Construction of a General Measure Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernst Zermelo Heinz-Dieter Ebbinghaus in Cooperation with Volker Peckhaus Ernst Zermelo

Ernst Zermelo Heinz-Dieter Ebbinghaus In Cooperation with Volker Peckhaus Ernst Zermelo An Approach to His Life and Work With 42 Illustrations 123 Heinz-Dieter Ebbinghaus Mathematisches Institut Abteilung für Mathematische Logik Universität Freiburg Eckerstraße 1 79104 Freiburg, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Volker Peckhaus Kulturwissenschaftliche Fakultät Fach Philosophie Universität Paderborn War burger St raße 100 33098 Paderborn, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Library of Congress Control Number: 2007921876 Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A70, 03-03, 03E25, 03E30, 49-03, 76-03, 82-03, 91-03 ISBN 978-3-540-49551-2 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springer.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2007 The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant pro- tective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Typesetting by the author using a Springer TEX macro package Production: LE-TEX Jelonek, Schmidt & Vöckler GbR, Leipzig Cover design: WMXDesign GmbH, Heidelberg Printed on acid-free paper 46/3100/YL - 5 4 3 2 1 0 To the memory of Gertrud Zermelo (1902–2003) Preface Ernst Zermelo is best-known for the explicit statement of the axiom of choice and his axiomatization of set theory. -

Hausdorff Measure

Hausdorff Measure Jimmy Briggs and Tim Tyree December 3, 2016 1 1 Introduction In this report, we explore the the measurement of arbitrary subsets of the metric space (X; ρ); a topological space X along with its distance function ρ. We introduce Hausdorff Measure as a natural way of assigning sizes to these sets, especially those of smaller \dimension" than X: After an exploration of the salient properties of Hausdorff Measure, we proceed to a definition of Hausdorff dimension, a separate idea of size that allows us a more robust comparison between rough subsets of X. Many of the theorems in this report will be summarized in a proof sketch or shown by visual example. For a more rigorous treatment of the same material, we redirect the reader to Gerald B. Folland's Real Analysis: Modern techniques and their applications. Chapter 11 of the 1999 edition served as our primary reference. 2 Hausdorff Measure 2.1 Measuring low-dimensional subsets of X The need for Hausdorff Measure arises from the need to know the size of lower-dimensional subsets of a metric space. This idea is not as exotic as it may sound. In a high school Geometry course, we learn formulas for objects of various dimension embedded in R3: In Figure 1 we see the line segment, the circle, and the sphere, each with it's own idea of size. We call these length, area, and volume, respectively. Figure 1: low-dimensional subsets of R3: 2 4 3 2r πr 3 πr Note that while only volume measures something of the same dimension as the host space, R3; length, and area can still be of interest to us, especially 2 in applications. -

Caratheodory's Extension Theorem

Caratheodory’s extension theorem DBW August 3, 2016 These notes are meant as introductory notes on Caratheodory’s extension theorem. The presentation is not completely my own work; the presentation heavily relies on the pre- sentation of Noel Vaillant on http://www.probability.net/WEBcaratheodory.pdf. To make the line of arguments as clear as possible, the starting point is the notion of a ring on a topological space and not the notion of a semi-ring. 1 Elementary definitions and properties We fix a topological space Ω. The power set of Ω is denoted P(Ω) and consists of all subsets of Ω. Definition 1. A ring on on Ω is a subset R of P(Ω), such that (i) ∅ ∈ R (ii) A, B ∈ R ⇒ A ∪ B ∈ R (iii) A, B ∈ R ⇒ A \ B ∈ R Definition 2. A σ-algebra on Ω is a subset Σ of P(Ω) such that (i) ∅ ∈ Σ (ii) (An)n∈N ∈ Σ ⇒ ∪n An ∈ Σ (iii) A ∈ Σ ⇒ Ac ∈ Σ Since A∩B = A\(A\B) it follows that any ring on Ω is closed under finite intersections; c c hence any ring is also a semi-ring. Since ∩nAn = (∪nA ) it follows that any σ-algebra is closed under arbitrary intersections. And from A \ B = A ∩ Bc we deduce that any σ-algebra is also a ring. If (Ri)i∈I is a set of rings on Ω then it is clear that ∩I Ri is also a ring on Ω. Let S be any subset of P(Ω), then we call the intersection of all rings on Ω containing S the ring generated by S. -

Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory

Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth B.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2003 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Mathematics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2006 c 2008, David Worth iii DEDICATION To my lovely wife Meghan, to whom I am eternally grateful for her support and love. Without her I would never have followed my education or my bliss. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Terry Loring, for his years of encouragement and aid in pursuing mathematics. I would also like to thank Dr. Cristina Pereyra for her unfailing encouragement and her aid in completing this daunting task. I would like to thank Dr. Wojciech Kucharz for his guidance and encouragement for the entirety of my adult mathematical career. Moreover I would like to thank Dr. Jens Lorenz, Dr. Vladimir I Koltchinskii, Dr. James Ellison, and Dr. Alexandru Buium for their years of inspirational teaching and their influence in my life. v Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Mathematics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2006 Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth B.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2003 M.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2008 Abstract Geometric Measure Theory is the rigorous mathematical study of the field commonly known as Fractal Geometry. In this work we survey means of constructing families of measures, via the so-called \Carath´eodory construction", which isolate certain small- scale features of complicated sets in a metric space. -

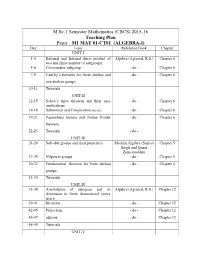

M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan

M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan Paper : M1 MAT 01-CT01 (ALGEBRA-I) Day Topic Reference Book Chapter UNIT-I 1-4 External and Internal direct product of Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 6 two and finite number of subgroups; 5-6 Commutator subgroup - do - Chapter 6 7-9 Cauchy’s theorem for finite abelian and - do - Chapter 6 non abelian groups. 10-11 Tutorials UNIT-II 12-15 Sylow’s three theorem and their easy - do - Chapter 6 applications 16-18 Subnormal and Composition series, - do - Chapter 6 19-21 Zassenhaus lemma and Jordan Holder - do - Chapter 6 theorem. 22-23 Tutorials - do - UNIT-III 24-26 Solvable groups and their properties Modern Algebra (Surjeet Chapter 5 Singh and Quazi Zameeruddin) 27-29 Nilpotent groups - do - Chapter 5 30-32 Fundamental theorem for finite abelian - do - Chapter 4 groups. 33-34 Tutorials UNIT-IV 35-38 Annihilators of subspace and its Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 12 dimension in finite dimensional vector space 39-41 Invariant, - do - Chapter 12 42-45 Projection, - do - Chapter 12 46-47 adjoins. - do - Chapter 12 48-49 Tutorials UNIT-V 50-54 Singular and nonsingular linear Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 12 transformation 55-58 quadratic forms and Diagonalization. - do - Chapter12 59-60 Tutorials - do - 61-65 Students Interaction & Difficulty solving - - M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan Paper : M1 MAT 02-CT02 (REAL ANALYSIS) Day Topic Reference Book Chapter UNIT-I 1-2 Length of an interval, outer measure of a Theory and Problems of Chapter 2 subset of R, Labesgue outer measure of a Real Variables: Murray subset of R R. -

Section 17.5. the Carathéodry-Hahn Theorem: the Extension of A

17.5. The Carath´eodory-Hahn Theorem 1 Section 17.5. The Carath´eodry-Hahn Theorem: The Extension of a Premeasure to a Measure Note. We have µ defined on S and use µ to define µ∗ on X. We then restrict µ∗ to a subset of X on which µ∗ is a measure (denoted µ). Unlike with Lebesgue measure where the elements of S are measurable sets themselves (and S is the set of open intervals), we may not have µ defined on S. In this section, we look for conditions on µ : S → [0, ∞] which imply the measurability of the elements of S. Under these conditions, µ is then an extension of µ from S to M (the σ-algebra of measurable sets). ∞ Definition. A set function µ : S → [0, ∞] is finitely additive if whenever {Ek}k=1 ∞ is a finite disjoint collection of sets in S and ∪k=1Ek ∈ S, we have n n µ · Ek = µ(Ek). k=1 ! k=1 [ X Note. We have previously defined finitely monotone for set functions and Propo- sition 17.6 gives finite additivity for an outer measure on M, but this is the first time we have discussed a finitely additive set function. Proposition 17.11. Let S be a collection of subsets of X and µ : S → [0, ∞] a set function. In order that the Carath´eodory measure µ induced by µ be an extension of µ (that is, µ = µ on S) it is necessary that µ be both finitely additive and countably monotone and, if ∅ ∈ S, then µ(∅) = 0. -

Chapter 2 Measure Spaces

Chapter 2 Measure spaces 2.1 Sets and σ-algebras 2.1.1 Definitions Let X be a (non-empty) set; at this stage it is only a set, i.e., not yet endowed with any additional structure. Our eventual goal is to define a measure on subsets of X. As we have seen, we may have to restrict the subsets to which a measure is assigned. There are, however, certain requirements that the collection of sets to which a measure is assigned—measurable sets (;&$*$/ ;&7&"8)—should satisfy. If two sets are measurable, we would like their union, intersection and comple- ments to be measurable as well. This leads to the following definition: Definition 2.1 Let X be a non-empty set. A (boolean) algebra of subsets (%9"#-! ;&7&"8 -:) of X, is a non-empty collection of subsets of X, closed under finite unions (*5&2 $&(*!) and complementation. A (boolean) σ-algebra (%9"#-! %/#*2) ⌃ of subsets of X is a non-empty collection of subsets of X, closed under countable unions (%**1/ 0" $&(*!) and complementation. Comment: In the context of probability theory, the elements of a σ-algebra are called events (;&39&!/). Proposition 2.2 Let be an algebra of subsets of X. Then, contains X, the empty set, and it is closed under finite intersections. A A 8 Chapter 2 Proof : Since is not empty, it contains at least one set A . Then, A X A Ac and Xc ∈ A. Let A1,...,An . By= de∪ Morgan’s∈ A laws, = ∈ A n n c ⊂ A c Ak Ak . -

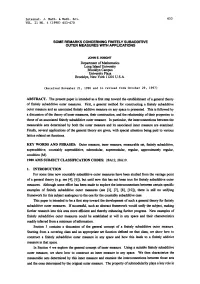

SOME REMARKS CONCERNING FINITELY Subaddmve OUTER MEASURES with APPUCATIONS

Internat. J. Math. & Math. Sci. 653 VOL. 21 NO. 4 (1998) 653-670 SOME REMARKS CONCERNING FINITELY SUBADDmVE OUTER MEASURES WITH APPUCATIONS JOHN E. KNIGHT Department of Mathematics Long Island University Brooklyn Campus University Plaza Brooklyn, New York 11201 U.S.A. (Received November 21, 1996 and in revised form October 29, 1997) ABSTRACT. The present paper is intended as a first step toward the establishment of a general theory of finitely subadditive outer measures. First, a general method for constructing a finitely subadditive outer measure and an associated finitely additive measure on any space is presented. This is followed by a discussion of the theory of inner measures, their construction, and the relationship of their properties to those of an associated finitely subadditive outer measure. In particular, the interconnections between the measurable sets determined by both the outer measure and its associated inner measure are examined. Finally, several applications of the general theory are given, with special attention being paid to various lattice related set functions. KEY WORDS AND PHRASES: Outer measure, inner measure, measurable set, finitely subadditive, superadditive, countably superadditive, submodular, supermodular, regular, approximately regular, condition (M). 1980 AMS SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION CODES: 28A12, 28A10. 1. INTRODUCTION For some time now countably subadditive outer measures have been studied from the vantage point of a general theory (e.g. see [4], [6]), but until now this has not been true for finitely subadditive outer measures. Although some effort has been made to explore the interconnections between certain specific examples of finitely subadditive outer measures (see [3], [7], [8], [10]), there is still no unifying framework for this subject analogous to the one for the countably subadditive case. -

Structural Features of the Real and Rational Numbers ENCYCLOPEDIA of MATHEMATICS and ITS APPLICATIONS

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS AND ITS APPLICATIONS FOUNDED BY G.-C. ROTA Editorial Board P. Flajolet, M. Ismail, E. Lutwak Volume 112 The Classical Fields: Structural Features of the Real and Rational Numbers ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS AND ITS APPLICATIONS FOUNDING EDITOR G.-C. ROTA Editorial Board P. Flajolet, M. Ismail, E. Lutwak 40 N. White (ed.) Matroid Applications 41 S. Sakai Operator Algebras in Dynamical Systems 42 W. Hodges Basic Model Theory 43 H. Stahl and V. Totik General Orthogonal Polynomials 45 G. Da Prato and J. Zabczyk Stochastic Equations in Infinite Dimensions 46 A. Bj¨orner et al. Oriented Matroids 47 G. Edgar and L. Sucheston Stopping Times and Directed Processes 48 C. Sims Computation with Finitely Presented Groups 49 T. Palmer Banach Algebras and the General Theory of *-Algebras I 50 F. Borceux Handbook of Categorical Algebra I 51 F. Borceux Handbook of Categorical Algebra II 52 F. Borceux Handbook of Categorical Algebra III 53 V. F. Kolchin Random Graphs 54 A. Katok and B. Hasselblatt Introduction to the Modern Theory of Dynamical Systems 55 V. N. Sachkov Combinatorial Methods in Discrete Mathematics 56 V. N. Sachkov Probabilistic Methods in Discrete Mathematics 57 P. M. Cohn Skew Fields 58 R. Gardner Geometric Tomography 59 G. A. Baker, Jr., and P. Graves-Morris Pade´ Approximants, 2nd edn 60 J. Krajicek Bounded Arithmetic, Propositional Logic, and Complexity Theory 61 H. Groemer Geometric Applications of Fourier Series and Spherical Harmonics 62 H. O. Fattorini Infinite Dimensional Optimization and Control Theory 63 A. C. Thompson Minkowski Geometry 64 R. B. Bapat and T. -

2.5 Outer Measure and Measurable Sets. Note the Results of This Section Concern Any Given Outer Measure Λ

2.5 Outer Measure and Measurable sets. Note The results of this section concern any given outer measure ¸. If an outer measure ¸ on a set X were a measure then it would be additive. In particular, given any two sets A; B ⊆ X we have that A \ B and A \ Bc are disjoint with (A \ B) [ (A \ Bc) = A and so we would have ¸(A) = ¸(A \ B) + ¸(A \ Bc): We will see later that this does not necessarily hold for all A and B but it does lead to the following definition. Definition Let ¸ be an outer measure on a set X. Then E ⊆ X is said to be measurable with respect to ¸ (or ¸-measurable) if ¸(A) = ¸(A \ E) + ¸(A \ Ec) for all A ⊆ X. (7) (This can be read as saying that we take each and every possible “test set”, A, look at the measures of the parts of A that fall within and without E, and check whether these measures add up to that of A.) Since ¸ is subadditive we have ¸(A) · ¸(A\E)+¸(A\Ec) so, in checking measurability, we need only verify that ¸(A) ¸ ¸(A \ E) + ¸(A \ Ec) for all A ⊆ X. (8) Let M = M(¸) denote the collection of ¸-measurable sets. Theorem 2.6 M is a field. Proof Trivially Á and X are in M. Take any E1;E2 2 M and any test set A ⊆ X. Then c ¸(A) = ¸(A \ E1) + ¸(A \ E1): c Now apply the definition of measurability for E2 with the test set A \ E1 to get c c c c ¸(A \ E1) = ¸((A \ E1) \ E2) + ¸((A \ E1) \ E2) c c = ¸(A \ E1 \ E2) + ¸(A \ (E1 [ E2) ): Combining c c ¸(A) = ¸(A \ E1) + ¸(A \ E1 \ E2) + ¸(A \ (E1 [ E2) ): (9) 1 We hope to use the subadditivity of ¸ on the first two term on the right hand side of (9). -

2.1.3 Outer Measures and Construction of Measures Recall the Construction of Lebesgue Measure on the Real Line

CHAPTER 2. THE LEBESGUE INTEGRAL I 11 2.1.3 Outer measures and construction of measures Recall the construction of Lebesgue measure on the real line. There are various approaches to construct the Lebesgue measure on the real line. For example, consider the collection of finite union of sets of the form ]a; b]; ] − 1; b]; ]a; 1[ R: This collection is an algebra A but not a sigma-algebra (this has been discussed on p.7). A natural measure on A is given by the length of an interval. One attempts to measure the size of any subset S of R covering it by countably many intervals (recall also that R can be covered by countably many intervals) and we define this quantity by 1 1 X [ m∗(S) = inff jAkj : Ak 2 A;S ⊂ Akg (2.7) k=1 k=1 where jAkj denotes the length of the interval Ak. However, m∗(S) is not a measure since it is not additive, which we do not prove here. It is only sigma- subadditive, that is k k [ X m∗ Sn ≤ m∗(Sn) n=1 n=1 for any countable collection (Sn) of subsets of R. Alternatively one could choose coverings by open intervals (see the exercises, see also B.Dacorogna, Analyse avanc´eepour math´ematiciens)Note that the quantity m∗ coincides with the length for any set in A, that is the measure on A (this is surprisingly the more difficult part!). Also note that the sigma-subadditivity implies that m∗(A) = 0 for any countable set since m∗(fpg) = 0 for any p 2 R. -

Finitely Subadditive Outer Measures, Finitely Superadditive Inner Measures and Their Measurable Sets

Internat. J. Math. & Math. Sci. 461 VOL. 19 NO. 3 (1996) 461-472 FINITELY SUBADDITIVE OUTER MEASURES, FINITELY SUPERADDITIVE INNER MEASURES AND THEIR MEASURABLE SETS P. D. STRATIGOS Department of Mathematics Long Island University Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA (Received February 24, 1994 and in revised form April 28, 1995) ABSTRACT. Consider any set X A finitely subadditive outer measure on P(X) is defined to be a function u from 7(X) to R such that u()) 0 and u is increasing and finitely subadditive A finitely superadditive inner measure on 7:'(X) is defined to be a function p from (X) to R such that p(0) 0 and p is increasing and finitely superadditive (for disjoint unions) (It is to be noted that every finitely superadditive inner measure on 7(X) is countably superadditive This paper contributes to the study of finitely subadditive outer measures on P(X) and finitely superadditive inner measures on 7:'(X) and their measurable sets KEY WORDS AND PHRASES. Lattice space, lattice normality and countable compactness, lattice regularity and a-smoothness of a measure, finitely subadditive outer measure, finitely superadditive inner measure, regularity of a finitely subadditive outer measure 1991 AMS SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION CODES. 28A12, 28A60, 28C15 0. INTROI)UCTION Consider any set X and any lattice on X, The algebra on X generated by is denoted by .A() A measure on .A(/2) is defined to be a function/.t from Jl.() to R such that/.t is finitely additive and bounded. The set of all measures on .A() is denoted by M() and the set of all/-regular measures on Jr(/2) by M/(/2) A finitely subadditive outer measure on 7)(X) is defined to be a function u from '(X) to R such that u(0) 0 and u is increasing and finitely subadditive A finitely superadditive inner measure on P(X) is defined to be a function p from P(X) to R such that p() 0 and p is increasing and finitely superadditive (for disjoint unions).