emerged in a specific historical period and specific institutional environment and played an important role in China's national defense construction and Chinese history. Due to changes in the world political and economic situations and domestic economic development, the development of Third-front companies face many challenges: support from central government have changed; they can’t depend only on government and military orders; need to face market-competition. -

Master's Degree Programme

Master’s Degree programme in Lingue, economie e istituzioni dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis The Evolving Framework of Chinese Outbound M&A The case of Inter Supervisor Ch. Prof. Renzo Riccardo Cavalieri Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Franco Gatti Graduand Valentina Coccato 841509 Academic Year 2016/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 前言 ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: China’s Outbound M&A ............................................................................... 10 1.1 Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment ............................................................ 10 1.2 Government role and regulations .............................................................................. 14 1.3 Policymaking actors .................................................................................................. 16 1.3.1 Top Level ............................................................................................................ 16 1.3.2 Second level ........................................................................................................ 17 1.3.3 Third level ........................................................................................................... 18 1.3.4 Fourth level ......................................................................................................... 20 1.4 OFDI Approval Procedure: A Changing Framework ............................................... -

Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment In

Reviews Mao’s War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, by Judith Shapiro, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2001), xvii, 287 pp. Reviewed by Gregory A. Ruf, Associate Professor, Chinese Studies and Anthropology Stony Brook State University of New York In this engaging and informative book, Judith Shapiro takes a sharp, critical look at how development policies and practices under Mao influenced human relationships with the natural world, and considers some consequences of Maoist initiatives for the environment. Drawing on a variety of sources, both written and oral, she guides readers through an historical overview of major political and economic campaigns of the Maoist era, and their impact on human lives and the natural environment. This is a bold and challenging task, not least because such topics remain political sensitive today. Yet the perspective Shapiro offers is refreshing, while the problems she highlights are disturbing, with significant legacies. The political climate of revolutionary China was pervaded by hostile struggle against class enemies, foreign imperialists, Western capitalists, Soviet revisionists, and numerous other antagonists. Under Mao and the communists, “the notion was propagated that China would pick itself up after its long history of humiliation by imperialist powers, become self-reliant in the face of international isolation, and regain strength in the world” (p.6). Militarization was to be a vehicle through which Mao would attempt to forge a ‘New China.’ His period of rule was marked by a protracted series of mass mobilization campaigns, based around the fear of perceived threats, external or internal. Even nature, Shapiro argues, was portrayed in a combative and militaristic rhetoric as an obstacle or enemy to overcome. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION VISTA PEAK VENTURES, LLC, Plaintiff, V

Case 2:18-cv-00433 Document 1 Filed 10/18/18 Page 1 of 21 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION VISTA PEAK VENTURES, LLC, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED § BOE TECHNOLOGY GROUP CO., LTD., § § CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:18-cv-433 Defendant. § § § § § § PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Vista Peak Ventures, LLC (“VPV”) files this Complaint against BOE Technology Group Co., Ltd. (“BOE”) for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 7,046,327 (“the ’327 patent”), U.S. Patent No. 6,870,593 (“the ’593 patent”), and U.S. Patent No. 6,812,528 (“the ’528 patent”), collectively, the “Asserted Patents.” THE PARTIES 1. Vista Peak Ventures, LLC is a Texas limited liability company, located at 1400 Preston Rd, Suite 472, Plano, TX 75093. 2. Upon information and belief, BOE was founded in April 1993 and provides “intelligent interface products and professional services for information interaction and human health.” See BOE Company Profile, (available at https://www.boe.com/en/about/gsjs/). BOE first issued “B shares” in foreign currency on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in 1997, and later issued “A shares” in the same exchange in 2001. See BOE Course of Development (available at https://www.boe.com/en/about/gsjs/). In its Company Profile, BOE lists its core businesses as PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT 1 Case 2:18-cv-00433 Document 1 Filed 10/18/18 Page 2 of 21 PageID #: 2 “Display and Sensor Devices, Smart Systems and Healthcare Services.” See BOE Company Profile. -

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Innovation and Upgrading Pathways in the Chinese Smartphone Production GVC Jiong How Lua National University of Singapore

Innovation and Upgrading pathways in the Chinese smartphone production GVC Lua Innovation and Upgrading pathways in the Chinese smartphone production GVC Jiong How Lua National University of Singapore Innovation and Upgrading pathways in the Chinese smartphone production GVC Lua Abstract This paper attends to the recent upgrading developments demonstrated by Chinese smartphone firms. Adopting a comparative approach of tearing down retail-accessible smartphones to their components, this paper traces the upgrading activities across global value chains (GVCs) that Chinese firms partake in during the production process. Upgrading is thus discovered to be diverse and complicated rather than a linear process, carrying significant implications for the production networks and supply chains in Chinese smartphone firms. Innovation and Upgrading pathways in the Chinese smartphone production GVC Lua Introduction China today is not only the world’s largest exporter of labor-intensive goods but also remains as the largest producer of personal electronics devices, surpassing the output of the US (West & Lansang, 2018). Contrary to popular belief, Chinese smartphone producers do not merely mimic their competitors, instead, innovate to “catch-up” with international competitors by upgrading across Global Value Chains (GVCs). Utilizing Liu et al. ’s (2015) illustration as a starting point, I open the dossier for both acknowledgement and critique. Figure 1. Two different expectations, two sources of mobile phone manufacturing Source: Liu et al. (2015, p. 273) This paper primarily take issue with the linear depiction of technological improvements in leading smartphone firms in Figure 1 because upgrading is a complicated process involving different strategies and forms of innovation. Instead, it argues that leading Chinese smartphone firms subscribe to a non-linear upgrading process. -

Susan M. Walcott.Pmd

Indian Journal of Economics & Business, Special Issue China & India (2006) : 1-... HIGH TECHNOLOGY CLUSTERS IN INDIA AND CHINA: DIVERGENT PATHS SUSAN M. WALCOTT Georgia State University, Atlanta and JAMES HEITZMAN University of California, Davis The economic giants of Asia, India and China, encourage clusters of high technology companies to fuel their national economic development drives, but the paths of these neighbors follow divergent trajectories due to different interconnections between government policy and business strategy. Based on field research, economic data and targeted case studies, this article explores the impact of regional political agency, technology infrastructure (unconnected versus integrated), the central government (hands-off versus highly involved), private capital (large versus negligible), and foreign direct investment. The picture emerging from each countrys profile allows assessment of short and long-term change for these urban clusters. 1. THE TECHNOPOLE AND ASIAN URBANIZATION A growing body of multi-disciplinary scholarship focuses on technopoles: dynamic clusters of research and production organizations generating rapid employment growth within innovative sectors, forming an important component of public policy. The technopole effect - encompassing spin-offs from co-located science or business parks, the segregated enclaves of privileged employees, attractive recreational amenities, and enabling infrastructure - produces a characteristic urban morphology within an emerging category of technology-based world cities. The transformed environments where the technopole effect occurs, often defined as corridors, signify a major component in urban policy that aims at the stimulation of services on the borders of former urban cores. A clear need exists for examining such spaces of human interaction, based on case studies of new urban developments offering possibilities for global application (Grant and Nijman 2002). -

EVOLVING MADE in CHINA 2025 Priority Adjustments and Implications for Europe’S Innovation Capacity

MERICS PAPERS ON CHINA Preview EVOLVING MADE IN CHINA 2025 Priority adjustments and implications for Europe’s innovation capacity Max J. Zenglein | Anna Holzmann Evolving Made in China 2025 Evolving Made in China 2025: Priority adjustments and implications for Europe’s innovation capacity by Max J. Zenglein and Anna Holzmann KEY POINTS In the first three years after its release, industrial policy scheme aimed at propel- China’s industrial masterplan Made in China ling China towards global tech leadership. 2025 has been repeatedly adapted to fit Chinese authorities have identified en- a changing internal and external environ- gagement with emerging industries as ment. great opportunities to get ahead of ad- Against the backdrop of an escalating vanced economies. trade conflict with the United States and Europe’s innovation landscape is already growing pushback against ambitious in- subject to Chinese pressure stemming dustrial policies, China has toned down its from its advances to spearhead future assertive rhetoric. In practice, the roll-out technologies such as batteries for electric of Made in China 2025 is in full swing. vehicles (EVs) and Artificial Intelligence The strategy is part of a sophisticated (AI). Made in China A lot has happened since the release of the Made in China 2025 strategy in 2015. The plan de- 2025 promotes fines ten core industries that China wants to upgrade to compete on a global scale. These include greater new-generation information technology, high-end computerized machines and robots, aviation independence and space equipment, energy-saving and new energy vehicles, and new materials. However, over the course of the past three years, it has become evident that the ambitions and impact of the and, ultimately, industrial policy go far beyond these core industries. -

Memory Lane and a Look Down the Road: China Progressing in NAND but Hurdles Remain

21 July 2019 | 12:06PM EDT Made in the USA or China Memory lane and a look down the road: China progressing in NAND but hurdles remain Mark Delaney, CFA +1(212)357-0535 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Allen Chang +852-2978-2930 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. We believe that China’s efforts to enter the global DRAM and NAND markets merit a Daiki Takayama +81(3)6437-9870 | deeper dive into how the memory industries have evolved over time, what impact [email protected] Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. China’s entry into other commodity tech industries (such as LEDs and solar) has had Toshiya Hari on fundamentals, where we believe the leading China-based memory companies +1(646)446-1759 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC stand at present with their efforts to enter the market (and the challenges that still Satoru Ogawa +81(3)6437-4061 | exist for entering the market — with GlobalFoundries as an example that [email protected] leading-edge semi production is difficult even for well-funded efforts), and what we Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. Alexander Duval believe all this means for the stocks of the established memory, drive, and semi +44(20)7552-2995 | [email protected] equipment companies. Goldman Sachs International Timothy Sweetnam, CFA With over $150 bn of semiconductors shipped to China in 2018, per the +1(212)357-7956 | [email protected] Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), and China domestic semi firms having Goldman Sachs & Co. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

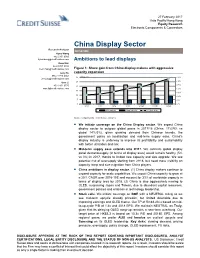

China Display Sector

27 February 2017 Asia Pacific/Hong Kong Equity Research Electronic Components & Connectors China Display Sector Research Analysts INITIATION Kyna Wong 852 2101 6950 [email protected] Ambitions to lead displays Keon Han 82 2 3707 3740 [email protected] Figure 1: Share gain from China display makers with aggressive Jerry Su capacity expansion 886 2 2715 6361 30 (M sq. m) 35% [email protected] 30% Sam Li 25 25% 852 2101 6775 20 [email protected] 20% 15 15% 10 10% 5 5% 0 0% 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016E 2017E 2018E WW capacity China capacity % China share Source: Company data, Credit Suisse estimates ■ We initiate coverage on the China Display sector. We expect China display sector to outgrow global peers in 2017/18 (China: 17%/9% vs global 14%/3%), given growing demand from Chinese brands, the government policy on localisation and mid-term supply ease. China's display industry is underway to improve its profitability and sustainability with better utilisation and mix. ■ Mid-term supply ease extends into 2H17. We estimate global display panel demand-supply (in terms of display area) would remain healthy (5% vs 3%) in 2017, thanks to limited new capacity and size upgrade. We see potential risk of oversupply starting from 2H18, but need more visibility on capacity ramp and size migration from China players. ■ China ambitions in display sector. (1) China display makers continue to expand capacity for scale capabilities. We expect China capacity to grow at a 25% CAGR over 2016-18E and account for 33% of worldwide capacity in terms of display area by 2018.