Robert Hamer After Ealing Philip Kemp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

They Drive by Night

Senior’s Matinee They Drive by Night They Drive by Night SPOILER WARNING The following notes give away some of the plot. Director: Arthur Woods ©/Production Company: They Drive by Night is undoubtedly the finest work of director Arthur Warner Brothers First National Productions Woods; a dark film that, although critically well received upon first Executive Producer: Jerome J. Jackson Screenplay and Dialogue: Paul Gangelin, release, was also unfortunately quickly forgotten. The film had to James Curtis, Derek Twist wait another twenty years or more until it finally began to enjoy Based on the novel by: James Curtis reappraisal and to be rightly hailed as a major stylistic and thematic Photography: Basil Emmott * Editor: Leslie Norman * breakthrough, attracting interest in critical circles, not simply for its Art Directors: Peter Proud, Michael Relph * skill as a highly entertaining and well crafted thriller, but for its Music Director: Bretton Byrd Sound: Leslie Murray, H.C. Pearson * realism in respect to both characterisations and settings. Dialogue Director: Anthony Hankey Studio: Teddington Studios Based on a 1938 novel by James Curtis, a writer who set his crime Cast: stories in working-class settings characterised by drabness, corruption Emlyn Williams (Albert Owen ‘Shorty’ Matthews) and brutality, the film adaptation, if it had adhered faithfully to the Anna Konstam (Molly O’Neil) novel, would inevitably have been mired in censorship difficulties. Allan Jeayes (Wally) Ernest Thesiger (Walter Hoover) With a story featuring prostitution, attempted rape and police Jennie Hartley (landlady) brutality, it is little surprise that the BBFC of the period would not Ronald Shiner (Charlie, café proprietor) Anthony Holles (Murray) have countenanced the passing of a script featuring such elements. -

The Grainger Museum in Its Museological and Historical Contexts

THE GRAINGER MUSEUM IN ITS MUSEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXTS Belinda Jane Nemec Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2006 The Australian Centre The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper ABSTRACT This thesis examines the Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne in the context of the history of museums, particularly those in Europe, the United States and Australia, during the lifetime of its creator, Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882–1961). Drawing on the collection of the Grainger Museum itself, and on both primary and secondary sources relating to museum development in the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, the thesis demonstrates that the Grainger Museum reflects many of the concerns of museums of Grainger’s day, especially of the years prior to his relocation to the United States in 1914. Many of those concerns were products of the nationalistic endeavours arising from political upheavals and redefinitions in nineteenth-century Europe, the imperialism which reached its zenith by the First World War, and the racialist beliefs, hierarchies and anxieties accompanying that imperialism. In particular, Grainger’s lifelong concern with racial identity manifested in hierarchical and evolutionary museum interpretations typical of his earlier years. I explore the paradox of Grainger’s admiration for the musical and material culture of the racial ‘other’ and his racially supremacist views, and the way he presented these two apparently conflicting ideologies in his Museum. In elucidating Grainger’s motives for establishing a museum, I argue that Grainger was raised in a social and cultural milieu in which collecting, classifying and displaying cultural material was a popular practice. -

Of Thetheatre Halloween Spooktacular! Dr

VOICE Journal of the Alex Film Society Vol. 11, No. 5 October 22, 2005, 2 pm & 8 pm 10/05 of theTHEATRE Halloween Spooktacular! Dr. Shocker&Friends art Ballyhoo and part bold Pface lie, the SPOOK SHOW evolved from the death of Vaudeville and Hollywood’s need to promote their enormous slate James Whale’s of B pictures. Bride of In the 1930’s, with performance dates growing scarce, a number of magicians turned to movie Frankenstein houses for bookings. The theatre owners decided to program the magic shows with their horror movies and the SPOOK SHOW was born. Who Will Be The Bride of Frankenstein? Who Will Dare? ames Whale’s secrecy regarding class socialists. She attended Mr. Jthe casting of the Monster’s Kettle’s school in London, where she mate in Universal Studio’s follow was the only female student and up to 1931’s hugely successful won a scholarship to study dance Frankenstein set the studio’s with Isadora Duncan in France. publicity machine in motion. With the outbreak of World War I, Speculation raged over who would Lanchester was sent back to London play the newest monster with where, at the age of 11 she began Brigitte Helm, who played Maria her own “Classical Dancing Club”. in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), In 1918, she founded “The Children’s and Phyllis Brooks, a statuesque Theatre” which later morphed into illustrator’s model from New York, “The Cave of Harmony”, a late night considered the front runners. venue where Lanchester performed In spite of Universal’s publicity, one-act plays and musical revues Dr. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Alec Guinness

JULY 14 GAZETTE ■20 Vol. 42, No. 7 CZECH THAT FILM HONEYMOON, July 27, 30 Complete schedule FREE SCHEDULE ■ NOT FOR SALE ■ For more information, on page 3 ALSO: Alec Guinness visit us online at: www.siskelfilmcenter.org $11 General Admission, $7 Students, $6 Members ■ To receive weekly updates and special offers, join our FOLLOW US! Join our email list email list at www.siskelfilmcenter.org at www.siskelfilmcenter.org CHICAGO PREMIERE! 2013, Nicholas Wrathall, USA, 89 min. “Entertaining...a thorough, skillfully assembled chronology of the life and times of this all-around man of letters and public gadfly.” —Stephen Holden, The New York Times It would be difficult to find a more fascinating (or July 4th-appropriate) documentary subject than Gore Vidal. Provocative, insightful, eminently quotable, and unfailingly candid, with footholds July 4—10 in the worlds of literature, movies, politics, and sexual politics, Vidal (“I Fri. at 4:45 pm and 7:00 pm; never miss a chance to have sex or appear on television”) embodied Sat. at 6:30 pm and 7:45 pm; the role of public intellectual as fully as any American of the past Sun. at 3:00 pm and 5:30 pm; century. New full-access footage of the still-vital Vidal in the years Mon. at 6:00 pm and 7:45 pm; before his 2012 death provides the framework for a look-back into an Tue. and Thu. at 7:45 pm; incredibly rich life. DCP digital. (MR) Wed. at 6:00 pm CHICAGO PREMIERE! ANNIE O’NEIL IN PERSON! FIRST 2013, Lydia Smith, USA/Spain, 84 min. -

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange By Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby (eds.) London, British Film Institute 2004. ISBN: 1-84457-018-5 (hbk), 1-84457-051-7 (pbk). 164 pp. £16.99 (pbk), £50 (hbk) A review by Martin Barker, University of Wales, Aberystwyth This is the fourth in a line of excellent books to have come out of two conferences held in London, on Hollywood and its audiences. This fourth collection deals specifically with the reception of Hollywood films in some very different counties and cultural contexts. The quality and the verve of the essays in here (they are all, without exception, beautifully written) is testimony to the rise and the potentials of the new historical approaches to audiences (which has, I am pleased to see, sedimented into some on-going cross-cultural research projects on local film exhibition histories). I recommend this book, unreservedly. Its contributors demonstrate so well the potential for many kinds of archival research to extend our understanding of film reception. In here you will find essays on the reception of the phenomenon of Hollywood, and sometimes of specific films, in contexts as different as a mining town in Australia in the 1920s (Nancy Huggett and Kate Bowles), in and through an upmarket Japanese cinema in the aftermath of Japan's defeat in 1946 (Hiroshi Kitamura), in colonial Northern Rhodesia in the period leading up to independence (Charles Ambler), and in and around the rising nationalist movements in India in the 1920-30s (Priya Jaikumar). It is important, in understanding this book, that we pay attention to the specificities of these contexts. -

Dossier De Presse

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent ALEC GUINNESS & Friends ! 7 inoubliables comédies de la Ealing en versions restaurées Tueurs de dames - Noblesse oblige - L’homme au complet blanc - De l’or en barres Whisky à gogo - Passeport pour Pimlico - Tortillard pour Titfield Coffret 3 DVD Alec Guinness The Captain’s Paradise - Barnacle Bill - Vacances sur ordonnance Sortie nationale le 8 octobre 2014 DISTRIBUTION TAMASA PRESSE LES PIQUANTES 5 RUE DE CHARONNE - 75011 PARIS FANNY GARANCHER T. 01 43 59 01 01 T. 01 42 00 38 86 - 06 20 87 80 87 [email protected] [email protected] www.tamasadiffusion.com www. lespiquantes.com ALEC GUINNESS Aux yeux du public, Alec Guinness est l’incarnation même des tra- cerner sa personnalité et son biographe lui-même. Kenneth Tynan, ditions britanniques, avec leur ridicule et leur grandeur. Venu du l’a défini comme « le maître de l’anonymat, la quintessence de théâtre, cet acteur extraordinairement éclectique excelle dans tous la discrétion et de la réserve britannique ». Quant à Guinness, il les genres et est capable d’incarner tous les personnages avec une a déclaré : « Je me suis toujours senti assez mal dans ma peau, égale crédibilité. si bien que j’ai été heureux d’avoir pu me camoufler presque constamment. » En 1979, l’Académie britannique des arts cinématographiques et télévisuels était réunie pour décerner ses prix annuels. Sir Alec Alec Guinness, né à Londres en 1914, a fréquenté différentes Guinness, appelé à recevoir le prix du meilleur acteur de l’année écoles du sud de l’Angleterre. A dix-huit ans, il entre comme ré- pour sa brillante interprétation de l’espion George Smiley dans dacteur dans une agence de publicité. -

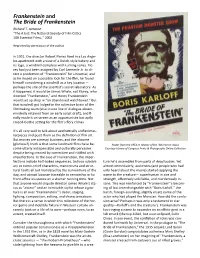

Bride of Frankenstein

Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein Richard T. Jameson “The A List: The National Society of Film Critics 100 Essential Films, ” 2002 Reprinted by permission of the author In 1931, the director Robert Florey lived in a Los Ange- les apartment with a view of a Dutch-style bakery and its logo, a windmill complete with turning vanes. Flo- rey had just been assigned by Carl Laemmle Jr. to di- rect a production of “Frankenstein” for Universal, and as he mused on a possible look for the film, he found himself considering a windmill as a key location— perhaps the site of the scientist’s secret laboratory. As it happened, it would be James Whale, not Florey, who directed “Frankenstein,” and Henry Frankenstein would set up shop in “an abandoned watchtower.” But that windmill got lodged in the collective brain of the filmmaking team (also in one line of dialogue absent- mindedly retained from an early script draft), and fi- nally made it on screen as an opportunistic but aptly crazed-Gothic setting for the film’s fiery climax. It’s all very well to talk about aesthetically unified mas- terpieces and posit them as the definition of film art. But movies are a messy business, and the irksome (glorious?) truth is that some landmark films have be- Poster from the 1953 re-release of the ‘30s horror classic come utterly indispensable and culturally pervasive Courtesy Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Collection despite being created by committee and riddled with imperfections. In the case of Frankenstein, the imper- fections include half-baked sequences, tedious subsidi- ture he’d assembled from parts of dead bodies.