Encyclopedia of Title IX and Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0506Wbbmg011906.Pdf

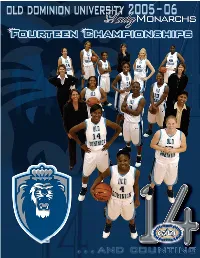

2005-06 OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY BasketballLADY MONARCH 1992 Fourteen-Time CAA Champions 1993 Table of Contents 1994 Media Information ................................................................................................... 2-3 Travel Plans .................................................................................................................. 4 The Staff 1995 Head Coach Wendy Larry ....................................................................................... 6-8 Assistant Coaches ................................................................................................... 9-12 Support Staff/Managers ...................................................................................... 13-14 1996 Meet the Lady Monarchs 2005-06 Outlook .................................................................................................... 16-17 Player Bios ............................................................................................................. 18-37 1997 Rosters .........................................................................................................................38 A Closer Look at Old Dominion This is Norfolk/Hampton Roads ....................................................................... 40-41 1998 Old Dominion University ................................................................................... 42-43 Administration/Academic Support .................................................................. 44-46 Athletic Facilities ...................................................................................................... -

Aau Karate Central District Championship

AAU KARATE CENTRAL DISTRICT CHAMPIONSHIP January 26, 2020 College of Lake County, Grayslake, Illinois 2020 AAU KARATE CENTRAL DISTRICT CHAMPIONSHIPS ATHLETE APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS 1. Athletes must be a current 2020 AAU member. If not, please apply for your AAU membership at www.aausports.org and provide a copy of your current membership with your application. 2. Complete the athlete application by entering the athlete’s information, years of karate experience, tournament categories, medical information, and sign the waiver/release form. 3. Acceptable forms of payment include: certified check, money order, or credit card. Please make certified check or money order payable to TKO. Personal checks will not be accepted. For credit card payments, please fill out the Credit Card Authorization Form attached and submit it via email or mail. Reference the Credit Card Authorization Form for more details. 4. New event divisions added: • Individualized Education Program (IEP) Division – open to all karate athletes competing in Kihon, Kata, and Kobudo with an IEP (Individualized Education Program for physical, emotional or developmental disabilities including, but not limited to, autism, down syndrome, cerebral palsy, paraplegic/wheel-chair, blind, deaf, etc.). • Beginner Kihon (Basics) Division – open to 5-7 year old beginners (less than one year experience). • Family Team Kata/Kobudo Division – open to all families consisting of three to four family members; each family member must have at least one of the following relationships with the oldest -

Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo Biblioteka • ------SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 the LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL

,-zo-uvos , Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo biblioteka • ----------------------------------- SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL. XCV 2010 DECEMBER - GRUODŽIO 7, NR.24. , DEVYNIASDEŠIMT PENKTIEJI METAI _____________________ LIETUVIŲ TAUTINĖS MINTIES LAIKRAŠTIS MĖNAIČIUOSE - LIETUVOS LAISVĖS KOVOS SĄJŪDŽIO MEMORIALAS Lapkričio 22 d. Miknių- vardai. džio Tarybos posėdyje priim Pėtrėčių sodyboje Mėnaičių Į bunkerio vidų patekti ta deklaracija, kurią pasirašė kaime, Radviliškio rajone, nebus galima, jį lankyto aštuoni posėdžio dalyviai. iškilmingai atidaryta Lietuvos jai galės apžiūrėti iš vir Nė vienas iš aštuonių šią laisvės kovos sąjūdžio šaus, įėję į atstatytą klėtį. istorinę deklaraciją pasira Tarybos 1949 m. vasario 16 Bunkerio viršus uždengtas šiusių signatarų neišdavė d. Nepriklausomybės deklara stiklu. Ekspozicijoje - restau juos saugojusių ir globoju cijos paskelbimo memorialas. ruoti partizanų daiktai, eks sių žmonių ir savo idealų. Memorialą, kurį sudaro ponatai iš Šiaulių „Aušros“ Deja, nė vienas legendinės atstatytas Lietuvos partizanų muziejaus ir Genocido aukų partizanų Deklaracijos si vyriausiosios vadavietės bun muziejaus fondų. gnataras laisvės nesulaukė. keris, virš jo esanti klėtis ir Istorija mena, kad Lietuva Nežinoma, kur ilsisi jų palai šalia bunkerio pastatytas pa ginklu priešintis sovietinei kai, todėl tikimasi, kad tin minklas, pašventino Lietuvos okupacijai pradėjo 1944 m. kamai sutvarkyta ši Lietuvai kariuomenės ordinaras vys ir ši kova tęsėsi iki 1953 m., svarbi istorinė vieta taps ne kupas Gintaras Grušas. kai buvo sunaikintos orga tik 1949 m. vasario 16-osios Memorialo atidarymo iš nizuotos Lietuvos partizanų deklaraciją pasirašiusių par kilmėse dalyvavo prezidentė pajėgos. tizanų atminimo ženklu, bet Dalia Grybauskaitė, kraš 1949 m. vasario 2-22 die ir amžinos pagarbos visų to apsaugos ministrė Rasa nomis Mėnaičių kaime buvo Lietuvos partizanų laisvės Juknevičienė, kariuomenės sušauktas visos Lietuvos siekiams simboliu. -

Extensions of Remarks E2251 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

November 19, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E2251 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS IN HONOR OF JANIS KING ARNOLD TRIBUTE TO MAJOR GENERAL Knight Order Crown of Italy; and decorations JOHN E. MURRAY from the Korean and Vietnamese Govern- ments. HON. DENNIS J. KUCINICH HON. BILL PASCRELL, JR. Madam Speaker, I was truly saddened by the death of General Murray. I would like to OF OHIO OF NEW JERSEY extend my deepest condolences to his family. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES My thoughts and prayers are with his daughter Wednesday, November 19, 2008 Valerie, of Norfolk Virgina, his granddaughter Wednesday, November 19, 2008 Shana and grandson Andrew of Norfolk Vir- Mr. PASCRELL. Madam Speaker, I rise ginia; his brother Danny of Arlington Virginia, Mr. KUCINICH. Madam Speaker, I rise today to honor the life and accomplishments and a large extended family. today in honor of Janis King Arnold, and in of veteran, civil servant, and author Major General John E. Murray (United States Army f recognition of 36 outstanding years of service Retired). HONORING REVEREND DR. J. in the Cleveland Metro School District. She Born in Clifton, New Jersey, November 22, ALFRED SMITH, SR. has been instrumental in bringing innovative 1918, General Murray was drafted into the educational programs to the Greater Cleve- United States Army in 1941 as a private leav- HON. BARBARA LEE land Area. ing his studies at St. John’s University and OF CALIFORNIA rose to the rank of Major General. The career Janis Arnold has a multifaceted and rich his- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES tory in public service and recently retired from that followed was to take him through three Wednesday, November 19, 2008 a long and illustrious career in the Cleveland wars, ten campaigns and logistic and transpor- tation operations throughout the world. -

Timoni Resign from School

ACLE CLARK, N J., VOL. 15 NO. 48 THURSDAY, AUGUST 25, 2005 www.focalsource.com TWO SECTJi Blaze Timoni resign destroys from school building By Vincent Gragnani and hopes to have someone sworn in By Vincent Gragnani Managing Editor at the board's Sept. 27 meeting. Managing Editor Citing health issues and other com- Lewis, sometimes at odds with Parts of Central Avenue, Terminal mitments, longtime school board Timoni, thanked him for his eight- Avenue and Raritan Road were closed member Michael Timoni resigned last and-a-half years of service. for several hours Saturday afternoon week, giving board members 60 days "He was committed to the Board of while firefighters extinguished a blaze from his Aug. 17 resignation to fill his Education and I personally commend in a building behind Chilis and Bartell space on the board. the work and effort he has exhibited. Farm and Garden Supply. Timoni delivered a brief letter of Timoni, a former president of the Clark Fire Chief John Pingor said resignation to interim Superintendent board, was serv- Monday that the cause of lie fire was Vito Gagliardi immediately after the ing as chairman still unknown. board's Aug. 16 meeting, a meeting at of the building Bartell leases the building — which Timoni was the lone vote and grounds com- mittee this year. which was completely destroyed but is against a reorganization of the board's still standing — to three businesses, central offices. The board will including a welding shop and a wood- Walking out at the end of that officially accept Photo By Vincent Gragnani working shop. -

Holt County Assessor

Mound City Published & Printed in Mound City, Missouri Vol. 133, No. 2 75¢ NEWS www.moundcitynews.com Thursday • July 19 • 201 2 Community Golden Triangle Energy blood drive appeals tax assessment to July 23 The last opportunity to give blood in Holt County Board of Equalization this month is on Monday July 23, in Mound City. Stockholders, employees From 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. at and the lawyer for Golden the McRae Community Triangle Energy (GTE) in Building at 1720 Nebras- Craig, MO, appeared be- ka Street, residents can fore members of the Holt give blood and be entered County Board of Equaliza- into a weekly drawing to tion (BOE) on Monday, July win a $50 gift card! 16, to appeal the county’s To make an appoint- 2012 $22 million property ment go to savealifenow. assessment. Present at the org and enter sponsor hearing were BOE mem- code: moundci tycomm1. bers Mark Sitherwood, By making an appoint- Bill Gordon, Don Holstine ment online, donors are and Barry Kreek (member instantly registered to Anna Lou Doebbling was Herb Derks, left- Of Gentry County, MO, laid down his win a grand prize give- absent). Also present were ‘golden shovel’ (shown on table) as he addressed the Board away! Donors may also Holt County Assessor Carla of Equalization (BOE) on Monday, July 16, regarding the value of Golden Triangle Energy to the county and what contact Elaine Bledsoe at Markt, Holt County Clerk 660-442-5235. he felt should be the board’s obligation to do whatever it Kathy Kunkel, and more could to keep industry in the county. -

Hampton Roads 2007 James V

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Economics Faculty Books Department of Economics 9-2007 The tS ate of the Region: Hampton Roads 2007 James V. Koch Old Dominion University, [email protected] Vinod Agarwal Old Dominion University, [email protected] John R. Broderick Old Dominion University, [email protected] Christopher B. Colburn Old Dominion University, [email protected] Vicky Curtis Old Dominion University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/economics_books Part of the Nonprofit Administration and Management Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Koch, James V.; Agarwal, Vinod; Broderick, John R.; Colburn, Christopher B.; Curtis, Vicky; Daniel, Steve; Hughes, Susan; Janik, Elizabeth; Lian, Feng; Lomax, Sharon; Manthey, Trish; Molinaro, Janet; Plum, Ken; Seaton, Maurice; Singh, Lowell; and Sun, Qian, "The tS ate of the Region: Hampton Roads 2007" (2007). Economics Faculty Books. 14. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/economics_books/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Economics at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors James V. Koch, Vinod Agarwal, John R. Broderick, Christopher B. Colburn, Vicky Curtis, Steve Daniel, Susan Hughes, Elizabeth Janik, Feng Lian, Sharon Lomax, Trish Manthey, Janet Molinaro, Ken Plum, Maurice Seaton, Lowell Singh, and Qian Sun This book is available at ODU Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/economics_books/14 251T-2007 State of the Region2:SOR MASTER 8/29/07 11:09 AM Page 1 CHESAPEAKE VIRGINIA BEACH HAMPTON THE STATE OF THE REGIONHAMPTON ROADS 2007 REGIONAL STUDIES INSTITUTE • OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY 251T-2007 State of the Region2:SOR MASTER 8/29/07 11:09 AM Page 3 September 2007 Dear Reader: his is Old Dominion University’s eighth annual State of the Region report. -

Career Records Season Records

Career Records Season Records Points Scored 3-PT. Field Goals Attempted Rebounding Average Games Played Points Scored 3-PT. Field Goals Attempted Rebounding Average Minutes Played 1. 2,187 . Phylesha Whaley, 1997-00 1. 729 . Erin Higgins, 2003-07 1. 15.3 . Courtney Paris, 2006-P 1. 140 . Caton Hill, 2000-2004 1. 788 . Courtney Paris, 2005-06 1. 244 . Carin Stites, 1990-91 1. 15.9 . Courtney Paris, 2006-07 1. 1,181 . LaNeishea caufield, 2001-02 2. 2,147 . Molly mcGuire, 1980-83 2. 537 . Etta maytubby, 1993-96 2. 9.5 . .Barbara Johnson, 1979 2. 133 . Stacey dales, 1998-02 2. 775 . Courtney Paris, 2006-07 2. 218 . Rosalind Ross, 2001-02 2. 15.03 . Courtney Paris, 2007-08 2. 1,179 . Erin Higgins, 2005-06 3. 2,141 . Courtney Paris, 2006-P 3. 414 . Chelsi Welch, 2003-07 3. 9.3 . Molly mcGuire, 1980-83 133 . Erin Higgins, 2003-07 3. 686 . Phylesha Whaley, 1999-00 3. 214 . Erin Higgins, 2005-06 3. 14.97 . Courtney Paris, 2005-06 3. 1,134 . Phylesha Whaley, 1999-00 4. 2,125 . LaNeishea caufield, 1999-02 4. 411 . .Carin Stites, 1991-92 4. 9.0 . .Shirley fisher, 1983-85 4. 132 . LaNeishea caufield, 1999-02 4. 626 . LaNeishea caufield, 2001-02 4. 202 . Jenna Plumley, 2007-08 4. 12.9 . Shirley fisher, 1983-84 4. 1,123 . Stacey dales, 2001-02 5. 1,920 . Stacey dales, 1998-02 5. 391 . Stacey dales, 1998-02 5. 8.8 . Terri adams, 1980 132 . Leah Rush, 2004-07 5. 611 . Stacey dales, 2001-02 5. -

North Carolina State University's Student Newspaper Since 1920

Weath‘ér Time to break out the electric blankets, muffs and long underwear 'cause it‘s 30mg to be a Techniciana bit on the nippy side tonight, baby! Today's highs shOuId be In the low 505, wuth tonight's lows North Carolina State University’s Student Newspaper Since 1920 plummeting to the 905 Volume LXVII. Number 40 Monday. December 2. 1985 Raleigh. North Carolina Phone 737-241 1/2412 Improvements cited for fee increases John Price have resources to meet." Haywood Dorsch said publications fees Staff Writer said. haven't increased since 1980 and that Housing costs will increase for he anticipated another fee increase Various university departments students in fraternity houses if an won't be needed for another four explained before the Student Fee increase proposed by the Fraternity years. Review Committee last week why Court Renters Board is approved. A representative from University they are requesting increased stu~ The board requested an increase of Dining said a $50 increase in the cost dent fees. $2.000 per house for next year. A of meal plans is necessary to pay for If approved by the university. the board member said the increase is salary increases and rising food proposed increases would increase necessary to repair many of the prices. tuition for the 198687 year by $21 houses. The official said the increases were and would increase the yearly cost of The board originally planned to unavoidable because salaries were a dorm room from $56 to 890. ask for a $4.000 increase but decided increased by the state Legislature depending on the residence hall. -

2003 NCAA Women's Basketball Records Book

AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 99 Award Winners All-American Selections ................................... 100 Annual Awards ............................................... 103 Division I First-Team All-Americans by Team..... 106 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans by Team ....................................................... 108 First-Team Academic All-Americans by Team.... 110 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners by Team ....................................................... 112 AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 100 100 ALL-AMERICAN SELECTIONS All-American Selections Annette Smith, Texas; Marilyn Stephens, Temple; Joyce Division II: Jennifer DiMaggio, Pace; Jackie Dolberry, Kodak Walker, LSU. Hampton; Cathy Gooden, Cal Poly Pomona; Jill Halapin, Division II: Carla Eades, Central Mo. St.; Francine Pitt.-Johnstown; Joy Jeter, New Haven; Mary Naughton, Note: First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Women’s Perry, Quinnipiac; Stacey Cunningham, Shippensburg; Stonehill; Julie Wells, Northern Ky.; Vanessa Wells, West Basketball Coaches Association. Claudia Schleyer, Abilene Christian; Lorena Legarde, Port- Tex. A&M; Shannon Williams, Valdosta St.; Tammy Wil- son, Central Mo. St. 1975 land; Janice Washington, Valdosta St.; Donna Burks, Carolyn Bush, Wayland Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Dayton; Beth Couture, Erskine; Candy Crosby, Northeast Division III: Jessica Beachy, Concordia-M’head; Catie Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Harris, Ill.; Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Okla. Cleary, Pine Manor; Lesa Dennis, Emmanuel (Mass.); Delta St.; Jan Irby, William Penn; Ann Meyers, UCLA; Division III: Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Kaye Cross, Kimm Lacken, Col. of New Jersey; Louise MacDonald, St. Brenda Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Debbie Oing, Indiana; Colby; Sallie Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Elizabethtown; John Fisher; Linda Mason, Rust; Patti McCrudden, New Sue Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. St.; Susan Yow, Elon. -

Of 80 Greenwood Garden Club

Tingle, Larry D.: Newspaper Obituary and Death Notice Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities (Minneapolis, MN) - July 17, 2011 Deceased Name: Tingle, Larry D. Tingle, Larry D. age 71, of Champlin, passed away on July 12, 2011. Retired longtime truck driver for US Holland. He was an avid fisherman and pheasant hunter. Preceded in death by his son, Todd; parents and 4 siblings. He will be deeply missed by his loving wife of 45years, Darlene; children, Deborah (Doug) Rutledge, Suzanne (Brian) Murray, Karen Emery, Tamara (Matt) Anderson, Melissa (John) O'Laughlin; grandchildren, Mark (Megan), Carrie (Ben), Rebecca (Travis), Christine (Blake), Jason (Emily), Brent (Mandy), Shane, Jenna, Nathan, Alexa; step- grandchildren, Megann and Dylan; 2 great-grandchildren, James and Alison; sister, Marvis Godber of South Dakota; many nieces, nephews, relatives and good friends. Memorial Service 11 am Saturday, July 23, 2011 at Champlin United Methodist Church, 921 Downs Road, Champlin (763-421-7047) with visitation at church 1 hour before service. www.cremationsocietyofmn.com 763-560-3100 photoEdition: METRO Page: 08B Copyright (c) 2011 Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities Freida Tingle Bonner: Newspaper Obituary and Death Notice Winona Times & Conservative, The (Winona, Carrolton, MS) - July 15, 2011 Deceased Name: Freida Tingle Bonner GREENWOOD - Freida Tingle Bonner passed away Monday, July 11, 2011, at University Medical Center in Jackson. Services were held at 3 p.m. Wednesday, July 13, 2011, at Wilson and Knight Funeral Chapel with burial in Odd Fellows Cemetery in Greenwood. Visitation was held from 1 until 3 p.m. prior to the service on Wednesday. -

The NCAA News

Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association March 18,1992, Volume 29 Number 12 Gender-equity task force to go on a fast track A proposed genderequity task force is contain nine to 12 individuals. expected to work on an accelerated timetable Diversity in order to meet the NCAA’s legislative “That would include people within the Title IX only part of gender equity deadline, according to NCAA Executive membership who represent divergent Director Richard D. Schultz. groups from excellent athletics administra- When the NCAA announced the results equity is a philosophical consideration “I want this committee to conclude its tors to strong women’s rights advocates,” of the gender-equity survey March 11, the while Title IX is strictly legal. Member work so that any required legislation can be Schultz said. “Also, I anticipate there will be question arose as to the distinction between institutions may meet compliance stand- considered at the 1993 Convention,” Schultz people from outside advocacy groups, pos- Title 1X compliance and gender equity. ards for Title IX, Schultz said, but they said. “That means by the middle of August.” sibly a Congressman. We need to be very “Gender equity is not Title IX, and Title may not have gender equity in their pro- The idea of the task force was announced careful to come up with the right group.” IX is not gender equity,” Executive Direc- grams. at a March 1 I news conference at which the The formation of the task force is on the tor Richard D. Schultz said at the news For example, Schultz cited a common results of the NCAA’s gender-equity survey March 25 agenda of the NCAA Administra- conference announcing the results of the misconception: that the primary thrust of were revealed.