Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 09/15/2017 04:52:09 PM EDT TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

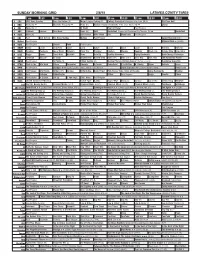

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Pioneer Las Vegas Bowl Sees Its Allotment of Public Tickets Gone Nearly a Month Earlier Than the Previous Record Set in 2006 to Mark a Third-Straight Sellout

LAS VEGAS BOWL 2016 MEDIA GUIDE A UNIQUE BLEND OF EXCITEMENT ian attraction at Bellagio. The world-famous Fountains of Bellagio will speak to your heart as opera, classical and whimsical musical selections are carefully choreo- graphed with the movements of more than 1,000 water- emitting devices. Next stop: Paris. Take an elevator ride to the observation deck atop the 50-story replica of the Eiffel Tower at Paris Las Vegas for a panoramic view of the Las Vegas Valley. For decades, Las Vegas has occupied a singular place in America’s cultural spectrum. Showgirls and neon lights are some of the most familiar emblems of Las Vegas’ culture, but they are only part of the story. In recent years, Las Vegas has secured its place on the cultural map. Visitors can immerse themselves in the cultural offerings that are unique to the destination, de- livering a well-rounded dose of art and culture. Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s colorful, public artwork Seven Magic Mountains is a two-year exhibition located in the desert outside of Las Vegas, which features seven towering dayglow totems comprised of painted, locally- sourced boulders. Each “mountain” is over 30 feet high to exhibit the presence of color and expression in the There are countless “excuses” for making a trip to Las feet, 2-story welcome center features indoor and out- Vegas, from the amazing entertainment, to the world- door observation decks, meetings and event space and desert of the Ivanpah Valley. class dining, shopping and golf, to the sizzling nightlife much more. Creating a city-wide art gallery, artists from around that only Vegas delivers. -

He's the Top Sports Marketer in 1000 Years

Syracuse University SURFACE David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Sport Management Dynamics 12-20-1999 He’s the Top Sports Marketer in 1,000 Years Rick Burton Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/sportmanagement Part of the Sports Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burton, R. (1999), “He’s the top sports marketer in 1,000 years,” Sports Business Journal, Vol. 2, No. 35, Dec. 20-26, 37. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sport Management by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He ’s the top sports marketer in 1,000 years - SportsBusiness Daily | SportsBusiness Journal Page 1 of 3 SBJ/December 20 - 26, 1999/No Topic Name He’s the top sports marketer in 1,000 years RICK BURTON Published December 20, 1999 With your permission, I'd like to borrow a Chicago maxim: "Vote early and vote often." In this case, I'd like to nominate and cast the first vote for David Stern, commissioner of the National Basketball Association, as sports marketer of the millennium. Yeah, I know that will bother some of you. There's no question that 1,000 years is a lot of territory to cover. Just picking from the last 99 years is daunting enough. To start, you'd have to pay tribute to Pete Rozelle, late commissioner of the National Football League and creator of NFL Properties. -

2012 Sports Media Marketing Awards International & National ‐ Finalists List

2012 SPORTS MEDIA MARKETING AWARDS INTERNATIONAL & NATIONAL ‐ FINALISTS LIST TELEVISION/VIDEO BEST SPOT* LONDON OLYMPICS 2012 BRITISH EUROSPORT IT'S NOT CRAZY, IT'S SPORTS. "SHAKE ON IT" ESPN, WIEDEN + KENNEDY NY NBA ON TNT REGULAR SEASON OPENING TEASE "FOREVER" TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU UFC ON FOX- "ORDINARY GUYS"- SWINGSET FOX SPORTS MARKETING SUPERSPORT TRANSFORMERS ORIJIN IT'S NOT CRAZY, IT'S SPORTS. "THE NAME" ESPN, WIEDEN + KENNEDY NY BEST TV/VIDEO CAMPAIGN 2011 ‐ 2012 NBA ON TNT REGULAR SEASON IMAGE CAMPAIGN TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU FRIDAY NIGHT HOCKEY SPORTSNET TSN ENTRY BELL MEDIA AGENCY TSN ENTRY #2 BELL MEDIA AGENCY NFL ON FOX "BETTER ON FOX" FOX SPORTS MARKETING OLYMPICS 2012 THACKWELL & WHITTAKER BEST USE OF DESIGN BBC1 BOAT RACE 2012 M‐I‐E PAGE 1 OF 8 NCAA MARCH MADNESS "BRACKETS EVERYWHERE" IMAGE TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU ESPN COLLEGE GAMEDAY OPEN TROIKA NBA ON TNT SHAQUILLE O'NEAL "GET READY" PROMO TURNER SPORTS – CSSU NFL ON FOX "LAUNCH" FOX SPORTS MARKETING OLYMPIA SRF BEST EDITING 2012 MLB REGULAR SEASON OPENING TEASE TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU HBO BOXING YEARENDER 2011 HBO NBC SPORTS: LEGACY NBC SPORTS AGENCY NCAA MARCH MADNESS "BRACKETS EVERYWHERE" IMAGE TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU SUPERSPORT TRANSFORMERS ORIJIN TOUR DE FRANCE CSQUARED PRODUCTIONS BEST DIRECTING* HOCKEY NIGHT IN CANADA LAUNCH SPOT CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION MLB EXTRA INNINGS 'SPECIAL DELIVERY' DIRECTV NBA ON TNT TALENT PROMOS ‐ SHAQ FREE THROW TURNER SPORTS – CSSU OLYMPIA SRF SUPERSPORT TRANSFORMERS ORIJIN PAGE 2 OF 8 NCAA MARCH MADNESS "BRACKETS EVERYWHERE" IMAGE TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU BEST USE OF AN ATHLETE* MLB EXTRA INNINGS 'SPECIAL DELIVERY' DIRECTV NBA ON TNT SHAQUILLE O'NEAL "GET READY" PROMO TURNER SPORTS ‐ CSSU NBC ‐ OLYMPIC COUNTDOWN LOWER 3RD MFACTOR INC. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sporting

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sporting Bodies, Displaying History: Black Embodiment and Performance in Contemporary Sports Films A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Samantha Noelle Sheppard 2014 © Copyright by Samantha Noelle Sheppard 2014 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Sporting Bodies, Displaying History: Black Embodiment and Performance in Contemporary Sports Films by Samantha Noelle Sheppard Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Kathleen McHugh, Co-Chair Professor Allyson Nadia Field, Co-Chair In this dissertation I analyze Black embodiment and performance in contemporary sports films, particularly through their documentary impulse, the gestures and markers through which these films establish their reference to real sporting and non-sporting bodies and histories. I argue that through this impulse, sports films make claims to an historical real, and they can therefore be explored for how they represent the Black sporting body. Though my project focuses primarily on fiction films, I begin by analyzing this impulse in a sports documentary for how it represents the performance and embodiment of the Black sporting body as an historical contestant. I then trace these strategies as they appear in and shape sports in fiction films, ii specifically through narratives of triumph and defeat, dissent, and gendered visibility. Throughout, I focus on and read the Black sporting body as a an individuated multiplicity which, through performance and embodiment, represents, references, and relates to Black sporting and non-sporting embodied histories and experiences. Sports films offer a privileged viewpoint on Black embodiment because of their high concentration of Black actors, one that mirrors representation in contemporary athletics. -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 8 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 8A | ATLANTIC NEWS | MAY 5, 2006 | VOL 31, NO 17 ATLANTICNEWS.COM . TOWN NEWS LOCAL NOTES DEMS ELECT OFFICERS, PLAN FORUM James House~ A proud past, a well-planned future NORTH HAMPTON | The North Hampton Democratic BY SKIP WEBB Report,” a landscape histori- the James House, its families The outlining of build- Committee recently held an organizational meeting to elect SPECIAL TO THE ATLANTIC NEWS cal study, a subsurface sur- and early social and eco- ings which were on the site new officers. HAMPTON | During its vey of the entire three-acre nomic influences affecting in the pat is being consid- Named to the slate were Pat Moreinis Dodge, president; first 11 years, the James site, and a genealogy of the the homestead and its inhab- ered. The clearing of two Judith Day, vice chairman; Peter Dodge, treasurer; Caroline House Association, Inc. con- James family were complet- itants. Some special pro- acres of woods, while sav- Field, secretary; and Robert O’Kane, delegate-at-large. centrated on the preserva- ed. Several archaeological grams were also provided. ing historical trees and The committee will sponsor the upcoming Congressional tion of the house, having the digs were performed, and Now in its 11th year, the plants which will help tell Candidates Forum on Sunday, May 7 at 6 p.m. -

Where to Buy Hockey Jerseys Cheap,Nba Hardwood Classics Jerseys

where to buy hockey jerseys cheap,nba hardwood classics jerseys 2015 NeQIUTHg--where to buy hockey jerseys cheap,nba hardwood classics jerseys 2015 NeQIUTHgwholesale nfl jerseys from china usa absolutely price to value--Rock bottom price with fine Quality. Shop wholesale cheap nfl jerseys from china with us, usa ,absolutely price to value. Navigation: Jump to explore content areas:,retro nba jerseys Network Bar & Login Section Navigation Main Blog Content Secondary Sidebar: Links for more information on Recent Stories,girls basketball jerseys, FanPosts and FanShots Masthead With the Thanksgiving holiday coming a multi function bit ahead of due date this year,nba practice jersey,within the next week are sometimes a multi functional short time week and we've since you have an opportunity and for all your family get among the great deals throughout the Caps tickets gorgeous honeymoons as well countless different match-ups. Want to explore start the holiday "revelry"ahead of due date Grab several of the tickets and for Wednesday good night as going to be the Caps take on Winnipeg at Verizon Center. The game average clean air amount of cash sits at $125,notre dame hockey jersey,a great deal more than $10 at less than going to be the Caps' a new one avg money of $136 and thanks for more information on TiqIQ's "Pick Your Price" feature all your family members can save for that matter a good deal more With an bring to the table of around $90 all over the a few of the"4-star" tickets (100-level behind goals of up to $168 retail value) all your family can save a lot more than $75 in line with oxygen,wholesale authentic nfl jerseys! Can't make Wednesday? Well get examples of the"Black Friday" deals enchanting Friday's big match-up to have going to be the Rangers. -

Mike Trainor's Roofing

GRAND REOPENING THIS WEEKEND AT CALL ANGEL PAINTING - THEIR WORK IS HEAVENLY VINCENZO’S LITTLE ITALY II • SEE PAGE 12 609-408-6874 • SEE PAGE 18 MIKE TRAINOR'S ROOFING We will beat ANY Legitimate Estimate Residential • Commercial Call Us: (609)884-1009 • 1-800-798-MIKE FREE Estimates • GAF Certified • Lifetime Warranty • 24 Hour Service [email protected] PAGE 2 JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE STEAK & SEAFOOD UNIQUE MARTINIS • FRESH SEAFOOD RESTAURANT TASTY STEAKS Happy Hour 4-6:30pm BAR OPEN FRIDAY, SATURDAY & SUNDAY Wednesday - Sunday SERVING FULL MENU Featuring our Bar Menu IN OUR DINING ROOM from 4pm FROM 5PM 615 LAFAYETTE ST, CAPE MAY • 609.884.2111 oysterbayrestaurant.com JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE PAGE 3 PAGE 4 JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE 40 MEDIA DRIVE HALLENGE QUEENSBURY, NEW YORK 12804 TV C 518-792-9914 hair 1-800-833-9581 A STYLING SALON SPRING IS IN6 THE09- 5 h22a-iHrA!I R ^(4 247) SPORTS STUMPERS Specia l Occas ion Hair Designs On640 1tour NEW with JERSE theY AV EPGANUE, WILDWOOD CREST By Georgewww.hairwildwoodcrest.com Dickie 9) Where is this year’s U.S. Open © Zap2it being played? 609-522-HAIR 10)(42 Is4 7this) a Presidents Cup year Questions: or a Ryder Cup year? 1) In what state is the first PGA Tour event of the new year Answers: played? 1) The Hyundai Tournament of 2) In what four states are PGA Champions is played in Kapalua, events generally concentrated in Hawaii January, February and March? 2) Arizona, California, Florida and 3) Three foreign countries are Hawaii represented on the 2015 sched- 3) Canada, South Korea and ule. -

Mkfpkfmr4212

Change Location,youth mlb jerseys This is Michael Russo's 17th year covering the National Hockey League. He's covered the Minnesota Wild for the Star Tribune since 2005 following 10 years of covering the Florida Panthers for the Sun-Sentinel. Michael uses ?¡ãRusso?¡¥s Rants?¡À to feed a wide-ranging hockey-centric discussion with readers,Bucks Jerseys,nike and nfl, and can be heard weekly on KFAN (100.3 FM) radio. George Richards Miami Herald sportswriter E-mail | Bio Chat with other sports fans in our message boards Ask us questions Greg Cote Dolphins Hurricanes High Schools Heat Marlins Panthers Wrestling Syndicate this site Powered by TypePad About On Frozen Pond Recent Posts OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Jason Garrison OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Erik Gudbranson Florida Panthers 2011-12 Wrap Up: Future Looks Bright OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Sean Bergenheim PACK 'EM UP: Florida Panthers Clear Out Lockers,vintage jersey, Head into Offseason OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Tomas Kopecky OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Stephen Weiss OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Brian Campbell OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Jose Theodore OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Ed Jovanovski Also find Russo on Facebook. His fight card at HockeyFights.com is long and distinguished,russian hockey jerseys, featuring bouts against players such as Tie Domi,cheap jersey, Stu Grimson,throwback nba jerseys, Tony Twist and Marty McSorley (below). Tha station’s master control in Houston cleared a path for tonight’s game to return to its somewhat new and improved format. -

NBA NEWS September 25, 2001 Volume 56, No. 1 Editor: Barry

NBA NEWS September 25, 2001 Volume 56, No. 1 Editor: Barry Rubinstein Assignment Editor: Jeanne Tang Contributing Writers: Mark Broussard, John Gardella, John Hareas, Rob Reheuser, Rita Sullivan For more information, log on to the NBA's official Web site at: http://www.nba.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Aiding the Relief Effort 2. Michael Jordan to Play for Wizards, Return to NBA 3. NBA Media Day Sites and Training Camp Information 4. Rules Changes to Take Effect 5. NBDL Announces First Player Allocations 6. NBDL Preseason Schedule Begins November 9 7. Field Set for 2002 Men's World Championship 8. Dunleavy, Elmore Headline NYC Hoop Hall Inductees 9. Mavericks Make Fashion Statement With New Uniforms 10. Transactions 11. NBA 2001-02 Key Dates 12. NBA on the Air 13. Upcoming NBA Birthdays 14. NBA Communications Group =================== 1. AIDING THE RELIEF EFFORT =================== The terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington D.C. on September 11 took thousands of lives and affected countless others. Since then the relief effort has been continual. For those who wish to make financial contributions, checks should be made payable to the Twin Towers Fund, PO Box 26999, New York, NY 10087-6999. Contributions can also be made to the Red Cross at www.redcross.org or by mail to American Red Cross Disaster Relief Fund, P.O. Box 3756, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10008. Several NBA teams are pitching in to the relief effort and many more are making plans to do so. -- The Atlanta Hawks, along with the Braves and Thrashers, each donated approximately $250,000 from the teams' management, staff and their charitable foundations. -

Brent Musburger

38TH ANNUAL CONGRATULATIONS CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME TO OUR On behalf of the Board of Trustees, the In addition to our esteemed honorees, tonight we honor Brent Executive Committee, the National Awards Musburger for his long, distinguished career in sports broadcasting. Committee and the nineteen chapters of Working for ABC/ESPN and also CBS for most of his almost fifty- The National Academy of Television Arts & years covering “live” sporting events, he seemed to be everywhere, Sciences, it is my pleasure to welcome you to whether it be basketball, golf, NBA, NASCAR, IRL races and the the 38th Annual Sports Emmy® Awards. FIFA World Cup. It is with great pleasure that we honor him this As the Chairman and a fan, the excitement evening with our Lifetime Achievement Award for Sports. generated over the last year by the coverage Tonight marks the 8th year of the Academy’s Jim McKay Sports CHUCK DAGES of the NBA Finals, the Summer Olympics, Memorial Scholarship program. This year, we are honoring Victor 12 Baseball World Series, College Football Championship and the Prieto of Christopher Columbus High School in Miami, Florida NFL Super Bowl, to name just a few of the sporting events covered with the McKay Scholarship for his outstanding work. The National by you in this room, is extraordinary. It is our honor this evening to Academy would like to extend its thanks to the networks for their S P ORTS celebrate the many individuals, organizations and companies that continued support of the Jim McKay Scholarship program. have contributed to these accomplishments and raised the level of Thank you and good luck to all of this evening’s nominees. -

Parsonsparsons

** PER 462 OFF PAID Over $ MONTH MSRP $57,735 MSRP 8,400 ECRWSS $ Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL * * * * – Search our inventory – Schedule service – Check out our collision center – Request a price quote Download our Free Mobile App to: Download our Free Mobile STK #3212 MSRP $37,160 STK #3212 MSRP 2014 Chevy Volt HD Crew Cab Z71 Navigation, Bose, Rear-Vision Camera Navigation, Bose, Rear-Vision LT Duramax Diesel, Convenience Package, LT 49,320 49,320 31,442 31,442 2015 Chevy Silverado 2500 $ $ $ STK #7099 $ Saturday, Saturday, ** Feb. 21, 2015 21, Feb. (715) 479-4421 (715) PER 236 OFF Over $ AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS MSRP $44,745 MSRP MONTH 8,000 $ * * * * ade-in. 5.3L V8 Engine 5.3L STK #8449 MSRP $18,470 STK #8449 MSRP Double Cab Z71 LT 2015 Chevy Sonic LT 36,683 16,602 36,683 16,602 2015 Chevy Silverado 1500 Backup Camera, Automatic, Power Windows & Locks Backup Camera, $ $ $ $ STK #5121 A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A ** ** PER PER 298 362 $ $ MONTH MONTH * * * * Sunroof STK #1387 MSRP $30,860 STK #1387 MSRP STK #5593 MSRP $25,530 STK #5593 MSRP Specially Driven: 3,300 miles 2014 Chevy Cruze LTZ 24,888 24,888 20,650 20,650 New 2014 Chevy Impala LT $ SHOPPING AROUND FOR A NEW CAR? A AROUND FOR SHOPPING $ SHOPPING AROUND FOR A NEW CAR? A AROUND FOR SHOPPING $ $ ** PER 306 $ OFF Over MONTH 7,000 $ of Eagle River NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL * * * * PRESIDENTS DAY SALE PRESIDENTS DAY PRESIDENTS DAY SALE PRESIDENTS DAY 5353 Hwy.