Sixty Olympic Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-20 Annual Report the English Speaking Catholic Council

2019-20 Annual Report The English Speaking Catholic Council Bishop Thomas Dowd Honorary Chairman Executive Committee Paula Celani President Jacques Darche Vice-President William (Bill) Kovalchuk Treasurer Catherine Bolton Secretary Diane Lemay Past-President Board of Directors Cristina Ardelean John Donovan Fr. Raymond Lafontaine Shawn O’Donnell Ellen Roderick Brian Vidal Suzanne Wiseman Advisory Committee Gail Campbell-Tucker Paul Donovan Margaret Lefebvre Clifford Lincoln Mary McDaid Martin Murphy Don Myles Harold Thuringer John Walker Fr. John Walsh Robert Wilkins John Zucchi Staff Anna Farrow Executive Director Suzanne Brown Executive Assistant Message from the President It is with great pleasure that I present the ESCC’s The staff, Board and Advisory Committee were Annual Report for 2019-2020. Through the work saddened to learn of the death of Andrew Fogarty and activities of the past year, the Council has been on February 14, 2020, just a couple of months shy engaged with its core mandate of representing the of his 101st birthday. Andy was deeply involved needs and defending the rights of English-speaking in the life of the English-speaking Catholic Catholics in Quebec. Working with community community and was a founding Director of the partners such as Catholic Action Montreal, Seniors ESCC. Action Quebec (SAQ), Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN), Quebec English-Speaking The emergence of Covid-19, and the subsequent Communities Research Network (QESCREN), containment measures instituted by the provincial APPELE-Quebec and Community Health and government in early March 2020, made for a very Social Services Network (the CHSSN, on which strange end to the fiscal year for the Council. -

SAVE the DATE William Tetley Memorial Symposium, June 19, 2015

Français SAVE THE DATE William Tetley Memorial Symposium, June 19, 2015 The Canadian Maritime Law Association is pleased to invite you to attend a one-day legal symposium to celebrate the contribution of the late Professor William Tetley to maritime and international law and to Quebec society as a Member of the National Assembly and Cabinet Minister and as a great humanist. Details of the program will be communicated shortly. CLE accreditation of the symposium for lawyers is expected. Date: Friday, June 19, 2015 Time: 8h30 -16h30 followed by a Cocktail Reception Place: Law Faculty, McGill University, Montreal, Canada William Tetley, CM, QC Speakers: George R. Strathy, Chief Justice of Ontario Nicholas Kasirer, Quebec Court of Appeal Marc Nadon. Federal Court of Appeal Sean J. Harrington, Federal Court of Canada Prof. Sarah Derrington, The University of Queensland Prof. Dr. Marko Pavliha, University of Ljubljana Prof. Catherine Walsh, McGill University Chris Giaschi, Giaschi & Margolis Victor Goldbloom, CC, QC John D. Kimball, Blank Rome Patrice Rembauville-Nicolle, RBM2L Robert Wilkins More speakers to be confirmed shortly. Cost (in Canadian funds): CMLA Members: $250 Non-members: $300 Accommodations: For those of you from out of town wishing to attend, please note that a block of rooms has been reserved at the Fairmont The Queen-Elizabeth Hotel at a rate of $189 (plus taxes). Please note that the number of rooms is limited and use the following reference no.: CMLA0515. For reservations, tel. (toll- free): 1-800-441-1414 (Canada & USA) or 1-506-863-6301 (elsewhere); or visit https://resweb.passkey.com/go/cmla2015. -

Grandmasfingerprintsamplechapt

© 2011 by Ann Griffiths. All rights reserved. Expanded Version 2014. Published by Redemption Press, PO Box 427, Enumclaw, WA 98022. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any way by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without the prior permission of the copyright holder, except as provided by USA copyright law. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture verses are taken from King James Version of the Bible. ISBN 13: 978-1-63232-928-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2010913350 Tribute to —My grandma— Your life is forever intertwined with mine. Dedicated to —My grandchildren— For all that you are and all that you will be. Contents With Gratitude ......................................ix Introduction ........................................xi 1. My Dearest Victoria ...............................1 2. The Big Black Car . 5 3. Better to Have Loved ..............................11 4. Light in the Darkness .............................21 5. Mystery Man at the Well. 27 6. Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way .................31 7. Grandma’s Brass Bed ..............................37 8. The Good and Bad of Change. 43 Personal Reflection . 48 9. Secret Vow of a Child .............................49 10. The Unspoken Cost ..............................55 11. A Voice Wrapped in Love ..........................59 12. Girls Don’t Play Drums. 65 13. Maybe I Can Write ...............................69 Personal Reflection . 72 14. Silence Runs Deep ...............................73 15. Call in the Night . 79 16. The Reluctant Return .............................85 17. The Lost Is Found. 91 Personal Reflection . 96 18. At the Movies ...................................97 19. New Horizons to Discover ........................101 20. Cross-Border Encounter . 107 21. With Grandma’s Blessing .........................113 22. -

Winter 2012 BISHOP’S Climate Change, Health and Well-Being, Cultural Differences: Exceptional Professors Win Canada Research Chairs You Make It Happen

Your University Magazine No. 36 Winter 2012 BISHOP’S Climate change, health and well-being, cultural differences: exceptional professors win Canada Research Chairs You make it happen I can’t imagine Bishop’s without the Annual Fund. I’m thankful for the scholarship and bursary provided by your charitable “ support. The Annual Fund has helped make my university education possible and given me an amazing experience. Last summer, for example, I was hired as a research intern. It was a wonderful opportunity to put my Biology classes into practice by working with one of my professors closely on a bone density project. Thank you for making it happen through the Annual Fund!” Justin McCarthy 4th year Biology Major from Newport Station NS VP Academic, Students’ Representative Council The Bishop’s Annual Fund Support our students. Make your gift today. 866-822-5210 www.ubishops.ca/gift 6-9 Sarah Feldberg ’00, Jennifer Furlong ’95, Sapna Dayal ’96, Adam Millard ’01, Doug Pawson ’06 Contents Regular features 4 Get involved! Cathy McLean ’82, President of the 5 Principal’s Page Advisors and advocates: Alumni Association, on alumni involvement. a new Council at Bishop’s 14 Campus Notes Getting started in Team Advancement Meet nine individuals in the 4 entrepreneurship, STEPping up your University Advancement Offi ce. communication and more... 6 Alumni Profi les Ronan O’Beirne ’11 writes about fi ve 16 My Space Our Library’s memorial graduates with a passion for social justice. window commemorates the massacre at École Polytechnique. 10 Three new Canada Research Chairs Dr. Cristian Berco, 17 My B.E.S.T. -

Rosh Hashanah 5780: Two Brothers Rabbi Lisa J

Rosh Hashanah 5780: Two Brothers Rabbi Lisa J. Grushcow, D.Phil., Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom Two brothers. Two brothers, standing, at the foot of a mountain. One of them will go up the mountain with their father, a journey fraught with fear and glory, which will transform the history of faith. The other will be left behind. The Akeda, the binding of Isaac which we read on Rosh Hashanah, seems to come out of nowhere. But, like most family legends, there is a back story. What could possibly have happened, to lead to God calling Abraham to sacrifice his son? Most explanations have to do with Abraham – what he did wrong, what he did right. But one zooms in on the relationship between Isaac and Ishmael, the brothers. They are fighting, as siblings do, about who is better, and who is more beloved. Ishmael says to Isaac: “I’m better than you, because I was circumcised when I was thirteen!” And Isaac shoots back: “No, I’m better than you, because I was circumcised when I was only eight days old!” (Note their mothers aren’t invited to give their perspective here; we can only imagine Hagar and Sarah comparing notes). Ishmael replies: “No way! I was thirteen! I could have argued, I could have run away, but I didn’t.” “Oh yeah?” Isaac says, “You think you’re so special? Even if God appeared to me now and told me to cut off one of my limbs, I would do it.”i And it happened after those things, that God tested Abraham, and said, take your son…ii In a world in which the greatest virtue was offering your whole self up to God, no wonder Jewish tradition maintains that Isaac was the son taken up to be sacrificed, and Ishmael was the one left at the foot of the mountain.iii And no wonder Islamic tradition said that Ishmael, their ancestor, was the one that Abraham took. -

List of Participants to the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

HSP HSP/WUF/3/INF/9 Distr.: General 23 June 2006 English only Third session Vancouver, 19-23 June 2006 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM 1 1. GOVERNMENT Afghanistan Mr. Abdul AHAD Dr. Quiamudin JALAL ZADAH H.E. Mohammad Yousuf PASHTUN Project Manager Program Manager Minister of Urban Development Ministry of Urban Development Angikar Bangladesh Foundation AFGHANISTAN Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Dhaka, AFGHANISTAN Eng. Said Osman SADAT Mr. Abdul Malek SEDIQI Mr. Mohammad Naiem STANAZAI Project Officer AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN Ministry of Urban Development Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Musa ZMARAY USMAN Mayor AFGHANISTAN Albania Mrs. Doris ANDONI Director Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Telecommunication Tirana, ALBANIA Angola Sr. Antonio GAMEIRO Diekumpuna JOSE Lic. Adérito MOHAMED Adviser of Minister Minister Adviser of Minister Government of Angola ANGOLA Government of Angola Luanda, ANGOLA Luanda, ANGOLA Mr. Eliseu NUNULO Mr. Francisco PEDRO Mr. Adriano SILVA First Secretary ANGOLA ANGOLA Angolan Embassy Ottawa, ANGOLA Mr. Manuel ZANGUI National Director Angola Government Luanda, ANGOLA Antigua and Barbuda Hon. Hilson Nathaniel BAPTISTE Minister Ministry of Housing, Culture & Social Transformation St. John`s, ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 1 Argentina Gustavo AINCHIL Mr. Luis Alberto BONTEMPO Gustavo Eduardo DURAN BORELLI ARGENTINA Under-secretary of Housing and Urban Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Development Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ms. Lydia Mabel MARTINEZ DE JIMENEZ Prof. Eduardo PASSALACQUA Ms. Natalia Jimena SAA Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Session Leader at Networking Event in Profesional De La Dirección Nacional De Vancouver Políticas Habitacionales Independent Consultant on Local Ministerio De Planificación Federal, Governance Hired by Idrc Inversión Pública Y Servicios Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ciudad Debuenosaires, ARGENTINA Mrs. -

50Th Canadian Regional CPA Conference

50th Canadian Regional CPA Conference Gary Levy The Fiftieth Conference of the Canadian Region, Commonwealth Parliamentary Association takes place in Québec City July 15-21, 2012. This article traces the evolution of the Canadian Region with particular emphasis on previous conferences organized by the Québec Branch. ccording to Ian Imrie, former Secretary- Many provincial branches of CPA existed in name Treasurer of the Canadian Region, the rationale only but the idea of a permanent Canadian association Afor a meeting of Canadian representatives appealed to Speaker Michener. within the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association We can, I think, strengthen the Canadian was partly to help legislators develop an understanding Federation by these conferences. I am sure that of the parliamentary process. Also, this meeting, though it brings all too few people from the western provinces to the Maritimes, If we are to have a united country it is important demonstrates the value of it. I am sure that that elected members from one part of the country the other members from the West, who have visit other areas and gain an appreciation of the not visited Halifax would say that today their problems and challenges of their fellow citizens. I understanding of the Canadian Federation do not think I ever attended a conference, would be greatly helped by conferences held including those in Ottawa, where there were first in the East, then in the West and the Centre.2 not a number of legislators visiting that part of the country for the first time. One should not Premier Stanfield wanted to know more about what underestimate the value of such experiences.1 was going on in other legislatures. -

The CAEP Emergency Ultrasound Curriculum – Objectives and Recommendations For

The CAEP Emergency Ultrasound Curriculum – Objectives and Recommendations for Implementation in Postgraduate Training Paul Olszynski, MD, MEd*; Daniel J Kim**, MD; Jordan Chenkin***, MD; Louise Rang, MD****. On behalf of the CAEP Emergency Ultrasound Committee curriculum working group: Donna Lee, MD; Maja Stachura, MD; Justin Ahn, MD; Oron Frenkel, MD; Moritz Haagar, MD; Mark Bromley, MD; Danny Peterson, MD; Ali Turnquist, MD; Chau Pham, MD; Joseph Newbigging, MD; Conor McKaigney, MD; Melissa Hayward, MD; Andrew Healey, MD; Greg Hall, MD; Charisse Kwan, MD; Michael Woo, MD; Paul Pageau, MD; James Worrall, MD; Frank Myslik, MD; Drew Thompson, MD; Behzad Hassani, MD; Heather Hames, MD; Cristiana Olaru, MD; Laurie Robichaud, MD; Joel Turner, MD; Julie St-Cyr, MD; Annie Giard, MD; Marc-Charles Parent, MD; Maxime Valois, MD; Jean-François Lanctt, MD; David Lewis, MD; Ryan Henneberry, MD; Gillian Sheppard, MD. *University of Saskatchewan **University of British Columbia ***University of Toronto ****Queens University Corresponding author: Dr. Paul Olszynski, [email protected] Executive Summary Emergency Ultrasound (EUS) is now widely considered to be a ‘‘skill integral to the practice of emergency medicine (EM).’’ <1-4> In 2008, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) included EUS as a core competency to its EM training standards, <5> and in 2010, the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) introduced EUS as a terminal training objective for CFPC-EM programs. <6> However, there is considerable heterogeneity in the scope of ultrasound training, curricula, and determination of proficiency. <7- 9> With this in mind, the CAEP Emergency Ultrasound Committee (EUC) formed the EUS Curriculum Working Group, consisting of EUS experts and educators from every EM training site in Canada. -

Loyola of Montreal: Report of the President 1969 to 1973 Index

Loyola of Montreal: Report of the President 1969 to 1973 Index 1969-1971 1972-1973 Report of the President . 5 Report of the President ... ... ..... .... 41 Reports Reports Registrar .... ... .. .. ..... .. ... 11 Registrar ..... .. .. ..... .. .. .... 46 Evening Division ... ...... ... .... 12 Evening Division ... .. ......... 47 Chief Librarian .. .. .... .... .. .. 12 Chief Librarian . .... .. .. ... ...... 48 Physical Education and Athletics . ..... 14 Chaplaincy .. ... ... ...... .. .. .. 49 Financial Aid . .. .... ... .... .. 15 Physical Education and Athletics . .. 49 Development .. ....... .... ... ..... 15 Alumni ... .. ...... .. .. ... ... .. 49 Financial .. .. .. ..... .. ....... .. 15 Financial Aid ..... .. .. .. .. .. 50 Senate Committee on Visiting Lecturers 16 Development ... .... ... .... .. .. ... 50 Faculty Financial ....... .... .. .. .. ... .. 50 awards . ... ... ... ... ....... .. ... 16 Senate Committee on Visiting Lecturers 51 publications, lectures, speeches . .... 17 Faculty doctorates, appointments, promotions . 20 awards .. .. ... ..... ........... 51 new faculty, faculty on leave of publications, lectures, speeches .. ..... 51 absence, departures . ..... .. ...... 21 doctorates, appointments, promotions . 53 new faculty, faculty on leave of absence, departures . ... .. ... ... 54 1971-1972 Report of the President . 24 Reports Registrar . .. .. ... ..... .. .. .... 31 Evening Division ..... ... ......... .. 32 Chief Librarian .... ........ ... ... 32 Chaplaincy . .... ... ... ..... 34 Physical Education and Athletics -

REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1159 Medical

REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1159 Medical Council of Canada.—1964. Nov. 6, Robert M. Dysart, Moncton, N.B.; and Richard S. Duggan, St. David's, Ont.: to be members for a term of four years from Nov. 7, 1964. Dec. 15, Arthur Maxwell House, St. John's, Nfld.: to be a member for a term of four years, vice J. J. Josephson, resigned. Municipal Development and Loan Board.—1964. Feb. 6, J. E. G. Hardy, Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet: to be a member. June 18, A. S. Abell, Director of Federal-Provincial Relations Division, Department of Finance: to be a member and Chair man from Aug. 1, 1964, vice K. W. Taylor. Nov. 12, I. R. Maclennan, Executive Director of Urban Development, Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation: to be a member. National Advisory Council on Fitness and Amateur Sport.—1964. Mar. 5, Earl Nicholson, Charlottetown, P.E.I.; Miss Mary Barker, Ingonish, N.S.; Morris M. Broker, Montreal, Que.; Robert LeBel, Fort Chambly, Que.; John W. Davies, Montreal, Que.; Paul Hauch, London, Ont.; J. L. Edwards, Kingston, Ont.; Paul H. Traynor, Hamil ton, Ont.; Max Avren, Winnipeg, Man.; W. A. R. Orban, Saskatoon, Sask.; M. L. Van VTiet, Edmonton, Alta.; Mrs. May Brown, Vancouver, B.C.; and David Bauer, Vancouver, B.C.: to be members for a term ending Dec. 31, 1965. Marcel de la Sablonniere, Montreal, Que.; and James Worrall, Toronto, Ont.: to be again members for a term ending Dec. 31, 1965. Aug. SO, John E. Merriman, Saskatoon, Sask.: to be a member, vice J. H. Ebbs, resigned. -

Journal Des Débats

journal des Débats Le mardi 14 novembre 1978 Vol. 20 — No 75 Table des matières Dépôt de documents Rapports de l'Ordre des chimistes et de l'Ordre des chiropraticiens 3667 Rapport de la Commission de la fonction publique 3667 Projet de loi no 96 — Loi modifiant de nouveau la Loi de l'instruction publique et modifiant la Loi du Conseil supérieur de l'éducation Première lecture 3667 M. Jacques-Yvan Morin 3667 Questions orales des députés Manifestation des étudiants en réadaptation 3668 Lock-out de l'entreprise Valger 3669 Création d'emplois pour les jeunes 3671 Taux de pollution à Québec 3673 Résolution du PQ de Hull au sujet du journal Le Droit 3674 Congés de maternité et Loi du salaire minimum 3675 Grève au Montreal Star 3676 Félicitations aux maires, conseillers et candidats 3677 Mise aux voix de la motion amendée 3680 Mise aux voix de la motion principale 3680 Travaux parlementaires 3681 Avis de mini-débats 3683 Projet de loi no 83 — Loi modifiant la Loi constituant la Régie des installations olympiques Deuxième lecture 3684 M. Claude Charron 3684 M. George Springate 3688 M. Fernand Grenier 3689 M. Gilbert Paquette 3690 M. André Marchand 3692 M. Maurice Bellemare 3694 M. William Frederic Shaw 3695 M. Lucien Caron 3696 M. Victor Goldbloom 3697 M. Bertrand Goulet 3698 M. Richard Verreault 3698 M. Serge Fontaine 3699 M. Claude Charron 3699 Renvoi à la commission de la jeunesse 3702 Table des matières (suite) Projet de loi no 28 — Loi concernant les droits de chasse et de pêche dans les territoires de la baie James et du Nouveau-Québec Projet de loi no 29 — Loi concernant le régime des terres dans les territoires de la baie James et du Nouveau-Québec Projet de loi no 30 — Loi modifiant de nouveau la Loi de la qualité de l'environnement Deuxième lecture 3702 M. -

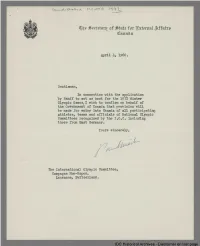

April Ht I960. Gentlemen, in Connection with the Application By

c*_*jk^ kow^oi i^'Y'L April ht I960. Gentlemen, In connection with the application by Banff to act as host for the 1972 Winter Olympic Games, I wish to confirm on behalf of the Government of Canada that provision will be made for entry into Canada of all participating athletes, teams and officials of National Olympic Committees recognized by the I.O.C. including those from East Germany. Yours sincerely, The International Olympic Committee, Campagne Mon-Repos, Lausanne, Switzerland. IOC Historical Archives - Disclaimer on last page JanuaryS , 1966. Gentlemen: In connection with the Canadian Application being made by Banff to host the 1972 Olympic Winter Games, I am authorized to state that while the games are now several years in the future, the Canadian Government anticipates that adequate provision will be made for entry into Canada by all participating athletes, teams, officials, juries etc., from National Olympic Committees and International Amateur Sports Federations recognized by the I.O.C., under the terms of the resolution adopted by the I.O.C. at Madrid in October 1965» The Canadian Government is most anxious to welcome athletes from all over the world for the 1972 Olympic Winter Games, and if the International Olympic Committee requires further expression of the Canadian Government's willingness to accommodate and facilitate the entry of athletes, we would be glad to give such a roquest very sympathetic consideration when the precise nature of these assurances is indicated to us. Tours sincerely, Paul Martin, Secretary of State for External Affairs. e International Olympic Committee Campagne Mon-Repos, Lausanne, Switzerland.