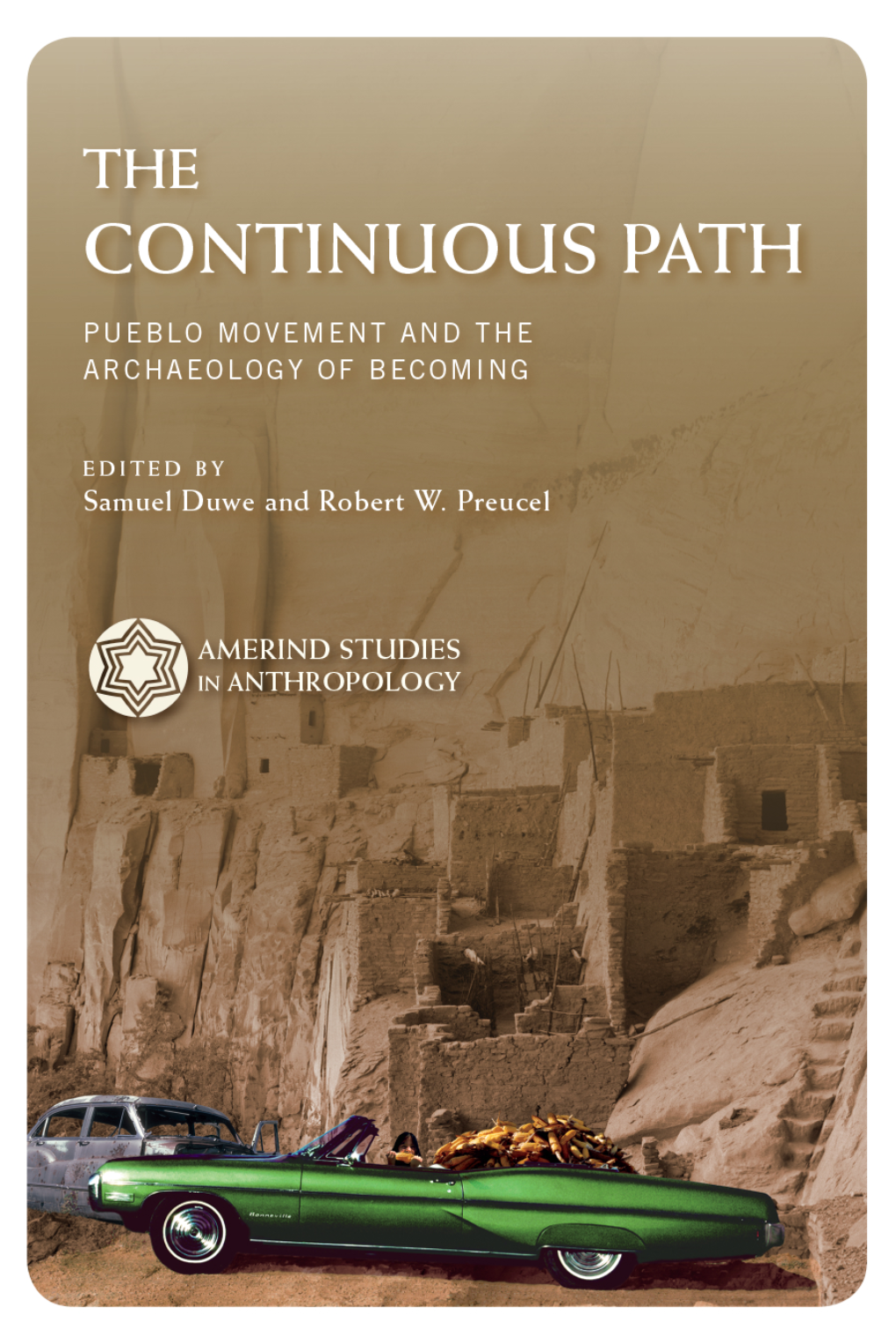

The Continuous Path: Pueblo Movement and the Archaeology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Worksheet (Grades 6–8)

Name ______________________ Pueblo Indian History for Kids Student Worksheet (Grades 6–8) Overview Pueblo Indian History for Kids is an online timeline that tells the history of the Pueblo Indian people of the American Southwest. The timeline covers more than 15,000 years of history! Use this worksheet to guide your exploration of the timeline. As you move through the timeline, answer the questions below. Keep a list of questions you have as you explore. Go to: www.crowcanyon.org/pueblohistorykids Introduction 1. Who are the Pueblo Indians? 2. What other names are used to describe this group of people? 3. Where is the Mesa Verde region? 4. What does “Mesa Verde” mean, and what is the region’s environment like? 5. How is the environment of the Mesa Verde region similar to the environment where you live? How is it different? 6. What are two ways we can learn about Pueblo history? Can you think of others? 1 Pueblo Indian History for Kids―Student Worksheet (6–8) Paleoindian 1. What does the term “hunter-gatherer” mean? 2. How would you describe how people in your culture acquire food? Where do you get your food? 3. Identify two similarities and two differences between your life and that of Paleoindian people. Archaic 1. There were several major differences between the Paleoindian and Archaic periods. What were they and what is the evidence for these differences? 2. What important tools were used during the Archaic period? How did they change ways of life for people in the Mesa Verde region? 3. Why do you think there is not as much evidence for how people lived during the Paleoindian and Archaic periods as there is for later time periods? 2 Pueblo Indian History for Kids―Student Worksheet (6–8) Basketmaker 1. -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N

MS-372 The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N. Fort Valley Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001 (928)774-5211 ext. 256 Title Harold Widdison Rock Art collection Dates 1946-2012, predominant 1983-2012 Extent 23,390 35mm color slides, 6,085 color prints, 24 35mm color negatives, 1.6 linear feet textual, 1 DVD, 4 digital files Name of Creator(s) Widdison, Harold A. Biographical History Harold Atwood Widdison was born in Salt Lake City, Utah on September 10, 1935 to Harold Edward and Margaret Lavona (née Atwood) Widdison. His only sibling, sister Joan Lavona, was born in 1940. The family moved to Helena, Montana when Widdison was 12, where he graduated from high school in 1953. He then served a two year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1956 Widdison entered Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, graduating with a BS in sociology in 1959 and an MS in business in 1961. He was employed by the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington DC before returning to graduate school, earning his PhD in medical sociology and statistics from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio in 1970. Dr. Widdison was a faculty member in the Sociology Department at Northern Arizona University from 1972 until his retirement in 2003. His research foci included research methods, medical sociology, complex organization, and death and dying. His interest in the latter led him to develop one of the first courses on death, grief, and bereavement, and helped establish such courses in the field on a national scale. -

Statement by Author

Maya Wetlands: Ecology and Pre-Hispanic Utilization of Wetlands in Northwestern Belize Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Baker, Jeffrey Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 10:39:16 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/237812 MAYA WETLANDS ECOLOGY AND PRE-HISPANIC UTILIZATION OF WETLANDS IN NORTHWESTERN BELIZE by Jeffrey Lee Baker _______________________ Copyright © Jeffrey Lee Baker 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Anthropology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2 0 0 3 2 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This endeavor would not have been possible with the assistance and advice of a number of individuals. My committee members, Pat Culbert, John Olsen and Owen Davis, who took the time to read and comment on this work Vernon Scarborough and Tom Guderjan also commented on this dissertation and provided additional support during the work. Vernon Scarborough invited me to northwestern Belize to assist in his work examining water management practices at La Milpa. An offer that ultimately led to the current dissertation. Without Tom Guderjan’s offer to work at Blue Creek in 1996, it is unlikely that I would ever have completed my dissertation, and it is possible that I might no longer be in archaeology, a decision I would have deeply regretted. -

Pueblo Indian History for Kids Student Worksheet (Grades 4–6)

Name ______________________ Pueblo Indian History for Kids Student Worksheet (Grades 4–6) Overview Pueblo Indian History for Kids is an online timeline that tells the history of the Pueblo Indian people of the American Southwest. The timeline covers more than 15,000 years of history! Use this worksheet to guide your exploration of the timeline. As you move through the timeline, answer the questions below. Keep a list of questions you have as you explore. Go to: www.crowcanyon.org/pueblohistorykids Introduction 1. Who are the Pueblo Indians? 2. What other names are used to describe this group of people? 3. Where is the Mesa Verde region? What is the environment like there? 4. How is the environment of the Mesa Verde region similar to the environment where you live? How is it different? 5. What are some of the different ways we can learn about the Pueblo past? 1 Pueblo Indian History for Kids―Student Worksheet (4–6) Paleoindian 1. What does the term “hunter-gatherer” mean? 2. How do you get your food? Where does it come from? Archaic 1. How is the Archaic period different than the Paleoindian period? 2. What two important tools were used during the Archaic time period? How were they used? Basketmaker 1. What made the Basketmaker time period different than the Archaic period? 2. Describe the diet of the Pueblo people during the Basketmaker time period. 3. What important structures were used during the Basketmaker period? How were they used? What structures do people use today with similar purposes? 2 Pueblo Indian History for Kids―Student Worksheet (4–6) Pueblo I 1. -

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona Eric Menasco NPS Terry Reiners Arizona is the astrotourism capital of the United States. Its diverse landscape—from the Grand Canyon and ponderosa forests in the north to the Sonoran Desert and “sky islands” in the south—is home to more certified Dark Sky Places than any other U.S. state. In fact, no country outside the U.S. can rival Arizona’s 16 dark-sky communities and parks. Arizona helped birth the dark-sky preservation movement when, in 2001, the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) designated Flagstaff as the world’s very first Dark Sky Place for the city’s commitment to protecting its stargazing- friendly night skies. Since then, six other Arizona communities—Sedona, Big Park, Camp Verde, Thunder Mountain Pootseev Nightsky and Fountain Hills—have earned Dark Sky status from the IDA. Arizona also boasts nine Dark Sky Parks, defined by the IDA as lands with “exceptional quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.” The most famous of these is Grand Canyon National Park, where remarkably beautiful night skies lend draw-dropping credence to the Park Service’s reminder that “half the park is after dark Of the 16 Certified IDA International Dark Sky Communities in the US, 6 are in Arizona. These include: • Big Park/Village of Oak Creek, Arizona • Camp Verde, Arizona • Flagstaff, Arizona • Fountain Hills, Arizona • Sedona, Arizona • Thunder Mountain Pootsee Nightsky- Kaibab Paiute Reservation, Arizona Arizona Office of Tourism—Dark Skies Page 1 Facebook: @arizonatravel Instagram: @visit_arizona Twitter: @ArizonaTourism #VisitArizona Arizona is also home to 10 Certified IDA Dark Sky Parks, including: Northern Arizona: Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Offering multiple hiking trails around this former volcanic cinder cone, visitors can join rangers on tours to learn about geology, wildlife, and lava flows. -

Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: a Biographical and Contextual View Karen L

Andean Past Volume 7 Article 14 2005 Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View Karen L. Mohr Chavez deceased Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mohr Chavez, Karen L. (2005) "Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View," Andean Past: Vol. 7 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFRED KIDDER II IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CONTEXTUAL VIEW KAREN L. MOHR CHÁVEZ late of Central Michigan University (died August 25, 2001) Dedicated with love to my parents, Clifford F. L. Mohr and Grace R. Mohr, and to my mother-in-law, Martha Farfán de Chávez, and to the memory of my father-in-law, Manuel Chávez Ballón. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SERGIO J. CHÁVEZ1 corroborate crucial information with Karen’s notes and Kidder’s archive. Karen’s initial motivation to write this biography stemmed from the fact that she was one of Alfred INTRODUCTION Kidder II’s closest students at the University of Pennsylvania. He served as her main M.A. thesis This article is a biography of archaeologist Alfred and Ph.D. dissertation advisor and provided all Kidder II (1911-1984; Figure 1), a prominent necessary assistance, support, and guidance. -

Pueblo III Towers in the Northern San Juan. Kiva 75(3)

CONNECTING WORLDS: PUEBLO III TOWERS IN THE NORTHERN SAN JUAN Ruth M. Van Dyke and Anthony G. King ABSTRACT The towers of the northern San Juan, including those on Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, and Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, were constructed on mesa tops, in cliff dwellings, along canyon rims, and in canyon bottoms during the Pueblo III period (A.D. 1150–1300)—a time of social and environmental upheaval. Archaeologists have interpreted the towers as defensive strongholds, lookouts, sig- naling stations, astronomical observatories, storehouses, and ceremonial facilities. Explanations that relate to towers’ visibility are most convincing. As highly visible, public buildings, towers had abstract, symbolic meanings as well as concrete, func- tional uses. We ask not just, “What were towers for?” but “What did towers mean?” One possibility is that towers were meant to encourage social cohesiveness by invoking an imagined, shared Chacoan past. The towers reference some of the same ideas found in Chacoan monumental buildings, including McElmo-style masonry, the concept of verticality, and intervisibility with iconic landforms. Another possibility is that towers symbolized a conduit out of the social and envi- ronmental turmoil of the Pueblo III period and into a higher level of the layered universe. We base this interpretation on two lines of evidence. Pueblo oral tradi- tions provide precedent for climbing upwards to higher layers of the world to escape hard times. Towers are always associated with kivas, water, subterranean concavities, or earlier sites—all places that, in Pueblo cosmologies, open to the world below our current plane. RESUMEN Las torres del norte del San Juan, inclusive ésos en Mesa Verde, en Hovenweep, y en el monumento nacional de Canyons of the Ancients, fueron construidos en cimas de mesa, en casas en acantilado, por los bordes de cañones, y en fondos de cañones durante Pueblo III (dC. -

Arizona, Road Trips Are As Much About the Journey As They Are the Destination

Travel options that enable social distancing are more popular than ever. We’ve designated 2021 as the Year of the Road Trip so those who are ready to travel can start planning. In Arizona, road trips are as much about the journey as they are the destination. No matter where you go, you’re sure to spy sprawling expanses of nature and stunning panoramic views. We’re looking forward to sharing great itineraries that cover the whole state. From small-town streets to the unique landscapes of our parks, these road trips are designed with Grand Canyon National Park socially-distanced fun in mind. For visitor guidance due to COVID19 such as mask-wearing, a list of tourism-related re- openings or closures, and a link to public health guidelines, click here: https://www.visitarizona. com/covid-19/. Some attractions are open year-round and some are open seasonally or move to seasonal hours. To ensure the places you want to see are open on your travel dates, please check their website for hours of operation. Prickly Pear Cactus ARIZONA RESOURCES We provide complete travel information about destinations in Arizona. We offer our official state traveler’s guide, maps, images, familiarization trip assistance, itinerary suggestions and planning assistance along with lists of tour guides plus connections to ARIZONA lodging properties and other information at traveltrade.visitarizona.com Horseshoe Bend ARIZONA OFFICE OF TOURISM 100 N. 7th Ave., Suite 400, Phoenix, AZ 85007 | www.visitarizona.com Jessica Mitchell, Senior Travel Industry Marketing Manager | T: 602-364-4157 | E: [email protected] TRANSPORTATION From east to west both Interstate 40 and Interstate 10 cross the state. -

Information to Users

Great kivas as integrative architecture in the Silver Creek community, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herr, Sarah Alice, 1970- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 15:30:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278407 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, soms thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

OTM-Newsletter-2020-05

Spring/Summer 2020 Volume 10, Issue 1 Old Trails Journal The newsletter for supporters of the Old Trails Museum/Winslow Historical Society *POSTPONED* OTM Responds to COVID-19 Like many businesses and organizations in Winslow and around the world, the Old OTM 2020 Trails Museum is closed until further notice. The Board and staff are working on Spring History reopening plans, and we will notify the public of the date as soon as we have one. Highlight In the meantime, we hope to stay connected with our supporters online. We’re posting “OTM Calendar Highlights” each Monday on the OTM Facebook page until Sativa we reopen. The series features a chronological image and caption from our historical calendar archives, and it also previews our 2021 calendar, Winslow Through the Peterson’s Decades. Next year’s edition will feature images from each decade of Winslow’s workshop on history that have never been published in an OTM calendar or our Winslow book. researching We also invite you to go to the “Exhibits” page on the OTM Website and explore historic these diverse topics from Winslow’s rich history: newspapers, • Journeys to Winslow (2017) • The Winslow Visitors Center: A Hubbell Trading Post History (2017) originally • African Americans in Winslow: Scenes from Our History (2017) • Snowdrift Art Space: One Hundred Years of History (2014) scheduled for • Flying through History: The Winslow-Lindbergh Regional Airport (2014) March 28 at the • The Women of Winslow (2011) Winslow Visitors The Board, staff, and volunteers of the Winslow Historical Society and Old Trails Center, Museum wish you and yours good health, and we hope to see you in person in the near future.