Running out of Time? the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis Nigriceps—Status, Viability, and Conservation Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing Extinction Programme of Birdlife International

Draft of final report - Prevention of Extinction Programme - BirdLife International Status survey of Lesser Florican Sypheotides indicus for preparation of site wise conservation plan Final report November 2017 1 | P a g e Draft of final report - Prevention of Extinction Programme - BirdLife International Status survey of Lesser Florican Sypheotides indicus for preparation of sitewise conservation plan Final Report November 2017 Principal Investigator Dr. Deepak Apte Co- Principal Investigator Dr. Sujit Narwade Senior Scientist Dr. Girish Jathar Scientists Biswajit Chakdar Ngulkholal Khongsai Research Fellows Ameya Karulkar Balasaheb Lambture 2 | P a g e Draft of final report - Prevention of Extinction Programme - BirdLife International Recommended citation Narwade, S.S., Karulkar, A.K., Lambture, B.R., Chakdar, B., Khongsai, N., Jathar, G. and Apte, D. (2017): Status survey of Lesser Florican Sypheotides indicus for preparation of site wise conservation plan. Report submitted by BNHS. Pp 30. BNHS Mission: Conservation of Nature, primarily Biological Diversity through action based on Research, Education and Public Awareness © BNHS 2017: All rights reserved. This publication shall not be reproduced either in full original part in any form, either in print or electronic or any other medium, without the prior written permission of the Bombay Natural History Society. Disclaimer: Google Earth Maps provided in the report are based on observations carried out by the BNHS team. Actual size and structure of the size may vary on ground. Adress -

(PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat

ROADS AND BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT (PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Under AIIB Loan Assistance May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Roads & Buildings Department (Panchayat), Environmental and Social Impact Government of Gujarat Assessment (ESIA) Report Table of Content 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 MUKHYA MANTRI GRAM SADAK YOJANA ................................................................ 1 1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT: GUJARAT .................................... 3 1.3.1 Population Profile ........................................................................................ 5 1.3.2 Social Characteristics ................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Distribution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population ................. 5 1.3.4 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................ 5 1.3.5 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................... 6 1.3.6 Agriculture Base .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.7 Land use Pattern in Gujarat ......................................................................... -

A Description of Copulation in the Kori Bustard J Ardeotis Kori

i David C. Lahti & Robert B. Payne 125 Bull. B.O.C. 2003 123(2) van Someren, V. G. L. 1918. A further contribution to the ornithology of Uganda (West Elgon and district). Novitates Zoologicae 25: 263-290. van Someren, V. G. L. 1922. Notes on the birds of East Africa. Novitates Zoologicae 29: 1-246. Sorenson, M. D. & Payne, R. B. 2001. A single ancient origin of brood parasitism in African finches: ,' implications for host-parasite coevolution. Evolution 55: 2550-2567. 1 Stevenson, T. & Fanshawe, J. 2002. Field guide to the birds of East Africa. T. & A. D. Poyser, London. Sushkin, P. P. 1927. On the anatomy and classification of the weaver-birds. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 57: 1-32. Vernon, C. J. 1964. The breeding of the Cuckoo-weaver (Anomalospiza imberbis (Cabanis)) in southern Rhodesia. Ostrich 35: 260-263. Williams, J. G. & Keith, G. S. 1962. A contribution to our knowledge of the Parasitic Weaver, Anomalospiza s imberbis. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 82: 141-142. Address: Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of " > Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. email: [email protected]. 1 © British Ornithologists' Club 2003 I A description of copulation in the Kori Bustard j Ardeotis kori struthiunculus \ by Sara Hallager Received 30 May 2002 i Bustards are an Old World family with 25 species in 6 genera (Johnsgard 1991). ? Medium to large ground-dwelling birds, they inhabit the open plains and semi-desert \ regions of Africa, Australia and Eurasia. The International Union for Conservation | of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Animals lists four f species of bustard as Endangered, one as Vulnerable and an additional six as Near- l Threatened, although some species have scarcely been studied and so their true I conservation status is unknown. -

The Bustards the Bustards

EndangeredEndangered BirdsBirds ofof BOTSWANA:BOTSWANA: TheThe BustardsBustards Commemorative Stamp Issue: August 2017 BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P5.00 P7.00 KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO Red-crested Korhaan & Black-Bellied Bustard Northern Black Korhaan BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P9.00 P10.00 O R O B N E A G KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO 0 7 BALOI KATLEGO 1 . 0 8 . 1 Denham’s Bustard Ludwig’s Bustard Endangered Birds of Botswana THE BUSTARDS ORDER: Otidiformes FAMILY: Otididae Bustards are large terrestrial birds mainly associated with dry open country and steppes in the Old World. They are omnivorous and nest on the ground. They walk steadily on strong legs and big toes, pecking for food as they go. They have long broad wings with “fingered” wingtips and striking patterns in flight. Many have interesting mating displays. (source: Wikipedia) DID YOU KNOW? The national bird of Botswana is the Kori Bustard KGORI /KORI BUSTARD/ Ardeotis kori and Chick Kori Bustard B 50t Botswana’s national bird. These bustards are the O largest and heaviest of the worlds’ flying birds. T S Found in open treeless areas throughout Botswana, W A they unfortunately have become scarce outside N protected areas, largely because people still kill A KATLEGO BALOI them to eat, despite it being illegal to hunt Kori Bustards in Botswana. They walk over the ground with long strides rather than to fly; indeed, results of satellite tracking in Central Kalahari Game Reserve showed most birds hardly moved beyond a 20 km radius in 2 years! (NO SPECIFIC SETSWANA NAME)/BLACK-BELLIED BOTSWANA KOORHAN/ Lissotis melanogaster P5.00 This bustard is found only in northern Botswana. -

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis Tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025 IUCN Bustard Specialist Group About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature- based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation was opened in October 2001 with the core support of the Spanish Ministry of Environment, the regional Government of Junta de Andalucía and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). The mission of IUCN-Med is to influence, encourage and assist Mediterranean societies to conserve and sustainably use natural resources in the region, working with IUCN members and cooperating with all those sharing the same objectives of IUCN. www.iucn.org/mediterranean About the IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of 9,000 experts. -

![Chlamydotis [Undulata] Macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4010/chlamydotis-undulata-macqueenii-in-saudi-arabia-394010.webp)

Chlamydotis [Undulata] Macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia

7. Display behaviour of breeding male Asiatic houbara (Chlamydotis [undulata] macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia Abstract Male Asiatic houbara (Chlamydotis [undulata] macqueenii) give spectacular visual displays, which may function as truthful advertising of fitness, and allow females to choose suitable partners. I examined whether a pre-condition for female choice – variation in male display intensity – exists in a houbara population in Mahazat as-Sayd Reserve, west central Saudi Arabia. Five key behavioural components of displays from 12 known-age males were sampled regularly over three breeding seasons from 1996 to 1998. On 100 occasions, a total of 570 running displays, 497 inter-display periods, all occurrence of feather flashing displays and feeding, and the distance covered during displays, were recorded. In addition, previously unrecorded details on the pattern and timing of male displays, and interactions between displaying houbara and other houbara, and with other species were described. Males were ranked based on the intensity of each behaviour each year, and on a combined rank for all behaviours. Intensity of male display differed among males in all years for all behaviours except distance ran during displays in 1997. Some males consistently ranked highly for all behaviours and in all years, whereas other males gave long display runs with short inter-display periods, but covered very little distance. Two strategies for performing displays that vary in intensity are suggested. There was no clear relationship between display intensity and male age or experience: in some years, the youngest, most inexperienced males gave the most intense displays. I conclude that the prediction that males vary in their display intensity was supported, and this allows opportunities for future researchers to examine whether the highest ranked males gain more matings with females than do lower ranking males. -

Status, Threats and Conservation of the Great

RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS assuring high pollen availability to the A-line plants till aphrodisiac value, the species is close to extinction from their peak flowering. its native haunts. Therefore, investigative surveys were These results verify our earlier findings1 in case of hy- done in its potential areas in Cholistan. Forty-four per- brid seed production of KBSH-1. A genotypic difference tinent people and 59 active hunting groups were inter- between the R line in these two hybrids did not show any viewed in order to assess the status of the species and the problems linked with its exploitation and conser- difference in flowering in response to similar treatments. vation. The results revealed that the population is on a Hastening of flowering following GA3 treatment to the 2 3 continuous decline. In about four years, nearly 49 out seeds in sorghum and rice , and nitrogen to pearl millet of 63 birds sighted were killed. The bird is under in- 4 and sorghum was reported. Hydration of seeds before tense pressure of human persecution and trade. The sowing had preponed flowering in maize variety5 and pa- study further highlights the implications needed to re- rental lines of hybrid, Sartaj6. Therefore, it can also be verse the fast extinction rate of the GIB from the concluded that seed priming with GA3 and application of province in particular and the country in general. urea (1%) as spray can be recommended as an effective technology for manipulation (preponement) of flowering Keywords: Conservation, Great Indian Bustard, status, of late parent to achieve perfect synchrony for economic threat. -

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: an Overview

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: An Overview SWARNDEEP S. HUNDAL Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, 141 004, India, email [email protected] Key Words: wildlife management, wildlife conservation, species recovery, blackbuck, Indian antelope, Antilope cervicapra, royal Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris, gangetic gharial, Gavialis gangeticus, great Indian bustard, Ardeotis nigriceps, India Introduction Wildlife resources constitute a vital link in the survival of the human species and have been a subject of much fascination, interest, and research all over the world. Today, when wildlife habitats are under severe pressure and a large number of species of wild fauna have become endangered, the effective conservation of wild animals is of great significance. Because every one of us depends on plants and animals for all vital components of our welfare, it is more than a matter of convenience that they continue to exist; it is a matter of life and death. Being living units of the ecosystem, plants and animals contribute to human welfare by providing • material benefit to human life; • knowledge about genetic resources and their preservation; and • significant contributions to the enjoyment of life (e.g., recreation). Human society depends on genetic resources for virtually all of its food; nearly half of its medicines; much of its clothing; in some regions, all of its fuel and building materials; and part of its mental and spiritual welfare. Considering the way we are galloping ahead, oblivious of what legacy we plan to leave for future generations, the future does not seem too bright. Statisticians have projected that by 2020, the human population will have increased by more than half, and the arable fertile land and tropical forests will be less than half of what they are today. -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

Namibia & the Okavango

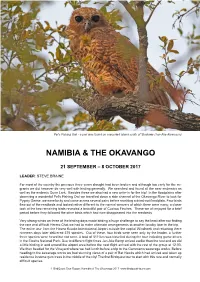

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Habitat Use by the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis Nigriceps (Gruiformes: Otididae) in Breeding and Non-Breeding Seasons

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 February 2013 | 5(2): 3654–3660 Habitat use by the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps (Gruiformes: Otididae) in breeding and non-breeding seasons in Kachchh, Gujarat, India ISSN Short Communication Short Online 0974-7907 Sandeep B. Munjpara 1, C.N. Pandey 2 & B. Jethva 3 Print 0974-7893 1 Junior Research Fellow, 3 Scientist, GEER Foundation, Indroda Nature Park, P.O. Sector-7, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, OPEN ACCESS India 2 Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, Sector-10, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, India 3 Presently address: Green Support Services, C-101, Sarthak Apartment, Kh-0, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382007, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Abstract: The Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps, a threatened District (Pandey et al. 2009; Munjpara et al. 2011). and endemic species of the Indian subcontinent, is declining in its natural habitats. The Great Indian Bustard is a bird of open land and In order to develop effective conservation strategies was observed using the grasslands habitat (73%), followed by areas for the long term survival of GIB, it is important to covered with Prosopis (11%). In the grasslands, the communities know its detailed habitat requirements. Determination dominated with Cymbopogon martinii were utilized the highest, while those dominated by Aristida adenemsoidis were least utilized. of various habitats and their utility by the species was As Cymbopogon martinii is non-palatable, we infer that it does not carried out to understand whether the grassland is attract livestock and herdsmen resulting in minimum movement and sufficient enough for detailed management planning. -

Biodiversity Observations

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: Amour McCarthy and Les G Underhill INTERNET SEARCHING OF BIRD–BIRD ASSOCIATIONS: A CASE OF BEE-EATERS HITCHHIKING LARGE AFRICAN BIRDS Peter Mikula & Piotr Tryjanowski Recommended citation format: Mikula P, Tryjanowski P. 2016. Internet searching of bird–bird associations: A case of bee-eaters hitchhiking large African birds. Biodiversity Observations 7.80: 1–6. URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=273 Published online: 17 November 2016 –