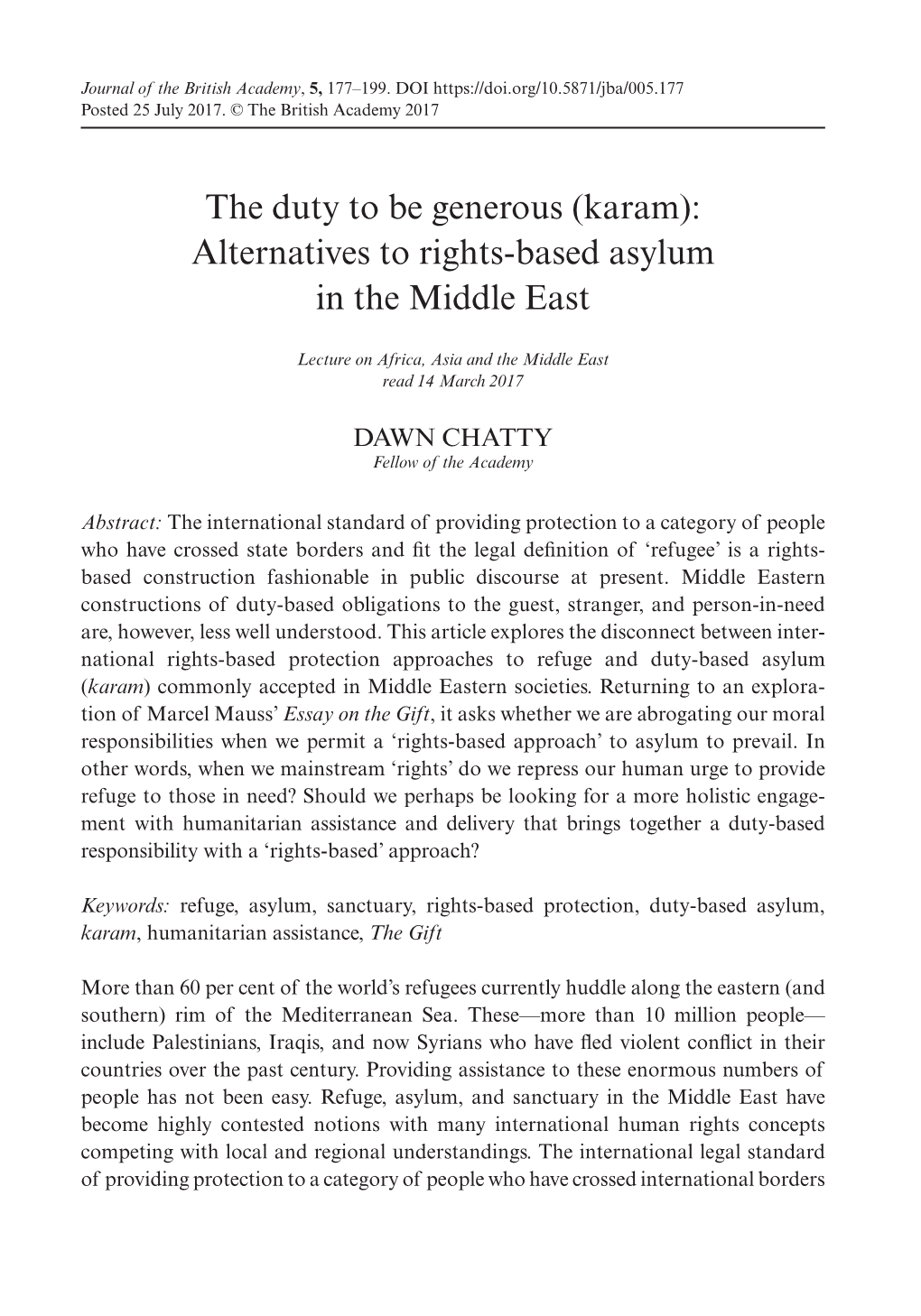

(Karam): Alternatives to Rights-Based Asylum in the Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Champ Readies for Belmont Breeders= Cup

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here THE CHAMP READIES FOR BELMONT GLENEAGLES, FOUND TO BYPASS EPSOM GI Kentucky Derby and GI Preakness S. winner The Coolmore partners= dual Guineas winner American Pharoah (Pioneerof the Nile) registered his last Gleneagles (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) and Group 1-winning filly serious work before Saturday=s GI Belmont S. under Found (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) are no longer under cloudy skies Monday at consideration for Saturday=s Churchill Downs. The bay G1 Epsom Derby, and both covered five panels in will target mile races at 1:00.20 (video) with Royal Ascot. Martin Garcia in the irons Gleneagles was removed shortly after the from the Classic at renovation break. Monday=s scratching stage Churchill clocker John and will head to the G1 St. Nichols recorded 1/8-mile James=s Palace S. on the opening day of the Royal fractions in :13, :25 meeting June 16. Found, (:12), :36.60 (11.60) and who has been second in :48.60 (:12). He galloped Gleneagles winning the Irish both starts this year out six furlongs in 1:13, 2000 Guineas including the G1 Irish 1000 seven-eighths in 1:26 and Racing Post Photo Guineas May 24, will a mile in 1:39.60. contest the G1 Coronation Baffert noted how S. June 19. Found would have had to be supplemented pleased he was with the to the Derby at a cost of ,75,000. Coolmore and American Pharoah work later in the morning. trainer Aidan O=Brien are expected to be represented in Horsephotos AEverything went really the Derby by G3 Chester Vase scorer Hans Holbein well today,@ Hall of Fame (GB) (Montjeu {Ire}), owned in partnership with Teo Ah trainer Bob Baffert said outside Barn 33. -

NL-Spring-2020-For-Web.Pdf

RANCHO SAN ANTONIO Boys Home, Inc. 21000 Plummer Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311 (818) 882-6400 Volume 38 No. 1 www.ranchosanantonio.org Spring 2020 God puts rainbows in the clouds so that each of us - in the dreariest and most dreaded moments - can see a possibility of hope. -Maya Angelou A REFLECTION FROM BROTHER JOHN CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY I would like to share with you a letter from a parent: outh develop a sense of identity and value “Dear All of You at Rancho, Ythrough culture and connections. To increase cultural awareness and With the simplicity of a child, and heart full of sensitivity within our gratitude and appreciation of a parent…I thank Rancho community, each one of you, for your concern and giving of Black History Month yourselves in trying to make one more life a little was celebrated in Febru- happier… ary with a fun and edu- I know they weren’t all happy days nor easy days… cational scavenger hunt some were heartbreaking days… “give up” days… that incorporated impor- so to each of you, thank you. For you to know even tant historical facts. For entertainment, one of our one life has breathed easier because you lived, this very talented staff, a professional saxophone player, is to have succeeded. and his bandmates played Jazz music for our youth Your lives may never touch my son’s again, but I during our celebratory dinner. have faith your labor has not been in vain. And to each one of you young men, I shall pray, with ACTIVITIES DEPARTMENT UPDATE each new life that comes your way… may wisdom guide your tongue as you soothe the hearts of to- ancho’s Activities Department developed a morrow’s men. -

PDF Fileiranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of A

Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Working Paper No. 2021/3 January 2021 The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration www.ryerson.ca/rcis www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration Working Paper No. 2021/3 Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Ryerson University Series Editors: Anna Triandafyllidou and Usha George The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration at Ryerson University. Working Papers present scholarly research of all disciplines on issues related to immigration and settlement. The purpose is to stimulate discussion and collect feedback. The views expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect those of the RCIS or the CERC. For further information, visit www.ryerson.ca/rcis and www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration. ISSN: 1929-9915 Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License A. Moghadam Abstract In this paper I examine the way modalities of mobility and settlement contribute to the socio- economic stratification of the Iranian community in Dubai, while simultaneously reflecting its segmented nature, complex internal dynamics, and relationship to the environment in which it is formed. I will analyze Iranian migrants’ representations and their cultural initiatives to help elucidate the socio-economic hierarchies that result from differentiated access to distinct social spaces as well as the agency that migrants have over these hierarchies. In doing so, I examine how social categories constructed in the contexts of departure and arrival contribute to shaping migratory trajectories. -

SPECIAL ESSAY: Kurds in Iraq and Syria: Aspirations and Realities in a Changing Middle East See P

FMSO.LEAVENWORTH.ARMY.MIL/OEWATCH Vol. 5 Issue #07 July 2015 Foreign Military Studies Office OEWATCH FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT SPECIAL ESSAY: Kurds in Iraq and Syria: Aspirations and Realities in a Changing Middle East See p. 71 TURKEY Helicopter 3 A New Kurdish Star in Turkish Politics 27 The Hair-Raising Business of Assassins for Hire RUSSIA, UKRAINE 4 Kurds Push Back ISIS in Tal Abyad 28 The New Generation Cartel of Jalisco “Grows 44 Russian Missiles that Compel to Peace 5 Turkey to Open Military Base in Qatar Like Cancer” in Mexico 46 Russia Puts US Navy on Notice with Improved “Shipping Container” Missile MIDDLE EAST INDO-PACIFIC ASIA 48 3D Printers Will “Bake” Future Russian UAVs 7 Countering the Islamic State inside Iran 29 A Controversial Project: Building the Kra Canal 50 Russia Fields New Tactical C2 System with 8 Son of Former President Sent to Prison 31 Piracy on the Rise in Southeast Asia FBCB2-like Capabilities 9 “We Are at War with the United States and its 32 Marcos Expresses Concern Over Bangsamoro 52 Russian Airborne Will Add Division, and Expand Allies” Police Turning into a Private Military to 60,000 Paratroopers 10 Syria’s Army of Conquest 33 Indonesian Leader Reaffirms the Government’s 54 Russian Federation Opens First Joint Training 12 Saudi Arabia’s Border Troubles Commitment to Religious Harmony Base and Simulation Center 34 ASEAN-Chinese Declaration Put to the Test 56 Armenia and Iran Discuss Military Cooperation AFRICA -

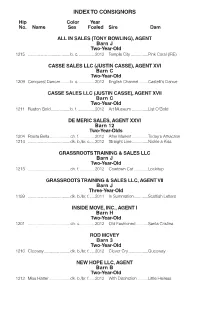

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn J Two-Year-Old 1215 ................................. ......b. c. ...............2012 Temple City ................Pink Coral (IRE) CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVI Barn C Two-Year-Old 1209 Conquest Dancer .........b. c. ...............2012 English Channel ........Castelli's Dance CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVII Barn C Two-Year-Old 1211 Ruston Gold ..................b. f. ................2012 Art Museum ...............List O'Gold DE MERIC SALES, AGENT XXVI Barn 12 Two-Year-Olds 1204 Rosita Bella ...................ch. f. ..............2012 After Market ...............Today's Attraction 1214 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ....2012 Straight Line ...............Nickle a Kiss GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC Barn J Two-Year-Old 1213 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2012 Cowtown Cat .............Lockitup GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC, AGENT VII Barn J Three-Year-Old 1199 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f. .....2011 In Summation .............Scottish Letters INSIDE MOVE, INC., AGENT I Barn H Two-Year-Old 1201 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Old Fashioned ...........Santa Cristina ROD MCVEY Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 1216 Cleeway ........................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 Clever Cry ..................Queeway NEW HOPE LLC, AGENT Barn B Two-Year-Old 1212 Miss Hatter ....................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 With Distinction -

IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay Mare (Branded Nr Sh

Barn J Stables 29-36, 45-52, 61-64 On Account of EDINGLASSIE STUD, Muswellbrook (As Agent) Lot 600 IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay mare (Branded nr sh. off sh.) Foaled 2001 1 Nijinsky ...........................by Northern Dancer ... Caerleon ......................... SIRE Foreseer .................... by Round Table ........... GENEROUS (IRE) ..... Master Derby ............. by Dust Commander .... Doff the Derby ............... Margarethen .............. by Tulyar .................... Storm Bird .................. by Northern Dancer ... DAM Bluebird (USA) ................ Ivory Dawn ................ by Sir Ivor ................... IMCO RESOURCE (IRE) Saratoga Six ............... by Alydar .................... 1996 Sasimoto ....................... Mobcap ...................... by Tom Rolfe .............. GENEROUS (IRE) (1988). 5 wins, Ascot King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Diamond S., Gr.1. Sire of 995 rnrs, 652 wnrs, 45 SW, inc. SW Catella, etc. Sire of the dams of SW Gingernuts, Lion Tamer, Golan, Survived, Nahrain, Mourinho, We Can Say it Now, Proportional, Al Shemali, Mackintosh, Dandino, No Evidence Needed, Armure, Tartan Bearer, Essential Edge, Tungsten Strike, High Accolade, Black Moon, Vote Often, etc. 1st Dam IMCO RESOURCE (IRE), by Bluebird (USA). 2 wins at 2 at 1600m, Rome Premio Disco Rosso. Dam of 8 named foals, all raced, 5 winners, inc:- THAT'S NOT IT (g by Foreplay). 2 wins at 1100m, 1200m, $209,540, MVRC Red Anchor S., Gr 3, 2d VRC Moomba P., L. Impinge (f by Generous (Ire)). 3 wins. See below. 2nd Dam SASIMOTO, by Saratoga Six. 5 wins–3 at 2–1000m to 1400m, Milan Criterium Nazionale, L, Rome Premio Aniene, L, 3d Rome Criterium Femminile, L. Half- sister to NOTEBOOK. Dam of 11 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, inc:- Blue Shift. 8 wins 1000m to 1408m, Rome Premio Nipissing. -

Islamic Republic of Iran (Persian)

Coor din ates: 3 2 °N 5 3 °E Iran Irān [ʔiːˈɾɒːn] ( listen)), also known اﯾﺮان :Iran (Persian [11] [12] Islamic Republic of Iran as Persia (/ˈpɜːrʒə/), officially the Islamic (Persian) ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾران Jomhuri-ye ﺟﻤﮭﻮری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾﺮان :Republic of Iran (Persian Eslāmi-ye Irān ( listen)),[13] is a sovereign state in Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi-ye Irān Western Asia.[14][15] With over 81 million inhabitants,[7] Iran is the world's 18th-most-populous country.[16] Comprising a land area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,37 2 sq mi), it is the second-largest country in the Middle East and the 17 th-largest in the world. Iran is Flag Emblem bordered to the northwest by Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan,[a] to the north by the Caspian Sea, to the Motto: اﺳﺗﻘﻼل، آزادی، ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ northeast by Turkmenistan, to the east by Afghanistan Esteqlāl, Āzādi, Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi and Pakistan, to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf ("Independence, freedom, the Islamic of Oman, and to the west by Turkey and Iraq. The Republic") [1] country's central location in Eurasia and Western Asia, (de facto) and its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz, give it Anthem: ﺳرود ﻣﻠﯽ ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾران geostrategic importance.[17] Tehran is the country's capital and largest city, as well as its leading economic Sorud-e Melli-ye Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi-ye Irān ("National Anthem of the Islamic Republic of Iran") and cultural center. 0:00 MENU Iran is home to one of the world's oldest civilizations,[18][19] beginning with the formation of the Elamite kingdoms in the fourth millennium BCE. -

The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of “Black” Identities in Entertainment

Africana Studies Faculty Publications Africana Studies 12-2015 The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Jennifer Bloomquist Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac Part of the African American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bloomquist, Jennifer. "The inM strel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment." Journal of African American Studies 19, no. 4 (December 2015). 410-425. This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac/22 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Abstract Linguists have long been aware that the language scripted for "ethnic" roles in the media has been manipulated for a variety of purposes ranging from the construction of character "authenticity" to flagrant ridicule. This paper provides a brief overview of the history of African American roles in the entertainment industry from minstrel shows to present-day films. I am particularly interested in looking at the practice of distorting African American English as an historical artifact which is commonplace in the entertainment industry today. -

ISIS and the Sunni Separatists Aim Fire at Iran Visit WEB Receive Newsletter

Opinion Document 62/2017 5 June, 2017 Ely Karmon* ISIS and the Sunni Separatists Aim Fire at Iran Visit WEB Receive Newsletter ISIS and the Sunni Separatists Aim Fire at Iran Abstract: Iran has a central and controversial role in Middle East politics. It is on the one hand one of the intervening actors in the conflicts of the zone and on the other it suffers from terrorism in its territory, in the Baluchistan and Iranian Kurdistan as well as from ISIS. It is to be foreseen an increase of the terrorist activity of this group in the country once the ISIS is defeated in Syria and Irak. Keywords: Iran, terrorism, ISIS, Baluchistan, Kurdistan * NOTE: The ideas contained in the Opinion Documents are the responsibility of their authors, without necessarily reflecting the thinking of the IEEE or the Ministry of Defense. Documento de Opinión 62/2017 1 ISIS and the Sunni Separatists Aim Fire at Iran Ely Karmon The ISIS threat On March 26, 2017, the ISIS information office in Diyala Province, Iraq, published a 37- minute video in Farsi, with some parts in the Baluchi dialect, titled, "Persia – Between Yesterday and Today." The video accuses Iranian Shi'ites of committing many crimes against Sunnis and oppressing the Sunni population of Iran, "exporting the revolution," spreading Shi'ism, and secretly collaborating with the U.S. and Israel. The main speakers in the video are Abu Faruq al-Farisi, speaking Farsi, Abu Mujahid al- Baluchi, speaking Baluchi, and Abu Sa'd al-Ahwazi (from the Ahwaz region). The three speakers call on Iranian Sunnis to rise up against the current Iranian regime and “join the path of jihad.” The group is comprised of "Persian" fighters belonging to the Salman Al- Farisi Brigade, training in urban combat and firing at targets with images of Khomeini, Khamenei, and other Iranian leaders.1 Consistent with ISIS practice, the video documents the execution of four members of Iranian-backed Shi'ite militias in Iraq. -

Iran and the Persian Gulf

HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series Symbolic Name Strategies: Iran and the Persian Gulf Vedran Obućina Number 14: March 2015 About the Author Vedran Obućina is a Political scientist at the Society for Mediterranean Studies, Rijeka, Croatia. He is a PhD researcher on topic of Political Symbolism of the Islamic Republic. Disclaimer The views expressed in the HH Sheikh Nasser al- Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the School or of Durham University. These wide ranging Research Working Papers are products of the scholarship under the auspices of the al-Sabah Programme and are disseminated in this early form to encourage debate on the important academic and policy issues of our time. Copyright belongs to the Author(s). Bibliographical references to the HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series should be as follows: Author(s), Paper Title (Durham, UK: al-Sabah Number, date). 2 | P a g e Symbolic Name Strategies: Iran and the Persian Gulf Vedran Obućina INTRODUCTION National and regional identities have always been and still are connected to territory. The sovereignty is largely perceived biased to a territory, although there are some authors who regard territoriality and state autonomy as irrelevant for the sovereignty. Of course, overwhelming number of countries in the world have territory. However, a country does not stem from nature. Rather, it is imaginative formation, and sovereignty cannot be based exclusively on territory, but primarily on imaginative community. The state sovereignty is by far the end result of particular discourse and imaginary. -

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO)

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Ascot Racecourse Background Information for the 65th Running Saturday, July 25, 2015 Winners of the Investec Derby going on to the King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Unbeaten Golden Horn, whose victories this year include the Investec Derby and the Coral-Eclipse, will try to become the 14th Derby winner to go on to success in Ascot’s midsummer highlight, the Group One King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO), in the same year and the first since Galileo in 2001. Britain's premier all-aged 12-furlong contest, worth a boosted £1.215 million this year, takes place at 3.50pm on Saturday, July 25. Golden Horn extended his perfect record to five races on July 4 in the 10-furlong Group One Coral- Eclipse at Sandown Park, beating older opponents for the first time in great style. The three-year-old Cape Cross colt, owned by breeder Anthony Oppenheimer and trained by John Gosden in Newmarket, captured Britain's premier Classic, the Investec Derby, over 12 furlongs at Epsom Downs impressively on June 6 after being supplemented following a runaway Betfred Dante Stakes success at York in May. If successful at Ascot on July 25, Golden Horn would also become the fourth horse capture the Derby, Eclipse and King George in the same year. ËËË Three horses have completed the Derby/Eclipse/King George treble in the same year - Nashwan (1989), Mill Reef (1971) and Tulyar (1952). ËËË The 2001 King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes saw Galileo become the first Derby winner at Epsom Downs to win the Ascot contest since Lammtarra in 1995. -

P Edigree Insights

Andrew Caulfield, June 29, 2004–Grey Swallow (Ire) P EDIGREE INSIGHTS The presence among the broodmare sires of several other notable mile-and-a-half performers meant that BY ANDREW CAULFIELD Daylami did well to come up with eight winners from his first 26 runners in Britain and Ireland, with further BUDWEISER IRISH DERBY-G1, i1,199,100, The winners in France and Norway. His daughter Bay Tree Curragh, 6-27, 3yo, c/f, 1 1/2mT, 2:28.70, gd/fm. had become his first stakes winner and his second, Grey 1--sGREY SWALLOW (IRE), 126, c, 3, by Daylami (Ire) Swallow, was rated the second-best two-year-old colt 1st Dam: Style Of Life, by The Minstrel of 2003. Daylami also earned black type through the 2nd Dam: Bubinka, by Nashua speedy filly Birthday Suit and the Group 1-placed Day or 3rd Dam: Stolen Date, by Sadair Night. I had also been impressed by another Daylami (150,000gns yrl ‘02 TATHOU). O-Rochelle Quinn; colt, Thajja, but injury prevented this youngster from B-Mrs C L Weld; T-D Weld; J-P Smullen; i736,600. adding to his debut win. Lifetime Record: 6-4-0-1, i882,011. *1/2 to Central The winners have continued to flow from Daylami's Lobby (Ire) (Kenmare {Fr}), GSP-Fr, $232,027. first crop, with Hidden Hope becoming his third stakes Click for the free brisnet.com catalogue-style pedigree winner in the Cheshire Oaks, while Day or Night failed or the racingpost.co.uk chart. by only a short neck to take the G2 Prix Greffulhe.