Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Graham Weston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

BFI Press Release: Missing Believed Wiped Bumper Christmas Stocking

For Immediate Release: Tuesday 7 November 2017, London. The BFI’s Missing Believed Wiped returns to BFI Southbank this December to present British television rediscoveries, not seen by audiences for decades, since their original transmission dates. The exciting, bespoke line-up of TV gems feature some of our most-loved television celebrities and iconic characters including Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part: Sex Before Marriage, Cilla Black in her eponymous BBC show featuring Dudley Moore , Jimmy Edwards in Whack-O!, a rare interview with Peter Davison about playing Doctor Who and a significant screen debut from a young Pete Postlethwaite. Lost for 50 years and thought only to survive in part, Till Death Us Do: Sex Before Marriage, originally broadcast on 2 January, 1967 on BBC1, sees Warren Mitchell’s Alf Garnett rail against the permissive society, featuring guest star John Junkin alongside regular cast members Dandy Nichols, Anthony Booth and Una Stubbs. Although the existence of this missing episode from the 2nd series has been known for some years, previous attempts to screen the episode had been refused with the print in the hands of a private collector. Having recently changed hands, MBW is delighted that access has been granted for this special one off screening, for one of 1960s best known and controversial UK television characters. Following last year’s successful screening of a previously lost episode of Jimmy Edwards’s popular 1950s BBC school-themed comedy romp Whack-O!, this year’s MBW programme includes a 1959 episode entitled The Empty Cash Box. Written by Frank Muir and Dennis Norden and starring Jimmy Edwards as the cane-happy headmaster, this episode was originally broadcast on the BBC on 1st December 1959. -

August 2016 • Issue 4

The newspaper for BBC pensioners Getting ready for Rio Page 9 August 2016 • Issue 4 Award for first OB truck The new female foreign brought back State Pension correspondent to life Page 2 Page 4 Page 6 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES 02 PENSIONS & STATE BENEFITS The new State Pension: what the changes mean for you he new State Pension has been after the introduction of the new State introduced for people who reach Pension will have been ‘contracted-out’ of State Pension age on or after the additional State Pension at some time – Benefits in brief 6 April 2016. This applies to: something they may be unaware of. • The guarantee part of Pension Credit increased in April to £155.60 (single person) T• men born on or after 6 April 1951, and The old State Pension has two parts: and £237.55 (couples). Government figures show that every year millions of • women born on or after 6 April 1953. • basic State Pension pensioners miss out on as much as £3.7 billion in money benefits, with many If you were born before those dates you’ll • additional State Pension (sometimes also forgoing benefits designed to help with the increased cost of having an be able to claim your State Pension under called State Second Pension, S2P or SERPS). illness and disability. Charities like Age UK are encouraging pensioners to check the old system instead. Anyone who has been contracted-out if they are eligible for Pension Credit. Pension Credit works by topping up your You can check when you’ll reach either paid National Insurance at a lower household income to a guaranteed minimum level. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

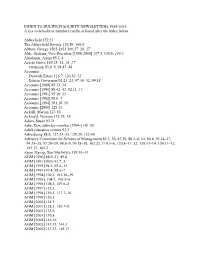

INDEX to DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 a Key to Newsletter Numbers Can Be at Found After the Index Below

INDEX TO DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 A key to newsletter numbers can be at found after the index below. Abbeyfield 152.31 The Abbeyfield Society 119.29, 160.8 Abbott, George 1562-1633 166.27–28, 27 Able, Graham, Vice-President [1998-2000] 117.9, 138.8, 140.3 Abrahams, Adam 85.3–4 Acacia Grove 169.25–31, 26–27 extension 93.8–9, 94.47–48 Accounts Dulwich Estate 116.7, 120.30–32 Estates Governors 92.21–23, 97.30–32, 99.18 Accounts [1989] 85.33–34 Accounts [1990] 88.42–43, 92.11–13 Accounts [1991] 95.10–13 Accounts [1992] 98.6–7 Accounts [1994] 101.18–19 Accounts [2000] 125.11 Ackrill, Marion 123.30 Ackroyd, Norman 132.19, 19 Adam, Susan 93.31 Adie, Don, sub-ctee member [1994-] 101.20 Adult education centres 93.5 Advertising 88.8, 127.33–35, 129.29, 132.40 Advisory Committee for Scheme of Management 85.3, 20, 87.26, 88.5–6, 12, 90.8, 92.14–17, 94.35–38, 97.29–39, 98.8–9, 99.18–20, 102.32, 114.5–6, 120.8–11, 32, 130.13–14, 134.11–12, 145.13, 165.3 Agent Zigzag, Ben MacIntyre 159.30–31 AGM [1990] 88.9–11, 89.6 AGM [1991] 90.9, 91.2, 5 AGM [1992] 94.5, 95.6–13 AGM [1993] 97.4, 98.6–7 AGM [1994] 100.5, 101.16–19 AGM [1995]. 104.3, 105.5–6 AGM [1996] 108.5, 109.6–8 AGM [1997] 112.5 AGM [1998] 116.5, 117.7–10 AGM [1999] 120.5 AGM [2000] 124.9 AGM [2001] 128.5, 130.7–8 AGM [2002] 132.6 AGM [2003] 136.8 AGM [2004] 140.16 AGM [2005] 143.33, 144.3 AGM [2006] 147.33, 148.17 AGM [2007] 152.2, 9 AGM [2008] 156.21 AGM [2009] 160.6 AGM [2010] 164.12 AGM [2011] 168.5 AGM [2012] 172.6 AGM [2013] 176.5 Air Training Corps Squadron 153.6–7 Aircraft -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Sep 11, 2011 06:00 IT IS WRITTEN HD WS PG On A Wing and a Prayer Religious programme. 06:30 IT'S IN THE AIR 1938 Repeat G It's In The Air Rejected by the air force, a man assumes the identity of his sister's fiance who is already in the Army. Starring: Jack Benny, Una Merkel 08:15 THE REBEL 1961 Repeat G The Rebel (AKA: Call Me Genius) Anthony Hancock gives up his office job to become an abstract artist. He has a lot of enthusiasm, but little talent, and critics scorn his work. Starring: George Sanders, Tony Hancock, Paul Massie, Margit Saad, Gregoire Aslan, Dennis Price 10:25 GOODBYE, MR CHIPS 1969 Repeat HD WS G Goodbye, Mr Chips Arthur Chipping a shy, withdrawn English school teacher falls in love with a flashy music hall star. Starring: Peter O'Toole, Petula Clark, Michael Redgrave, Alison Leggatt 13:30 THE GARDEN GURUS Repeat WS G The team give tips on feeding your plants to get best growth, introduce some new plant varieties and give tips on growing veggies just in time for spring. Plus, Trev gives a walk through Butchard Gardens telling the amazing story behind the gardens and its stunning colour plants. 14:00 GETAWAY Captioned Repeat WS PG Jules takes a journey back to Peru to see how a village has fared since a volunteer holiday he took 5 years ago. Dermotts off to Norway in search of the awesome King Crab; Kate Ceberano spends a night on the original Queen Mary ship which is said to be haunted, and we take a look at art holidays in the Barossa Valley and Sunshine Coast. -

See a Full List of the National Youth

Past Productions National Youth Theatre '50s 1956: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Worthington Hall, Manchester 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Moray House Theatre, Edinburgh 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith '60s 1960: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland. Theatre des Nations. Paris 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Ellen Terry Theatre. Tenterden. Devon 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ British entry at Berlin festival 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Italian Tour: Rome, Florence, Genoa, Turin, Perugia 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland and Belgium 1962: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells 1962: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells1962: 1962: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour for Centre 42. Nottingham, Leicester, Birmingham, Bristol, Hayes -

HP0192 Lindsay Anderson

1 The copyright of this interview is vested in the BECTU History Project. Lindsay Anderson, film director, theatre producer, interviewer Norman Swallow, recorded on 18 April, 1991 SIDE 1 Norman Swallow: First of all, when and where were you born? Lindsay Anderson: I was born on April 17th, 1923 in Bangalore, South India in the military hospital, I think. My father was in the British army in India, the Queen Victoria's Own, the Royal Engineers. My mother was half Scottish, her mother was Scottish and her father was English. She was born in South Africa and had met my father in Scotland . He was Scottish, and his family lived in Stonehaven, which is south of Aberdeen, and that is where they met and got married. Not altogether happily I don t think. There was a first son who died, a second son, my brother, who is living, who was an airline pilot and also flew in the War, and myself was born in India. And my parents divorced, do you know I can't even remember quite when, probably 10 or 11. I never knew my father terribly well, he served in India and most of time, I was brought up in England. I went to a respectable English preparatory school in West Worthing, St Ronan's, and I went to Cheltenham College. Not through any family connections, but my brother went to Cheltenham. And he went into the army, and then transferred into the airforce. I wasnt in the least military. I went up to Oxford for a year during the war and then went into the army. -

David Tucker Director

David Tucker Director David is a BAFTA and International Emmy-nominated director of film, television and theatre. He has directed over 40 professional theatre productions at the RSC (where he was an Assistant Director), the Bristol Old Vic, Liverpool Playhouse and Manchester Library theatres (at all of which he was Associate Director). David has also taught extensively at the NFTS, London Film Academy, Met Film School, Drama Centre London, Drama Studio London and has directed graduation productions at RADA, Drama Centre and Drama Studio London. Agents Christian Ogunbanjo [email protected] Credits Film Production Company Notes BURN THE CLOCK Raging Calm 25 minute short film. 2013 With Gemma Jones, Gawn Grainger. Television Production Company Notes EASTENDERS BBC TV Over 50 episodes Producers: Diederick Santer, Bryan Kirkwood, Dominic Treadwell-Collins, Sean O’Connor, John Yorke, Kate Oates, Jon Sen United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes HOLBY CITY BBC Series 15, 16 and 17, 21 10 x 60" Producers: Chris Clenshaw, Jane Wallbank CASUALTY BBC TV Series 28 and 29 4 x 50" LARK RISE TO BBC TV Series 2. episode 8 series 3, episode 2. CANDLEFORD Producer: Annie Tricklebank With Julia Sawalha, Mark Heap, Linda Bassett, Claudie Blakley DALZIEL AND PASCOE BBC TV 2 x 60’ minute film Producer: Annie Tricklebank With Warren Clarke, Michelle Dockery THE LAST DETECTIVE ITV 3 x 90’ minute films in Series 2,3,4 Producers: Deirdre