2011 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KBR 2020 Proxy Statement

TO OUR FOR MAKING ANYTHING POSSIBLE NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS AND PROXY STATEMENT Dear KBR, Inc. Stockholders, As I write this letter to you for our Proxy Statement, the world is in the middle of a global health crisis. The COVID-19 outbreak is an unprecedented event, and although this is a time of significant uncertainty, we are taking actions to support our people, their families and our customers. With operations in China and South Korea we had an early warning of the potential impact of the virus, and this allowed us to plan ahead and stress test our operations for remote working. I am humbled by the amazing efforts of our people around the globe who have pulled together, shared ideas and implemented best practices to continue to provide world-class service for our customers while also protecting their well-being and the health and safety of their colleagues. It is this can-do, people-centric and forward-thinking culture that makes KBR a great company to be part of. It is thus a great honor to share with you this special Proxy Statement, which marks the 100-year anniversary of our company, and to dedicate it to the people who made it possible — our incredible employees. It is remarkable to think of all they have accomplished throughout KBR’s history, beginning in the earliest days, when they worked with teams of wagons and mules to pave rural roads, to today, when they are helping NASA return to the moon and discover life beyond Earth. Over the past 100 years, KBR has grown into an innovative and dynamic global company, and I am proud to be a part of this journey. -

Massive Spikes

Repair and Rebuild BALANCING NEW MILITARY SPENDING FOR A THREE-THEATER STRATEGY Mackenzie Eaglen OCTOBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Notes ....................................................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 A Brief History of a Failed Barbell Investment Strategy .......................................................................................5 Repair and Rebuild ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 A Note on Methodology ...............................................................................................................................................21 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

1. the Composition, Membership, Vacancies On, And/Or Appointments to Be Made to the Intelligence Oversight Board ('IOB') 2

OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE WASHINGTON, DC 20511 Mr. Mark Rumold Electronic Frontier Foundation 454 Shotwell Street San Francisco, CA 94110 OCT 6 m Reference: DF-2011-00046 Dear Mr. Rumold: This responds to your 15 February 2011 facsimile to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, wherein you requested, under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the following information: 1. The composition, membership, vacancies on, and/or appointments to be made to the Intelligence Oversight Board ('IOB') 2. Any discussions or communications between officials or employees of ODNI and any White House officials or employees regarding the composition, membership, vacancies on, and/or appointments to be made to the IOB. 3. Any discussions or communications between officials or employees of ODNI and officials or employees of other intelligence agencies regarding the composition, membership, vacancies on, and/or appointments to be made to the IOB. 4. Any discussions or communications between officials or employees of ODNI and any member of Congress or congressional staffer regarding the composition, membership, vacancies on, and/or appointments to be made to the IOB. 5. Any discussions or communications regarding the reasons, explanations, or rationales provided for President Obama's appointment of, or the failure to appoint, members to the IOB. As this response completes our processing of your request, we have administratively closed your 28 February 2011 appeal of our denial of expedited processing. Your request was processed in accordance with the FOIA, 5 U.S.C. § 552, as amended. ODNI searches resulted in the location of three documents responsive to your request. -

Nspc UAG NOTES FOURTH PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA October 21, 2019

NSpC UAG NOTES FOURTH PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA October 21, 2019 Courtyard by Marriott, Washington Downtown / Convention Center Shaw Ballroom 901 L Street NW Washington, DC 20001 1:00-1:15 CALL TO ORDER, OPENING REMARKS, & MEETING GOALS James Joseph “JJ” Miller – UAG Executive Secretary Admiral James Ellis, Jr., USN, Retired – UAG Chair 1:15-2:15 EXPERIENCES AND ISSUES OF THE NATIONAL POSITIONING, NAVIGATION, AND TIMING ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Bradford Parkinson – 1st Vice Chair, PNT Advisory Board 2:15-2:45 EXPLORATION & DISCOVERY SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT General Lester Lyles, USAF, Retired – Subcommittee Chair 2:45-3:30 OUTREACH & EDUCATION SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT Colonel Eileen Collins, USAF, Retired – Subcommittee Chair 3:30-3:45 BREAK 3:45-4:15 SPACE POLICY & INTERNATIONAL ENGAGEMENT SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT Dr. David Wolf – Subcommittee Chair 4:15-4:30 NATIONAL SECURITY SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT Admiral James Ellis, Jr., USN, Retired – Subcommittee Chair 4:30-4:45 TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT Colonel Pamela Melroy, USAF, Retired – Subcommittee Chair 4:45-5:15 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & INDUSTRIAL BASE SUBCOMMITTEE REPORT Dr. Mary Lynne Dittmar and Eric Stallmer – Subcommittee Co-Chairs 5:15-5:30 PUBLIC COMMENT 5:30 ADJOURN ORGANIZATIONAL CHART National Space Council Executive Secretary Chair of Users’ Advisory Group Economic Exploration & Development & Discovery IndustrIal Base National Six Outreach & Security Subcommittees Education Space Policy & Technology & International Innovation Engagement USERS’ ADVISORY GROUP SUBCOMMITTEES ECONOMIC EXPLORATION AND NATIONAL SECURITY DEVELOPMENT AND DISCOVERY INDUSTRIAL BASE Adm. James Ellis, Jr. Gen. Lester Lyles (USN, Ret.), Chair Dr. Mary Lynne Dittmar, (USAF, Ret.), Chair Co-Chair Tory Bruno Eric Stallmer, Co-Chair Col. Buzz Aldrin (USAF, Ret.) Dean Cheng Tory Bruno Tim Ellis Tory Bruno Dr. -

2017-Odfprogram LOW-RES-4.Pdf

1 2 Welcome Thank you for attending the second Ohio Defense Forum. This two-day event will serve as an opportunity for discussion with national defense experts about Ohio’s role in maintaining national defense. Last year, the Ohio Defense Forum was created to discuss the future of defense. As home to ten military installations, Ohio is “The Ohio Defense Forum was a bedrock of defense for our country. Since then, the threats created to discuss the future of defense. As home to ten military our country faces have grown dramatically. Nations like North installations, Ohio is a bedrock of Korea, Iran, and Russia pose even greater dangers now than defense for our country.” they did a year ago. I look forward to government, military, and defense industry officials coming together again during these two days to discuss how we can work together more efficiently to keep America safe. Thank you to the Dayton Development Coalition for hosting this event again this year, and thank you to all panelists and participants for their contribution to the ongoing conversation about Ohio’s commitment to defense. Sincerely, Congressman Michael R. Turner 3 4 Venue Map The Ohio State University Ohio Union Ohio Defense Forum Location 5 Tuesday, October 17, 2017 Tuesday, October 17, 2017 9:30 AM Registration Desk Open - Venue Sponsor: The Ohio State University College of Engineering Performance Hall 11:00 AM Buffet Lunch (Provided) - Sponsor: Radiance Technologies Performance Hall 12:00 PM Welcome / Opening Ceremonies Performance Hall - Rachel Castle, Director, Defense Programs, Dayton Development Coalition - National Anthem - Jeff Hoagland, President & CEO, Dayton Development Coalition - Congressman Michael Turner, Ohio Defense Forum Special Guest - Dr. -

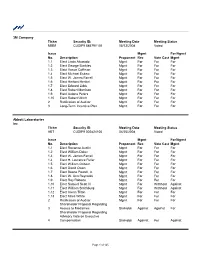

3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 Issue No

3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/13/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 3 Long-Term Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/25/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect William Osborn Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Samuel Scott III Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.11 Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.12 Elect Glenn Tilton Mgmt For For For 1.13 Elect Miles White Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding 3 Access to Medicines ShrHoldr Against Against For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Advisory Vote on Executive 4 Compensation ShrHoldr Against For Against Page 1 of 125 Accenture Limited Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ACN CUSIP9 G1150G111 02/07/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. -

General Dynamics Corporation

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) ☑ Filed by the Registrant ☐ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant CHECK THE APPROPRIATE BOX: ☐ Preliminary Proxy Statement ☐ Confidential, For Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ☑ Definitive Proxy Statement ☐ Definitive Additional Materials ☐ Soliciting Material Under Rule 14a-12 General Dynamics Corporation (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if Other Than the Registrant) PAYMENT OF FILING FEE (CHECK THE APPROPRIATE BOX): ☑ No fee required. ☐ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. 1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: 2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: 3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): 4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: 5) Total fee paid: ☐ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials: ☐ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the form or schedule and the date of its filing. 1) Amount previously paid: 2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: 3) Filing Party: 4) Date Filed: Table of Contents › 2020 Notice of Annual Meeting of Shareholders and Proxy Statement › Table of Contents Letter to Our Shareholders March 26, 2020 DEAR FELLOW SHAREHOLDER: We are pleased to send you the 2020 General Dynamics Proxy Statement. -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. HRG. 108–241, PT. 5 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 1050 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES MARCH 14, 31; APRIL 9, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate 11-SEP-98 16:35 Feb 18, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87327.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004—Part 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES VerDate 11-SEP-98 16:35 Feb 18, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87327.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 S. HRG. 108–241, PT. 5 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 1050 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES MARCH 14, 31; APRIL 9, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services U.S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JULY 25, 2005 No. 102 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was ‘‘The rate increases are forcing some ‘‘It would be so nice if I could stay here, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- doctors in Madison County to take but the way it is, it’s impossible.’’ Dr. pore (Mr. CONAWAY). their practices elsewhere. That is the Sammis has been treating patients at his case for Dr. Charles Sammis, who took family practice in Godfrey for 20 years. Fri- f day was his last day. over his father’s practice 20 years ago. Dr. Sammis says the rising medical mal- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO ‘‘It would be so nice if I could stay TEMPORE practice insurance rates in Madison County here, but the way it is it is impos- have forced him out. He’s not alone, ‘‘The The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- sible.’’ Dr. Sammis has been treating whole Madison County area I think there’s fore the House the following commu- patients at his family practice in God- maybe two to three left and everybody else nication from the Speaker: frey for 20 years. Friday was his last has pretty much either retired or left.’’ Dr. Sammis says frivolous lawsuits are to WASHINGTON, DC, day. Dr. Sammis says the rising medical blame. Not so, says former Missouri Insur- July 25, 2005. -

Membership Biographies

MEMBER BIOGRAPHIES Admiral James Ellis, Jr., USN, Retired User Advisory Group Chairman James O. Ellis, Jr. retired as President and Chief Executive Officer of the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO), located in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 18, 2012. INPO, sponsored by the commercial nuclear industry, is an independent, nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote the highest levels of safety and reliability -- to promote excellence -- in the operation of nuclear electric generating plants. In 2004, Admiral Ellis completed a distinguished 39-year Navy career. His final assignment was Commander of the United States Strategic Command during a time of challenge and change. In this role, he was responsible for the global command and control of United States strategic and space forces, reporting directly to the Secretary of Defense. A 1969 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Admiral Ellis was designated a Naval aviator in 1971. His service as a Navy fighter pilot included tours with two carrier-based fighter squadrons, and assignment as Commanding Officer of an F/A-18 strike/fighter squadron. In 1991, he assumed command of the USS Abraham Lincoln, a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. After selection to Rear Admiral, in 1996 he served as a carrier battle group commander leading contingency response operations in the Taiwan Straits. His shore assignments included numerous senior military staff tours; senior command positions included Commander in Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe and Commander in Chief, Allied Forces, Southern Europe during a time of historic NATO expansion. He led United States and NATO forces in combat and humanitarian operations during the 1999 Kosovo crisis. -

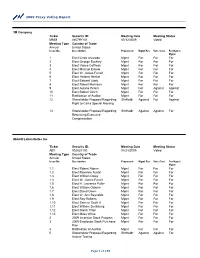

2009 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2009 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM 88579Y101 05/12/2009 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For Against Against 10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 11 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 12 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHoldr Against For Against Right to Call a Special Meeting 13 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHoldr Against Against For Restricting Executive Compensation Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT 002824100 04/24/2009 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1.1 Elect Robert Alpern Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect William Osborn Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Samuel Scott III Mgmt For For For 1.11 Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For For For -

REPORT Defense Contractors' Capture of Pentagon Officials Through the Revolving Door

REPORT BRASS PARACHUTES: Defense Contractors’ Capture of Pentagon Officials Through the Revolving Door November 5, 2018 About THE PROJECT ON GOVERNMENT OVERSIGHT (POGO) IS A NONPARTISAN INDEPENDENT WATCHDOG that investigates and exposes waste, corruption, abuse of power, and when the government fails to serve the public or silences those who report wrongdoing. WE CHAMPION REFORMS to achieve a more effective, ethical, and accountable federal government that safeguards constitutional principles. 1100 G Street, NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20005 WWW.POGO.ORG Acknowledgements The Project On Government Oversight would like to thank all those who have helped compile information used in this report: SCOTT AMEY CHRISTINE OSTROSKY THE CENTER FOR RESPONSIVE POLITICS NICK PACIFICO TOM CHRISTIE VANESSA PERRY LYDIA DENNETT PIERRE SPREY DANNI DOWNING CARTER SALIS LESLIE GARVEY NICK SCHWELLENBACH NEIL GORDON MIA STEINLE DAN GRAZIER EMMA STODDER WILLIAM HARTUNG AMELIA STRAUSS ELIZABETH HEMPOWICZ MARK THOMPSON DAVID JANOVSKY MARC VARTABEDIAN MEG LENTZ WINSLOW WHEELER SEAN MOULTON Thanks to the generous support from: THE CHARLES KOCH FOUNDATION PHILIP A. STRAUS, JR. Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Major Findings .......................................................................................................................................