Montezuma Castle and Montezuma Well

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Traveller

Travel is more than just A to B. Travel should take you to a warmer destination. Getting warmer has never been this much fun! With close to 300 days of sunshine per year, Pointe Hilton Squaw Peak Resort and Pointe Hilton Tapatio Cliffs Resort can turn any day into a splashing good time. With all-suite accommodations, award-winning spa services, a challenging 18-hole championship golf course, acres of shimmering pools and great rates, the Pointe Hilton Resorts can make your vacation dreams a reality. For special offers and reservations, contact us today at 1-800-943-7752, 1-800-HILTONS or visit us online at pointehilton.com Phoenix, Arizona 602-943-7752 pointehilton.com Travel should take you placesTM Hilton HHonors® membership, earning of Points & Miles,® and redemption of points are subject to HHonors Terms and Conditions. ©2007 Hilton Hospitality, Inc. Table of Contents Phoenix & Central Arizona 8 A wonderful balance of big- city glamour and wide-open desert spaces Tucson & Southern Arizona 24 Spanish history, western mystery and majestic desert scenery Northern Arizona 30 The “Mother Road”, Monument Valley, and of course, the Grand Canyon North Central Arizona 36 Cool, pine-scented forests, ghost towns and haunting ruins Arizona’s West Coast 40 The mighty Colorado River, London Bridge and desert wildlife How To Sell Arizona 44 Industry expert Steve Crowhurst’s tips on selling the Grand Canyon State ARIZONA – A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT TO THE SEPTEMBER 2007 ISSUE OF CANADIAN TRAVELLER Published 12 times a year by 1104 Hornby Street,Suite 203 Vancouver,British Columbia Canada V6Z 1V8 THE DESTINATION SALES RESOURCE FOR TRAVEL PROFESSIONALS Contents © 2007 by ACT Communications Inc. -

Arizona Historic Preservation Plan 2000

ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONASTATEPARKSBOARD Chair Executive Staff Walter D. Armer, Jr. Kenneth E. Travous Benson Executive Director Members Renée E. Bahl Suzanne Pfister Assistant Director Phoenix Jay Ream Joseph H. Holmwood Assistant Director Mesa Mark Siegwarth John U. Hays Assistant Director Yarnell Jay Ziemann Sheri Graham Assistant Director Sedona Vernon Roudebush Safford Michael E. Anable State Land Commissioner ARIZONA Historic Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 StateHistoricPreservationOffice PartnershipsDivision ARIZONASTATEPARKS 5 6 StateHistoricPreservationOffice 3 4 PartnershipsDivision 7 ARIZONASTATEPARKS 1300WestWashington 8 Phoenix,Arizona85007 1 Tel/TTY:602-542-4174 2 http://www.pr.state.az.us ThisPlanUpdatewasapprovedbythe 9 11 ArizonaStateParksBoardonMarch15,2001 Photographsthroughoutthis 10 planfeatureviewsofhistoric propertiesfoundwithinArizona 6.HomoloviRuins StateParksincluding: StatePark 1.YumaCrossing 7.TontoNaturalBridge9 StateHistoricPark StatePark 2.YumaTerritorialPrison 8.McFarland StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark 3.Jerome 9.TubacPresidio StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark Coverphotographslefttoright: 4.FortVerde 10.SanRafaelRanch StateHistoricPark StatePark FortVerdeStateHistoricPark TubacPresidioStateHistoricPark 5.RiordanMansion 11.TombstoneCourthouse McFarlandStateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark YumaTerritorialPrisonStateHistoricPark RiordanMansionStateHistoricPark Tombstone Courthouse Contents Introduction 1 Arizona’s -

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

Abandon Grasshopper 107

Welch - The Last Archaeologist to (Almost) Abandon Grasshopper 107 The Last Archaeologist to (Almost) Abandon Grasshopper John R. Welch, Ph.D., University of Arizona, Professor Jointly Appointed in the Department of Archaeology and the School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University The history of Arizona Anthro- and canyons of White Mountain pology engagements with Apach- Apache lands and found myself es and their territory perpetuates lingering well into August. In ad- my occupation of and with Grass- dition to the region’s rugged ro- hopper and other sites excavated mantic allure and understudied by my forebears and benefactors. Apache archaeology, my Grass- Arizona Anthropology’s centen- hopper Region infatuation led not nial offers occasions to both cele- only to four more seasons with the brate and reflect upon the sources field school, but also to employ- and consequences of individual ment as a Bureau of Indian Affairs and institutional successes. My contractor (1987–1992), then staff intention here is to direct atten- archaeologist (1992–2005), then tion to contributions made to Ar- as the Tribe’s historic preserva- izona Anthropology by the White tion officer (THPO, 1996–2005) Mountain Apache Tribe and vice (Welch in Nicholas et al. 2008). versa. The history of the relation- Not even a mid-career vault from ship and the directions taken by the government jobs in Arizona to Si- Tribe in response to the relationship mon Fraser University loosened provide the basis for my opinion the ties that bind me to the Tribe that Arizona Anthropology should and its lands: I serve as an advisor abandon neither Grasshopper nor to the Tribe’s Heritage Program the Tribe more generally. -

Fact Sheet Overview

southwestlearning.org MONTEZUMA WELL Montezuma Well FACTOVERVIEW SHEET CO 1864 - Present W AN (2012:FIGURE 7) Montezuma Well, long the home of prehistoric Hohokam, Sinagua, Yavapai, and Apache people, was, following the establishment of Arizona Territory in 1863, a working cattle ranch and one of Arizona’s first tourist attractions before be- ing acquired by the National Park Service in 1947. The Well itself passed through a series of owners between 1883 and 1888, when William and Margorie Back bought the squat- ters claim for the land and filed for a homestead. Over the next 60 years, two generations of the Back family operated the Well ranch and museum. History of Land Use Although most likely encountered by Spanish explorers in the William “Bill” Beriman Back sitting on the porch of the original Back Fam- late 1500s, Montezuma Well was not officially re-discovered ily home. Original image courtesy of Helen Cain. until 1864, when it acquired the name “Montezuma” from a party venturing forth from Fort Whipple, a military establish- diverting water from both Wet Beaver Creek and Montezuma ment some 50 miles west. These early visitors noted not only Well to irrigate 30 acres of their holdings, which they oper- the deep water of the Well itself, but also the prehistoric dwell- ated as a mail station and support post supplying hay and veg- ings in and around the Well, and the prehistoric irrigation ditch etables to the local military post and feed and range space for later reclaimed and used by the first settlers (this ditch trans- the horses and mules of the express riders, freight wagons, and ports Well water to residents of the Verde Valley to this day). -

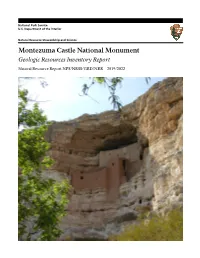

Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2019/2022 ON THE COVER Photograph of Montezuma Castle (cliff dwellings). Early in the 12th century, ancestral Native American people called the “Southern Sinagua” by archeologists began building a five-story, 20-room dwelling in an alcove about 30 m (100 ft) above the valley floor. The alcove occurs in the Verde Formation, limestone. The contrast of two colors of mortar is evident in this photograph. More than 700 years ago, inhabitants applied the lighter white mortar on the top one-third. In the late 1990s, the National Park Service applied the darker red mortar on the bottom two-thirds. Photograph by Katie KellerLynn (Colorado State University). THIS PAGE Photograph of Montezuma Castle National Monument. View is looking west from the top of the Montezuma Castle ruins. Beaver Creek, which flows through the Castle Unit of the monument, is on the valley floor. NPS photograph available at https://www.nps.gov/moca/learn/photosmultimedia/ photogallery.htm (accessed 22 November 2017). Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2019/2022 Katie KellerLynn Colorado State University Research Associate National Park Service Geologic Resources Inventory Geologic Resources Division PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 October 2019 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. -

Foundation Document Overview, Montezuma Castle National

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Montezuma Castle National Monument Arizona Contact Information For more information about the Montezuma Castle National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 928-567-5276 or write to: Superintendent, Montezuma Castle National Monument, PO Box 219 Camp Verde, AZ 86322 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Montezuma Castle National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • Montezuma Castle is an iconic and well-preserved Sinaguan cliff dwelling. The castle is the most visible feature of a larger community found within a diverse natural landscape in the Verde Valley of Arizona. • The archeological features at Montezuma Castle National The purpose of MONTEZUMA CASTLE Monument represent a continuum of land use from NATIONAL MONUMENT is to protect, prehistoric cultures through the present and offer enormous study, and interpret the outstanding learning potential about human adaptation to a harsh prehistoric and historic cultural features desert environment. and natural ecosystems including iconic cliff dwellings, artesian-fed sinkhole, • Montezuma Well is an artesian spring within a limestone and desert riparian environment. sink containing substantial scientific value, endemic species, and a natural outlet connected to remnants of an extensive prehistoric and historic irrigation system. -

Brief Descriptions of the Historical and Cultural Background of the Navajo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 028 872 RC 003 368 Indians of Arizona. Bureau of Indian Affairs (Dept. of Interior), Washington, D.C. Pub Date 68 Note-28p. Available from-Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (0-292-749, S0.15). EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-*American Indian% *Cultural Background, Cultural Differences, Cultural Environment, *Economic Development, Economic Progress, *Educational Opportunities, Employment Opportunities, Ethnic Groups, Health Program% *United States History Identifiers-Apache% *Arizona, Hopis, Navajos, Papago% Pima% Yumas Brief descriptions of the historical and cultural background of the Navajo. Apache, Hopi, Pima, Papago, Yuma, Maricopa, Mohave, Cocopah, Havasupai, Hualapai. Yavapai, and Paiute Indian tribes of Arizona are presented. Further information is given concerning the educational, housing, employment, and economic development taking place on the reservations in Arizona today. A list of places of interest is included. (DK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION 8, WELFARE NDIANS OF OFFICE OF EDUCATION /ANIL THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. Alp - 11101.. 1. t Ask y: _ a A 1.0 r tio 4: '717' :V! -,r44 AMP= alMa. !, el"' 4. iiiityl.IP , :; t,,:;- Ago\ -;4- - ' 1 ,_#,;,,ii,414, ,.. 7 t-, ..: -1,.. A p- ' z I ',; t*, ''''-',"2k;;L. , . ANA, ., 47' :. 1 -,. ,k.,\ '4'-';:.,-%'41i,'' ';' l'V i":, \ \ I r --.116116'1%.4, ,ri 4 * N. - ; !'''' A' \ \ .. .....--- . 0,,...".4 _.......la' 4,-, '', \ Crf71' . *'.* , .01 Sired by the muddy Colorado, C thegreatbluelakecalled Powell lies behind Glen Canyon CV, - ik:-.E", I 'Xga , Dam and crosses the Arizona- JAME6.1:". -

Approved: the DIFFUSION of SHELL ORNAMENTS in THE

The diffusion of shell ornaments in the prehistoric Southwest Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors McFarland, Will-Lola Humphries, 1900- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 05:59:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553574 THE DIFFUSION OF SHELL ORNAMENTS IN THE PREHISTORIC SOUTH-FEST by V/ill-Lola McFarland A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts' in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1 9 4 1 Approved: I - 2- C--V/ Director of Thesis ~ Date 4 '-V- - *- l. ACKKO mLKIXjj IrJTT I wish to expro: s appreciation to my cat Liable advioar, Mrs. Clara Lee Tanner, for her inspiration and untiring effort in assisting mo with the preparation of this thesis. I also wish to thank Dr. iSwil ... Haury, head of the Anthropology Department, and Dr. 3d ward W. jplccr for giving nu the benefit of their exper ience in their very helpful guidance and suggestions. ;,.L HOF. 1 3 < t b b l TABLE OF CONTENTS CflAPT^£R : . • . ' PACE 32ITRODUCTIOH................... ........... i I. STATUS OF SOXJTHV/NSTCULTURE.. ^ • 1 Gopgraphleal Distribution and General Outline........ .................... 1 Ilohokaa............................. 3 Anasazl............................. 9 Mogollon.......... .................. 16 II. SHELL TYPES AI!D THE EORKINa OF SHELL. -

1 Artist in Residence Program

Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well & Tuzigoot National Park Service National Monuments US Department of the Interior Verde Valley, Arizona ARTIST IN RESIDENCE PROGRAM Montezuma Castle, Montezume Well & Tuzigoot National Park Service National Monument US Department of the Interior Verde Valley, Arizona Artist in Residence Program •NPS invites artists to participate in our Arts in the Park, Artist in Residence program; •Artists have impacted the formation, expansion, and direction of our national parks; •Artists provide a window into the American landscape to people that may never visit these awesome places, creating connections through photography and paintings; •Today, artists use a wide variety of media to draw inspiration from park lands, Montezuma Castle and Tuzigoot National Monuments’ AiR Program continues the tradition of arts in the parks. Founded in 2018, the program brings artists to the park to share their inspirations, ideas and artwork with the visiting public. •The AiR program offers artists the opportunity to pursue their discipline while immersed in the park landscape. Selected artists live in park housing and are provided a modest stipend to assist with travel and food expenses. 1 Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, & Tuzigoot National Park Service National Monuments US Department of the Interior Verde Valley, Arizona Housing: Artists are provided a fully furnished 1 bedroom manufactured home, located at Montezuma Well; Artists provide their own linens, personal items and transportation; Artwork: Upon completion of the residency, -

Archaeological and Historic Preservation in Tampa, Florida Dawn Michelle Hayes University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Archaeological and Historic Preservation in Tampa, Florida Dawn Michelle Hayes University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Law Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hayes, Dawn Michelle, "Archaeological and Historic Preservation in Tampa, Florida" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4901 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological and Historic Preservation in Tampa, Florida by Dawn Michelle Hayes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Antoinette Jackson, Ph.D. Cheryl Rodriguez, Ph.D. Beverly Ward, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 18, 2013 Keywords: law, museums, neighborhood associations, government, community Copyright © 2013, Dawn Michelle Hayes Dedication To my grandparents: Grandma D.D., Grandpa Cos, Grandma Virginia, Granddad, Nonnie, Topper, and Ralph. Acknowledgments A tremendous thank-you to the members of the Central Gulf Coast Archaeological Society and the Old Seminole Heights Neighborhood Association‟s Preservation Committee, who allowed me to work with them and learn from them for the past several years, not only participating in the research, but keeping it and my writing on track. -

Apache Stronghold Excerpts of Record

Case: 21-15295, 02/23/2021, ID: 12014184, DktEntry: 6-2, Page 1 of 232 No. 21-15295 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ In the United States Court of Appeals for The Ninth Circuit APACHE STRONGHOLD, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Arizona Honorable Steven P. Logan (2:21-cv-00050-PHX-SPL) __________________________________________________________________ EXCERPTS OF RECORD __________________________________________________________________ MICHAEL V. NIXON LUKE W. GOODRICH 101 SW Madison Street #9325 Counsel of Record Portland, OR 97207 MARK L. RIENZI (503) 522-4257 DIANA M. VERM [email protected] JOSEPH C. DAVIS CHRISTOPHER PAGLIARELLA CLIFFORD LEVENSON DANIEL D. BENSON th 5119 North 19 Street, Suite K THE BECKET FUND FOR Phoenix, AZ 85015 RELIGIOUS LIBERTY (602) 544-1900 1919 Pennsylvania Ave. NW [email protected] Suite 400 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 955-0095 [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant Case: 21-15295, 02/23/2021, ID: 12014184, DktEntry: 6-2, Page 2 of 232 TABLE OF CONTENTS Doc. Date Document Description Page 57 2/12/2021 Order regarding Temporary Restraining Order ER001 and Preliminary Injunction 2/03/2021 Transcript of Hearing on Motion for ER024 Preliminary Injunction 7-1 1/14/2021 Declaration of Cranston Hoffman Jr. ER120 7-2 1/14/2021 Declaration of Clifford Levenson ER123 7-3 1/14/2021 Declaration of Naelyn Pike ER125 7-4 1/14/2021 Declaration of Wendsler Nosie, Sr., Ph.D. ER136 15-1 1/20/2021 Declaration of John R. Welch, Ph.D. ER149 18-1 1/21/2021 Ex.