Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDITOR's NOTE: Hallmark Channel Has Breaking News

EDITOR’S NOTE: Hallmark Channel has Breaking News, go to www.crownmediapress.com for more information. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 8, 2015 LACEY CHABERT STARS WITH BRENNAN ELLIOTT AND SEVEN-TIME EMMY® AND FIVE-TIME GOLDEN GLOBE® WINNER EDWARD ASNER IN ‘ALL OF MY HEART’ (wt) A HALLMARK CHANNEL ORIGINAL MOVIE WORLD PREMIERE FEBRUARY 14 Part of Hallmark Channel’s ‘COUNTDOWN TO VALENTINE’S DAY’ Lacey Chabert (“Mean Girls,” “Party of Five,” “A Royal Christmas”), Brennan Elliott (“Debbie Macomber’s Cedar Cove,” “Criminal Minds”) and seven-time Emmy® and five-time Golden Globe® winner Edward Asner (“The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “Elf”) star in “All of My Heart” (wt), a Hallmark Channel Original Movie World Premiere Saturday, February 14 (8p.m. ET/PT, 7C). Greyston Holt (“Bitten,” “Signed, Sealed, Delivered”), Daniel Cudmore (“X-Men: Days of Future Past,” “The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 2”) and Heather Doerksen (“The Cabin in the Woods”) co-star. “All of My Heart” (wt) is part of Hallmark Channel’s ‘COUNTDOWN TO VALENTINE’S DAY,’ a two week celebration featuring nearly 300 hours of fan-favorite romantic movies all leading up to February 14th! A young caterer’s life suddenly changes course when she inherits a country home and learns she must share it with a career-obsessed Wall Street trader. At first, these opposites do not attract, but feelings begin to change when they find themselves having to work side-by-side to restore their newly acquired home “All of My Heart” (wt) is a Front Street Pictures and Better Road Productions Ltd Production. -

Sites Using React · Facebook/React Wiki · Github

Personal Open source Business Explore Pricing Blog Support This repository Search Sign in Sign up facebook / react Watch 3,811 Star 53,928 Fork 9,588 Code Issues 493 Pull requests 97 Projects 0 Wiki Pulse Graphs Sites Using React Wylie Swanson edited this page Nov 14, 2016 · 622 revisions If you use React, don't be shy – edit this page! Pages 18 The Art Of Ping Pong Find a Page… 1stdibs ‐ Online marketplace for antique furniture, jewelry, fashion, and fine art 6play ‐ Video site for the "M6" french TV channel Home 6rooms 2015 03 20 90min 2015 03 27 9flats 2015 04 03 Accio 2015 04 10 Asciinema Adazzle 2015 04 17 AddThis 2015 04 24 ADN Articles and Videos AdRoll ‐ AdRoll Prospecting UI, component library Complementary Tools Afterclasse ‐ Educational website for french students Examples AgileMD Meeting Notes Aha! Algolia ‐ Hosted Search API Meetups Amaze UI ﴾in Chinese﴿ Polyfills Angie's List Projects Airbnb react AirHelp Show 3 more pages… African Exponent ‐ Premier source of reliable African and World news Alipay Clone this wiki locally Andy Tran ‐ CodePen Profile powered by React https://github.com/facebook/react.wiki.git Ant Design AnyList Clone in Desktop Appointment Reminder ARTE ‐ Video site for the ARTE french/german TV channel Asana Assembly Assertible ‐ QA for the Web Atlassian Automattic Avant Avaza Ayasan Backpack Page 1 of 14 Assembled by RunPDF.com BBC Benzinga Beroomers ‐ Find your ideal student home! BetBetr Beyondpad Biblebox BigDecisions ‐ Used React+Flux for calculators. BigRentz BilletFix ‐ Simple ticket management system -

Review Selection Using Micro-Reviews

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE AND DATA ENGINEERING, VOL. 26, NO. X, XXXXX 2014 1 Review Selection Using Micro-Reviews Thanh-Son Nguyen, Hady W. Lauw, Member, IEEE, and Panayiotis Tsaparas, Member, IEEE Abstract—Given the proliferation of review content, and the fact that reviews are highly diverse and often unnecessarily verbose, users frequently face the problem of selecting the appropriate reviews to consume. Micro-reviews are emerging as a new type of online review content in the social media. Micro-reviews are posted by users of check-in services such as Foursquare. They are concise (up to 200 characters long) and highly focused, in contrast to the comprehensive and verbose reviews. In this paper, we propose a novel mining problem, which brings together these two disparate sources of review content. Specifically, we use coverage of micro-reviews as an objective for selecting a set of reviews that cover efficiently the salient aspects of an entity. Our approach consists of a two-step process: matching review sentences to micro-reviews, and selecting a small set of reviews that cover as many micro-reviews as possible, with few sentences. We formulate this objective as a combinatorial optimization problem, and show how to derive an optimal solution using Integer Linear Programming. We also propose an efficient heuristic algorithm that approximates the optimal solution. Finally, we perform a detailed evaluation of all the steps of our methodology using data collected from Foursquare and Yelp. Index Terms—Micro-review, review selection, coverage Ç 1INTRODUCTION ODAY, we can find ample review content in various Web micro-review of the place. -

THESIS the USE of PARATEXTUAL DEVICES in BROADCAST PROMOTION: a CONTENT ANALYSIS of SEASON THREE of GLEE on FACEBOOK Submitted

THESIS THE USE OF PARATEXTUAL DEVICES IN BROADCAST PROMOTION: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SEASON THREE OF GLEE ON FACEBOOK Submitted by Rachel Timmons Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2015 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Kirk Hallahan Scott Diffrient Rosa Martey Copyright by Rachel Timmons 2015 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE USE OF PARATEXTUAL DEVICES IN BROADCAST PROMOTION: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SEASON THREE OF GLEE ON FACEBOOK This study analyzed all Facebook posts during the third season of the Fox Broadcast Network television show Glee (n=763), from August 2011 to May 2012. The study illustrated that Facebook posts can be considered valuable paratextual devices (Gray, 2010b) that can be used in the promotion of a television program. The program’s promoters, who served as Facebook Page administrators, used Facebook for three purposes: build viewership, enhance the live-viewing experience, and build brand awareness and engagement. Visual paratexts, such as images and videos, were used more widely than text-based paratexts. Some of the most frequently employed paratexts included previews/sneak peeks/promos, cast-member specific posts, spoilers or teasers, and music video clips. Posts were about equally split in terms of being related to specific episodes versus the show in general. Almost half of the overall posts displayed high interactivity, which prompted the users to leave the Facebook platform. These posts can be valuable if the show is interested in building brand awareness and enhancing the viewing experience, not just increasing post and Page likes. -

> Home^Ev^Spdper-'^

7 .- Q .DaiVVBr. : ; . 'T . ••; T; ' [ ,... ■ N 'V " '■'"■ ’• •• . - • V..,. -Sv V,';'. ; •; •• (jblO M. Juiiu.DaviV.Dr. ----------- ^ . g } 7 0 b : ^ - C ^ a p , - - -T "-- . ■-7-:-"-^— -j ^ ^ ~ • . ’r ' W ea th er ' H om e — '* ■ .&6lej,.,5[f/iVidy;-:hdyX ...MV m EF in a l , M aagic i V ailey’s; > Home^ev^spdper-'^H om e ■ _ ■ ~ ~ TO. TUESDAY, 0GT0BE !rt7^cF = ^^^ f f i l i S o r t a si M i t t o i a L Tpr tilo Tl = ^^:|S ena;fe-- ijfeRaids^ I u S E E•t iTo Iiivtn ^ R e ' , .Ni^HVnJCEr Tenn. (AP)p ) ’-— j M ssi&r~" Kvi Presideni'Hubert H. Hiim-Hum- ' V. J V B v ' _J»l£ey_aysjf_eiectcd_pcfisidfintsident- ..-M -hc. w ^ stopHbe-bombjngn g . ofoJ - ■ North Vietnam as an "accepta*. • ■ I G l o t ui r e B y 4 5 . ‘blft- riJk" for.peacC 'I f .HariofI^'atiof 'M ;i=;;=shQW^ilKngnes«—tc^-restore :— M WASHINGTONWASl (A P) —— TTho]U^e■^ hofure". :Johnson replied hee would HcfciHefcrring to this sequence of _ . ji_^--Mie^(!(militarizea-2one?- '» ■• , " S a Senate refused. Tuc.sday to cutjacceptcutlaccept upon- Senate confirma-onfirma- events, Sen. Paul J. Fannih.H -" In hia- Hrsc paid nationwide . ■ off.o ff. a filibu.ster against PPresl-jtlon resl-jtlon of a successor. - . '’ - j3,rjZuJj5,rjZi*-iold ih e S e n a te, t h a ^ ‘*.thi* --•'^elci^slon 'broadcast M onday ■ ■ dgiedone T■Johnson’s ■ nominationlon.i'of ^ of SubsSubsequently Warren told"^ Mickey Mouse tjtpcrof .orrange--------- and spcalcing. from1 'SaltSalt - g AbeA be FortasFc lo be' chief justice news cconference that, in1 the in- mcnt iis jin affront to tho Con- „• • i a b City ,before*^flying VKiire.''Ksre. -

D5.1 Market Analysis.Pdf

Europeana Space – Spaces of possibility for the creative reuse of Europeana’s content CIP Best practice network - project number 621037 Deliverable number D5.1 Title Market Analysis Due date Month 6 Actual date of July 2014 delivery to EC Included (indicate Executive Abstract Table of Contents as appropriate) Summary Project Coordinator: Coventry University Prof. Sarah Whatley Priority Street, Coventry CV1 5FB, UK +44 (0) 797 4984304 E-mail: [email protected] Project WEB site address: http://www.europeana-space.eu Page 1 of 102 EUROPEANA SPACE D5.1 Market Analysis Context: Partner responsible for UNIVE deliverable Deliverable author(s) Tomaso Borzomì, Leonardo Buzzavo, Eugenio Pandolfi, Andrea Toffanello Deliverable version number 2.1 Dissemination Level Public X Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) History: Change log Version Date Author Reason for change 1.0 Jul 3rd Tomaso Borzomì, Leonardo 2014 Buzzavo, Eugenio Pandolfi, Andrea Toffanello 2.0 Jul 30th Tomaso Borzomì, Leonardo Review process Buzzavo, Eugenio Pandolfi, Andrea Toffanello; Gregory Markus and Lizzy Komen (NISV) and Tim Hammerton (COVUNI) 2.1 Jul 30th Tim Hammerton Minor amendments Release approval Version Date Name & organisation Role 2.1 31 July Tim Hammerton (COVUNI) Project Manager 2014 Page 2 of 102 EUROPEANA SPACE D5.1 Market Analysis Statement of originality: This deliverable contains original unpublished work except where clearly indicated otherwise. Acknowledgement of previously published material and of the work of others has been made through appropriate citation, quotation or both. -

Editor's Note

EDITOR’S NOTE: Hallmark Channel has Breaking News, go to www.crownmediapress.com for more images and more information. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 8, 2015 A METEOROLOGIST IS THROWN IN TO A WHIRLWIND OF LOVE WHEN KATIE LECLERC AND MICHAEL RADY STAR IN ‘CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF LOVE,’ A HALLMARK CHANNEL ORIGINAL MOVIE WORLD PREMIERE FEBRUARY 8 Stacey Dash and Gregory Harrison Co-Star; Part of Hallmark Channel’s ‘COUNTDOWN TO VALENTINE’S DAY’ Katie Leclerc (“Switched at Birth,” “Beverly Lewis’ The Confession”) and Michael Rady (“Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants,” “Intelligence”) star alongside Stacey Dash (“Clueless,” “Mo’ Money”) and Gregory Harrison (“One Tree Hill”) in “Cloudy With A Chance of Love,” a Hallmark Channel Original Movie World Premiere Sunday, February 8 (8p.m. ET/PT, 7C). “Cloudy With A Chance Of Love” is part of Hallmark Channel’s ‘COUNTDOWN TO VALENTINE’S DAY,’ a two week celebration featuring nearly 300 hours of fan-favorite romantic movies all leading up to February 14th! Quirky meteorologist Deb spends most of her time finishing the passionate pursuit of her Ph.D. in meteorology. The wind of change starts blowing, however, when a handsome news director recruits her to fill in as an on-air weather personality. While the new job comes with a glamorous makeover that catches the eyes of both viewers and her handsome colleague, it also takes her away from her studies at a critical time. When her TV job, academic commitments and new romance swell into a perfect storm, Deb must decide if her future will be spent studying the sky, or broadcasting over the air. -

Royal Crush Two Distinguished Brits Bring Their Queen to the Screen

HO ME (/) AWARDS (/AWARDS) NEWS & MAG AZINE (/NEWS) PHO TO S (/PHO TO S) VIDEO S (/VIDEO S) EVENTS (/EVENTS) ACADEMY (/ACADEMY) FO UNDATIO N (/FO UNDATIO N) ARCHIVES (HTTP://EMMYTVLEG ENDS.O RG /) MEMBERS (/MEMBERS) IN THE MIX September 26, 2016 Royal Crush Two distinguished Brits bring their queen to the screen. Randee Dawn Netflix When he tackled the subject of the British royals for a series about the young Queen Elizabeth II, Peter Morgan was actually NEWS thinking about another insular family. Television “The TV show I admire most is The Sopranos,” says Morgan, creator– Academy executive producer of The Crown, debuting November 4 on Netflix. Governor Lily “They are both stories about a family within a specific and unique Tomlin to Receive (/news/academy anthropology. Tony Soprano’s constant battle was, ‘Which family am I SAG Lifetime news/television most loyal to?’ and for Elizabeth Windsor, it’s, ‘Which Elizabeth am I Achievement academy Award most loyal to?’” governorlily (/news/academy news/television “And the psychiatrist here,” quips executive producer–director Stephen tomlinreceive academy Daldry, “is the prime minister.” saglifetime governorlily The Crown stars Claire Foy as the queen and Matt Smith as her achievement tomlinreceive husband, Philip Mountbatten, and opens shortly before the death of award) saglifetime King George VI (Jared Harris), Elizabeth’s father. He’s preparing Elizabeth for an eventual ascension to the throne, but he’s also hiding achievement his lung cancer. His death from a blood clot in 1952 thrusts her into her award) reign at 26. -

“Farmed and Dangerous”

LancerThe Post May Volume 5 Lancer Post 2014 The Beef With Chipolte By Dimitri Nesbitt Post Staff Writer Occasionally, one has the first-hand experience of harnessing the power of the Internet, and Eastern Wyoming College played host to one such person this past Wednesday night. Greg Peterson, a member of the YouTube phenomenon Peterson Farm Bros., visited the college to discuss “Advocating Agriculture through Social Media.” He joins his brothers Nathan and Kendal in producing parody videos of popular songs titled “Farmer Style” and “I’m Farming and I Grow It” modeled after international hits “Gangnam Style” and “Sexy and I Know It” respectively. In addition to contributing to pop culture, the Peterson brothers have become spokesmen for issues on agriculture, made sensitive through Chipotle’s aggressive campaign against industrial farming and its upcoming “Farmed & Dangerous” TV series. While the Petersons agree with Chipotle’s marketing against “inhumane” and the “unsustainable nature of industrial farming,” the brothers have launched a blog (The Peterson Farm Blog) in disagreement with how Chipotle defines and portrays “family farms” and what humane and ethical agricultural behavior consists of. As 5th generation Kansas farmers, the Peterson brothers write that “our farm is quite large, with an operation of over 1,000 head, and yes, we raise our livestock “conventionally.” That means our cattle are confined in pens, antibiotics are given to “Farmed and Dangerous” revive them when they are sick, and hormones are administered to them to promote healthy growth.” By Nikki Dunovsky This reality, the Petersons say, is the base of what Post Staff Writer Chipotle is discouraging when claiming that it is Since the start of social media through the Internet, people have been able to communicate differently. -

Market Opportunities and Challenges

WP2 : 2nd Screen, Social Media Vision and Challenges D2.2.1: Market Opportunities and Challenges Deliverable Lead: BDS Contributing Partners: BDS, ALL Delivery Date: 2014-10 Dissemination Level: Public Final The purpose of this SAM deliverable D2.2.1 Market Opportunities and Challenges is to deliver an initial description of the potential target market sectors and the prospective customers, in alignment with the SAM vision. Furthermore the report will identify the current state of the market and its challenges and opportunities, the competitors and incumbents and identify the market from the perspective of the use case partners. SAM Public D2.2.1 Document Status Deliverable Lead Barry Smith, BDS Internal Reviewer 1 TIE – Juan Vincente Vidagany Espert, Fran Rodriguez Montero v0.6, 22.10.2014 Internal Reviewer 2 TPVision – Koen Cooreman v0.8, 07.11.2014 Type Deliverable Work Package WP2 – 2nd Screen, Social Media Vision and Challenges ID D2.2.1: Market Opportunities and Challenges Due Date 10.2014 Delivery Date 11.2014 Status For Approval Document History V0.1: First Draft produced by Editor V0.2: Part contributions by BDS and DW V0.3: With edited contributions from majority of contributor partners V0.4: With all contributions from partners – commented and edited V0.5: Edited by Editor Versions V0.6: Final contributions edited by Editor V0.7: First internal reviewers’ comments V0.8: For 2nd Review V0.9: BDS: Final Version BDS: Barry Smith - Rosie Harley - Mark Klose – Document structure, Lead – Sections 2 and 3 TIE: Juan Vte. Vidagany - Fran Rodriguez - Sections 2 and 3 DW: Sections 2 and 3 UA: David Tomás - Section 2 Contributions TPV: Koen Cooreman – Sections 2 and 3 TALK: Fredrik Kronlid – Alex Berman Section 2 ASC: Norman Wessel – Sections 2 and 3 UOR: Marco Tiemann – Section 2 NTUA: Andreas Menychtas - Christina Santzaridou, - Section 2 ALL: SWOT Analysis Contributions Disclaimer The views represented in this document only reflect the views of the authors and not the views of the European Union. -

Naturally Nola | Television Academy

H O M AE W A R ND ES W S & P H O T VO I SD E EO VS E N A T CS A D EF MO YU N D AA TR I CO HN I V E S M E M B E R S M A G A Z I N E IN THE April 07, 2017 MIX NaturayllN oal Dewanda Wise waited 30 years to play the part she was apparently born to play. Randee Dawn Rowan Daly Here’s what made DeWanda Wise decide to watch Spike Lee’s classic 1986 film, She’s Gotta Have It: A few years ago, a NEWS boyfriend gave her a DVD and said, “You remind me of Nola Darling.” Announcing the New Choreography Peer Turns out that her boyfriend was either a casting director in the making Group or prescient, because Wise is playing Nola, the free-spirited young Brooklynite in the Netflix 10-part series of the same name, adapted, executive-produced and directed by Lee himself. The Academy Remembers Florence Wise was “blown away” by the original film — “I remember thinking how Henderson bold and ahead of its time it was” — but she’s a little in the dark about how the TV version, which she says Lee approaches like a 10-part movie, will progress. “It’s a very large trust issue,” she says. Florence Henderson: A Though the Baltimore native has been racking up credits for more than Superior Mother a decade in films and on TV, she’s especially busy lately. -

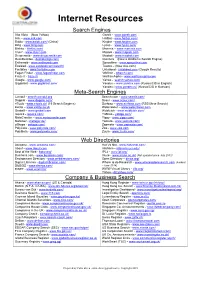

Internet Resources

Internet Resources Search Engines Alta Vista – (Now Yahoo) Gseek - www.gseek.com Ask – www.ask.com HotBot - www.hotbot.com/ Baidu - www.baidu.com/ (China) Kngine - www.kngine.com Bing - www.bing.com Lycos - www.lycos.com/ Blekko - blekko.com/ Mamma – www.mamma.com Cluuz - www.cluuz.com Mojeek - www.mojeek.com Deeperweb - www.deeperweb.com Mozbot - www.mozbot.com DuckDuckGo - duckduckgo.com/ Quintura – (Now a children’s Search Engine) Entireweb - www.entireweb.com Spacetime - www.spacetime.com Exalead - www.exalead.com/search/ Teoma – (Now Ask.com) Factbites - www.factbites.com Untabbed - untabbed.com (Google Results) Fagan Finder - www.faganfinder.com WbSrch - wbsrch.com/ Fraze It - fraze.it/ WolframAlpha - www.wolframalpha.com Google - www.google.com/ Yahoo - search.yahoo.com/ Gigablast - www.gigablast.com/ Yandex – www.yandex.com (Russia/CIS in English) Yandex - www.yandex.ru/ (Russia/CIS in Russian) Meta-Search Engines Carrot2 - search.carrot2.org Search.com - www.search.com/ Dogpile - www.dogpile.com/ Scour - www.scour.com/ eTools - www.etools.ch/ (15 Search Engines) Surfwax – www.surfwax.com (RSS Meta-Search) Excite – www.excite.co.uk Webcrawler – www.webcrawler.com Graball – www.graball.com Webfetch - www.webfetch.com/ Ixquick - ixquick.com/ YaBiGo - yabigo.com/ MetaCrawler – www.metacrawler.com Yippy - www.yippy.com/ MetaGer - metager.de/ Yometa - www.yometa.com/ oSkope - oskope.com/ Zapmeta - www.zapmeta.com/ PolyCola - www.polycola.com/ Zoo - www.zoo.com PolyMeta - www.polymeta.com/ Zuula - www.zuula.com/ Web Directories Accoona