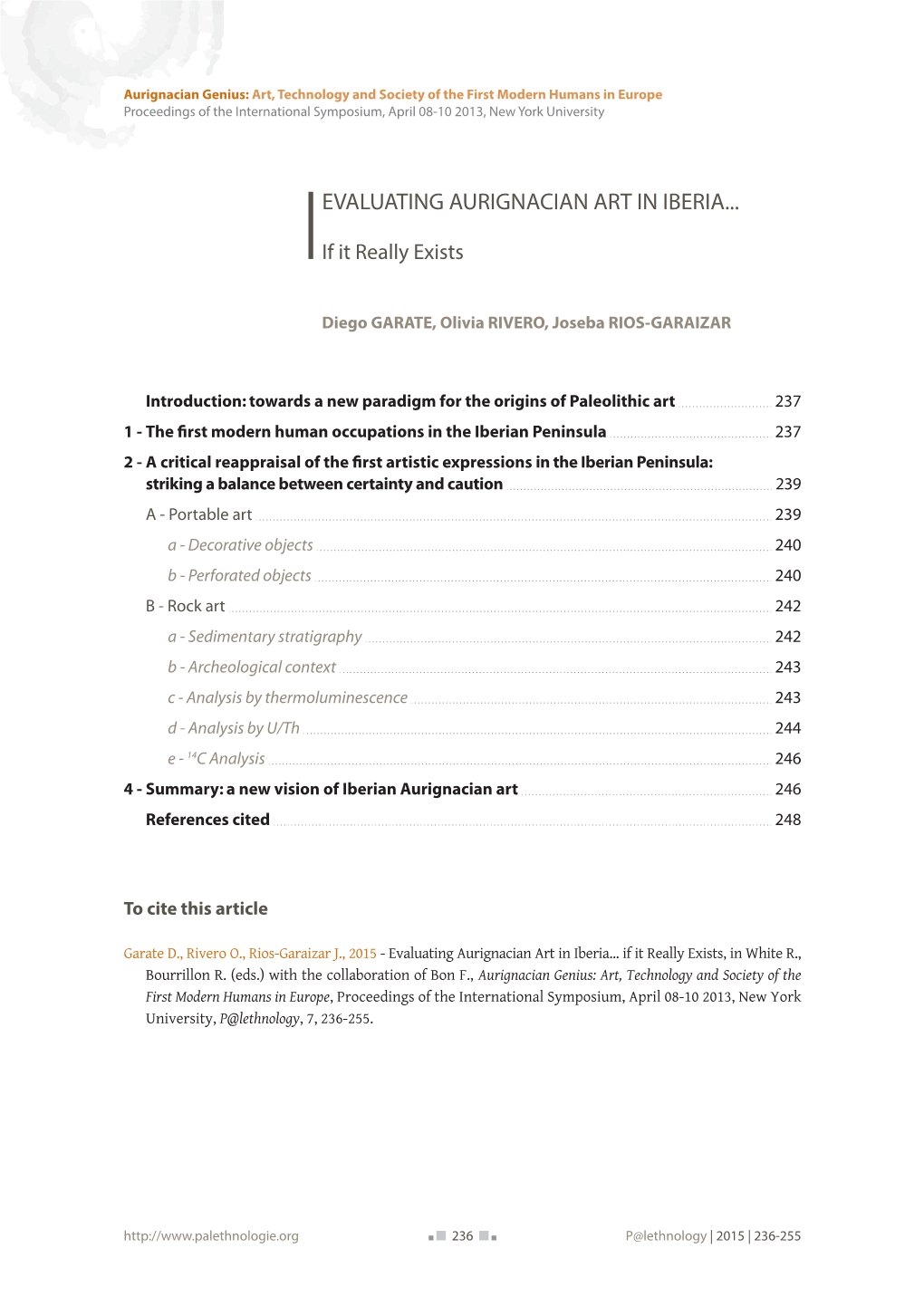

Evaluating Aurignacian Art in Iberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Dating Aurignacian Rock Art in Altxerri B Cave (Northern Spain)

Journal of Human Evolution 65 (2013) 457e464 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Not only Chauvet: Dating Aurignacian rock art in Altxerri B Cave (northern Spain) C. González-Sainz a, A. Ruiz-Redondo a,*, D. Garate-Maidagan b, E. Iriarte-Avilés c a Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Avenida de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain b CREAP Cartailhac-TRACES-UMR 5608, University de Toulouse-Le Mirail, 5 allées Antonio Machado, 31058 Toulouse Cedex 9, France c Laboratorio de Evolución Humana, Dpto. CC. Históricas y Geografía, University de Burgos, Plaza de Misael Bañuelos s/n, Edificio IþDþi, 09001 Burgos, Spain article info abstract Article history: The discovery and first dates of the paintings in Grotte Chauvet provoked a new debate on the origin and Received 29 May 2013 characteristics of the first figurative Palaeolithic art. Since then, other art ensembles in France and Italy Accepted 2 August 2013 (Aldène, Fumane, Arcy-sur-Cure and Castanet) have enlarged our knowledge of graphic activity in the early Available online 3 September 2013 Upper Palaeolithic. This paper presents a chronological assessment of the Palaeolithic parietal ensemble in Altxerri B (northern Spain). When the study began in 2011, one of our main objectives was to determine the Keywords: age of this pictorial phase in the cave. Archaeological, geological and stylistic evidence, together with Upper Palaeolithic radiometric dates, suggest an Aurignacian chronology for this art. The ensemble in Altxerri B can therefore Radiocarbon dating Cantabrian region be added to the small but growing number of sites dated in this period, corroborating the hypothesis of fi Cave painting more complex and varied gurative art than had been supposed in the early Upper Palaeolithic. -

Assessing Relationships Between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology Via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling William E

Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco-cultural niche modeling William E. Banks To cite this version: William E. Banks. Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco- cultural niche modeling. Archaeology and Prehistory. Universite Bordeaux 1, 2013. hal-01840898 HAL Id: hal-01840898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01840898 Submitted on 11 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse d'Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Université de Bordeaux 1 William E. BANKS UMR 5199 PACEA – De la Préhistoire à l'Actuel : Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie Assessing Relationships between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling Soutenue le 14 novembre 2013 devant un jury composé de: Michel CRUCIFIX, Chargé de Cours à l'Université catholique de Louvain, Belgique Francesco D'ERRICO, Directeur de Recherche au CRNS, Talence Jacques JAUBERT, Professeur à l'Université de Bordeaux 1, Talence Rémy PETIT, Directeur de Recherche à l'INRA, Cestas Pierre SEPULCHRE, Chargé de Recherche au CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette Jean-Denis VIGNE, Directeur de Recherche au CNRS, Paris Table of Contents Summary of Past Research Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Shara E

CURRICULUM VITAE Shara E. Bailey July 2019 Home Address: 14 Lancaster Avenue Office Address: New York University Maplewood, NJ 07040 Department of Anthropology 25 Waverly Place Mobile Phone: 646.300.4508 New York, NY 10003 E-mail: [email protected] Office Phone: 212.998.8576 Education Arizona State University, Department of Anthropology, Tempe, AZ PhD in Anthropology Jan 2002 Dissertation Title: Neandertal Dental Morphology: Implications for Modern Human Origins Dissertation director: Prof. William H. Kimbel Master of Arts in Anthropology 1995 Thesis Title: Population distribution of the tuberculum dentale complex and anomalies of the anterior maxillary teeth. Thesis director: Regents’ Professor, Christy G. Turner, II Temple University, Philadelphia, PA Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and Anthropology 1992 Positions/Affiliations Associate Professor, New York University, Department of Anthropology, New York, NY 2011- Associated Scientist, Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary 2006- Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany Assistant Professor, New York University, Department of Anthropology, New York, NY 2005-2011 Research Scientist, The Max Planck Institute, Department of Human Evolution, 2004-2006 Leipzig, Germany Postdoctoral Research Associate (Prof. Bernard Wood, Research Director) 2002-2004 The George Washington University, CASHP, Washington DC Appointments Associate Chair, Anthropology Department 2018- New York University, College of Arts and Sciences Director of Undergraduate Studies, Anthropology Department 2016-2018 -

Cost Units to Understand Flint Procurement Strategies During The

Stones in Motion: Cost units to understand flint procurement strategies during the Upper Palaeolithic in the south-western Pyrenees using GIS Alejandro Prieto, Maite García-Rojas, Aitor Sánchez, Aitor Calvo, Eder Domínguez-Ballesteros, Javier Ordoño, Maite Iris García-Collado Department of Geography, Prehistory and Archaeology. Faculty of Arts, University of the Basque Country. Tomás y Valiente Street N/N, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. Email: Prieto: [email protected]; García-Rojas: [email protected]; Sánchez: [email protected]; Calvo: [email protected]; Domínguez-Ballesteros: [email protected]; Ordoño: [email protected]; García-Collado: [email protected] Abstract: Studies on lithic resource management –mainly flint– by prehistoric groups south of the western Pyrenees have significantly increased during the past decades. These studies usually focus on identifying outcrops and characterising the different varieties found at archaeological sites. However, the understanding of mobility and territorial management patterns based on raw materials is still very limited and has only been tackled in terms of lineal distance. This paper proposes a methodological approach for the territorial analysis of flint distribution with the three following aims: 1) to determine the expansion ranges of each variety of flint from its outcrop; 2) to spatially relate these outcrops with archaeological sites; and 3) to improve our knowledge on the catchment strategies of Upper Palaeolithic groups. The methodological tool chosen to fulfil these objectives is the Geographic Information System (GIS), because it allows to relate spatially the flint outcrops and flint varieties identified at archaeological sites based on: 1) isocost maps showing the cost of expansion for each variety of flint across the territory built on topography; 2) the quantification of the cost of expansion using Cost Units (CU); and 3) the relationship between the percentage of each variety of flint at each archaeological site and the cost of accessing its outcrop. -

SIG02 Bullen

CLOTTES J. (dir.) 2012. — L’art pléistocène dans le monde / Pleistocene art of the world / Arte pleistoceno en el mundo Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010 – Symposium « Signes, symboles, mythes et idéologie… » Finding the first intentional mark makers: Clues in brain development Margaret BULLEN* Keywords: Marks; Intentionality; cognition; synapse. “‘Lascaux Man’ created and created out of nothing, this world of art in which communication between individual minds begins.” (Bataille 1955: 11) Lascaux was, for Bataille, the “birth of art” despite the fact that when it was found by school boys in 1940, it was far from the first painted cave to be discovered. Altamira was almost as famous for its initial rejection by Cartailhac in the 1870s and his later acknowledgement of its being genuinely Palaeolithic, as for its bison curled into recesses in the ceiling; Altamira, La Mouthe, Les Combarelles, Font de Gaume and Niaux are just a few of the caves with paintings already, long before 1940, accepted as being from the Upper Palaeolithic (Bahn 1997 ; Grand 1967). Yet Bataille, a noted French philosopher could still perceive Lascaux as the “end to that timeless deadlock” and “the shift from the world of work to the world of play, from the rough hewn to the finished individual being.” (Bataille 1955: 27). But this is not where or when it all began Here I will endevour to reach back to a time before the creation of the bison, lionesses, horses and reindeer, which “stimulate multiple distributed cerebral processors in a novel and harmonious way” (Dehaene 2009: 309) and which we acknowledge as masterpieces. -

Sorting the Ibex from the Goats in Portugal Robert G

Sorting the ibex from the goats in Portugal Robert G. Bednarik An article by António Martinho Baptista (2000) in the light-weight rock art magazine Adoranten1 raises a number of fascinating issues about taxonomy. The archaeological explanations so far offered for a series of rock art sites in the Douro basin of northern Portugal and adjacent parts of Spain contrast with the scientific evidence secured to date from these sites. This includes especially archaeozoological, geomorphological, sedimentary, palaeontological, dating and especially analytical data from the art itself. For instance one of the key arguments in favour of a Pleistocene age of fauna depicted along the Côa is the claim that ibex became extinct in the region with the end of the Pleistocene. This is obviously false. Not only do ibex still occur in the mountains of the Douro basin—even if their numbers have been decimated—they existed there throughout the Holocene. More relevantly, the German achaeozoologist T. W. Wyrwoll (2000) has pointed out that all the ibex-like figures in the Côa valley resemble Capra ibex lusitanica or victoriae. The Portuguese ibex, C. i. lusitanica, became extinct only in 1892, and not as Zilhão (1995) implies at the end of the Pleistocene. The Gredos ibex (C. i. victoriae) still survives in the region. The body markings depicted on one of the Côa zoomorphs, a figure from Rego da Vide, resemble those found on C. i. victoriae so closely that this typical Holocene sub-species rather than a Pleistocene sub-species (notably Capra ibex pyrenaica) is almost certainly depicted (Figure 1). -

IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca Lucca, Italy Measuring Time Histories of Chronology Building in Archaeology Phd Program

IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca Lucca, Italy Measuring Time Histories of chronology building in archaeology PhD Program in Analysis and Management of Cultural Heritage XXX Cycle By Maria Emanuela Oddo 2020 The dissertation of Maria Emanuela Oddo is approved. PhD Program Coordinator: Prof. Emanuele Pellegrini, IMT School for advanced Studies Lucca Advisor: Prof. Maria Luisa Catoni Co-Advisor: Prof. Maurizio Harari The dissertation of Maria Emanuela Oddo has been reviewed by: Prof. Marcello Barbanera, University of Rome La Sapienza Prof. Silvia Paltineri, University of Padova IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca 2020 Contents Acknowledgements vii Vita ix Publications xii Presentations xiv Abstract xvi List of Figures xvii List of Tables xxi 0 Introduction 1 0.1 Archaeological chronologies 1 0.2 Histories of archaeological chronologies 3 0.3 Selection of case studies 5 1 La Grotte de la Verpillière, Germolles (FR) 13 1.1 Grotte de la Verpillière I 13 1.1.1 Charles Méray 15 1.1.2 Gabriel De Mortillet and la question Aurignacienne 23 1.1.3 Henri Breuil 35 1.1.4 Henri Delporte 40 1.1.5 Jean Combier 46 1.1.6 Harald Floss 48 1.1.7 Ten new radiocarbon dates at ORAU 58 1.2 Analyzing the debate 63 1.2.1 Neanderthals and Modern Humans 67 iii 1.2.2 The Aurignacian: unpacking a conceptual unit 76 1.2.3 Split-base points and the nature of ‘index fossils’ 85 1.3 Conclusions 96 2 The Fusco Necropolis, Syracuse (IT) 100 2.1 The Fusco Necropolis. An under-published reference site 118 2.1.1 Luigi Mauceri 119 2.1.2 Francesco Saverio Cavallari 140 -

Symbolic Territories in Pre-Magdalenian Art?

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321909484 Symbolic territories in pre-Magdalenian art? Article in Quaternary International · December 2017 DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.08.036 CITATION READS 1 61 2 authors, including: Eric Robert Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 37 PUBLICATIONS 56 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: An approach to Palaeolithic networks: the question of symbolic territories and their interpretation through Magdalenian art View project Karst and Landscape Heritage View project All content following this page was uploaded by Eric Robert on 16 July 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Quaternary International 503 (2019) 210e220 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Symbolic territories in pre-Magdalenian art? * Stephane Petrognani a, , Eric Robert b a UMR 7041 ArscAn, Ethnologie Prehistorique, Maison de l'Archeologie et de l'Ethnologie, Nanterre, France b Departement of Prehistory, Museum national d'Histoire naturelle, Musee de l'Homme, 17, place du Trocadero et du 11 novembre 75116, Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The legacy of specialists in Upper Paleolithic art shows a common point: a more or less clear separation Received 27 August 2016 between Magdalenian art and earlier symbolic manifestations. One of principal difficulty is due to little Received in revised form data firmly dated in the chronology for the “ancient” periods, even if recent studies precise chronological 20 June 2017 framework. Accepted 15 August 2017 There is a variability of the symbolic traditions from the advent of monumental art in Europe, and there are graphic elements crossing regional limits and asking the question of real symbolic territories existence. -

Isotopic Evidence for Dietary Ecology of Cave Lion (Panthera Spelaea

Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: Prey choice, competition and implications for extinction Hervé Bocherens, Dorothée G. Drucker, Dominique Bonjean, Anne Bridault, Nicolas Conard, Christophe Cupillard, Mietje Germonpré, Markus Höneisen, Suzanne Münzel, Hannes Napierala, et al. To cite this version: Hervé Bocherens, Dorothée G. Drucker, Dominique Bonjean, Anne Bridault, Nicolas Conard, et al.. Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: Prey choice, competition and implications for extinction. Quaternary International, Elsevier, 2011, 245 (2), pp.249-261. 10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.023. hal-01673488 HAL Id: hal-01673488 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01673488 Submitted on 28 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: Prey choice, competition and implications for extinction Hervé Bocherens a,*, Dorothée G. Drucker a,b, Dominique -

The Compositional Integrity of the Aurignacian

MUNIBE (Antropologia-Arkeologia) 57 Homenaje a Jesús Altuna 107-118 SAN SEBASTIAN 2005 ISSN 1132-2217 The Compositional Integrity of the Aurignacian La integridad composicional del Auriñaciense KEY WORDS: Aurignacian, lithic typology, lithic technology, organic technology, west Eurasia. PALABRAS CLAVE: Auriñaciense, tipología lítica, tecnología lítica, tecnología orgánica, Eurasia occidental. Geoffrey A. CLARK* Julien RIEL-SALVATORE* ABSTRACT For the Aurignacian to have heuristic validity, it must share a number of defining characteristics that co-occur systematically across space and time. To test its compositional integrity, we examine data from 52 levels identified as Aurignacian by their excavators. Classical indicators of the French Aurignacian are reviewed and used to contextualize data from other regions, allowing us to assess whether or not the Aurignacian can be considered a single, coherent archaeological entity. RESUMEN Para tener validez heurística, el Auriñaciense tiene que compartir características que co-ocurren sistemáticamente a través del espacio y tiempo. Para evaluar su integridad composicional, examinamos aquí los datos procedentes de 52 niveles identificados como ‘Auriñaciense’ por sus excavadores. Se repasan los indicadores ‘clásicos’ del Auriñaciense francés para contextualizar los datos procedentes de otras regio- nes con el objetivo de examinar si el Auriñaciense puede considerarse una sola coherente entidad arqueológica. LABURPENA Baliozkotasun heuristikoa izateko, Aurignac aldiak espazioan eta denboran zehar sistematikoki batera gertatzen diren ezaugarriak partekatu behar ditu. Haren osaketa osotasuna ebaluatzeko, beren hondeatzaileek ‘Aurignac aldikotzat” identifikaturiko 52 mailetatik ateratako datuak aztertzen ditugu hemen. Aurignac aldi frantziarraren adierazle “klasikoak” berrikusten dira beste hainbat eskualdetatik lorturiko datuak bere testuinguruan jartzeko Aurignac aldia entitate arkeologiko bakar eta koherentetzat jo daitekeen aztertzea helburu.