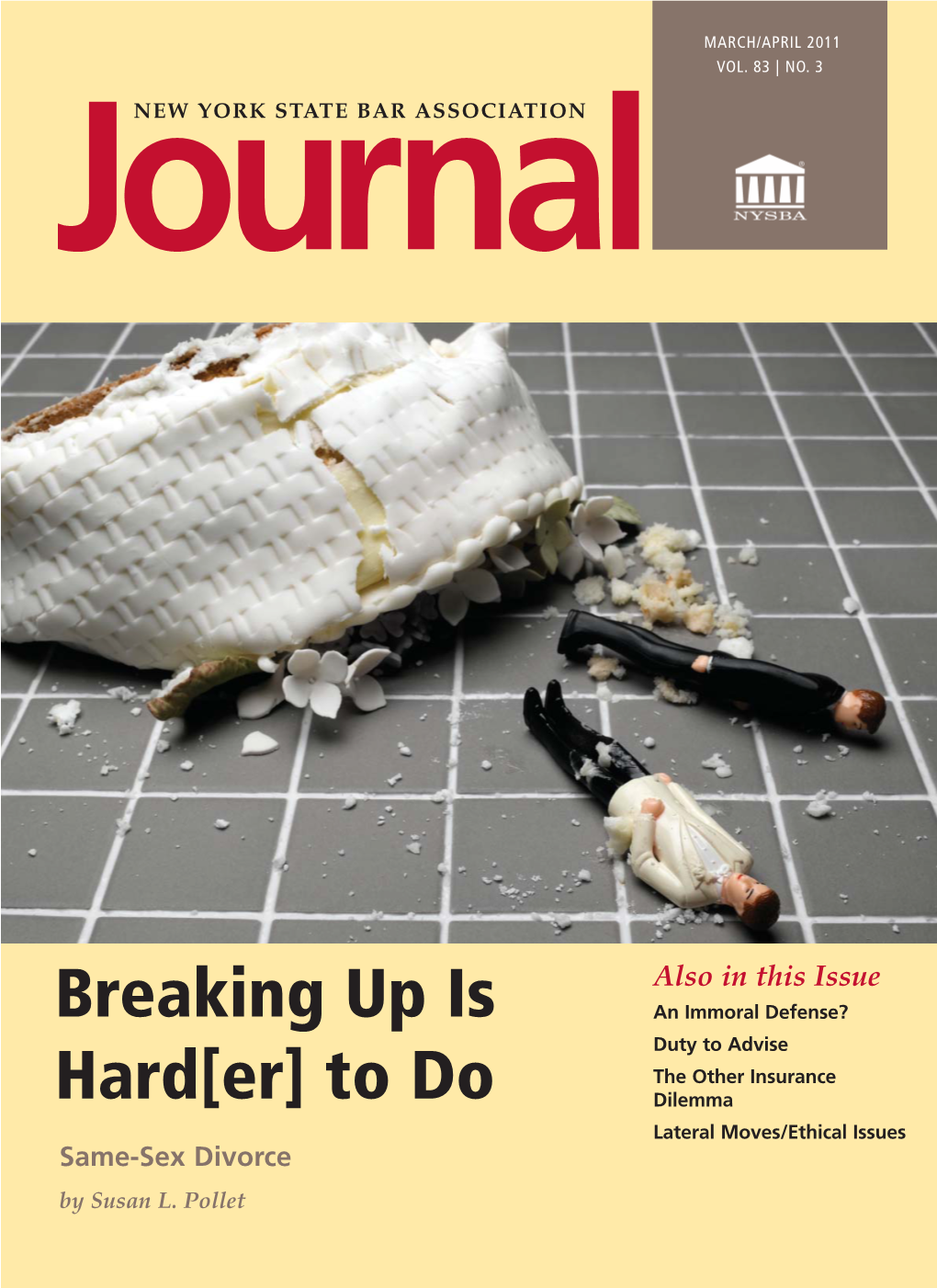

March/April 2011 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

FAR-FLUNG LEADERS Business on a Global Scale Opens the Door to Extraordinary Careers

THE MAGAZINE OF THE HAAS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Summer 2013 3 TEE TIME 14 OB GAME CHANGER 20 BUILDING WORK-LIFE BALANCE Haas undergrad Michael Weaver becomes the Prof. Barry Staw has far-reaching infl uence on Real estate developer Carol Meyer encourages fi rst current Cal golfer to make the Masters the fi eld of organizational behavior women to pay it forward FAR-FLUNG LEADERS Business on a global scale opens the door to extraordinary careers Supreme Energy CEO Supramu Santosa, BS 80, MBA 81, at his company’s geothermal plant in Indonesia The Berkeley-Haas Advantage Step outside of your day-to-day and return to one of the most stimulating business environments in the world. UPCOMING PROGRAMS The Art of the Pitch September 16-17, 2013 Product Management September 23-27, 2013 Berkeley Executive Leadership Program September 30-October 4, 2013 Women’s Executive Leadership Program October 4-17, 2013 Financial Analysis for Non-Financial Executives October 21-25, 2013 Corporate Business Model Innovation October 28-29, 2013 All Berkeley-Haas alumni enjoy special pricing for open-enrollment programs. Find the right opportunity for you; contact: Kristina Susac, Director of Marketing and Open Programs +1.510.642.9167 | [email protected] www.executive.berkeley.edu Summer 2013 FEATURES AND DEPARTMENTS The International Issue EDITOR IN CHIEF Ronna Kelly, BS 92 UP FRONT EXECUTIVE EDITORS Richard Kurovsky Ute Frey DESIGN Cuttriss & Hambleton, Berkeley STAFF WRITERS Valerie Gilbert, Amy Marcott, Pamela Tom CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Victoria Chang, Mandy 2 Haas List Erickson, Kim Girard, Moira A newly remodeled Haas Muldoon, Christine Rohan, courtyard comes alive. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Spring 2017 • May 7, 2017 • 12 P.M

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 415TH COMMENCEMENT SPRING 2017 • MAY 7, 2017 • 12 P.M. • OHIO STADIUM Presiding Officer Commencement Address Conferring of Degrees in Course Michael V. Drake Abigail S. Wexner Colleges presented by President Bruce A. McPheron Student Speaker Executive Vice President and Provost Prelude—11:30 a.m. Gerard C. Basalla to 12 p.m. Class of 2017 Welcome to New Alumni The Ohio State University James E. Smith Wind Symphony Conferring of Senior Vice President of Alumni Relations Russel C. Mikkelson, Conductor Honorary Degrees President and CEO Recipients presented by The Ohio State University Alumni Association, Inc. Welcome Alex Shumate, Chair Javaune Adams-Gaston Board of Trustees Senior Vice President for Student Life Alma Mater—Carmen Ohio Charles F. Bolden Jr. Graduates and guests led by Doctor of Public Administration Processional Daina A. Robinson Abigail S. Wexner Oh! Come let’s sing Ohio’s praise, Doctor of Public Service National Anthem And songs to Alma Mater raise; Graduates and guests led by While our hearts rebounding thrill, Daina A. Robinson Conferring of Distinguished Class of 2017 Service Awards With joy which death alone can still. Recipients presented by Summer’s heat or winter’s cold, Invocation Alex Shumate The seasons pass, the years will roll; Imani Jones Lucy Shelton Caswell Time and change will surely show Manager How firm thy friendship—O-hi-o! Department of Chaplaincy and Clinical Richard S. Stoddard Pastoral Education Awarding of Diplomas Wexner Medical Center Excerpts from the commencement ceremony will be broadcast on WOSU-TV, Channel 34, on Monday, May 8, at 5:30 p.m. -

GRANDPA "Pilot" 1/21/15 by Daniel Chun ©2015, ABC Studios. All

GRANDPA "Pilot" 1/21/15 by Daniel Chun ©2015, ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. Grandpa 1. COLD OPEN INT. A DIMLY-LIT ROOM - NIGHT CLOSE UP on JIMMY’s handsome face, with the eyes and the hair and the sexy everything. JAZZY music plays faintly underneath. Jimmy stares right at camera - intense, smoldering, searching. JIMMY Hah! There you are, you little bastard. REVEAL that he’s looking in the mirror of a men’s room. He finds and plucks a grey hair from the middle of his head. He checks himself out again and smiles: perfect. He walks out. Note - the following is an evolving master shot using a combination of motion control and time lapse. It’s like the guy who shot Birdman had sex with the guy who shot the Steve Carell motion control shot in Crazy Stupid Love and they had a baby that was this shot. The funniest, coolest, sexiest opening to a comedy pilot ever. No pressure. INT. JIMMY’S RESTAURANT - CONTINUOUS Jimmy walks down the hall toward the main dining room. The song gets louder and we hear the lyrics: ...and all the girls dreamed that they’d be your partner, they’d be your partner and--” “YOU’RE SO VAIN” plays as Jimmy strolls into his crowded, old- school-cool restaurant, Jimmy's. -

Board of Directors

HAWAII FOODBANK Board of Directors BOARD OFFICERS Mark Tonini Ashley Nagaoka Jason Haaksma Hawaii Foodservice Alliance Hawaii News Now Enterprise Holdings Jeff Moken Chair Jeff Vigilla Patrick Ono Michelle Hee Hawaiian Airlines Chef Point of View Matson Inc. ‘Iolani School Christina Hause James Wataru Tim Takeshita Ryan Hew First Vice Chair United Public Enterprise Holdings Hew and Bordenave LLP Kaiser Permanente Workers Union, AFSCME Local 646 Beth Tokioka Blake Ishizu David Herndon Kaua‘i Island Utility Hawaii Foodservice Second Vice Chair Jason Wong Cooperative Alliance Hawaii Medical Service Sysco Hawaii Association Sonia Topenio Crystine Ito Lauren Zirbel Bank of Hawaii Rainbow Drive-In James Starshak Hawaii Food Industry Secretary Association Laurie Yoshida Woo Ri Kim Community Volunteer Corteva Agriscience Girl Scouts of Hawai‘i EXECUTIVE Neill Char PARTNERS BOARD ALAKA‘I Reena Manalo Treasurer YOUNG LEADERS HDR Inc. First Hawaiian Bank Chuck Cotton iHeartMedia Toby Tamaye Del Mochizuki Ron Mizutani Chair UHA Health President & CEO Dennis Francis AT Marketing LLC Insurance Hawaii Foodbank Honolulu Star-Advertiser Hannah Hyun Nicole Monton BOARD OF DIRECTORS D.K. Kodama Marketing Committee MidWeek D.K. Restaurants Chair Scott Gamble Good Swell Inc. Jay Park LH Gamble Co. Katie Pickman Park Communications Hawaii News Now Christina Morisato Terri Hansen-Shon Events Committee Chair Kelly Simek Terri Hansen & EMERITUS Hawaiian Humane Society KHON2 Associates Inc. ADVISORY BOARD Maile Au Randy Soriano Denise Hayashi Cindy Bauer University of Hawaii The RS Marketing Yamaguchi Surfing the Nations Foundation Group Hawaii Wine & Food Festival Jade Moon Kelsie N. Cajka Kai Takekawa Community Volunteer Blue Zones Project – Zephyr Insurance Peter Heilmann Hawaii Co. -

Byron Nagasako, Melissa Johnson, Steven Sano, Robin Martin, Aimee Sze, Barbara Lane, Shelly Koyanagi, Liane Voss, Karen Nishigata, Kayla Gurtiza

Moanalua High School School Community Council Meeting Minutes Thursday, April 11, 2019 Attendance: Byron Nagasako, Melissa Johnson, Steven Sano, Robin Martin, Aimee Sze, Barbara Lane, Shelly Koyanagi, Liane Voss, Karen Nishigata, Kayla Gurtiza Called to order by at 5:32 pm by SCC Chair Bryon Nagasako in the office conference room 1. Approval of the March 7, 2019 minutes a. There were no minutes taken as the SCC group moved to the Principal’s Forum in the Library 2. Student’s Report - a. MENE Thanks SA Promotion runs from now to April 24 - students write Thank You messages to teachers/staff b. Senior Prom @ Sheraton Waikiki c. SA Retreat March 24-25 to plan activities and themes for next year; no slogan yet--based on Super Heroes d. Music Department Banquet bids on sale Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday this week i. Saturday, May 18 @ Hilton Waikiki Beach e. April 24 Purple Up Day (Military) f. May 2 May Day in MoHS Gym @ 8:30 a.m. 3. Parent’s Report - Steven Sano a. Crosswalk - will wait for later agenda items b. GE- will wait for later agenda items c. Junior Prom - Students had a good time! 4. Teacher’s Report - Voss, Koyanagi, Lane, Sze a. April 5 - MoHS Annual PD Conference about 400+ in attendance b. April 10 - MoHS Performing Arts Center Groundbreaking Ceremony c. Testing i. April 9-12: Smarter Balanced Assessments (Grade 11) ii. April 29 - May 31: Biology EOC Assessment iii. May 6-17: AP Testing Begins d. Report Cards distributed in Homeroom this week (April 9-12) e. -

Board Elects 2015-2016 Officers on July 24, 2015, the Members of Professional Standards Committee

North Carolina State Board of Certified Public Accountant Examiners 1101 Oberlin Rd., Ste. 104 • PO Box 12827 • Raleigh, NC 27605 • 919-733-4222 • nccpaboard.gov • No. 02-201509-2015 Board Elects 2015-2016 Officers On July 24, 2015, the members of Professional Standards Committee. Truitt, one of two public members the Board elected officers for 2015- He is a member of the NCACPA and of the Board, has been a member of 2016. the AICPA. the Board since 2014 and has served The mid-term election was nec- Cook, who served on the Board as a member of the Professional Ed- essary because of changes in the 2009-2012 and was re-appointed ucation & Applications Committee. Board’s membership. in 2013, has served as Vice Presi- He is a partner with Smith, An- Unanimously elected to office were dent and Secretary-Treasurer of the derson, Blount, Dorsett, Mitchell & Michael H. Womble, CPA, President; Board. Jernigan, L.L.P. (Smith Anderson). Wm. Hunter Cook, CPA, Vice Presi- He has been a member of the Ex- dent; and Jeffrey J. Truitt, Esq., Sec- ecutive Committee, Professional Does the Board Have retary-Treasurer. Standards Committee, Audit Com- Your Correct Email Womble, the managing partner mittee, Personnel Committee, Pro- Address? of the CPA firm Williams Overman fessional Education & Applications 21 NCAC 08J .0107 requires Pierce, LLP, has been a member of Committee, and Communications licensees to notify the Board the Board since 2012. Committee. in writing within 30 days of any He previously served the Board Cook is a partner with Dixon change in contact information, in- as Vice President and as a member Hughes Goodman, LLP, and is a cluding email address. -

Sundance Institute Unveils Latest Episodic Story Lab Fellows

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: September 20, 2016 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Unveils Latest Episodic Story Lab Fellows 11 New Television Pilots Selected from 2,000 Submissions Projects Include Tudor-Era Family Comedy, Mysterious Antarctic Anomaly, Animated Greek Gods and More Rafael Agustin, Nilanjana Bose, Jakub Ciupinski, Mike Flynn, Eboni Freeman, Hilary Helding, Donald Joh; John McClain, Colin McLaughlin, Jeremy Nielsen, Connie O’Donahue, Calvin Lee Reeder, Marlena Rodriguez. Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced the 11 original projects selected for its third annual Episodic Story Lab. The spec pilots, which range from dystopian sci-fi to historical comedy, explore themes of personal and social identity, family dysfunction, political extremism, and the limits of human understanding. The Episodic Story Lab is the centerpiece of the Institute’s year-round support program for emerging television writers. During the Lab, the 13 selected writers (the “Fellows”) will participate in individual and group creative meetings, writers’ rooms, case study screenings, and pitch sessions to further develop their pilot scripts with guidance from accomplished showrunners, producers and television executives. Beginning with the Lab, Fellows will benefit from customized, ongoing support from Feature Film Program staff, Creative Advisors and Industry Mentors, led by Founding Director of the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program, Michelle Satter, and Senior Manager of the Episodic -

A Topical Approach to Argument

A TOPICAL APPROACH TO ARGUMENT: AN UN-ENLIGHTENED PARADIGM OF RHETORICAL INVENTION by THOMAS WILLIAM DUKE BETH S. BENNETT, COMMITTEE CHAIR ROBERT N. GAINES JASON EDWARD BLACK ALEXA S. CHILCUTT LUCAS P. NIILER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Communication and Information Science in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Thomas William Duke 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In contemporary society, expertise is often a liability for those seeking to persuade the public. This work argues that the contemporary rejection of expertise is caused by a lack of proper rhetorical training, that the lack of rhetorical training is in turn an effect of rhetorical pedagogies rooted in Enlightenment values, and finally that rhetoricians must return to a pre- Enlightenment pedagogy if expertise is ever to obtain the recognition it deserves. Contemporary rhetorical training in argument is examined through a discussion of the argument systems of Stephen Toulmin, Chaïm Perelman, and Aristotle. The important aspects of these argument systems, the Toulmin model of argument, Perelman’s universal audience, and the Aristotelian enthymeme, are reviewed and critiqued. In the latter portion of the work, the study describes a distinctly rhetorical method for inventing arguments and discusses its implications for the problem of popularizing expertise. ii DEDICATION I prepared this work for my own edification and understanding of the questions to which I hope it provides some answers. I hope that others may find some value in this rather public attempt to write my way to clarity. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

The Mid-America Adventist Outlook for 1987

"It is of the Lord's mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not. They are new every morning: great is thy faithfulness." Lamentations 3:22, 23 * The President's Outlook * Could It when his secretary informed him of the Pathfinders' plight. Otillook Surely, this is an unfortunate coinci- Official organ of the Mid-America Union Conference of Happen Here? dence, Janet said to herself as she dialed the Seventh-day Adventists, P.O. Box 6127 (8550 Pioneers number of a third denominational worker. Blvd.), Lincoln, NE 68506. (402) 483-4451. But once more she received a less-than- sympathetic reply. Editor James L. Fly Assistant Editor Shirley B. Engel Desperate, she phoned the youth director Typesetter Cheri Winters of her conference in a nearby state. "I will Printer Christian Record Braille Foundation try to phone some workers that I know in that area. And in the meantime, you'd better Change of address: Give your new address with zip code and include your name and old address as it appeared on keep trying some more too," he said. previous issues. (If possible clip your name and address One pastor the youth director called told from an old OUTLOOK.) him, "Look, our football team is whipping the britches off your boys. Give me another News from local churches and schools for publication in the OUTLOOK must be submitted through the local hour and maybe I can help then. So long old conference Communication Department, not directly to buddy," said the pastor. the OUTLOOK office. Between them, Janet and the youth director spent five hours calling ten church Mid-America Union Directory workers but in every case they were President J 0.