Public–Private Partnership Monitor: Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riders Digest 2019

RIDERS DIGEST 2019 PHILIPPINE EDITION Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. OFFICES NATIONWIDE LEGEND: RLB Phils., Inc Office: • Manila • Sta Rosa, Laguna • Cebu • Davao • Cagayan de Oro • Bacolod • Iloilo • Bohol • Subic • Clark RLB Future Expansions: • Dumaguete • General Santos RIDERS DIGEST PHILIPPINES 2019 A compilation of cost data and related information on the Construction Industry in the Philippines. Compiled by: Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. A proud member of Rider Levett Bucknall Group Main Office: Bacolod Office: Building 3, Corazon Clemeña 2nd Floor, Mayfair Plaza, Compound No. 54 Danny Floro Lacson cor. 12th Street, Street, Bagong Ilog, Pasig City 1600 Bacolod City, Negros Occidental Philippines 6100 Philippines T: +63 2 234 0141/234 0129 T: +63 34 432 1344 +63 2 687 1075 E: [email protected] F: +63 2 570 4025 E: [email protected] Iloilo Office: 2nd Floor (Door 21) Uy Bico Building, Sta. Rosa, Laguna Office: Yulo Street. Iloilo Unit 201, Brain Train Center City Proper, Iloilo, 5000 Lot 11 Block 3, Sta. Rosa Business Philippines Park, Greenfield Brgy. Don Jose, Sta. T:+63 33 320 0945 Rosa City Laguna, 4026 Philippines E: [email protected] M: +63 922 806 7507 E: [email protected] Cagayan de Oro Office: Rm. 702, 7th Floor, TTK Tower Cebu Office: Don Apolinar Velez Street Brgy. 19 Suite 602, PDI Condominium Cagayan De Oro City Archbishop Reyes Ave. corner J. 9000 Philippines Panis Street, Banilad, Cebu City, 6014 T: +63 88 8563734 Philippines M: +63 998 573 2107 T: +63 32 268 0072 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Subic Office: Davao Office: The Venue Bldg. -

Transportation History of the Philippines

Transportation history of the Philippines This article describes the various forms of transportation in the Philippines. Despite the physical barriers that can hamper overall transport development in the country, the Philippines has found ways to create and integrate an extensive transportation system that connects the over 7,000 islands that surround the archipelago, and it has shown that through the Filipinos' ingenuity and creativity, they have created several transport forms that are unique to the country. Contents • 1 Land transportation o 1.1 Road System 1.1.1 Main highways 1.1.2 Expressways o 1.2 Mass Transit 1.2.1 Bus Companies 1.2.2 Within Metro Manila 1.2.3 Provincial 1.2.4 Jeepney 1.2.5 Railways 1.2.6 Other Forms of Mass Transit • 2 Water transportation o 2.1 Ports and harbors o 2.2 River ferries o 2.3 Shipping companies • 3 Air transportation o 3.1 International gateways o 3.2 Local airlines • 4 History o 4.1 1940s 4.1.1 Vehicles 4.1.2 Railways 4.1.3 Roads • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 External links Land transportation Road System The Philippines has 199,950 kilometers (124,249 miles) of roads, of which 39,590 kilometers (24,601 miles) are paved. As of 2004, the total length of the non-toll road network was reported to be 202,860 km, with the following breakdown according to type: • National roads - 15% • Provincial roads - 13% • City and municipal roads - 12% • Barangay (barrio) roads - 60% Road classification is based primarily on administrative responsibilities (with the exception of barangays), i.e., which level of government built and funded the roads. -

Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using Pagerank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2

“Transportation for A Better Life: Harnessing Finance for Safety and Equity in AEC August 21, 2015, Bangkok, Thailand Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using PageRank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2 1Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We attempt to identify the different node hubs of a road network using PageRank for preparation for possible random terrorist attacks. The robustness of a road network against such attack is crucial to be studied because it may cripple its connectivity by simply shutting down these hubs. We show the important hubs in a road network based on network structure and propose a model for robustness analysis. By identifying important hubs in a road network, possible preparation schemes may be done earlier to mitigate random terrorist attacks, including defense reinforcement and transportation security. A case study of the Metro Manila road network is also presented. The case study shows that the most important hubs in the Metro Manila road network are near airports, piers, major highways and expressways. Keywords: PageRank, Terrorist Attack, Robustness 1. Introduction Table 1 Comparative analysis of different Roads are important access points because methodologies on network robustness indices connects different places like cities, districts, and Author Method Strength Weakness landmarks. -

AFE-ADB News No 43.Indd

No. 43 | September 2013 The Newsletter of the Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank Delhi Annual General Meeting People, Places and Passages Chapter News IN THIS ISSUE Our Cover No. 43 | September 2013 SEPTEMBER 2013 The Newsletter of the Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank 3 AFE–ADB Updates 3 From the AFE President Delhi Annual General Meeting 3 Chapter Coordinators 4 What’s New at HQ?: Professor Yasutomo on ADB’s Beginnings People, Places and Passages Chapter News 6 Delhi 2013 6 Chapter Coordinators’ Meeting 9 AFE–ADB 27th Annual General Meeting 12 Cocktails 15 Participants Top right: ADB President Takehiko Nakao, 16 Around Delhi former ADB President (and new AFE member) Haruhiko Kuroda, and AFE Chair 19 Chapter News Bong-Suh Lee at the AFE Cocktail Left: “See Through” by Bill Staub 19 Indonesia Below: At the New Zealand Chapter gathering 20 New Zealand: Art Deco, Wine, and More 21 Washington DC 22 People, Places, and Passages AFE–ADB News 22 Connections: Bill Staub’s Art 25 Standing on Their Own (Jaipur) Feet Publisher: Hans-Juergen Springer 27 News Briefs 28 A Letter from the Governor Publications Committee: Jill Gale de Villa (head), 30 North to Anvaya Cove Gam de Armas, Wickie Mercado, Stephen 31 Fifty Years and Still Counting Banta, David Parker, Hans-Juergen Springer 32 Travel and Writing 33 A Walk in the Wilds Graphic Assistance: Jo Jacinto-Aquino 35 Friendship, Food, and Fun at CalloSpa Photographs: ADB Photobank, ADB Security Unit, 36 Humanitarian Ethel Raquel Cabiles, Adrian Davis, Daisy de Chavez, 37 AFE Finland Gathering Graham James Dwyer, Estrellita Gamboa, Ian 37 AFE–ADB Committees Gill, Midi Diel Kawashima, V.R. -

Results Report 2014

Results Report 2014 Results Report 2014 26th February, 2015 Non Audited Figures 1 Results Report 2014 INDEX 1 Executive Summary 3 1.1 Main figures 3 1.2 Relevant facts 5 2 Consolidated Financial Statements 8 2.1 Income Statement 8 2.1.1 Sales and Backlog 8 2.1.2 Operating Results 10 2.1.3 Financial Results 11 2.1.4 Net Profit Attributable to the Parent Company 12 2.2 Consolidated Balance Sheet 13 2.2.1 Non-Current Assets 13 2.2.2 Assets held for sale 14 2.2.3 Working Capital 15 2.2.4 Net Debt 15 2.2.5 Net Worth 16 2.3 Net Cash Flows 17 2.3.1 Operating Activities 17 2.3.2 Investments 18 2.3.3 Other Cash Flows 18 3 Areas of Activity Evolution 19 3.1 Construction 19 3.2 Industrial Services 22 3.3 Environment 24 4 Relevant facts after the end of the period 26 5 Description of the main risks and opportunities 26 6 Corporate Social Responsibility 28 6.1 Ethics 28 6.2 Efficiency 28 6.3 Employees 30 7 Information on affiliates 30 8 Annexes 31 8.1 Main figures per area of activity 31 8.2 Financial Accounts per area of Activity 32 8.2.1 Income Statement 32 8.2.2 Balance Sheet 33 8.3 Infrastructure Concessions 34 8.4 Share data 35 8.5 Exchange rate effect 36 8.6 Main Awards of the Period 37 8.6.1 Construction 37 8.6.2 Industrial Services 40 8.6.3 Environment 41 Non Audited Figures 2 Results Report 2014 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Main figures Grupo ACS Key operating & financial figures Million Euro 2013 2014 Var. -

Where Is My New Servicing Branch Located and How Can I Contact The

Where is my HSBC Ortigas Branch currently located at GF/29F Discovery Suites, ADB Avenue, new servicing Ortigas Center, San Antonio, Pasig City will be relocated to the Lower Ground Level, branch located Shangri-La Plaza East Wing, EDSA corner Shaw Boulevard, Mandaluyong City on and how can I January 4, 2021. You may call HSBC Ortigas Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581- contact the 7903 or (+632) 8581-7435 for any questions. branch? HSBC Quezon City Branch will be permanently closed on December 29, 2020 and client accounts will be transferred to the new location of HSBC Ortigas Branch. You may call HSBC Quezon City Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581-7928 or (+632) 8581-7822 until December 29. 2020. Starting January 4, 2021, you may call HSBC Ortigas Branch through phone numbers mentioned above. HSBC Binondo Branch will be permanently closed on February 16, 2021 and accounts will be transferred to HSBC Makati Branch located at GF, Tower 1, The Enterprise Center, Ayala Avenue corner Paseo de Roxas, Makati City. You may call HSBC Binondo Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581-7249 or (+632) 8581-8198 until February 16, 2021. Starting February 17, 2021, you may call HSBC Makati Branch through phone numbers (+632) 8581-7787 or (+632) 8581-8097. How does this Your account will be automatically transferred into the branches specified above. affect us There will be no impact on how you transact your account which you can do in any of (customers)? our 5 HSBC branches: Makati, BGC, Ortigas, Cebu, and Davao. Do I need to do However, if you have a Safe Deposit Box in Ortigas Branch, Quezon City Branch or anything? Binondo Branch, please refer to the instructions on retrieval of your Safe Deposit Box (SDB) contents. -

1623400766-2020-Sec17a.Pdf

COVER SHEET 2 0 5 7 3 SEC Registration Number M E T R O P O L I T A N B A N K & T R U S T C O M P A N Y (Company’s Full Name) M e t r o b a n k P l a z a , S e n . G i l P u y a t A v e n u e , U r d a n e t a V i l l a g e , M a k a t i C i t y , M e t r o M a n i l a (Business Address: No. Street City/Town/Province) RENATO K. DE BORJA, JR. 8898-8805 (Contact Person) (Company Telephone Number) 1 2 3 1 1 7 - A 0 4 2 8 Month Day (Form Type) Month Day (Fiscal Year) (Annual Meeting) NONE (Secondary License Type, If Applicable) Corporation Finance Department Dept. Requiring this Doc. Amended Articles Number/Section Total Amount of Borrowings 2,999 as of 12-31-2020 Total No. of Stockholders Domestic Foreign To be accomplished by SEC Personnel concerned File Number LCU Document ID Cashier S T A M P S Remarks: Please use BLACK ink for scanning purposes. 2 SEC Number 20573 File Number______ METROPOLITAN BANK & TRUST COMPANY (Company’s Full Name) Metrobank Plaza, Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Urdaneta Village, Makati City, Metro Manila (Company’s Address) 8898-8805 (Telephone Number) December 31 (Fiscal year ending) FORM 17-A (ANNUAL REPORT) (Form Type) (Amendment Designation, if applicable) December 31, 2020 (Period Ended Date) None (Secondary License Type and File Number) 3 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. -

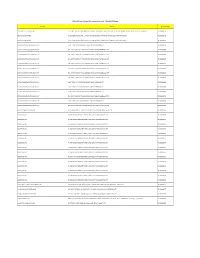

DOLE-NCR for Release AEP Transactions As of 7-16-2020 12.05Pm

DOLE-NCR For Release AEP Transactions as of 7-16-2020 12.05pm Company Address Transaction No. 3M SERVICE CENTER APAC, INC. 17TH, 18TH, 19TH FLOORS, BONIFACIO STOPOVER CORPORATE CENTER, 31ST STREET COR., 2ND AVENUE, BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY, TAGUIG CITY TNCR20000756 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000178 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000283 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000536 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000554 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000569 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000607 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000617 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000632 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000633 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000638 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000680 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY -

A Case Study on Philippine Cities' Initiatives

A Case Study of Philippine Cities’ Initiatives | June – December 2017 © KCDDYangot /WWF-Philippines | Sustainable Urban Mobility — Philippine Cities’ Initiatives © IBellen / WWF-Philippines ACKNOWLEDGMENT WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF-Philippines has been working as a national organization of the WWF network since 1997. As the 26th national organization in the network, WWF-Philippines has successfully been implementing various conservation projects to help protect some of the most biologically-significant ecosystems in Asia. Our mission is to stop, and eventually reverse the accelerating degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature. The Sustainable Urban Mobility: A Case Study of Philippine Cities’ Initiatives is undertaken as part of the One Planet City Challenge (OPCC) 2017-2018 project. Project Manager: Imee S. Bellen Researcher: Karminn Cheryl Dinney Yangot WWF-Philippines acknowledges and appreciates the assistance extended to the case study by the numerous respondents and interviewees, particularly the following: Baguio City City Mayor Mauricio Domogan City Environment and Parks Management Officer, Engineer Cordelia Lacsamana City Tourism Officer, Jose Maria Rivera Department of Tourism, Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) Regional Director Marie Venus Tan Federation of Jeepney Operators and Drivers Associations—Baguio-Benguet-La Union (FEJODABBLU) Regional President Mr. Perfecto F. Itliong, Jr. Cebu City City Mayor Tomas Osmeña City Administrator, Engr. Nigel Paul Villarete City Environment and Natural Resources Officer, Ma. Nida Cabrera Cebu City BRT Project Manager, Atty. -

Preliminary Information Statement

07 Februaary 2018 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosure Department 3/F PSE Plaza, Ayala Triangle Plaza Makati City, Metro Manila Attention: Mr. Jose Valeriano B. Zuño III OIC ‐ Disclosure Department Philippine Stock Exchange Sir: Please find attached Preliminary Information Statement (SEC Form IS‐20) submitted to the Commission today for its consideration and approval in relation to the Company’s Annual Stockholders’ Meeting on March 15, 2018 in Davao City, Philippines. Thank you and warm regards. Very truly yours, Atty. Socorro Ermac Cabreros Corporate Secretary Page 2 of 48 SEC Form IS-20 Page 3 of 48 SEC Form IS-20 PART I. INFORMATION REQUIRED IN INFORMATION STATEMENT A. GENERAL INFORMATION Item 1. Date, time and place of meeting of security holders (a) Date : March 15, 2018 Time : 2:00 p.m . Place : Phoenix Petroleum Corporate Headquarters Stella Hizon Reyes Rd. Davao City Mailing P-H-O-E-N-I-X PETROLEUM PHILIPPINES, INC. Address: Office of the Corporate Secretary Phoenix Petroleum Corporate Headquarters Stella Hizon Reyes Road, Bo. Pampanga Lanang, Davao City 8000 (b) Approximate date on which the Information Statement is first to be sent or given to security holders: February 22, 2018. Item 2. Dissenter ’s Right of Appraisal Procedure for the exercise of Appraisal Right Pursuant to Section 81 of the Corporation Code of the Philippines, a stockholder has the right to dissent and demand payment of the fair value of his shares in case of any amendment to the articles of incorporation that, (1) in case of amendment to the articles of incorporation, has the effect of changing or restricting the rights of any stockholder or class of shares, or of authorizing preferences in any respect superior to those of outstanding shares of any class, or of extending or shortening the term of corporate existence; (2) in case of lease, exchange, transfer, mortgage, pledge or other disposition of all or substantially all of the corporate property and assets as provided in the Corporation Code, and (3) in case of merger or consolidation. -

Art of Nation Building

SINING-BAYAN: ART OF NATION BUILDING Social Artistry Fieldbook to Promote Good Citizenship Values for Prosperity and Integrity PHILIPPINE COPYRIGHT 2009 by the United Nations Development Programme Philippines, Makati City, Philippines, UP National College of Public Administration and Governance, Quezon City and Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation, Inc. Edited by Vicente D. Mariano Editorial Assistant: Maricel T. Fernandez Border Design by Alma Quinto Project Director: Alex B. Brillantes Jr. Resident Social Artist: Joey Ayala Project Coordinator: Pauline S. Bautista Siningbayan Pilot Team: Joey Ayala, Pauline Bautista, Jaku Ayala Production Team: Joey Ayala Pauline Bautista Maricel Fernandez Jaku Ayala Ma. Cristina Aguinaldo Mercedita Miranda Vincent Silarde ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of research or review, as permitted under the copyright, this book is subject to the condition that it should not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, sold, or circulated in any form, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by applied laws. ALL SONGS COPYRIGHT Joey Ayala PRINTED IN THE PHILIPPINES by JAPI Printzone, Corp. Text Set in Garamond ISBN 978 971 94150 1 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS i MESSAGE Mary Ann Fernandez-Mendoza Commissioner, Civil Service Commission ii FOREWORD Bro. Rolando Dizon, FSC Chair, National Congress on Good Citizenship iv PREFACE: Siningbayan: Art of Nation Building Alex B. Brillantes, Jr. Dean, UP-NCPAG vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii INTRODUCTION Joey Ayala President, Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation Inc.(BLAFI) 1 Musical Reflection: KUNG KAYA MONG ISIPIN Joey Ayala 2 SININGBAYAN Joey Ayala 5 PART I : PAGSASALOOB (CONTEMPLACY) 9 “BUILDING THE GOOD SOCIETY WE WANT” My Hope as a Teacher in Political and Governance Jose V. -

Project Implementation Plan

CHAPTER 5 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN The Supplementary Survey on North South Commuter Rail Project (Phase II-A) in the Republic of the Philippines FINAL REPORT CHAPTER 5 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLANNING 5.1 Examination of Preliminary Construction Plan The construction of NSCR will require careful planning and organization, given the magnitude of the works, time constraints and the location of the works on busy national and arterial roads within Metropolitan Manila and Bulacan Province. 5.1.1 Temporary Works 1) Temporary Access to Site It is necessary to apply countermeasures flooding during heavy rain season because of the low ground level between Malolos and Caloocan. There is no problem with an access road to the site along the main road in this area. However, it is necessary to consider to construct temporary access to site far from main roads. In swampy areas between Malolos and San Fernando along the PNR Route, it is necessary to construct a temporary steel stage for machinery or materials transportation during construction. It is necessary to install sheet piles to avoid an intrusion of ground water during construction of the substructure. 2) Sufficient Space for the Works There are some narrow ROW sections between Malolos and Caloocan along the PNR Route. During construction of elevated structures, it is necessary to have more than 15m width for access road to secure access of many trucks, truck mixers and other construction equipment transportation to the site. After construction, the temporary access shall be maintained more than 15m width as a service road for maintenance or emergency evacuation. Source: JICA Study Team Figure 5.1.1 Necessary ROW for Elevated Structures 5-1 5.1.2 Viaduct 5.1.2.1 Foundations Viaduct foundations comprise of conventional bored piles and pile caps.