Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 04:59:26AM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Alec Guinness

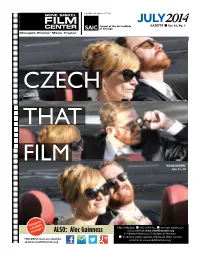

JULY 14 GAZETTE ■20 Vol. 42, No. 7 CZECH THAT FILM HONEYMOON, July 27, 30 Complete schedule FREE SCHEDULE ■ NOT FOR SALE ■ For more information, on page 3 ALSO: Alec Guinness visit us online at: www.siskelfilmcenter.org $11 General Admission, $7 Students, $6 Members ■ To receive weekly updates and special offers, join our FOLLOW US! Join our email list email list at www.siskelfilmcenter.org at www.siskelfilmcenter.org CHICAGO PREMIERE! 2013, Nicholas Wrathall, USA, 89 min. “Entertaining...a thorough, skillfully assembled chronology of the life and times of this all-around man of letters and public gadfly.” —Stephen Holden, The New York Times It would be difficult to find a more fascinating (or July 4th-appropriate) documentary subject than Gore Vidal. Provocative, insightful, eminently quotable, and unfailingly candid, with footholds July 4—10 in the worlds of literature, movies, politics, and sexual politics, Vidal (“I Fri. at 4:45 pm and 7:00 pm; never miss a chance to have sex or appear on television”) embodied Sat. at 6:30 pm and 7:45 pm; the role of public intellectual as fully as any American of the past Sun. at 3:00 pm and 5:30 pm; century. New full-access footage of the still-vital Vidal in the years Mon. at 6:00 pm and 7:45 pm; before his 2012 death provides the framework for a look-back into an Tue. and Thu. at 7:45 pm; incredibly rich life. DCP digital. (MR) Wed. at 6:00 pm CHICAGO PREMIERE! ANNIE O’NEIL IN PERSON! FIRST 2013, Lydia Smith, USA/Spain, 84 min. -

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange By Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby (eds.) London, British Film Institute 2004. ISBN: 1-84457-018-5 (hbk), 1-84457-051-7 (pbk). 164 pp. £16.99 (pbk), £50 (hbk) A review by Martin Barker, University of Wales, Aberystwyth This is the fourth in a line of excellent books to have come out of two conferences held in London, on Hollywood and its audiences. This fourth collection deals specifically with the reception of Hollywood films in some very different counties and cultural contexts. The quality and the verve of the essays in here (they are all, without exception, beautifully written) is testimony to the rise and the potentials of the new historical approaches to audiences (which has, I am pleased to see, sedimented into some on-going cross-cultural research projects on local film exhibition histories). I recommend this book, unreservedly. Its contributors demonstrate so well the potential for many kinds of archival research to extend our understanding of film reception. In here you will find essays on the reception of the phenomenon of Hollywood, and sometimes of specific films, in contexts as different as a mining town in Australia in the 1920s (Nancy Huggett and Kate Bowles), in and through an upmarket Japanese cinema in the aftermath of Japan's defeat in 1946 (Hiroshi Kitamura), in colonial Northern Rhodesia in the period leading up to independence (Charles Ambler), and in and around the rising nationalist movements in India in the 1920-30s (Priya Jaikumar). It is important, in understanding this book, that we pay attention to the specificities of these contexts. -

Dossier De Presse

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent ALEC GUINNESS & Friends ! 7 inoubliables comédies de la Ealing en versions restaurées Tueurs de dames - Noblesse oblige - L’homme au complet blanc - De l’or en barres Whisky à gogo - Passeport pour Pimlico - Tortillard pour Titfield Coffret 3 DVD Alec Guinness The Captain’s Paradise - Barnacle Bill - Vacances sur ordonnance Sortie nationale le 8 octobre 2014 DISTRIBUTION TAMASA PRESSE LES PIQUANTES 5 RUE DE CHARONNE - 75011 PARIS FANNY GARANCHER T. 01 43 59 01 01 T. 01 42 00 38 86 - 06 20 87 80 87 [email protected] [email protected] www.tamasadiffusion.com www. lespiquantes.com ALEC GUINNESS Aux yeux du public, Alec Guinness est l’incarnation même des tra- cerner sa personnalité et son biographe lui-même. Kenneth Tynan, ditions britanniques, avec leur ridicule et leur grandeur. Venu du l’a défini comme « le maître de l’anonymat, la quintessence de théâtre, cet acteur extraordinairement éclectique excelle dans tous la discrétion et de la réserve britannique ». Quant à Guinness, il les genres et est capable d’incarner tous les personnages avec une a déclaré : « Je me suis toujours senti assez mal dans ma peau, égale crédibilité. si bien que j’ai été heureux d’avoir pu me camoufler presque constamment. » En 1979, l’Académie britannique des arts cinématographiques et télévisuels était réunie pour décerner ses prix annuels. Sir Alec Alec Guinness, né à Londres en 1914, a fréquenté différentes Guinness, appelé à recevoir le prix du meilleur acteur de l’année écoles du sud de l’Angleterre. A dix-huit ans, il entre comme ré- pour sa brillante interprétation de l’espion George Smiley dans dacteur dans une agence de publicité. -

Kind Hearts and Coronets to Premiere on Talking Pictures TV Talking Pictures TV

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Monday 1st April 2019 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Kind Hearts and Coronets to premiere on Talking Pictures TV A testament to the versatility of Alec Guinness, who stars in this master- piece of black comedy. Louis Mazzini plots to regain his position of Duke D’Ascoynes by murdering every potential successor who stands in his way, all of whom are played by Guinness. One of the great Ealing Comedies, with themes of class and sexual repression, widely acclaimed by critics and well known for Alec Guinness’ performance playing various relatives, both male and female. Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) will be shown on Tuesday 2nd April 15:10 (and again on Saturday 6th April at 17:55) Monday 1st April 12.05 Tuesday 2nd April 15:10 No Highway in the Sky (1951) (and again on Saturday 6th Drama, directed by Henry April at 17:55) Koster. Starring James Stewart, Kind Hearts and Coronets Jack Hawkins, Marlene Dietrich & (1949) Glynis Johns. An aeronautical Directed by Robert Hamer, engineer predicts that a new Starring: Alec Guinness, Dennis model of plane will fail cata- Price, Valerie Hobson and Joan strophically. Greenwood. Louis Mazzini plots to regain his position of Duke Monday 1st April 18:00 D’Ascoynes by murder! Go to Blazes (1962) Comedy, directed by Michael Tuesday 2nd April 18:00 Truman. Starring Dave King, As Young As You Feel (1951) Robert Morley, Daniel Massey, Comedy, directed by Harmon Dennis Price, Maggie Smith. Jones. Starring Monty Woolley, After another smash-and-grab Thelma Ritter & David Wayne. -

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg ROBERT WINTER* In lecture form this paper was illustrated with video clips from Ealing films. These are noted below in boxes in the text. My subject is the legendary Ealing Studios comedies. But the comedies were only the tip of the iceberg. To show this I will give a sketch of the film industry leading to Ealing' s success, and of the part played by Sir Michael Balcon over 25 years.! Today, by touching a button or flicking a switch, we can see our values, styles, misdemeanours, the romance of the past and present-and, with imagination, a vision of the" future. Now, there are new technologies, of morphing, foreground overlays, computerised sets, electronic models. These technologies affect enormously our ability to give currency to our creative impulses and credibility to what we do. They change the way films can be produced and, importantly, they change the level of costs for production. During the early 'talkie' period there many artistic and technical difficulties. For example, artists had to use deep pan make-up to' compensate for the high levels of carbon arc lighting required by lower film speeds. The camera had to be put into a soundproof booth when shooting back projection for car travelling sequences. * Robert Winter has been associated with the film and television industries since he appeared in three Gracie Fields films in the mid-1930s. He joined Ealing Studios as an associate editor in 1942 and worked there on more than twenty features. After working with other studios he became a founding member of Yorkshire Television in 1967. -

ANNOUNCEMENT from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

ANNOUNCEMENT from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559-6000 PUBLICATION OF FIFTH LIST OF NOTICES OF INTENT TO ENFORCE COPYRIGHTS RESTORED UNDER THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT. COPYRIGHT RESTORATION OF WORKS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT; LIST IDENTIFYING COPYRIGHTS RESTORED UNDER THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT FOR WHICH NOTICES OF INTENT TO ENFORCE RESTORED COPYRIGHTS WERE FILED IN THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE. The following excerpt is taken from Volume 62, Number 163 of the Federal Register for Friday, August 22,1997 (p. 443424854) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: the work is from a country with which LIBRARY OF CONGRESS the United States did not have copyright I. Background relations at the time of the work's Copyright Off ice publication); and The Uruguay Round General (3) Has at least one author (or in the 37 CFR Chapter II Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the case of sound recordings, rightholder) Uruguay Round Agreements Act who was, at the time the work was [Docket No. RM 97-3A] (URAA) (Pub. L. 103-465; 108 Stat. 4809 created, a national or domiciliary of an Copyright Restoration of Works in (1994)) provide for the restoration of eligible country. If the work was Accordance With the Uruguay Round copyright in certain works that were in published, it must have been first Agreements Act; List Identifying the public domain in the United States. published in an eligible country and not Copyrights Restored Under the Under section 104.4 of title 17 of the published in the United States within 30 Uruguay Round Agreements Act for United States Code as provided by the days of first publication. -

Guide to the William K

Guide to the William K. Everson Collection George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center Department of Cinema Studies Tisch School of the Arts New York University Descriptive Summary Creator: Everson, William Keith Title: William K. Everson Collection Dates: 1894-1997 Historical/Biographical Note William K. Everson: Selected Bibliography I. Books by Everson Shakespeare in Hollywood. New York: US Information Service, 1957. The Western, From Silents to Cinerama. New York: Orion Press, 1962 (co-authored with George N. Fenin). The American Movie. New York: Atheneum, 1963. The Bad Guys: A Pictorial History of the Movie Villain. New York: Citadel Press, 1964. The Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel Press, 1967. The Art of W.C. Fields. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967. A Pictorial History of the Western Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1969. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. The Detective in Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1972. The Western, from Silents to the Seventies. Rev. ed. New York: Grossman, 1973. (Co-authored with George N. Fenin). Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1974. Claudette Colbert. New York: Pyramid Publications, 1976. American Silent Film. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, Love in the Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1979. More Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1986. The Hollywood Western: 90 Years of Cowboys and Indians, Train Robbers, Sheriffs and Gunslingers, and Assorted Heroes and Desperados. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1992. Hollywood Bedlam: Classic Screwball Comedies. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1994.