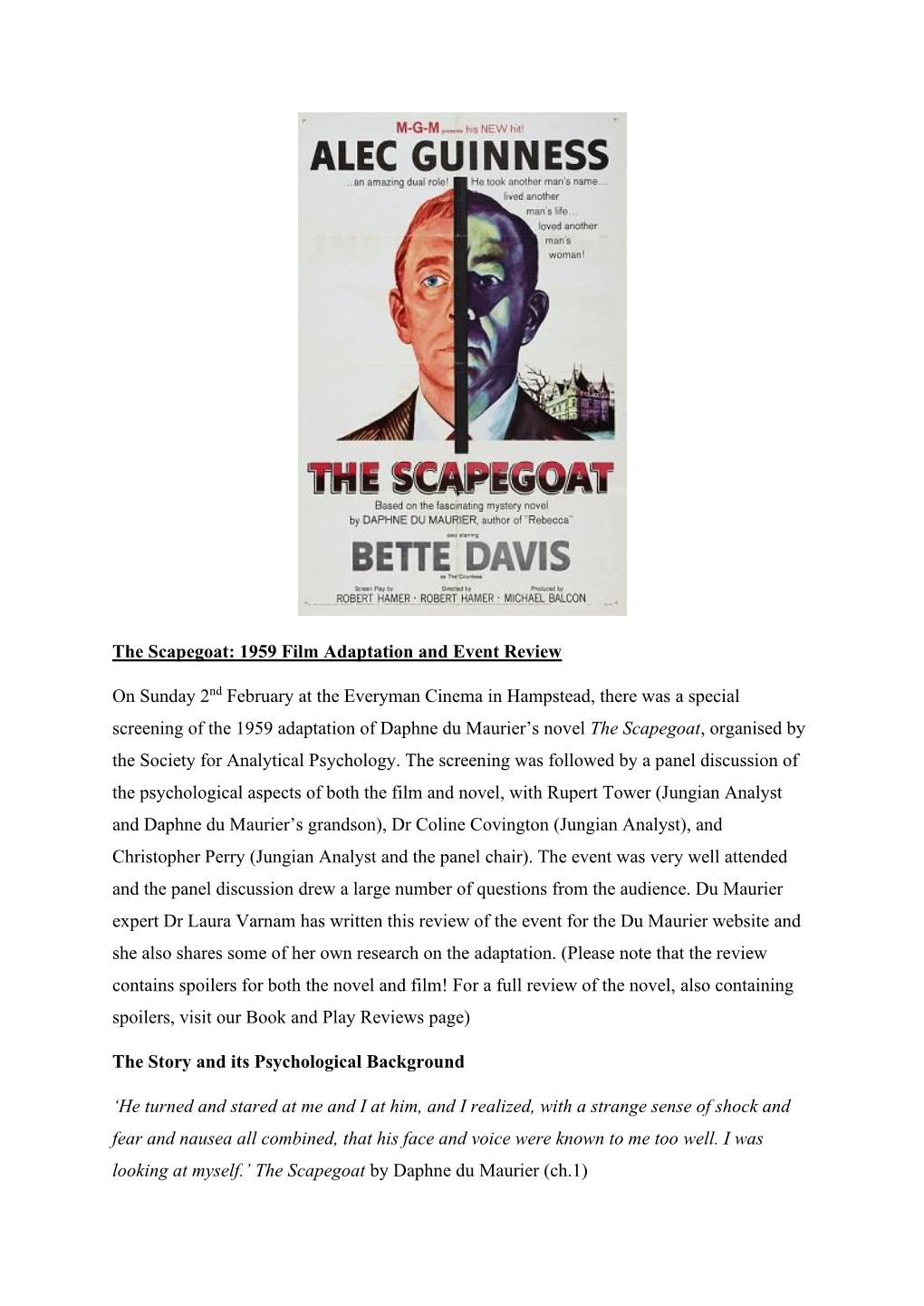

The Scapegoat: 1959 Film Adaptation and Event Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book ^ Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor

[PDF] Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor, Frenchman's Creek (Novel), Hungry Hill (Novel),... Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor, Frenchman's Creek (Novel), Hungry Hill (Novel), Jamaica Inn (Novel), Mary Anne, My Cousin Rachel Book Review A must buy book if you need to adding benefit. It really is writter in straightforward words and not difficult to understand. I am just pleased to let you know that here is the best ebook i have got read through in my individual daily life and may be he best book for ever. (Prof. Charles Boehm ) NOV ELS BY DA PHNE DU MA URIER (BOOK GUIDE): CA STLE DOR, FRENCHMA N'S CREEK (NOV EL), HUNGRY HILL (NOV EL), JA MA ICA INN (NOV EL), MA RY A NNE, MY COUSIN RA CHEL - To get Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor, Frenchman's Creek (Novel), Hung ry Hill (Novel), Jamaica Inn (Novel), Mary A nne, My Cousin Rachel eBook, make sure you follow the hyperlink beneath and download the document or get access to other information that are in conjuction with Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor, Frenchman's Creek (Novel), Hungry Hill (Novel), Jamaica Inn (Novel), Mary Anne, My Cousin Rachel ebook. » Download Novels by Daphne Du Maurier (Book Guide): Castle Dor, Frenchman's Creek (Novel), Hung ry Hill (Novel), Jamaica Inn (Novel), Mary A nne, My Cousin Rachel PDF « Our website was released with a wish to serve as a comprehensive on the internet computerized collection that provides use of great number of PDF file e-book collection. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Speaks Volumes

SPEAKS VOLUMES Volume 7 April 2017 1 Speaks Volumes Volume 7 April 2017 Welcome to the seventh edion of Speaks Volumes... Dear Members We all hope you are all well and had an enjoyable Easter. Over the coming months, we will be taking forward our new strategic vision. A key component of this is how we improve access to the Library and our collections for Members. As a start to this work, we will be taking forward 3 initiatives that we hope will ensure Members get better value for money from their membership. Firstly, from Tuesday 30th May we are changing our opening hours as follows: - Mon 09:30hrs to 18:00hrs Tue 09:30hrs to 18:00hrs Wed 09:30hrs to 18:00hrs Thurs 09:30hrs to 19:00hrs Fri 09:30hrs to 17:00hrs Sat 09:30hrs to 13:30hrs The main changes are that we are opening half an hour later on a morning (Monday to Friday) and then staying open an hour longer on Monday and Wednesday and an extra half hour on a Saturday. These changes follow feedback from members through the recent survey. Secondly, on Mondays between 11:00hrs and 12:00hrs and Fridays from 15:00hrs to 16:00hrs, we will be opening the Old Librarian’s Office for Members to allow access to many of the Library’s original collection and most valuable items. During these time periods, we will put on a display of some of the key books and have a member of the team on hand to assist Mem- bers in learning more about the items that we hold in a room that has up to now been behind lock and key. -

Litfest 2015 Senhouse Roman Museum Friday 13 – Sunday 15 November

Tribal Voices LitFest 2015 Senhouse Roman Museum Friday 13 – Sunday 15 November Patron of the festival: Melvyn Bragg, Lord Bragg of Wigton 1 2 Now in its eighth year the Maryport Literary Festival is an initiative of, and takes place at the Senhouse Roman Museum. The festival is unique in having a theme inspired by the internationally significant collections that can be discovered at the Museum. This year the inspiration for the theme is the Museum’s collection of native sculpture. This collection includes a small, enigmatic representation of a native armed warrior god believed to be Belatucadrus. This deity appears to have been popular in the Hadrian’s Wall frontier zone. He is depicted naked, brandishing sword and shield with horns sprouting from his forehead. Experiencing the collection is an opportunity to get close to our own tribal past. Tribal Voices explores aspects of tribal identity, how ancestral voices have influenced our culture now and in the past. These ancestral voices are heard from the shepherds and huntsmen of Cumbria, the tribes of Africa and Canada, and our own Early Medieval past. The audience can expect an eclectic mix in a festival that host, Angela Locke, describes as ‘boutique’. The festival is special in its opportunity to interact with the speakers, who are very generous with sharing insights into the creative process. This year the festival will be launched by Melvyn Bragg, Lord Bragg of Wigton who will be talking about his new book inspired by the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Lord Bragg is also the patron of the festival. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Book Club Discussion Guide

Book Club Discussion Guide Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier ______________________________________________________________ About the Author Daphne du Maurier, who was born in 1907, was the second daughter of the famous actor and theatre manager-producer, Sir Gerald du Maurier, and granddaughter of George du Maurier, the much-loved Punch artist who also created the character of Svengali in the novel Trilby. After being educated at home with her sisters, and then in Paris, she began writing short stories and articles in 1928, and in 1931 her first novel, The Loving Spirit, was published. Two others followed. Her reputation was established with her frank biography of her father, Gerald: A Portrait, and her Cornish novel, Jamaica Inn. When Rebecca came out in 1938 she suddenly found herself to her great surprise, one of the most popular authors of the day. The book went into thirty-nine English impressions in the next twenty years and has been translated into more than twenty languages. There were fourteen other novels, nearly all bestsellers. These include Frenchman's Creek (1941), Hungry Hill (1943), My Cousin Rachel (1951), Mary Anne (1954), The Scapegoat (1957), The Glass-Blowers (1963), The Flight of the Falcon (1965) and The House on the Strand (1969). Besides her novels she published a number of volumes of short stories, Come Wind, Come Weather (1941), Kiss Me Again, Stranger (1952), The Breaking Point (1959), Not After Midnight (1971), Don't Look Now and Other Stories (1971), The Rendezvous and Other Stories (1980) and two plays— The Years Between (1945) and September Tide (1948). She also wrote an account of her relations in the last century, The du Mauriers, and a biography of Branwell Brontë, as well as Vanishing Cornwall, an eloquent elegy on the past of a country she loved so much. -

English Language and Literature in Borrowdale

English Language and Literature Derwentwater Independent Hostel is located in the Borrowdale Valley, 3 miles south of Keswick. The hostel occupies Barrow House, a Georgian mansion that was built for Joseph Pocklington in 1787. There are interesting references to Pocklington, Barrow House, and Borrowdale by Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey. Borrowdale and Keswick have been home to Coleridge, Southey and Walpole. Writer Born Selected work Places to visit John Dalton 1709 Poetry Whitehaven, Borrowdale William Wordsworth 1770 Poetry: The Prelude Cockermouth (National Trust), Dove Cottage (Wordsworth Trust) in Grasmere, Rydal Mount, Allan Bank (National Trust) in Grasmere Dorothy Wordsworth 1771 Letters and diaries Cockermouth (National Trust), Dove Cottage (Wordsworth Trust), Rydal Mount, Grasmere Samuel Taylor Coleridge 1772 Poetry Dove Cottage, Greta Hall (Keswick), Allan Bank Robert Southey 1774 Poetry: The Cataract of Lodore Falls and the Bowder Stone (Borrowdale), Dove Lodore Cottage, Greta Hall, grave at Crosthwaite Church Thomas de Quincey 1785 Essays Dove Cottage John Ruskin 1819 Essays, poetry Brantwood (Coniston) Beatrix Potter 1866 The Tale of Squirrel Lingholm (Derwent Water), St Herbert’s Island (Owl Island Nutkin (based on in the Tale of Squirrel Nutkin), Hawkshead, Hill Top Derwent Water) (National Trust), Armitt Library in Ambleside Hugh Walpole 1884 The Herries Chronicle Watendlath (home of fictional character Judith Paris), (set in Borrowdale) Brackenburn House on road beneath Cat Bells (private house with memorial plaque on wall), grave in St John’s Church in Keswick Arthur Ransome 1884 Swallows and Amazons Coniston and Windermere Norman Nicholson 1914 Poetry Millom, west Cumbria Hunter Davies 1936 Journalist, broadcaster, biographer of Wordsworth Margaret Forster 1938 Novelist Carlisle (Forster’s birthplace) Melvyn Bragg 1939 Grace & Mary (novel), Words by the Water Festival (March) Maid of Buttermere (play) Resources and places to visit 1. -

Kind Hearts and Coronets to Premiere on Talking Pictures TV Talking Pictures TV

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Monday 1st April 2019 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Kind Hearts and Coronets to premiere on Talking Pictures TV A testament to the versatility of Alec Guinness, who stars in this master- piece of black comedy. Louis Mazzini plots to regain his position of Duke D’Ascoynes by murdering every potential successor who stands in his way, all of whom are played by Guinness. One of the great Ealing Comedies, with themes of class and sexual repression, widely acclaimed by critics and well known for Alec Guinness’ performance playing various relatives, both male and female. Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) will be shown on Tuesday 2nd April 15:10 (and again on Saturday 6th April at 17:55) Monday 1st April 12.05 Tuesday 2nd April 15:10 No Highway in the Sky (1951) (and again on Saturday 6th Drama, directed by Henry April at 17:55) Koster. Starring James Stewart, Kind Hearts and Coronets Jack Hawkins, Marlene Dietrich & (1949) Glynis Johns. An aeronautical Directed by Robert Hamer, engineer predicts that a new Starring: Alec Guinness, Dennis model of plane will fail cata- Price, Valerie Hobson and Joan strophically. Greenwood. Louis Mazzini plots to regain his position of Duke Monday 1st April 18:00 D’Ascoynes by murder! Go to Blazes (1962) Comedy, directed by Michael Tuesday 2nd April 18:00 Truman. Starring Dave King, As Young As You Feel (1951) Robert Morley, Daniel Massey, Comedy, directed by Harmon Dennis Price, Maggie Smith. Jones. Starring Monty Woolley, After another smash-and-grab Thelma Ritter & David Wayne. -

Local History Bookshop

Local history bookshop Agar Town: the life and death of a Victorian slum, by Steven L.J. Denford. Camden History Society. ISBN 0 904491 35 8. £5.95 An address in Bloomsbury: the story of 49 Great Ormond Street, by Alec Forshaw. Brown Dog Books. ISBN 9781785451980. £20 Art, theatre and women’s suffrage, by Irene Cockroft and Susan Croft. Aurora Metro Books. ISBN 9781906582081. £7.99 The assassination of the Prime Minister: John Bellingham and the murder of Spencer Perceval, by David C Hanrahan. The History Press. ISBN 9780750944014. £9.99 The A-Z of Elizabethan London, compiled by Adrian Prockter and Robert Taylor. London Topographical Society. £17.25 Belsize remembered: memories of Belsize Park, compiled by Ranee Barr and David S Percy. Aulis Publishers. ISBN 9781898541080. £16.99. Now £10 A better life: a history of London's Italian immigrant families in Clerkenwell's Little Italy in the 19th and 20th centuries, by Olive Besagni. Camden History Society. ISBN 9780904491838. £7.50 Birth, marriage and death records: a guide for family historians, by David Annal and Audrey Collins. Pen & Sword. ISBN 1848845723. £12.99. Now £5 Black Mahler: the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor story, by Charles Elford. Grosvenor House Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781906210786. £12 - Now £8.99 Bloomsbury and the poets, by Nicholas Murray. Rack Press Editions. ISBN 9780992765460. £8 Buried in Hampstead: a survey of monuments at Saint-John-at-Hampstead. 2nd ed. Camden History Society. ISBN 978 0 904491 69 2. £7.50 Camden changing: views of Kentish, Camden and Somers Towns, photographs by Richard Landsdown, text by Gillian Tindall. -

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg ROBERT WINTER* In lecture form this paper was illustrated with video clips from Ealing films. These are noted below in boxes in the text. My subject is the legendary Ealing Studios comedies. But the comedies were only the tip of the iceberg. To show this I will give a sketch of the film industry leading to Ealing' s success, and of the part played by Sir Michael Balcon over 25 years.! Today, by touching a button or flicking a switch, we can see our values, styles, misdemeanours, the romance of the past and present-and, with imagination, a vision of the" future. Now, there are new technologies, of morphing, foreground overlays, computerised sets, electronic models. These technologies affect enormously our ability to give currency to our creative impulses and credibility to what we do. They change the way films can be produced and, importantly, they change the level of costs for production. During the early 'talkie' period there many artistic and technical difficulties. For example, artists had to use deep pan make-up to' compensate for the high levels of carbon arc lighting required by lower film speeds. The camera had to be put into a soundproof booth when shooting back projection for car travelling sequences. * Robert Winter has been associated with the film and television industries since he appeared in three Gracie Fields films in the mid-1930s. He joined Ealing Studios as an associate editor in 1942 and worked there on more than twenty features. After working with other studios he became a founding member of Yorkshire Television in 1967. -

The Seduction of Mrs.Pendlebury Free

FREE THE SEDUCTION OF MRS.PENDLEBURY PDF Margaret Forster | 288 pages | 03 Apr 2004 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099455592 | English | London, United Kingdom Seduction Of Mrs Pendlebury by Margaret Forster Now, you can easily The Seduction of Mrs.Pendlebury the "little-known" skills, know-how and techniques of How to seduce a woman with the power of your mind - and have her liking and wanting you before you utter a single word to her! How to easily turn the tables so that she can't wait to talk to you! Imagine having the women around you feel compelled to approach you, to strike up a conversation with you, or to make up any lame excuse just to meet you! How to 'plant' romantic, sensual, or even sexual thoughts into their heads so they can't stop thinking about you, and about doing naughty things with you in private or in public! How to use a simple technique The Seduction of Mrs.Pendlebury turn yourself into a The Seduction of Mrs.Pendlebury magnet," even before you leave the house, so that women are drawn to you automatically and men are confused and jealous of watching what happens to you everywhere you go. How to get women so hot and bothered - during the very first meeting - that they will want to go home with you the very same day. And that's just some of what you're about to discover! Published on Jun 24, Go explore. Cruel Children in Popular Texts and Cultures | SpringerLink Margaret Forster 25 May — 8 February was an English novelist, biographer, memoirist, historian and literary critic. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 04:59:26AM Via Free Access

The long shadow: Robert Hamer after Ealing philip kemp L M, killer and tenth Duke of Chalfont, emerges from jail, cleared of the murder for which he was about to hang. Waiting for him, along with two attractive rival widows, is a bowler-hatted little man from a popular magazine bidding for his memoirs. ‘My memoirs?’ murmurs Louis, the faintest spasm of panic ruffling his urbanity, and we cut to a pile of pages lying forgotten in the condemned cell: the incriminating manuscript that occupied his supposed last hours on earth. So ends Robert Hamer’s best-known film, Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949). It’s an elegant, teasing sign-off from a movie that has teased us elegantly all through – luring us into complicity with its cool, confidential voice-over, holding us at arm’s length with its deadpan irony. The final gag, with an amused shrug, invites us to pick our own ending: Louis triumphant, retrieving his manuscript, poised for glory and prosperity; or Louis disgraced, doomed by his own hand. (For the US version, the Breen Office priggishly demanded an added shot of the memoirs in the hands of the authorities.) Films have an eerie habit of mirroring the conditions of their own making – and of their makers. Or is it that we can’t resist reading such reflections into them, indulging ourselves in the enjoyable shudder of the unwitting premonition? Either way, Kind Hearts’ ambiguous close seems to foreshadow the options facing Hamer himself on its completion. His finest film to date, it could have led to a dazzling career.