The Constitutionality of Free Education in Namibia: a Statutory Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Namibia's Child Welfare Regime, 1990-2017

CENTRE FOR SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH Namibia’s Child Welfare Regime, 1990-2017 Isaac Chinyoka CSSR Working Paper No. 431 February 2019 Published by the Centre for Social Science Research University of Cape Town 2019 http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za This Working Paper can be downloaded from: http://cssr.uct.ac.za/pub/wp/431 ISBN: 978-1-77011-418-0 © Centre for Social Science Research, UCT, 2019 About the author: Dr Isaac Chinyoka completed his PhD at the University of Cape Town in 2018. His PhD, supervised by Jeremy Seekings, examined child welfare regimes in four Southern African countries: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe. His PhD research was funded primarily by UKAid through the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council, grant ES/J018058/1 to Jeremy Seekings, for the “Legislating and Implementing Welfare Policy Reforms” research project. Namibia’s Child Welfare Regime, 1990-2017 Abstract Most countries in Southern Africa are similar in providing some form of cash transfers to families with children, primarily to reduce child poverty, but there are striking variations in the categories of children targeted and the reach of social grants. Namibia adopted South Africa-like child grants during South Africa rule. Namibia’s child welfare regime, like most other regimes in Southern Africa, started with and maintained a strongly familial child welfare regime (CWR), focused on children living in families with only one or no parents present. Whereas South Africa, after its transition to democracy, introduced a Child Support Grant (CSG) - that expanded massively the reach of child grants - Namibia did not do likewise. -

Namibia:Unfinished Business Within the Ruling Part

Focus on Namibia Namibia: Unfinished business within the ruling party There is a new president at the helm, but the jostling for position within the ruling Swapo party, which started in 2004, has not ended. Would the adversaries’ long-held dream that the strongest and most viable opposition in Namibia emerges from within the ranks of Swapo itself, come true? Axaro Gurirab reports from Windhoek. “Can you believe it: the sun is still significant and gallant contribution to the These questions are relevant because rising in the East and setting in the West!” So democratisation of Africa. during the week leading up to the May 2004 exclaimed a colleague of mine on the occasion The political transition had seen a heated extraordinary congress, Nujoma fired of the inauguration of President Hifikepunye contest between three Swapo heavyweights, Hamutenya as foreign minister, as well as the Pohamba on 21 March 2005. This simple namely Swapo vice-president Hifikepunye then deputy foreign minister, Kaire Mbuende. observation was quite profound because until Pohamba, current prime minister Nahas Angula, It was thought at the time that Nujoma, who then many people had been at their wits’ end and former foreign affairs minister Hidipo was personally campaigning for Pohamba, took trying to imagine Namibia without Sam Nujoma, Hamutenya. these drastic steps in order to send a strong the president of the ruling Swapo party. At the extraordinary party congress in May message to the congress delegates about who He had been the country’s first president, 2004, Angula fell out in the first round, and he liked and did not like. -

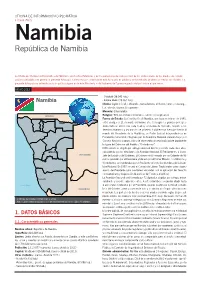

Namibia República De Namibia

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Namibia República de Namibia La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios no oficiales. La presente ficha país no defiende posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. MARZO 2018 - Oshakati (36.541 hab.) Namibia - Katima Mulilo (28.362 hab.) Idioma: inglés (oficial), oshivambo, nama-damara, afrikaans, herero, rukavango, lozi, alemán, tswana, bosquimano Moneda: dólar namibio ANGOLA Religión: 90% de cristianos (luteranos, católicos y anglicanos) Forma de Estado: La Constitución de Namibia, aprobada en febrero de 1990, en- Ruacana Rundu tró en vigor el 21 de marzo del mismo año. Consagra los grandes principios demo- cráticos: elecciones cada 5 años, economía de mercado, respeto a los derechos Tsumeb humanos y separación de poderes. Establece un Ejecutivo fuerte al mando del Presidente de la República, un Poder Judicial independiente y un Parlamento bi- cameral, integrado por la Asamblea Nacional (cámara baja) y el Consejo Nacional (cámara alta y de representación regional). Existe igualmente la figura del Defen- sor del Pueblo u “Ombudsman”. El Presidente es elegido por sufragio universal directo y secreto cada cinco años, Gobabis Windhoek coincidiendo con las elecciones a la Asamblea Nacional. El Presidente es, a la vez, Swakopmund BOTSUANA Jefe del Estado y del Gobierno. El Gobierno está formado por un Gabinete de Mi- nistros presidido por el Presidente y liderado por el Primer Ministro. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$45.00 WINDHOEK - 6 November 2019 No. 7041 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICES No. 330 Notification of polling stations: General election for the President and members of the National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 .............................................................................................................. 1 No. 331 Notification of registered political parties and list of candidates for registered political parties: General election for election of members of national Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ....................................... 33 ________________ Government Notices ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF NAMIBIA No. 330 2019 NOTIFICATION OF POLLING STATIONS: GENERAL ELECTION FOR THE PRESIDENT AND MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: ELECTORAL ACT, 2014 In terms of subsection (4) of section 89 of the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act No. 5 of 2014), I make known that for the purpose of the general election of the President and members of the National Assembly - (a) polling stations have been established under subsection (1) of that section in every constituency of each region at the places mentioned in Schedule 1; (b) the number of mobile polling stations in each constituency is indicated in brackets next to the name of the constituency of a particular region and the location of such mobile polling stations will be made known by the returning officer, in terms of subsection (7) of that section, in a manner he or she thinks fit and practical; and (c) polling stations have been established under subsection (3) of that section at the Namibian diplomatic missions and at other convenient places determined by the Electoral Commission of Namibia, after consultation with the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, at the places mentioned in Schedule 2. -

Advocacy in Action: a Guide to Influencing Decision-Making In

ADVOCACY IN ACTION A guide to influencing decision-making in Namibia Gender Research and Advocacy Project LEGAL ASSISTANCE CENTRE Windhoek 2004 Updated 2007 This publication was developed with assistance and support from the following organisations: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This publication, was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS his publication was prepared by the Legal Assistance Centre with support from the Tfollowing organisations: Austrian Development Cooperation, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This manual was written by Dianne Hubbard and Delia Ramsbotham of the Legal Assistance Centre, and illustrated by Nicky Marais. The following persons provided research for the manual: Dianne Hubbard, Legal Assistance Centre Delia Ramsbotham, Legal Assistance Centre, intern through the Young Professionals International Internship Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade of Canada, coordinated through the Canadian Bar Association Maria-Laure Knapp, Legal Assistance Centre, intern in a program of Youth International Internship Programme (YIIP) of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) of Canada, coordinated through Acadia University in Canada Evelyn Zimba, Legal Assistance Centre Anne Rimmer, a Development Worker funded by International Cooperation for Development (ICD) through the Catholic Institute for International Relations (CIIR). -

Michael Fergus Peter Manning Harald Eide

1 Michael Fergus Peter Manning Harald Eide 2 LIST OF PRINCIPAL ACRONYMS BCLME Benguela Current Large Marine Eco-System BENEFIT Benguela Environment Fisheries Interaction and Training Programme DMA Directorate of Maritime Affairs EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone FIOC Fisheries Inspectors’ and Observers’ Courses GMDSS Global Maritime Distress and Safety System IBCC Interim Benguela Current Commission ILO International Labour Organisation IMO International Maritime Organisation IMR Institute for Marine Research, Bergen INFOPECHE Intergovernmental Organisation for Marketing Information and Cooperation service for Fish and Fisheries Products in Africa INFOSA Marketing and Technical Advisory Service for the Fisheries Industry in Southern Africa ITCW International IUU Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fisheries LMTS Lüderitz Maritime Training School MCS Monitoring Control and Surveillance MFMR Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources NAMFI Namibian Maritime and Fisheries Institute NATMIRC National Marine Information and Research Centre NCFS Norwegian College of Fisheries Science, Tromsø NFDS Nordenfjeldske Development Services NMD Norwegian Maritime Directorate SADC Southern African Development Community SEAFO South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation STCW International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watch-keeping for Seafarers SWAPO South-West African People´s Organisation TAC Total Allowable Catch UNAM University of Namibia UNDP United Nations Development Programme 3 Table of Contents Page No. Paragraph Nos. Foreword -

Democracy Report Issue No

DEMOCRACY REPORT Issue No. 5 2011 A Civil Society Perspective On Parliament STILL NOT SPEAKING OUT An assessment of MPs’ performance indicates that quite a number do not make full use of their seats in Parliament for the benefit of society, rather choosing to be silent and anonymous, which raises questions as to their fitness to be in the legislature t has long been a criticism of Parliament and individ- released an assessment report of the performance of MPs participated in ordinary debate. The aggregate ual politicians occupying seats there that they have MPs over a two-year period – September 2005 to Octo- number of lines from speeches, questions, replies and Ibecome inactive, ineffectual and even removed from ber 2007 – which indicated that during that time a num- contributions to motion debates determines the ranking the general populace. ber of MPs had hardly uttered a word in the National of an individual MP. As evidence, critics have pointed to the number of Assembly. Topping the list of best performers – when consider- bills tabled and laws passed, and even the quality of The title of the IPPR report – ‘Not speaking out’ – ing the number of lines in Hansard for the three-month debates, in any parliamentary cycle to illustrate that the appropriately captured the worrying fact that quite a period from February to April 2011 – is Swapo Party MP Namibian Parliament has fallen into some sort of legis- number of MPs could not be bothered to take part in the and Minister of Environment and Tourism, Netumbo lative slumber. important debates which shape the legislative frame- Nandi-Ndaitwah. -

Namibia República De Namibia

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Namibia República de Namibia La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comuni- cación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios no oficiales. La presente ficha país no defiende posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. MAYO 2013 - Oshakati (36.541 hab.) Namibia - Katima Mulilo (28.362 hab.) Idioma: inglés (oficial), oshivambo, nama-damara, afrikaans, herero, rukavango, lozi, alemán, tswana, bosquimano Moneda: dólar namibio ANGOLA Religión: 90% de cristianos (luteranos, católicos y anglicanos) Forma de Estado: La Constitución de Namibia, aprobada en febrero de 1990, Rundu entró en vigor el 21 de marzo del mismo año. Consagra los grandes principios democráticos: elecciones cada 5 años, economía de mercado, respeto a los derechos humanos y separación de poderes. Establece un Ejecutivo fuerte al mando del Presidente de la República, un Poder Judicial independiente y un Parlamento bicameral, integrado por la Asamblea Nacional (cámara baja) y el Consejo Nacional (cámara alta y de representación regional). Existe igualmente la figura del Defensor del Pueblo u “Ombudsman”. El Presidente es elegido por sufragio universal directo y secreto cada cinco años, Windhoek coincidiendo con las elecciones a la Asamblea Nacional. El Presidente es, a la vez, BOTSUANA Jefe del Estado y del Gobierno. El Gobierno está formado por un Gabinete de Mi- nistros presidido por el Presidente y liderado por el Primer Ministro. -

Independence 1990-2015

Independence 1990-2015 On 22 March, I may wake up at 12h00 Africa has produced strong, effective and world-class leaders • 25 young Namibians to take to lunch • What happened to our dreams? • A young man called Untag speaks out • Hits and misses of education • Born on Independence Day • The rise and fall of fishing • Gerhard Mans, an eagle’s eye on rugby • FW de Klerk: I admire Namibia INSIDE CREDITS Physical address: Industria Street - Erf 189 Printing of newspapers, Lafrenz (Ext 1) Windhoek Namibia inserts and special supplements 25th Namibian Independence New, reliable, proven 1990-2015 print (Goss) machines with advanced technology Competitive pricing EDITOR Tangeni Amupadhi WINDHOEK OFFICE Phone: 061 279 600; Fax: 061 279 602 MAGAZINE COMPILED BY Christof Maletsky Address: John Meinert Street Personal client and SUB EDITING Cindy van Wyk & Natasha Uys P.O. Box 20783, Windhoek troubleshooting advice COVER The Namibian OsHAKATI OFFICE Phone: 065 220 246; Fax: 065 224 521 Experienced Children from Moria Grace Shelter in Katutura management COVER IMAGE Address: Metropolitan Building, Corner of Main Road and sta team celebrating independence. Photograph by Tanja Bause and Robert Mugabe Avenue Opposite the Magistrate’s Court High quality LAYOUT Caroline de Meersseman P.O. Box 31, Oshakati production and Dudley Minnie Oswald Shivute’s contact details: Tanya Turipamwe Stroh 081 241 2661; e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Quick delivery Advertising in Oshakati: SALes Strategic Publications and Sales Departments 065 224 -

Putro SOEMPENO Agricultural Attaché Indonesian Mission to The

Putro SOEMPENO Delima H. DARMAWAN Agricultural Attaché Assistant to the Coordinating Indonesian Mission to the Minister for Economic and Financial European Communities Affairs and for Supervision of Brussels Development Jakarta Patuan Natigor SIAGIAN Agricultural Attaché Endang S. TOHARI Indonesian Embassy Official Washington, D.C. Department of Agriculture Jakarta Achmad Mudzakir FAGI Head of Agriculture Research and Gunawan SUMODININGRAT Development Agency Official Department of Agriculture National Development Planning Jakarta Agency Jakarta Soleh SOHADLUDDIN Rector Rudi WIBOWO Bogor Agriculture Institute Secretary Jakarta Agribusiness Agency Department of Agriculture Justika S. BAHARSJAH Jakarta Official Department of Agriculture Ombo SATJADIPRADJA Jakarta Official Department of Forestry Ida Bagus PUTERA Jakarta Secretary-General Indonesian Farmer Association Alim FAUZI Jakarta Official Logistical Affairs Agency Em HARYADI Jakarta Official Department of Agriculture Purnama KELIAT Jakarta Official Department of Agriculture Anwar WARDHANI Jakarta Head of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Bureau Ferial LUBIS National Development Planning Official Agency Office of the Minister of Jakarta State for Food Affairs Jakarta Ato SUPRAPTO Official Department of Agriculture Jakarta 67 Ibnu SAID Pirooz HOSSEINI Official Director-General Department of Foreign Affairs Department for International Jakarta Economic and Specialized Affairs Ministry of Foreign Affairs RUHYANA Teheran Official Department of Agriculture Jakarta ROSEMALAWATI Second Secretary -

Tribute for Dr Abraham Iyambo by His Excellency Dr Nujoma

TRIBUTE BY HIS EXCELLENCY COMRADE DR SAM NUJOMA FOUNDING PRESIDENT AND FATHER OF THE NAMIBIAN NATION ON THE OCCASION OF THE MEMORIAL SERVICE OF THE HONOURABLE MINISTER OF EDUCATION DR ABRAHAM IYAMBO-MP 08 FEBRUARY 2013 PARLIAMENT GARDENS 0 | Page Director of Ceremonies; Kuku Helena Penothina Gabriel Shimbulu, the Children and the Entire Bereaved Family; Your Excellency, Comrade Hifikepunye Pohamba, President of the Republic of Namibia and Madam Penexupifo Pohamba, First Lady; Right Honourable Prime Minister, Comrade Hage Geingob; Honourable Speaker of the National Assembly, Comrade Theo-Ben Gurirab and Madam Guriras; Honourable Chairperson of the National Council, Comrade Asser Kapere and Madam Kapere; Your Honour, the Chief Justice Peter Shivute and Madam Shivute; Honourable Ministers; Honourable Members of Parliament; Honourable Regional Governors; Your Worship, the Mayors; Your Excellencies, Members of the Diplomatic Corps; Members of the Media; Fellow mourners: We are gathered here today, to pay our last respects and homage to one of Namibia’s gallant sons, a Marine Scientist and Honourable Minister of Education, the Late Comrade Dr. Abraham Iyambo. At the same time, we are celebrating his outstanding contribution to the building of the Namibian Nation. It was indeed with profound shock and disbelief that I learnt of the untimely passing on of the Minister of Education, the Late Comrade Dr. Abraham Iyambo, on February 2nd, 2013. Comrade Dr. Abraham Iyambo was a patriotic, committed and revolutionary SWAPO Party cadre. His death is a big loss, not only to his family but also to the entire Namibian Nation. The void he leaves behind will be difficult to fill. -

Namibian Teachers' Understanding of Education for All Issues

Namibian teachers’ understanding of education for all issues Roderick Fulata Zimba, Pempelani Mufune, Gilbert Likando and Pamela February University of Namibia Abstract The purpose of this study was to find out Namibian teachers’ understanding of their work circumstances, goals of education for all (EFA) and quality of education. To obtain data on these issues, a structured questionnaire was administered to a proportional representative sample of 1611 primary and secondary school teachers from six regions. Some of the study’s main findings were that several sampled teachers taught under difficult circumstances in which their schools lacked classroom furniture, electricity, water, teaching and learning materials; had problems communicating with parents of their learners; had difficulties managing overcrowded classrooms; were given heavy administrative loads that prevented them from effectively undertaking their teaching duties and that they knew little about the existence of EFA goals. These and other findings are discussed in the paper and developed into insights for enhancing educational practice in Namibia and for identifying issues on which to base further research. Roderick Fulata Zimba is a full Professor of Educational Psychology and Research Methodology at the University of Namibia. With University teaching, research and administration experience of over 30 years, he has published widely in Early Childhood Development, Moral Development, Youth Development, Inclusive Education, Values Education, Education for All, HIV/AIDS prevention and Discipline in Schools. E-mail address: [email protected] Pempelani Mufune is a full Professor of Sociology at the University of Namibia. He specialises in the sociology of development. His research interests include youth, environment and rural development.