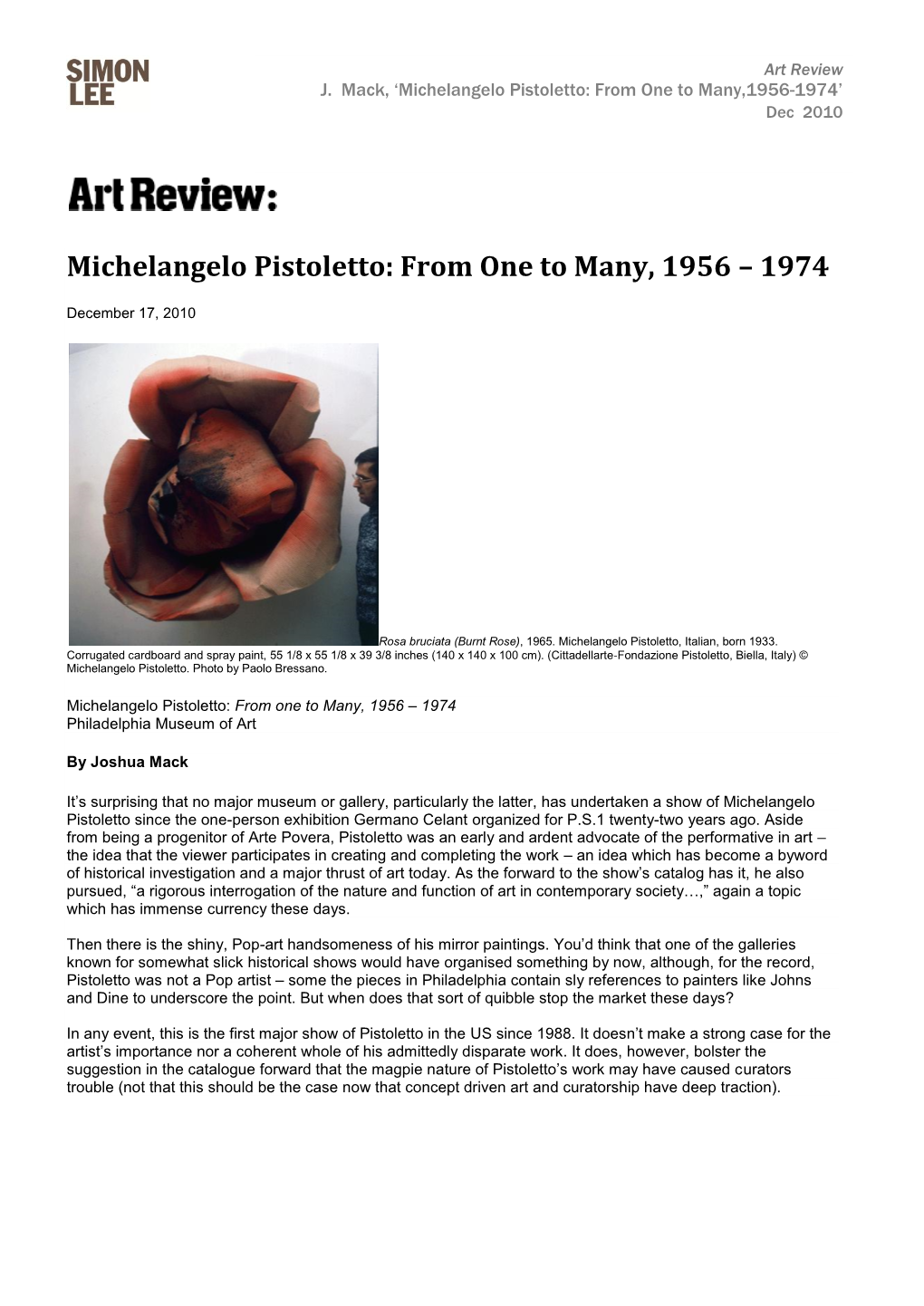

Michelangelo Pistoletto: from One to Many,1956-1974’ Dec 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release: Jose Dávila, Das Muss

Press Release: Jose Dávila, Das muss der Ort sein. Opening: September 6, 2013 at 6.00 pm, the artist will be present. Exhibition: September 7 through November 2, 2013. We inaugurate on September 6 during DC-Open Das muss der Ort sein (This Must Be the Place), our second exhibition with the Mexican artist Jose Dávila (born 1974 in Guadalajara, Mexico). It is his first exhibition in the Rhineland. We are glad to show five sculptures and three of his Cut-outs. Cut-outs are works for which Dávila cuts away the central objects from enlarged re- productions of iconic architectures or artworks in order to induce our imagination or cultural memory to complete the images. By framing these images (or what remains of them) between two sheets of glass, a new spatial image is created in particular by the voids. Because there is a shadow cast on the back of the frame. One could say: the depicted object leaves, a new object comes. In our current exhibition the removed objects are artworks from the last 60 years, that is, sculptures and installations by Giovanni Anselmo, Joseph Beuys, Marcel Broodthaers, Alexander Calder, Anthony Caro, Liam Gillick, Michael Heizer, Norbert Kricke, Richard Long, Walter de Maria, Cildo Meireless, Bruce Nauman, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Richard Serra or Tony Smith. Many of these works belong to the canon of art history. Even if we do not immediately know who was the author of the removed object, we feel – as a knowledgeable viewer – that we know the works and that we have them in our mind's eye. -

An Analysis from the Perspective of Artistic Intent Versus Audience Experience and Interpretation

. Volume 18, Issue 1 May 2021 The representation of audiences after 1960: An analysis from the perspective of artistic intent versus audience experience and interpretation Patrick Van Rossem, Utrecht University, The Netherlands Abstract: In The representation of the audiences after 1960, the question is asked whether we can consider the representation of the audience after 1960 in relation to artists’ ideas on the presence of an audience and its meaning giving activity. The focus is both on the representation of individual audience members or participants as well as on visitor groups. Since the 1960s the audience for art has grown and museums have seen their attendance rise. It has led amongst others to a more sophisticated mediation between artwork and audience. Since the 1960s one can also observe an increased awareness amongst artists of the fact that the experience of art and the attribution of meaning to art is differential in nature. But have artists accepted this reality? And can they ever come to terms with a critical art mediation that invites audiences to relate to art more subjectively? Analyses of both the representation of audiences and artists’ ideas on the presence of the audience shows that artists have been and are sometimes still struggling with these issues. In recent times however we can detect a growing acceptance of a more free and personal interpretation of art by the audience. Artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, Dan Graham, Bruce Nauman, Thomas Struth, Rineke Dijkstra, and Sophie Calle have represented audiences in ways that reveal their – positive, negative, worrying… - attitudes towards the presence of an interpreting, art consuming, desiring audience. -

Art in the Mirror: Reflection in the Work of Rauschenberg, Richter, Graham and Smithson

ART IN THE MIRROR: REFLECTION IN THE WORK OF RAUSCHENBERG, RICHTER, GRAHAM AND SMITHSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Eileen R. Doyle, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Stephen Melville, Advisor Professor Lisa Florman ______________________________ Professor Myroslava Mudrak Advisor History of Art Graduate Program Copyright by Eileen Reilly Doyle 2004 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation considers the proliferation of mirrors and reflective materials in art since the sixties through four case studies. By analyzing the mirrored and reflective work of Robert Rauschenberg, Gerhard Richter, Dan Graham and Robert Smithson within the context of the artists' larger oeuvre and also the theoretical and self-reflective writing that surrounds each artist’s work, the relationship between the wide use of industrially-produced materials and the French theory that dominated artistic discourse for the past thirty years becomes clear. Chapter 2 examines the work of Robert Rauschenberg, noting his early interest in engaging the viewer’s body in his work—a practice that became standard with the rise of Minimalism and after. Additionally, the theoretical writing the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty provides insight into the link between art as a mirroring practice and a physically engaged viewer. Chapter 3 considers the questions of medium and genre as they arose in the wake of Minimalism, using the mirrors and photo-based paintings of Gerhard Richter as its focus. It also addresses the particular way that Richter weaves the motifs and concerns of traditional painting into a rhetoric of the death of painting which strongly implicates the mirror, ultimately opening up Richter’s career to a psychoanalytic reading drawing its force from Jacques Lacan’s writing on the formation of the subject. -

ENGLISH - the Blueproject Foundation Wants to Thank Their Kindness to the Artist Michelangelo Pistoletto and His Wife Maria Pioppi and the Staff of Galleria Continua

- ENGLISH - The Blueproject Foundation wants to thank their kindness to the artist Michelangelo Pistoletto and his wife Maria Pioppi and the staff of Galleria Continua. The Blueproject Foundation hosts the solo exhibition neighbourhood of La Ribera and El Born. of Michelangelo Pistoletto, which can be seen in Il Salotto from November 13th 2015 to March 27th 2016. On the other hand, the Blueproject Foundation is proud to offer an exclusive and unique conference, with free admission, by the famous The exhibition features a selection of works by the Italian artist held in the Auditorium of the Escola Massana on Friday famous Italian artist that comprise a career of almost November 13th. As a central element of the activities related to his solo forty years, from the mid-seventies until today, in exhibition, this conference is the perfect opportunity to better discover which he reflects on the perception of the self and the the thought and career of one of the most important living contemporary society to which we belong through everyday objects artists in the recent decades and precursor of the movement Arte Povera. like mirrors, used as an element of identification and turning them into artworks by themselves. These The conference is a perfect way for young art students, and the interested pieces are not only part of the history of a great creator public, to delve into some of the central topics developed by the art of but also the testimony of a key period in the history of Pistoletto such as the self-portrait, infinity, mirrors or the perception of contemporary art. -

Jorge Manuel Barreto Xavier Goa, India, November 6, 1965 Portuguese Nationality

Jorge Manuel Barreto Xavier Goa, India, November 6, 1965 Portuguese nationality Academic Qualifications • 5 years Degree in Law, juridical-political specialty, Faculty of Law, University of Lisbon with an average of 12/20 (2002). • Advanced Studies Diploma in Political Science, Political Science Department, Lisbon New University, with an average of 17/20 (2010). • PhD researcher of the PhD program in Public Policy at the Lisbon University Institute ISCTE-IUL. • Secondary Studies Diploma in Humanistic Studies High School Afonso de Albuquerque, Guarda, with an average of 17/20 (1984). Other Qualifications • Amsterdam Summer University programme ‘Arts management in a European changing context’ (1991). • Specialisation in Arts Management (National Institute of Administration - INA), under the supervision of Prof. Joan Jeffri, Director of the Arts Management program at Columbia University, with a final grade of ‘Very Good’ (1989). Functions Currently • Coordinator of the Programme Culture, Economy and Society, Institute of Public and Social Policy / Lisbon University Institute • Assistant Professor of Lisbon University Institute (ISCTE/IUL) since September 2011 • Associate Researcher of the Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology (CIES-ISCTE) Previously Public Service • Secretary of State for Culture to the Prime Minister of Portugal (2012–2015). Portuguese Government Member of the EU Council of Ministers of Culture (2012-2015). • Director General of Arts of the Ministry of Culture (2008–2010). • Director of the Cultural Development Fund (2008–2010). • Assistant to the Minister of Culture (2008). • Deputy Mayor of Oeiras, with the Responsibilities of Culture, Youth and Consumer Protection (2003–2005). • Member of the Board of Directors of the Portuguese Youth Institute, representing national youth associations (1999–2002). -

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 BOARD of TRUSTEES 5 Letter from the Chair

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 4 A STRATEGIC VISION FOR THE 6 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 48 Conserving 54 Supporting 60 Staffing and Volunteering 70 A CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 75 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 80 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 86 SUPPORT GROUPS 88 VOLUNTEERS 91 MUSEUM STAFF 94 BOARD OF TRUSTEES TRUSTEES EMERITI TRUSTEES EX OFFICIO OFFICERS Peter A. Benoliel Hon. Tom Corbett Constance H. Williams Jack R Bershad Governor, Commonwealth Chair, Board of Trustees Dr. Luther W. Brady, Jr. of Pennsylvania and Chair of the Executive Committee Helen McCloskey Carabasi Hon. Michael A. Nutter Mayor, City of Philadelphia H. F. (Gerry) Lenfest Hon. William T. Raymond G. Perelman Coleman, Jr. Hon. Darrell L. Clarke Chairs Emeriti Ruth M. Colket President, City Council Edith Robb Dixon Dennis Alter Hannah L. Henderson Timothy Rub Barbara B. Aronson Julian A. Brodsky B. Herbert Lee The George D. Widener Director and Chief David Haas H. F. (Gerry) Lenfest Executive Officer Lynne Honickman Charles E. Mather III TRUSTEES Victoria McNeil Le Vine Donald W. McPhail Gail Harrity Vice Chairs Marta Adelson Joan M. Johnson David William Seltzer Harvey S. Shipley Miller President and Chief Operating Officer Timothy Rub John R. Alchin Kenneth S. Kaiserman* Martha McGeary Snider Theodore T. Newbold The George D. Widener Dennis Alter James Nelson Kise* Marion Stroud Swingle Lisa S. Roberts Charles J. Ingersoll Director and Chief Barbara B. Aronson Berton E. Korman Joan F. Thalheimer Joan S. -

Michelangelo Pistoletto

GALLERIA CONTINUA Via del Castello 11, San Gimignano (SI), Italia tel. +390577943134 fax +390577940484 [email protected] www.galleriacontinua.com MICHELANGELO PISTOLETTO Opening: Saturday 21 September 2013, Via del Castello 11, 6pm-12 midnight Until 7 January 2014, Monday–Saturday, 10am-1pm 2-7pm Shortly after the end of the successful large-scale exhibition at the Louvre in Paris, Michelangelo Pistoletto is once again showing in Italy with a new project for the Galleria Continua: recent works, a site-specific installation conceived for the stalls area and a substantial number of new pieces realized specially for this exhibition, which draw on Cento mostre nel mese di ottobre (One Hundred Exhibitions in the Month of May). In what is a kind of recipe book of exhibitions and works, published by the Galleria Giorgio Persano in 1976 and containing 100 ideas for a similar number of shows, all conceived and described in the October of that year, the artist wrote: “These exhibitions are planned in the same way as the Oggetti in meno (Minus Objects) of 1966, where every single element is the immediate result of a contingent need. The eventual full-scale execution, though it may seem to be at odds with the logic of the contingency, obeys the logic of the planning, which in my process occupies but one place in a hundred. Indeed, the last exhibition is reserved for the stimulus produced by actual presence on the spot. This truth is capable of absorbing, one by one, all the other 99 truths, except for that of the planning.” The exhibition opens with a series of works from the Vortice (Vortex) cycle: organic or geometric forms cut into black and white mirrors and presented in gilt frames. -

Lévy Gorvy to Present Major Exhibition Devoted to Michelangelo Pistoletto in Collaboration with Galleria Continua

LÉVY GORVY TO PRESENT MAJOR EXHIBITION DEVOTED TO MICHELANGELO PISTOLETTO IN COLLABORATION WITH GALLERIA CONTINUA Michelangelo Pistoletto October 14, 2020–January 9, 2021 Lévy Gorvy 909 Madison Avenue New York The picture has exited the frame, the statue has descended from the plinth. Since then, my work—that is, the aesthetic act—has begun to melt into the spaces of life itself. —Michelangelo Pistolettoi New York—Lévy Gorvy is pleased to announce a major exhibition of works by the renowned Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto. The first US presentation in a decade to feature multiple installations by Pistoletto, it will take visitors on a journey through one of the most influential and enduring artistic practices to unfold from the postwar period to the present. Lévy Gorvy’s exhibition will resonate with the themes that have animated Pistoletto’s body of work for over six decades: perception, time, history, tradition, and the relationship between art, artist, and viewer. Designed by the artist specifically for the gallery’s New York space, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s exhibition is organized in collaboration with Galleria Continua. Upon arriving at Lévy Gorvy, visitors to the exhibition will be greeted by an installation inspired by a pairing included in One and One Makes Three, Pistoletto’s 2017 retrospective at the Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore during the Venice Biennale. Featuring the artist’s signature use of mirrors, the grouping at Lévy Gorvy includes Pistoletto’s historic Viceversa (1971) and the recent Color and Light (2016–17). Together these works create a dynamic, constantly metamorphosing environment and dramatizing the contrast between the fixity of the past and the ever- changing nature of the present. -

Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton//Joseph A. Amato//Amy Balkin//Karen Barad//Pennina Barnett//Artur Barrio// Robert Barry//Roland Barthe

Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton//Joseph A. Amato//Amy Balkin//Karen Barad//Pennina Barnett//Artur Barrio// Robert Barry//Roland Barthes//Georges Bataille// Pascal Beausse//Nicolas Bourriaud//Christine Buci- Glucksmann//Judith Butler//Dan Cameron//Germano Celant//John Chandler//Mel Chin//Tony Conrad// Hubert Damisch//Gilles Deleuze//Jacques Derrida// herman de vries//Georges Didi-Huberman//Jimmie Durham//Natasha Eaton//VALIE EXPORT//Briony Fer// Vilém Flusser//Kenneth Goldsmith//Antony Gormley// Dan Graham//Betsy Greer//Elizabeth Grosz//Nicolás Guagnini//Félix Guattari//Helen Mayer Harrison// Newton Harrison//Jens Hauser//Romuald Hazoumè// Susan Hiller//Dieter Hoffmann-Axthelm//Ian Hunt//Tim Ingold//Ilya Kabakov//Mike Kelley//Wolfgang Kemp// Max Kozloff//Julia Kristeva//Esther Leslie//Primo Levi// Lucy R. Lippard//Jean-François Lyotard//Anthony McCall//Marshall McLuhan//Kristine Marx//Robert Morris//ORLAN//Sadie Plant//Dominic Rahtz//Dietmar Rübel//Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenhoff//Tino Sehgal// Shozo Shimamoto//Robert Smithson//Simon Starling// Simon Taylor//Ann Temkin//Paul Thek//Mierle Laderman Ukeles//Paul Vanouse//Hilke Wagner// Monika Wagner//Kara Walker//Gillian Whiteley// Richard J. Williams//Robert Williams//Jiro Yoshihara Materiality Whitechapel Gallery London The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts M A T E R I A L I T Y Edited by Petra Lange-Berndt Documents of Contemporary Art Co-published by Whitechapel Gallery Series Editor: Iwona Blazwick and The MIT Press Commissioning Editor: Ian Farr Documents of Contemporary Art Project Editor: Francesca Vinter First published 2015 Design by SMITH © 2015 Whitechapel Gallery Ventures Limited Allon Kaye, Justine Schuster All texts © the authors or the estates of the authors, Printed and bound in China unless otherwise stated Cover, front, Robert Smithson, Asphalt Rundown Whitechapel Gallery is the imprint of Whitechapel (1969), October 1969, Rome. -

Michelangelo Pistoletto's Community of Limits Gianmarco Visconti

85 Michelangelo Pistoletto's Community of Limits Gianmarco Visconti This essay takes a look at the career of Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto during the 1960s, seeking to make connections between his work, Italy's shifting social atmosphere and the impetus of youth counterculture at the time. Through the formal analysis of Pistoletto's paintings, sculptures, and performances, the paper culminates in a discussion of the meaning of community and its value in an industrialized world. The 1960s in Italy were coloured by a general discontentment with the institutional “framing” of the art world, in which painting was held above all other mediums. In the United States this discourse was carried out through the development of avant-garde movements such as Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art where, rather than just changing the way art objects were made, many artists opted to change the context in which their works were seen or experienced.1 They brought their abstractions to the street, anywhere outside of the institutional realm of art, and they searched for ways to make art objects vulnerable or even secondary to the space in which they were found.2 Since the 1920s the avant-garde had been mixing its artistic radicalism with politics. In particular, the Surrealists were fond of using Marxist rhetoric to fortify their own goals of freeing the mind from the effects of preexisting societal structures, which hindered its expression. This need for “communal free expression” found itself echoed in the 1960s by various artistic communities -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia Presents

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia presents The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History in collaboration with Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern La Biennale di Venezia President Roberto Cicutto Board Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como Director General Andrea Del Mercato THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

For Immediate Release Metal

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE METAL 17 JANUARY – 23 FEBRUARY 2019 SIMON LEE GALLERY, LONDON CARL ANDRE | GIOVANNI ANSELMO | LUCIANO FABRO | BRUCE NAUMAN | MICHELANGELO PISTOLETTO | RICHARD SERRA Simon Lee Gallery, London is pleased to present Metal, a group exhibition of sculptures in metal produced between 1968 and 1990. The exhibition comprises works created by some of the most prominent and innovative artists of the twentieth century, pioneers of the Minimalist and Arte Povera movements. The exhibition links together artists working in industrial materials such as aluminium, iron, and steel, who challenge the viewer’s relationship to space through various methods of intervention, proposing unexpected ways of seeing and interacting. Richard Serra’s T with Two (1986), barricades one corner of the exhibition space by the most minimal means possible – two rolled plates of steel stacked to resemble a capital T from one perspective; from above, or inside the corner, however, the T-shape forms a new triangular enclosure. Elsewhere, Bruce Nauman’s Triangle (1977-1980) constructs from cast iron a three-point boundary on the floor that at once locks out and barricades in the viewer to the area it sculpts from the gallery space. Nauman explains, ‘I find triangles really uncomfortable, disconcerting kinds of spaces…there is no comfortable space to stay inside them or outside them’. In Michelangelo Pistoletto’s seminal early work, Rittratto sigg. Lerre (1987) polished stainless steel becomes a mirror populated by figures painted to human-scale. The viewer sees themselves in relation to the reflection and the scale of the mirrored surface, allowing them to enter the work conceptually and literally.