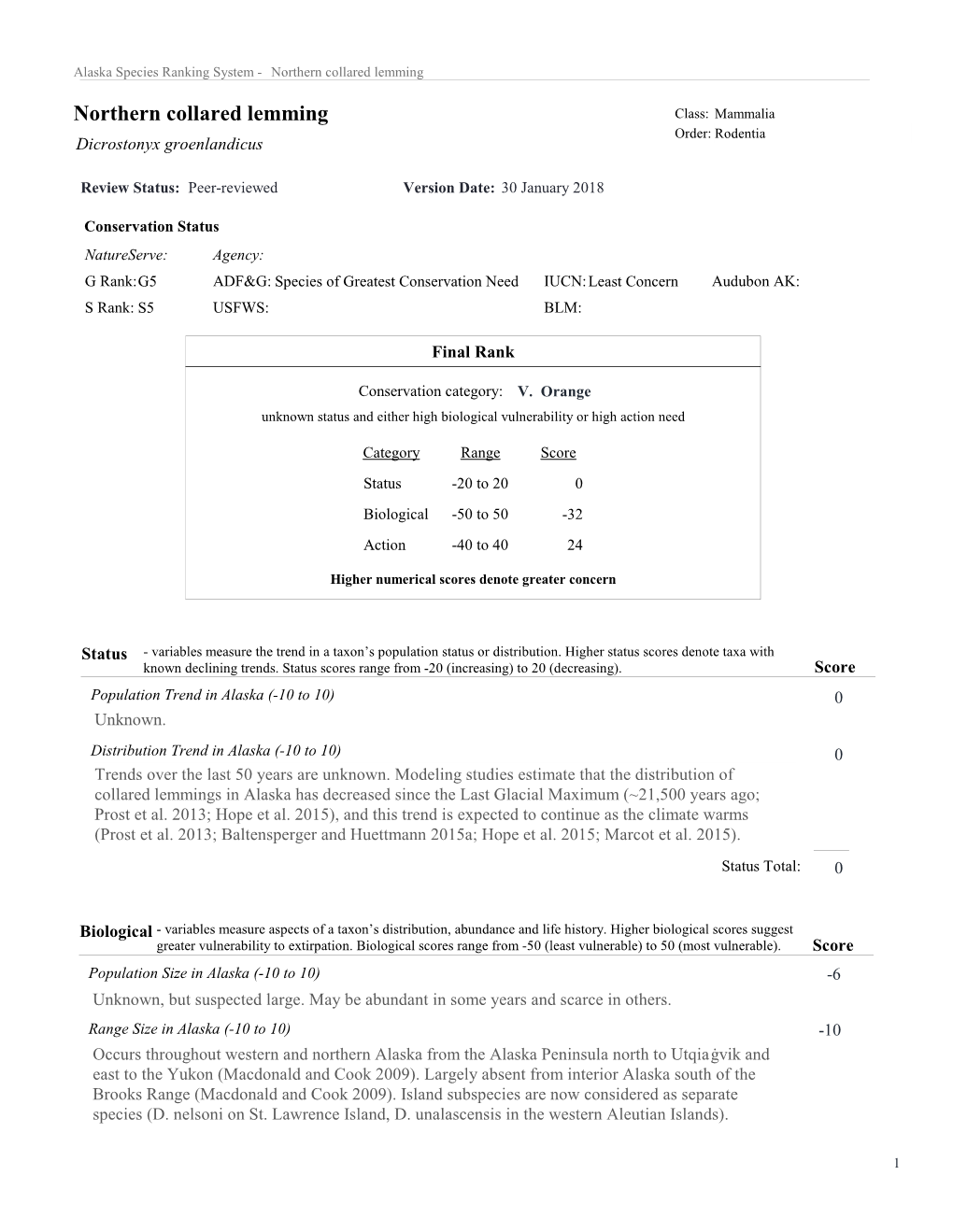

Northern Collared Lemming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legged Buzzards Cope with Changing Small Rodent Communities?

Received: 20 February 2019 | Revised: 26 July 2019 | Accepted: 2 August 2019 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14790 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Flexibility in a changing arctic food web: Can rough‐legged buzzards cope with changing small rodent communities? Ivan A. Fufachev1 | Dorothee Ehrich2 | Natalia A. Sokolova1,3 | Vasiliy A. Sokolov4 | Aleksandr A. Sokolov1,3 1Arctic Research Station of Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology, Ural Branch of Russian Abstract Academy of Sciences, Labytnangi, Russia Indirect effects of climate change are often mediated by trophic interactions and 2 Department of Arctic and Marine consequences for individual species depend on how they are tied into the local food Biology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway web. Here we show how the response of demographic rates of an arctic bird of prey 3Arctic Research Center of Yamal‐Nenets to fluctuations in small rodent abundance changed when small rodent community Autonomous District, Salekhard, Russia composition and dynamics changed, possibly under the effect of climate warming. 4Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology, Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, We observed the breeding biology of rough‐legged buzzards (Buteo lagopus) at the Ekaterinburg, Russia Erkuta Tundra Monitoring Site in southern Yamal, low arctic Russia, for 19 years Correspondence (1999–2017). At the same time, data on small rodent abundance were collected and Dorothee Ehrich, Department of Arctic and information on buzzard diet was obtained from pellet dissection. The small rodent Marine Biology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, 9037 Tromsø, Norway. community experienced a shift from high‐amplitude cycles to dampened fluctua‐ Email: [email protected] tions paralleled with a change in species composition toward less lemmings and more Funding information voles. -

Southern Bog Lemming, Synaptomys Cooperi,Andthe Mammals: Their Natural History, Classification, and Meadow Vole, Microtus Pennsylvanicus,Invirginia

Synaptomys cooperi (Baird, 1858) SBLE W. Mark Ford and Joshua Laerm CONTENT AND TAXONOMIC COMMENTS There are eight subspecies of the southern bog lem- ming (Synaptomys cooperi) recognized, four of which occur in the South: S. c. gossii, S. c. helaletes, S. c. kentucki, and S. c. stonei (Wetzel 1955, Barbour 1956, Hall 1981, Linzey 1983, Long 1987). However, Whitaker and Hamilton (1998) indicate that S. c. gossii, S. c. kentucki, and S. c. stonei could be referable to S. c. cooperi.The literature was reviewed by Linzey (1983). DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS The southern bog lemming is a robust, short-tailed vole with a broad head, small ears, and small eyes. Its measurements are: total length, 119–154 mm; tail, 13–25 mm; hind foot, 16–24 mm; ear, 8–14 mm; weight, 20–50 g. The dental formula for this species is: I 1/1, C 0/0, P 0/0, M 3/3 = 16 (Figure 1). The pel- age is bright chestnut to dark grizzled brown dor- sally, grading into silver grayish white ventrally, with gray to brown feet and tail. The southern bog lemming readily is distinguished from other voles by its short tail (usually less than hind foot length), pres- ence of a shallow longitudinal groove along upper incisors, and deep reentrant angles on molars. See keys for details. CONSERVATION STATUS The southern bog lemming has a global rank of Secure (NatureServe 2007). It is listed as Secure in Virginia and Apparently Secure in Kentucky and Tennessee. It is listed as Vulnerable in North Carolina, Imperiled in Arkansas, and Critically Imperiled in Georgia. -

Effectiveness of Lure in Capturing Northern Bog Lemmings on Trail Cameras Keely Benson [email protected]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers 2019 Effectiveness of Lure in Capturing Northern Bog Lemmings on Trail Cameras Keely Benson [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp Part of the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Keely, "Effectiveness of Lure in Capturing Northern Bog Lemmings on Trail Cameras" (2019). Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 248. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/248 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Effectiveness of Lure in Capturing Northern Bog Lemmings on Trail Cameras Keely Benson Wildlife Biology Program University of Montana Senior Thesis Project Graduating May 4, 2019 with a Bachelor of Science in Wildlife Biology Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of a Senior Honors Thesis WILD499/HONR499 Wildlife Biology Program The University of Montana Missoula, Montana Approved by: Committee Chair: Dr. Mark Hebblewhite, Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana Committee Members: Dr. Mike Mitchell, Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Montana Dr. Chad Bishop, Wildlife Biology Program University of Montana 1 Effectiveness of Lure in Capturing Northern Bog Lemmings on Trail Cameras Keely Benson Abstract Fens and bogs are unique wetlands that support a diversity of small mammals and many other rare species. -

Cycles and Synchrony in the Collared Lemming (Dicrostonyx Groenlandicus) in Arctic North America

Oecologia (2001) 126:216–224 DOI 10.1007/s004420000516 Martin Predavec · Charles J. Krebs · Kjell Danell Rob Hyndman Cycles and synchrony in the Collared Lemming (Dicrostonyx groenlandicus) in Arctic North America Received: 11 January 2000 / Accepted: 21 August 2000 / Published online: 19 October 2000 © Springer-Verlag 2000 Abstract Lemming populations are generally character- Introduction ised by their cyclic nature, yet empirical data to support this are lacking for most species, largely because of the Lemmings are generally known for their multiannual time and expense necessary to collect long-term popula- density fluctuations known as cycles. Occurring in a tion data. In this study we use the relative frequency of number of different species, these cycles are thought to yearly willow scarring by lemmings as an index of lem- have a fairly regular periodicity between 3 and 5 years, ming abundance, allowing us to plot population changes although the amplitude of the fluctuations can vary dra- over a 34-year period. Scars were collected from 18 sites matically. The collared lemming, Dicrostonyx groen- in Arctic North America separated by 2–1,647 km to in- landicus, is no exception, with earlier studies suggesting vestigate local synchrony among separate populations. that this species shows a strong cyclic nature in its popu- Over the period studied, populations at all 18 sites lation fluctuations (e.g. Chitty 1950; Shelford 1943). showed large fluctuations but there was no regular peri- However, later studies have shown separate populations odicity to the patterns of population change. Over all to be cyclic (Mallory et al. 1981; Pitelka and Batzli possible combinations of pairs of sites, only sites that 1993) or with little or no population fluctuations (Krebs were geographically connected and close (<6 km) et al. -

Investigating Evolutionary Processes Using Ancient and Historical DNA of Rodent Species

Investigating evolutionary processes using ancient and historical DNA of rodent species Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of London Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX Selina Brace November 2010 1 Declaration I, Selina Brace, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, it is always clearly stated. Selina Brace Ian Barnes 2 “Why should we look to the past? ……Because there is nowhere else to look.” James Burke 3 Abstract The Late Quaternary has been a period of significant change for terrestrial mammals, including episodes of extinction, population sub-division and colonisation. Studying this period provides a means to improve understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, and to determine processes that have led to current distributions. For large mammals, recent work has demonstrated the utility of ancient DNA in understanding demographic change and phylogenetic relationships, largely through well-preserved specimens from permafrost and deep cave deposits. In contrast, much less ancient DNA work has been conducted on small mammals. This project focuses on the development of ancient mitochondrial DNA datasets to explore the utility of rodent ancient DNA analysis. Two studies in Europe investigate population change over millennial timescales. Arctic collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) specimens are chronologically sampled from a single cave locality, Trou Al’Wesse (Belgian Ardennes). Two end Pleistocene population extinction-recolonisation events are identified and correspond temporally with - localised disappearance of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). A second study examines postglacial histories of European water voles (Arvicola), revealing two temporally distinct colonisation events in the UK. -

Collared Lemming 5/18/2005

NORTHERN COLLARED LEMMING and ALASKA SUBSPECIES Dicrostonyx groenlandicus Traill, 1823 (Muridae) Global rank G5 (22Jun2000) D. g. exsul G5T3 (14Mar2006) D. g. unalascensis G5T3 (26Apr2001) D. g. stevensoni G5T3 (14Mar2006) State rank S4 (14Mar2006) State rank reasons D. groenlandicus is widespread in western coastal Alaska throughout Aleutian Archipelago; insular populations restricted to St. Lawrence, Umnak, and Unalaska Islands. Suspected of a superspecies complex among North periodic high abundance although overall American Dicrostonyx (Rausch and Rausch abundance unknown; likely fluctuates, although 1972, Rausch 1977, also see Krohne 1982). trends in periodicity are difficult to determine. Former subspecies occurring in western Canada High summer predation and effects of climate and Alaska were recognized as separate species change on species’ habitat are potential threats. based mainly on karyotypes (Rausch and Rausch 1972, Rausch 1977, Krohne 1982, Honacki et al. Subspecies of concern ranked below: 1982, Baker et al. 2003). Musser and Carleton D. g. exsul: S3 (14Mar2006) (1993) noted, however, that although D. Insular taxa; state endemic with restricted groenlandicus, D. hudsonius, D. richardsoni, and range (St. Lawrence Island); current status D. unalascensis are morphologically distinct, the unknown; suspected periodic high distinctness of D. kilangmiutak, D. nelsoni, and D. abundance; population trend unknown. There rubricatus is more subtle and in need of further are no obvious threats at present. However, careful study. Jarrell and Fredga (1993) and due to its isolated and restricted habitat, this Engstrom (1999) suggest treating D. hudsonius, subspecies may be vulnerable to introduced D. richardsoni, and D. groenlandicus as full threats (e.g., rats). species (the latter including the other North American populations as subspecies). -

Sex Chromosome Translocations

RESEARCH ARTICLE Rapid Karyotype Evolution in Lasiopodomys Involved at Least Two Autosome ± Sex Chromosome Translocations Olga L. Gladkikh1☯, Svetlana A. Romanenko1,2☯*, Natalya A. Lemskaya1, Natalya A. Serdyukova1, Patricia C. M. O'Brien3, Julia M. Kovalskaya4, Antonina V. Smorkatcheva5, Feodor N. Golenishchev6, Polina L. Perelman1,2, Vladimir A. Trifonov1,2, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith3, Fengtang Yang7, Alexander S. Graphodatsky1,2 a11111 1 Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia, 2 Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Russia, 3 Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 4 Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia, 5 Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 6 Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 7 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] Citation: Gladkikh OL, Romanenko SA, Lemskaya NA, Serdyukova NA, O'Brien PCM, Kovalskaya JM, et al. (2016) Rapid Karyotype Evolution in Abstract Lasiopodomys Involved at Least Two Autosome ± Sex Chromosome Translocations. PLoS ONE 11 The generic status of Lasiopodomys and its division into subgenera Lasiopodomys (L. man- (12): e0167653. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0167653 darinus, L. brandtii) and Stenocranius (L. gregalis, L. raddei) are not generally accepted because of contradictions between the morphological and molecular data. To obtain cyto- Editor: Igor V. Sharakhov, Virginia Tech, UNITED STATES genetic evidence for the Lasiopodomys genus and its subgenera and to test the autosome to sex chromosome translocation hypothesis of sex chromosome complex origin in L. -

Lemmings One True Lemming, As Well As Several Closely Related Species Commonly Called Lemmings, Lives in Alaska

Lemmings One true lemming, as well as several closely related species commonly called lemmings, lives in Alaska. Distinguishing one from the other, or even lemmings from voles, is difficult. Many of the small rodents in the north have a similar appearance, especially during the summer months. The information below will help to identify lemming species in the field, but positive identification can be made only with the help of a mammalogy expert, text or field guide which gives detailed information on tooth structure and skull conformation. The brown lemming, Lemmus trimucronatus, is the only true lemming in Alaska. Brown lemmings inhabit open tundra areas throughout Siberia and North America. They live in northern treeless regions, usually in low-lying, flat meadow habitats dominated by sedges, grasses and mosses. Their principal summer foods are tender shoots of grasses and sedges. During the winter they eat frozen, but still green, plant material, moss shoots, and the bark and twigs of willow and dwarf birch. There is some evidence that brown lemmings are cannibalistic when food is scarce. True lemmings, the largest of the various lemming species, range from 4 to 5½ inches (100 to 135 mm) in length, including a 1 inch (12 to 26mm) tail. Adults weigh from just over an ounce to 4 ounces (40 to 112 g) but average 2¾ ounces (78 g). These lemmings are heavily furred, grayish or brownish above and buffy beneath, and are stockily built. They are well-adapted for their rigorous climate with short tails and ears so small they are almost hidden by fur. -

Ancient DNA Supports Southern Survival of Richardsons Collared Lemming (Dicrostonyx Richardsoni) During the Last Glacial Maximum

Molecular Ecology (2013) 22, 2540–2548 doi: 10.1111/mec.12267 Ancient DNA supports southern survival of Richardson’s collared lemming (Dicrostonyx richardsoni) during the last glacial maximum TARA L. FULTON,*1 RYAN W. NORRIS,*2 RUSSELL W. GRAHAM,† HOLMES A. SEMKEN JR‡ and BETH SHAPIRO*1 *Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, †Department of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, ‡Department of Geoscience, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA Abstract Collared lemmings (genus Dicrostonyx) are circumpolar Arctic arvicoline rodents asso- ciated with tundra. However, during the last glacial maximum (LGM), Dicrostonyx lived along the southern ice margin of the Laurentide ice sheet in communities com- prising both temperate and boreal species. To better understand these communities and the fate of these southern individuals, we compare mitochondrial cytochrome b sequence data from three LGM-age Dicrostonyx fossils from south of the Laurentide ice sheet to sequences from modern Dicrostonyx sampled from across their present-day range. We test whether the Dicrostonyx populations from LGM-age continental USA became extinct at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition ~11000 years ago or, alterna- tively, if they belong to an extant species whose habitat preferences can be used to infer the palaeoclimate along the glacial margin. Our results indicate that LGM-age Dicrostonyx from Iowa and South Dakota belong to Dicrostonyx richardsoni, which currently lives in a temperate tundra environment west of Hudson Bay, Canada. This suggests a palaeoclimate south of the Laurentide ice sheet that contains elements simi- lar to the more temperate shrub tundra characteristic of extant D. -

Complete Mitochondrial Genome of an Arctic Collared Lemming Subspecies Endemic to the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago, Russia

Ecologica Montenegrina 40: 133-139 (2021) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em http://dx.doi.org/10.37828/em.2021.40.12 Complete mitochondrial genome of an Arctic Collared Lemming subspecies endemic to the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago, Russia VITALY M. SPITSYN1,*, ALEXANDER V. KONDAKOV1,2,3, ELSA FROUFE4, MIKHAIL Y. GOFAROV1, ANDRÉ GOMES-DOS-SANTOS4,5, JOÃO TEIGA-TEIXEIRA4, ELIZAVETA A. SPITSYNA1, NATALIA A. ZUBRII1,3, MANUEL LOPES-LIMA4,6 & IVAN N. BOLOTOV1,2,3 1N. Laverov Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Arkhangelsk, Russia 2Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia 3Northern Arctic Federal University, Arkhangelsk, Russia 4CIIMAR/CIMAR – Interdisciplinary Centre of Marine and Environmental Research, University of Porto, Matosinhos, Portugal 5Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, Porto, Portugal 6CIBIO/InBIO – Research Center in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, University of Porto, Vairão, Portugal *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 17 March 2021│ Accepted by V. Pešić: 20 March 2021 │ Published online: 22 March 2021. In this study, we present an announcement of Novaya Zemlya Collared Lemming Dicrostonyx torquatus ungulatus (von Baer, 1841) complete mitogenome. This rodent was described historically as an Arctic Collared Lemming subspecies endemic to Novaya Zemlya (Arctic Russia) but its taxonomic status was unclear due to the lack of available molecular data. Based on a comprehensive mitogenomic phylogeny of the Arctic Collared Lemming, we show that this insular population shares a highly divergent mtDNA sequence (total length 16,341 bp). Hence, it should be considered a valid subspecies of the Arctic Collared Lemming. -

Phylogeography of a Holarctic Rodent (Myodes Rutilus): Testing High

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2014) ORIGINAL Phylogeography of a Holarctic rodent ARTICLE (Myodes rutilus): testing high-latitude biogeographical hypotheses and the dynamics of range shifts Brooks A. Kohli1,2*, Vadim B. Fedorov3, Eric Waltari4 and Joseph A. Cook1 1Department of Biology and Museum of ABSTRACT Southwestern Biology, University of New Aim We used the Holarctic northern red-backed vole (Myodes rutilus)asa Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-1051, USA, 2 model organism to improve our understanding of how dynamic, northern Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, high-latitude environments have affected the genetic diversity, demography and Durham, NH 03824-3534, USA, 3Institute of distribution of boreal organisms. We tested spatial and temporal hypotheses Arctic Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, derived from previous mitochondrial studies, comparative phylogeography, pal- Fairbanks, AK 99775-7000, USA, 4Department aeoecology and the fossil record regarding diversification of M. rutilus in the of Biology, City College of New York, Palaearctic and Beringia. New York, NY 10031, USA Location High-latitude biomes across the Holarctic. Methods We used a multilocus phylogeographical approach combined with species distribution models to characterize the biogeographical and demo- graphic history of M. rutilus. Our molecular assessment included widespread sampling (more than 100 localities), species tree reconstruction and population genetic analyses. Results Three well-differentiated mitochondrial lineages correspond to geo- graphical regions, but nuclear genes were less structured. Multilocus divergence estimates indicated that diversification of M. rutilus was driven by events occurring before c. 100 ka. Population expansion in all three clades occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and presumably led to secondary contact. -

Preliminary Analysis of European Small Mammal Faunas of the Eemian Interglacial: Species Composition and Species Diversity at a Regional Scale

Article Preliminary Analysis of European Small Mammal Faunas of the Eemian Interglacial: Species Composition and Species Diversity at a Regional Scale Anastasia Markova * and Andrey Puzachenko Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Staromonetny 29, Moscow 119017, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-495-959-0016 Academic Editors: Maria Rita Palombo and Valentí Rull Received: 22 May 2018; Accepted: 20 July 2018; Published: 26 July 2018 Abstract: Small mammal remains obtained from the European localities dated to the Eemian (Mikulino) age have been analyzed for the first time at a regional scale based on the present biogeographical regionalization of Europe. The regional faunas dated to the warm interval in the first part of the Late Pleistocene display notable differences in fauna composition, species richness, and diversity indices. The classification of regional faunal assemblages revealed distinctive features of small mammal faunas in Eastern and Western Europe during the Eemian (=Mikulino, =Ipswichian) Interglacial. Faunas of the Iberian Peninsula, Apennine Peninsula, and Sardinia Island appear to deviate from the other regions. In the Eemian Interglacial, the maximum species richness of small mammals (≥40 species) with a relatively high proportion of typical forest species was recorded in Western and Central Europe and in the western part of Eastern Europe. The lowest species richness (5–14 species) was typical of island faunas and of those in the north of Eastern Europe. The data obtained make it possible to reconstruct the distribution of forest biotopes and open habitats (forest-steppe and steppe) in various regions of Europe. Noteworthy is a limited area of forests in the south and in the northeastern part of Europe.