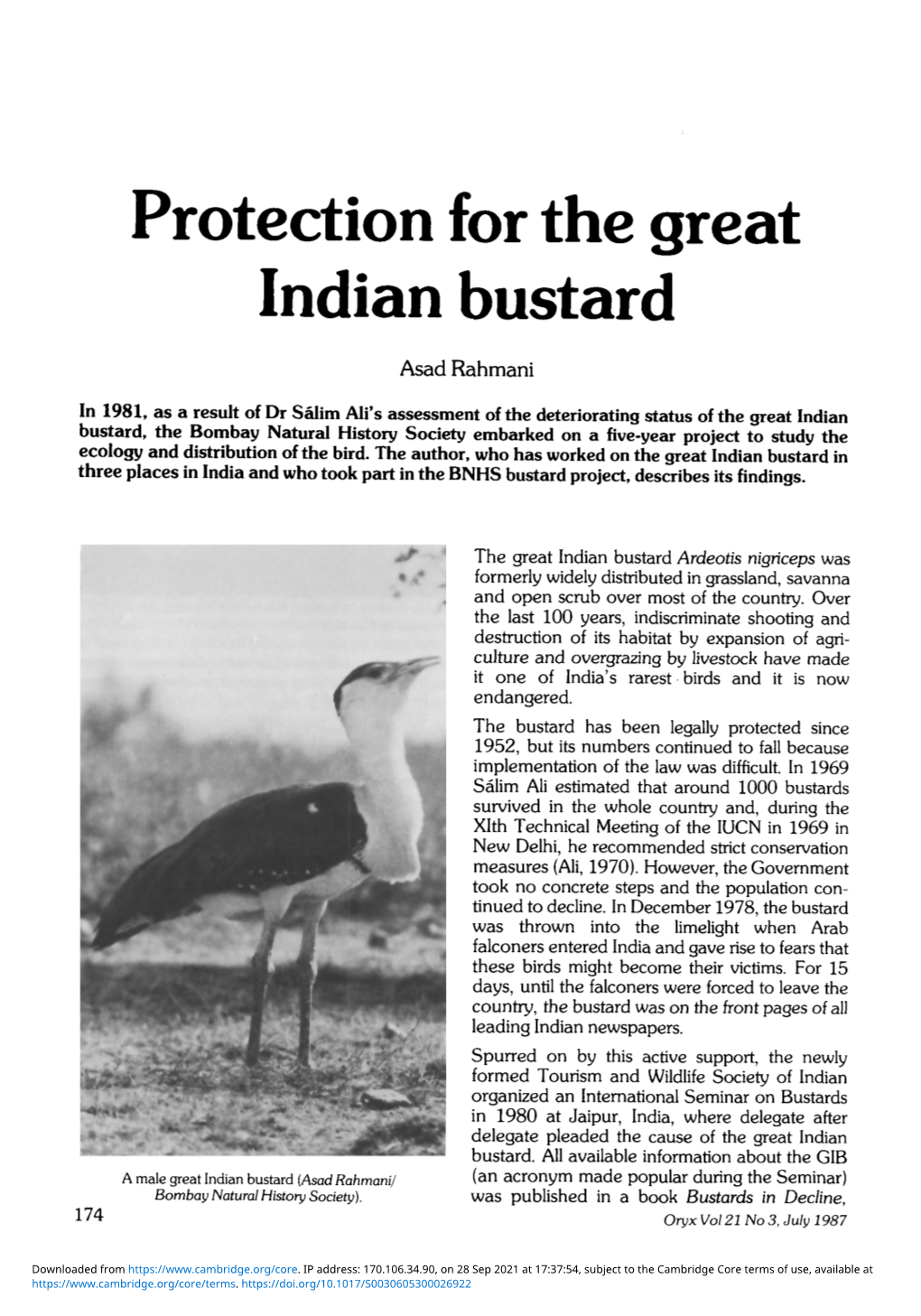

Protection for the Great Indian Bustard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

A Description of Copulation in the Kori Bustard J Ardeotis Kori

i David C. Lahti & Robert B. Payne 125 Bull. B.O.C. 2003 123(2) van Someren, V. G. L. 1918. A further contribution to the ornithology of Uganda (West Elgon and district). Novitates Zoologicae 25: 263-290. van Someren, V. G. L. 1922. Notes on the birds of East Africa. Novitates Zoologicae 29: 1-246. Sorenson, M. D. & Payne, R. B. 2001. A single ancient origin of brood parasitism in African finches: ,' implications for host-parasite coevolution. Evolution 55: 2550-2567. 1 Stevenson, T. & Fanshawe, J. 2002. Field guide to the birds of East Africa. T. & A. D. Poyser, London. Sushkin, P. P. 1927. On the anatomy and classification of the weaver-birds. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 57: 1-32. Vernon, C. J. 1964. The breeding of the Cuckoo-weaver (Anomalospiza imberbis (Cabanis)) in southern Rhodesia. Ostrich 35: 260-263. Williams, J. G. & Keith, G. S. 1962. A contribution to our knowledge of the Parasitic Weaver, Anomalospiza s imberbis. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 82: 141-142. Address: Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of " > Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. email: [email protected]. 1 © British Ornithologists' Club 2003 I A description of copulation in the Kori Bustard j Ardeotis kori struthiunculus \ by Sara Hallager Received 30 May 2002 i Bustards are an Old World family with 25 species in 6 genera (Johnsgard 1991). ? Medium to large ground-dwelling birds, they inhabit the open plains and semi-desert \ regions of Africa, Australia and Eurasia. The International Union for Conservation | of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Animals lists four f species of bustard as Endangered, one as Vulnerable and an additional six as Near- l Threatened, although some species have scarcely been studied and so their true I conservation status is unknown. -

The Bustards the Bustards

EndangeredEndangered BirdsBirds ofof BOTSWANA:BOTSWANA: TheThe BustardsBustards Commemorative Stamp Issue: August 2017 BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P5.00 P7.00 KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO Red-crested Korhaan & Black-Bellied Bustard Northern Black Korhaan BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P9.00 P10.00 O R O B N E A G KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO 0 7 BALOI KATLEGO 1 . 0 8 . 1 Denham’s Bustard Ludwig’s Bustard Endangered Birds of Botswana THE BUSTARDS ORDER: Otidiformes FAMILY: Otididae Bustards are large terrestrial birds mainly associated with dry open country and steppes in the Old World. They are omnivorous and nest on the ground. They walk steadily on strong legs and big toes, pecking for food as they go. They have long broad wings with “fingered” wingtips and striking patterns in flight. Many have interesting mating displays. (source: Wikipedia) DID YOU KNOW? The national bird of Botswana is the Kori Bustard KGORI /KORI BUSTARD/ Ardeotis kori and Chick Kori Bustard B 50t Botswana’s national bird. These bustards are the O largest and heaviest of the worlds’ flying birds. T S Found in open treeless areas throughout Botswana, W A they unfortunately have become scarce outside N protected areas, largely because people still kill A KATLEGO BALOI them to eat, despite it being illegal to hunt Kori Bustards in Botswana. They walk over the ground with long strides rather than to fly; indeed, results of satellite tracking in Central Kalahari Game Reserve showed most birds hardly moved beyond a 20 km radius in 2 years! (NO SPECIFIC SETSWANA NAME)/BLACK-BELLIED BOTSWANA KOORHAN/ Lissotis melanogaster P5.00 This bustard is found only in northern Botswana. -

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis Tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025 IUCN Bustard Specialist Group About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature- based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation was opened in October 2001 with the core support of the Spanish Ministry of Environment, the regional Government of Junta de Andalucía and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). The mission of IUCN-Med is to influence, encourage and assist Mediterranean societies to conserve and sustainably use natural resources in the region, working with IUCN members and cooperating with all those sharing the same objectives of IUCN. www.iucn.org/mediterranean About the IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of 9,000 experts. -

Status, Threats and Conservation of the Great

RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS assuring high pollen availability to the A-line plants till aphrodisiac value, the species is close to extinction from their peak flowering. its native haunts. Therefore, investigative surveys were These results verify our earlier findings1 in case of hy- done in its potential areas in Cholistan. Forty-four per- brid seed production of KBSH-1. A genotypic difference tinent people and 59 active hunting groups were inter- between the R line in these two hybrids did not show any viewed in order to assess the status of the species and the problems linked with its exploitation and conser- difference in flowering in response to similar treatments. vation. The results revealed that the population is on a Hastening of flowering following GA3 treatment to the 2 3 continuous decline. In about four years, nearly 49 out seeds in sorghum and rice , and nitrogen to pearl millet of 63 birds sighted were killed. The bird is under in- 4 and sorghum was reported. Hydration of seeds before tense pressure of human persecution and trade. The sowing had preponed flowering in maize variety5 and pa- study further highlights the implications needed to re- rental lines of hybrid, Sartaj6. Therefore, it can also be verse the fast extinction rate of the GIB from the concluded that seed priming with GA3 and application of province in particular and the country in general. urea (1%) as spray can be recommended as an effective technology for manipulation (preponement) of flowering Keywords: Conservation, Great Indian Bustard, status, of late parent to achieve perfect synchrony for economic threat. -

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: an Overview

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: An Overview SWARNDEEP S. HUNDAL Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, 141 004, India, email [email protected] Key Words: wildlife management, wildlife conservation, species recovery, blackbuck, Indian antelope, Antilope cervicapra, royal Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris, gangetic gharial, Gavialis gangeticus, great Indian bustard, Ardeotis nigriceps, India Introduction Wildlife resources constitute a vital link in the survival of the human species and have been a subject of much fascination, interest, and research all over the world. Today, when wildlife habitats are under severe pressure and a large number of species of wild fauna have become endangered, the effective conservation of wild animals is of great significance. Because every one of us depends on plants and animals for all vital components of our welfare, it is more than a matter of convenience that they continue to exist; it is a matter of life and death. Being living units of the ecosystem, plants and animals contribute to human welfare by providing • material benefit to human life; • knowledge about genetic resources and their preservation; and • significant contributions to the enjoyment of life (e.g., recreation). Human society depends on genetic resources for virtually all of its food; nearly half of its medicines; much of its clothing; in some regions, all of its fuel and building materials; and part of its mental and spiritual welfare. Considering the way we are galloping ahead, oblivious of what legacy we plan to leave for future generations, the future does not seem too bright. Statisticians have projected that by 2020, the human population will have increased by more than half, and the arable fertile land and tropical forests will be less than half of what they are today. -

Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18

Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 District: Kutch Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Collector Office Disaster Management Cell Kutch – Bhuj Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2016-17 Name of District : KUTCH Name of Collector : ……………………IAS Date of Update plan : June- 2017 Signature of District Collector : _______________________ INDEX Sr. No. Detail Page No. 1 Chapter-1 Introduction 1 1.01 Introduction 1 1.02 What is Disaster 1 1.03 Aims & Objective of plan 2 1.04 Scope of the plan 2 1.05 Evolution of the plan 3 1.06 Authority and Responsibility 3 1.07 Role and responsibility 5 1.08 Approach to Disaster Management 6 1.09 Warning, Relief and Recovery 6 1.10 Mitigation, Prevention and Preparedness 6 1.11 Finance 7 1.12 Disaster Risk Management Cycle 8 1.13 District Profile 9 1.14 Area and Administration 9 1.15 Climate 10 1.16 River and Dam 11 1.17 Port and fisheries 11 1.18 Salt work 11 1.19 Live stock 11 1.20 Industries 11 1.21 Road and Railway 11 1.22 Health and Education 12 2 Chapter-2 Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment 13 2.01 Kutch District past Disaster 13 2.02 Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment of Kutch district 14 2.03 Interim Guidance and Risk & Vulnerability Ranking Analysis 15 2.04 Assign the Probability Rating 15 2.05 Assign the Impact Rating 16 2.06 Assign the Vulnerability 16 2.07 Ranking Methodology of HRVA 17 2.08 Identify Areas with Highest Vulnerability 18 2.09 Outcome 18 2.10 Hazard Analysis 18 2.11 Earthquake 19 2.12 Flood 19 2.13 Cyclone 20 2.14 Chemical Disaster 20 2.15 Tsunami 20 2.16 Epidemics 21 2.17 Drought 21 2.18 Fire 21 Sr. -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

Habitat Use by the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis Nigriceps (Gruiformes: Otididae) in Breeding and Non-Breeding Seasons

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 February 2013 | 5(2): 3654–3660 Habitat use by the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps (Gruiformes: Otididae) in breeding and non-breeding seasons in Kachchh, Gujarat, India ISSN Short Communication Short Online 0974-7907 Sandeep B. Munjpara 1, C.N. Pandey 2 & B. Jethva 3 Print 0974-7893 1 Junior Research Fellow, 3 Scientist, GEER Foundation, Indroda Nature Park, P.O. Sector-7, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, OPEN ACCESS India 2 Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, Sector-10, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, India 3 Presently address: Green Support Services, C-101, Sarthak Apartment, Kh-0, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Abstract: The Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps, a threatened District (Pandey et al. 2009; Munjpara et al. 2011). and endemic species of the Indian subcontinent, is declining in its natural habitats. The Great Indian Bustard is a bird of open land and In order to develop effective conservation strategies was observed using the grasslands habitat (73%), followed by areas for the long term survival of GIB, it is important to covered with Prosopis (11%). In the grasslands, the communities know its detailed habitat requirements. Determination dominated with Cymbopogon martinii were utilized the highest, while those dominated by Aristida adenemsoidis were least utilized. of various habitats and their utility by the species was As Cymbopogon martinii is non-palatable, we infer that it does not carried out to understand whether the grassland is attract livestock and herdsmen resulting in minimum movement and sufficient enough for detailed management planning. -

Alexander 2013 Principles-Of-Animal-Locomotion.Pdf

.................................................... Principles of Animal Locomotion Principles of Animal Locomotion ..................................................... R. McNeill Alexander PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2003 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2006 Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12634-0 Paperback ISBN-10: 0-691-12634-8 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Alexander, R. McNeill. Principles of animal locomotion / R. McNeill Alexander. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-691-08678-8 (alk. paper) 1. Animal locomotion. I. Title. QP301.A2963 2002 591.47′9—dc21 2002016904 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Galliard and Bulmer Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ pup.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1098765432 Contents ............................................................... PREFACE ix Chapter 1. The Best Way to Travel 1 1.1. Fitness 1 1.2. Speed 2 1.3. Acceleration and Maneuverability 2 1.4. Endurance 4 1.5. Economy of Energy 7 1.6. Stability 8 1.7. Compromises 9 1.8. Constraints 9 1.9. Optimization Theory 10 1.10. Gaits 12 Chapter 2. Muscle, the Motor 15 2.1. How Muscles Exert Force 15 2.2. Shortening and Lengthening Muscle 22 2.3. Power Output of Muscles 26 2.4. Pennation Patterns and Moment Arms 28 2.5. Power Consumption 31 2.6. Some Other Types of Muscle 34 Chapter 3. -

Lesser Florican Sypheotides Indica in Warora (Chandrapur, Maharashtra, India): Conservation Requirements Sujit S

50 Indian BIRDS VOL. 10 NO. 2 (PUBL. 20 JUNE 2015) Streaked Wren Babbler Turdinus brevicaudatus Chestnut-tailed Starling Sturnia malabarica Nepal Tit Babbler Alcippe nipalensis Common Myna Acridotheres tristis Spot-breasted Laughing-thrush Garrulax merulinus Oriental Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis White-crested Laughing-thrush G. leucolophus White-rumped Shama Kittacincla malabarica Blue-winged Laughing-thrush Trochalopteron squamatum Pale-chinned Blue Flycatcher Cyornis poliogenys Chestnut-crowned Laughing-thrush T. erythrocephalum Rufous-bellied Niltava Niltava sundara Grey Sibia Heterophasia gracilis Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophris Silver-eared Mesia Leiothrix argentauris White-tailed Robin Myiomela leucura Rufous-backed Sibia Leioptila annectens Golden Bush Robin Tarsiger chrysaeus Red-faced Liocichla Liocichla phoenicea Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicilla Streak-throated Barwing Sibia waldeni Snowy-browed Flycatcher F. hyperythra Blue-winged Minla Siva cyanouroptera Rufous-gorgetted Flycatcher F. strophiata Rusty-fronted Barwing Actinodura egertoni Sapphire Flycatcher F. sapphira Beautiful Nuthatch Sitta formosa Purple Cochoa Cochoa purpurea Lesser Florican Sypheotides indica in Warora (Chandrapur, Maharashtra, India): Conservation requirements Sujit S. Narwade, Vithoba Hegde, Vipin V. Fulzele, Bandu T. Lalsare & Asad R. Rahmani Narwade, S. S., Hegde, V., Fulzele, V. V., Lalsare, B. T., & Rahmani, A. R., 2015. Lesser Florican Sypheotides indica in Warora (Chandrapur, Maharashtra, India): Conservation requirements. Indian BIRDS 10 (2): 50–52. Sujit S. Narwade, Project Scientist, Bharat Natural History Society (BNHS-India), Hornbill House, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Road, Mumbai 400001, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: [email protected].[Corresponding author] Vithoba Hegde, Senior Field Assistant, Collection Department, Bharat Natural History Society (BNHS-India), Hornbill House, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Road, Mumbai 400001, Maharashtra, India. Vipin V. Fulzele, Warora, Chandrapur, Maharashtra, India. -

Ghana Included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

IDENTIFICATION GUIDE The Species of Ghana Included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) YEAR 2018 IDENTIFICATION GUIDE The CITES Species of Ghana Born Free USA thanks the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for funding this guide and the Ghana authorities for their support. See the last section for a list of useful contacts, including the organizations displayed above. PHOTOS: MICHAEL HEYNS, BROCKEN INAGLORY, GEORGE CHERNILEVSKY, ALEX CHERNIKH, HANS HILLEWAERT, DAVID D’O, JAKOB FAHR TABLE OF CONTENTS How to use this guide ..........................................1 CHORDATA / ELASMOBRANCHII What is CITES? ..............................................3 / Carcharhiniformes ........................................101 What is the IUCN Red List? .....................................10 / Lamniformes .............................................101 How to read this guide ........................................13 / Orectolobiformes .........................................102 What the IUCN colors mean ....................................15 / Pristiformes ..............................................103 Steps for CITES permits .......................................17 Presentation of shark and ray species listed in CITES in West Africa ........19 CHORDATA / ACTINOPTERI / Syngnathiformes ..........................................103 CHORDATA / MAMMALIA / Artiodactyla ..............................................51 ARTHROPODA / ARACHNIDA / Carnivora ................................................53