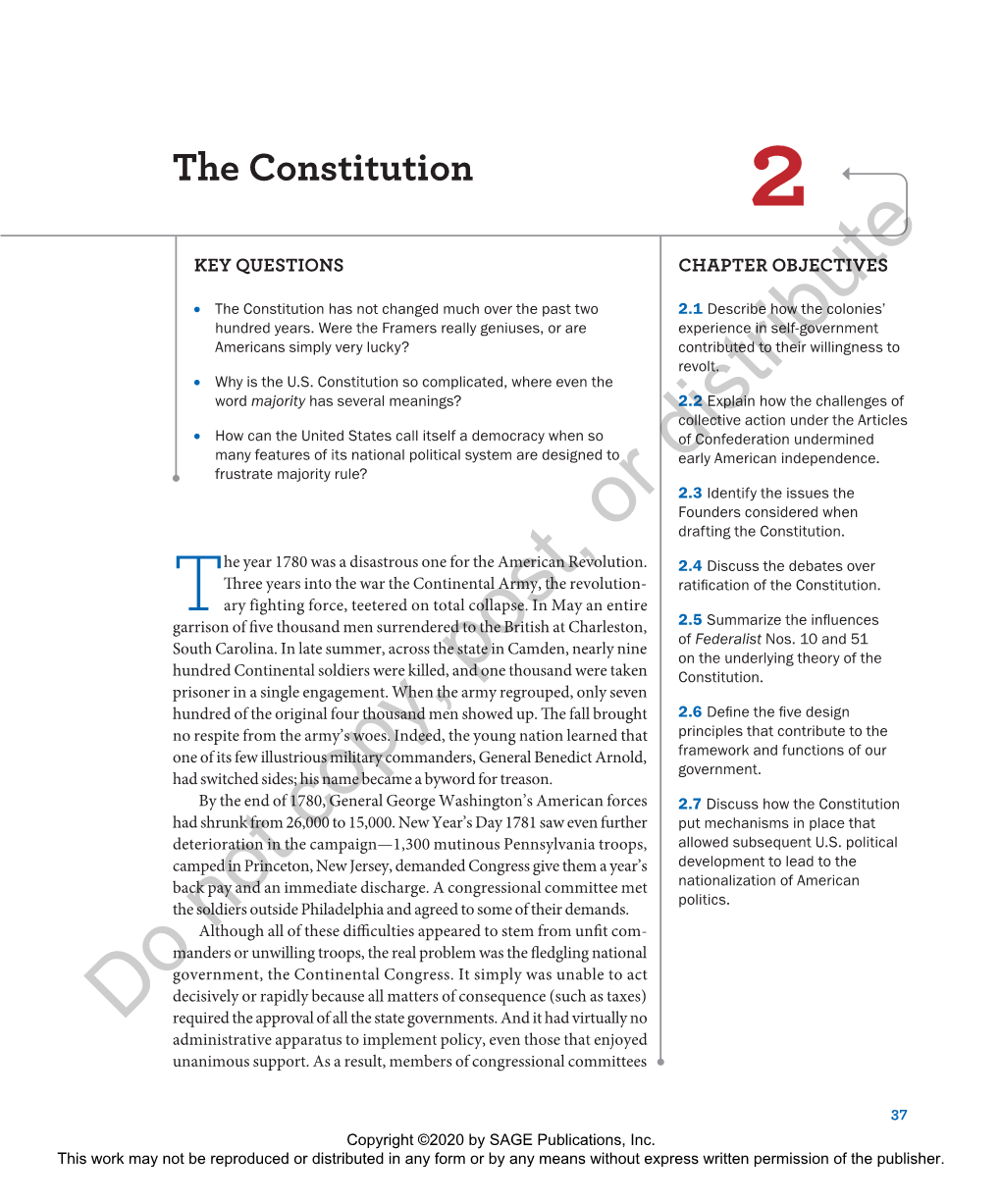

Chapter 2. the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 3 Article 5 March 2012 Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office Frederick B. Jonassen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Frederick B. Jonassen, Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 853 (2012), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss3/5 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj KISS THE BOOK . YOU’RE PRESIDENT . : “SO HELP ME GOD” AND KISSING THE BOOK IN THE PRESIDENTIAL OATH OF OFFICE Frederick B. Jonassen* INTRODUCTION .................................................854 I. THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE OF “SO HELP ME GOD” AS HISTORICAL PRECEDENT IN THE PRESIDENT’S INAUGURATION ...................859 A. Washington’s “So Help Me God” in the Supreme Court ..........861 B. Newdow v. Roberts.......................................864 II. THE CASE AGAINST “SO HELP ME GOD”..........................870 A. The Washington Irving Recollection ..........................872 B. The Freeman Source ......................................874 C. Two Conjectural Arguments for “So Help Me God” Discredited ...879 D. One More Conjecture .....................................881 III. THE EVIDENCE THAT WASHINGTON KISSED THE BIBLE ..............885 A. First-Hand Accounts of the Biblical Kiss ......................885 B. The Subsequent Tradition ..................................890 1. Andrew Johnson......................................892 2. Ulysses S. Grant......................................892 3. Rutherford B. Hayes...................................893 4. James A. -

Master Pages Test

Library & Archives Book Catalog Passaic County Historical Society Museum ~ Library ~ Archives Lambert Castle, 3 Valley Road, Paterson, New Jersey 07503-2932 Phone: (973) 247-0085 • Fax: (973) 881-9434 email: [email protected] www.lambertcastle.org May 2019 PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Library & Archives Book Catalog L.O.C. Call Number 100 Years of Collecting in America; The Story of Sotheby Parke Bernet N 5215 .N6 1984 Thomas E. Norton H.N. Abrams, 1984 108 Steps around Macclesfield: A Walker’s Guide DA 690 .M3 W4 1994 Andrew Wild Sigma Leisure, 1994 1637-1887. The Munson record. A Genealogical and Biographical Account of CS 71 .M755 1895 Vol. 1 Captain Thomas Munson (A Pioneer of Hartford and New Haven) and his Descendants Munson Association, 1895 1637-1887. The Munson record. A Genealogical and Biographical Account of CS 71 .M755 1895 Vol. 2 Captain Thomas Munson (A Pioneer of Hartford and New Haven) and his Descendants Munson Association, 1895 1736-1936 Historical Discourse Delivered at the Celebration of the Two-Hundredth BX 9531 .P7 K4 1936 Anniversary of the First Reformed Church of Pompton Plains, New Jersey Eugene H. Keator, 1936 1916 Photographic Souvenir of Hawthorne, New Jersey F144.H6 1916 S. Gordon Hunt, 1916 1923 Catalogue of Victor Records, Victor Talking Machine Company ML 156 .C572 1923 Museums Council of New Jersey, 1923 25 years of the Jazz Room at William Paterson University ML 3508 .T8 2002 Joann Krivin; William Paterson University of New Jersey William Paterson University, 2002 25th Anniversary of the City of Clifton Exempt Firemen’s Association TH 9449 .C8 B7 1936 1936 300th Anniversary of the Bergen Reformed Church – Old Bergen 1660-1960 BX 9531 .J56 B4 1960 Jersey City, NJ: Old Bergen Church of Jersey City, New Jersey Bergen Reformed Church, 1960 50th Anniversary, Hawthorne, New Jersey, 1898-1948 F 144. -

NAME of COLLECTION: DUER Family Papers DATES COVERED

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: DUER family Papers Gift of Denning Miller, 1981 SOURCE: Gift of Alice Duer Miller, 1937; gift of Jerry Granat, I986 Gift of Mary Benjamin, 1956 Purchase SUBJECT: The Duer family; William Alexander, Earl of Stirling, 1726-1783; William Duer, 17*17-1799; William Alexander Duer, 178O-I858. Social life and travels in Europe from 1832 to I89U. DATES COVERED: 178U - 1937 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 120 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols », boxes, or shelves) _ Bound: Boxed: 5 Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/Duer family RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: The Duer family papers, correspondence, diaries, genealogical manuscripts and notes, miscellaneous poetry, engravings, and early photographs, were assembled "by Caroline King Duer, 1865- 1956, Alice Duer Miller, 187^-19^2 (Barnard College A.B., 1899h and May King Van Rensselaer, 18U8-1925. Members of the Duer family include: William Alexander (Lord Stirling), 1726-1783, Revolutionary General; William Duer, 17^7-1799» Revolutionary Patriot; and William Alexander Duer, 1780-1858, Jurist and President of Columbia College from 1829 until 18U2. The letters of Anna Bridgen to Hannah Maria Denning Duer depict the social life of American expatriates in France and Italy during the l830fs. There are also diaries of Frances Maria Duer Hoyt's travels in Europe from 186U to I89U, and Hannah Maria Denning Duer's diaries from 1838 to 1862. For list of collection, see following page. HR - 3/8l D3(178)M Ms Coll Duer family -r Cataloged correspondence and manuscripts: Bridgen, Anna Box 1 Duer, Hannah Maria Denning (Mrs William Alexander), 1782-1862 Duer, William, 17^7-1799 Duer, William Alexander, I78O-I858 Hoyt, Frances Maria Duer (Mrs Henry Sheaff), 1809-1909 Box 2 King, James Gore, 1791-1853 Box 3 Miller, Alice Duer, 1$7^-19^2 Poor, Henry William, 18UU-1915 Swan, Jane P. -

Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: the Argument for a “New”

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 61 Issue 2 Article 4 2013 Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: The Argument for a “New” Interpretation of the Incompatibility Clause, the Removal & Disqualification Clause, and the Religious estT Clause—A Response to Professor Josh Chafetz’s Impeachment & Assassination Seth Barrett Tillman National University of Ireland Maynooth Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Constitutional Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Seth Barrett Tillman, Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: The Argument for a “New” Interpretation of the Incompatibility Clause, the Removal & Disqualification Clause, and the Religious estT Clause—A Response to Professor Josh Chafetz’s Impeachment & Assassination, 61 Clev. St. L. Rev. 285 (2013) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol61/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETING PRECISE CONSTITUTIONAL TEXT: THE ARGUMENT FOR A “NEW” INTERPRETATION OF THE INCOMPATIBILITY CLAUSE, THE REMOVAL & DISQUALIFICATION CLAUSE, AND THE RELIGIOUS TEST CLAUSE—A RESPONSE TO PROFESSOR JOSH CHAFETZ’S IMPEACHMENT & ASSASSINATION SETH BARRETT TILLMAN* I. THE METAPHOR IS THE MESSAGE ........................................ 286 A. Must Senate Conviction Upon Impeachment Effectuate Removal (Chafetz’s “Political Death”)? ...................................................................... 295 B. Is it Reasonable to Characterize Removal in Consequence of Conviction a “Political Death”? ...................................................... 298 C. Is Senate Disqualification a “Political Death Without Possibility of Resurrection”? .............. 302 II. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

The Life and Age of Woman | Stages of Woman's Life from Infancy to the Brink of the Grave

Item No. 1 [a bit of glare in photo] The Seven Stages of a Woman’s Life 1. Alden, Albert: THE LIFE AND AGE OF WOMAN | STAGES OF WOMAN'S LIFE FROM INFANCY TO THE BRINK OF THE GRAVE. [Barre, MA? c.1835-1840]. 18" x 21-1/2", visible printed area. Woodcut illustration, matted behind glass in attractive wood frame 27-1/2" x 30-1/4". Printed with black ink. Some wrinkling; loss to right blank upper corner. Else Very Good. A seven-figure image of seven stages of a woman's life: ages 1, 12, 18, 30, 50, 75, and 90. The figures stand upon pyramid steps; text printed beneath each illustration, all surrounded by a decorative border. A 30-year-old woman stands on the peak step,” at the zenith of her intellectual and physical powers." The 18-year-old, at "the most critical age in the life of a female," risks "bestowing [her affections] on man unworthily, or in vain" if she does not "first [give] her heart to God." The 50-year-old's "home is her castle" and her "time not spent in providing for her household is devoted to counseling her children, who at this time of her life are ready to go forth into society." The 90-year-old is a crone; "we see all that remains of her who at twelve and eighteen, tripped 'on th [sic] light fantastic toe.'" Alden's woodcut, "The Life and Age of Man," is well-known and based on the classical idea of the seven ages of man. -

Spring2020.Pdf

B A U M A N R A R E B O O K S Spring 2020 BaumanRareBooks.com 1-800-97-bauman (1-800-972-2862) or 212-751-0011 [email protected] New York 535 Madison Avenue (Between 54th & 55th Streets) New York, NY 10022 800-972-2862 or 212-751-0011 Monday - Saturday: 10am to 6pm Las Vegas Grand Canal Shoppes The Venetian | The Palazzo 3327 Las Vegas Blvd., South, Suite 2856 Las Vegas, NV 89109 888-982-2862 or 702-948-1617 Sunday - Thursday: 10am to 11pm Friday - Saturday: 10am to Midnight Philadelphia (by appointmEnt) 1608 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 215-546-6466 | (fax) 215-546-9064 Monday - Friday: 9am to 5pm all booKS aRE ShippEd on appRoval and aRE fully guaRantEEd. Any items may be returned within ten days for any reason (please notify us before returning). All reimbursements are limited to original purchase price. We accept all major credit cards. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Packages will be shipped by UPS or Federal Express unless another carrier is requested. Next-day or second-day air service is available upon request. www.baumanrarebooks.com twitter.com/baumanrarebooks facebook.com/baumanrarebooks On the cover: Item no. 4. On this page: Item no. 79. Table of Contents 16 4 42 100 113 75 A Representative Selection 3 English History, Travel & Thought 20 Literature 38 Children’s Literature, Art & Architecture 58 Science, Economics & Natural History 70 Judaica 81 The American xperienceE 86 93 Index 103 A A Representative Selection R e p r e s e n t a t i v e S e l e c t i o n 4 S “Incomparably The Most Important Work In p The English Language”: The Fourth Folio Of r Shakespeare, 1685, An Exceptionally Lovely Copy i 1. -

Founding Fathers on Screen: the Changing Relationship Between History and Film

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film Jennifer Lynn Garrott College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Garrott, Jennifer Lynn, "Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626696. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-42hs-e363 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film Jennifer Lynn Garrott Burke, Virginia Bachelor of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2010 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon.G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary August 2012 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lynn Garrott Approved by the Committee, August, 2012 Committee Chair Associate Professor Leisa Meyer, Lyon Gardir/br Tyler History Department, The College of W illiam ^ Mary __________ Associate Professor Andrew Figjfer, Lyon Gardiner Tyler History Department, The College of William & Mary Visiting Assistant Professor Sharon ZuberI jlish and Film Studies The College of William' lary ABSTRACT PAGE While historians have often addressed, and occasionally dismissed historical films, the relationship between history and film is ever changing. -

HIS 100: Introduction to Historical Methods: the World of Thomas Jefferson Fall 2010 Professor T. Slaughter Tuesday and Thursday

HIS 100: Introduction to Historical Methods: The World of Thomas Jefferson Fall 2010 Professor T. Slaughter Tuesday and Thursday RR Library 456, 9:40-10:55. Office hours: Tuesday and Thursday 11-noon, and by appointment. 369B RR; 273-2799 [email protected] Thomas Jefferson is an ideal focus for discussions of the range of subjects that fascinated him, from gardening to food, wine, women, education, politics, philosophy, architecture, and plantation management. He provides an exquisite example of Enlightenment culture during the age of revolutions, and of a Founding Father who, as Secretary of State, Vice President, and President attempted to implement the revolutionary and constitutional principles on which the United States was founded. His private correspondence and public papers, his published writings and private musings, give access to Jefferson’s inner landscape as well as the world in which he lived. Through films, non-fiction and fiction, and primary source documents relating to case studies—The Declaration of Independence and its contrast to Thomas Paine’s Common Sense; the Burr Conspiracy; and Jefferson’s relationship with his slave Sally Hemings—we will explore historical research and interpretation, both our own and that of other historians. In particular, we will look at some of the ways that historical research can go wrong, and how historical writing is always a reflection of perspectives rather than of gathered facts, of interpretations rather than recovery, of creativity rather than objective engagement with sources. Your grades will be based on attendance; active, knowledgeable participation in class discussions; and three papers that you will re-write after the first drafts are returned to you. -

The Beginning of the Constitutional Era: a Bicentennial Comparative Study of the American and French Constitutions

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1989 The Beginning of the Constitutional Era: A Bicentennial Comparative Study of the American and French Constitutions Rett R. Ludwikowski The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Rett R. Ludwikowski, The Beginning of the Constitutional Era: A Bicentennial Comparative Study of the American and French Constitutions, 11 MICH. J. INT’L L. 167 (1989). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEGINNING OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL ERA: A BICENTENNIAL COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE AMERICAN AND FRENCH CONSTITUTIONS Rett R. Ludwikowski* INTRODUCTION The expansion of constitutionalism is one of the most interesting phenomena of our time. Since World War II, a great number of states have either adopted new constitutions or changed their constitutional systems. The process of constitutional development was particularly intensified through the emergence of the socialist countries and the new states in Asia, Africa and the Near East.' The post-war constitutional experiences were, for the most part, dissatisfying. Without the extra-parliamentary means of constitu- tional control, the constitutions of the socialist countries operated more like political-philosophical declarations than legally binding norms. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 12

Ill I a* .^V/Jl'« **« c* 'VSfef' ^ A* ,VyVA° <k ^ °o ** ^•/ °v™v v-^'y v^-\*° .. http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog12newy .or ..V" *7yf^ a I*'. *b^ ^ *^^ oV^sua- ^ THE NEW YORK ical and Biographical Record. Devoted to the Interests of American Genealogy and Biography. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XII., 1881. PUBLISHED FOR THE SOCIETY, Mott Memorial Hall, No. 64 Madison Avenue, New Yopk. City. 4116 PUBLICATION "COMMITTEE. SAMUEL. S. PURPLE, JOHN J. LATTING, CHARLES B. MOORE, BEVERLEY R. BETTS. Mott Memorial Hall, 64 Madison Avenue. , INDEX TO SUBJFXTS. Abstracts of Brookhaven, L. I., Wills, by TosephP H Pettv a« ,«9 Adams, Rev. William, D.D., lk Memorial, by R ev ; E £' &2*>» •*"•*'>D D 3.S Genealogy, 9. Additions and Corrections to History of Descendants of Tames Alexander 17 Alexander, James and his Descendants, by Miss Elizabeth C. Tay n3 60 11 1 .c- ' 5 > Genealogy, Additions * ' ' 13 ; and Corrections to, 174. Bergen, Hon. Tennis G, Brief Memoir of Life and Writings of, by Samuel S. Purple, " Pedigree, by Samuel S. Purple, 152 Biography of Rev. William Adams, D.D., by Rev E ' P Rogers D D e of Elihu Burrit, 8 " 5 ' by William H. Lee, 101. ' " of Hon. Teunis G. Bergen, by Samuel S. Purple M D iao Brookhaven, L. I., Wills, Abstracts of/by Joseph H. Pe»y, 46, VoS^' Clinton Family, Introductory Sketch to History of, by Charles B. Moore, 195. Dutch Church Marriage Records, 37, 84, 124, 187. Geneal e n a io C°gswe 1 Fami 'y. H5; Middletown, Ct., Families, 200; pfi"ruynu vV family,Fa^7v ^49; %7Titus Pamily,! 100. -

Kenneth Hechler Papers, 1958-1976

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2010 0777: Kenneth Hechler Papers, 1958-1976 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the American Politics Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Political History Commons, and the Publishing Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth Hechler Papers, 1958-1976, Accession No. 2010/05.0777, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Inventory of the Kenneth Hechler Papers, 1958-1976 Accession 2010/05.0777 Scope and Content: Personal family papers, photographs and correspondence. Includes research material for Hechler's book, "The Bridge at Remagen". Also includes campaign material for Congressional races, West Virginia Secretary of State and a bid for the governorship of West Virginia. For additional materials created by Kenneth Hechler, look at the following collections: 2014/10.0820 2010/05.0702 1977/01.0199 Series I Family Series Ia Ancestry Box 1 (52 folders total) Folders 1-3 Ken’s genealogy research Folder 4 Notes on Gottfried Hechler Family