La Vocalità De La Bohème

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Bohème Program Notes (Michigan Opera Theatre) Christy Thomas Adams, Ph.D

La bohème Program Notes (Michigan Opera Theatre) Christy Thomas Adams, Ph.D. University of Alabama School of Music Since its premiere at the Teatro Regio in Turin in 1896 under the baton of the young Arturo Toscanini, Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème has become one of the world’s most frequently performed operas. It is the first of Puccini’s most celebrated works, which also include Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904), and Turandot (1924), and along with these helped secure his position as the leading Italian opera composer of the era and as Giuseppe Verdi’s presumed successor. In staging canonic operas like La bohème, a major challenge facing opera directors today is how to make these operas fresh, engaging, and relevant. One approach is that of Regietheater or director’s theater, in which an opera’s setting is updated by adding, removing, or altering non-musical elements—for example, situating La bohème in 21st-century rather than 19th-century Paris and transforming Rodolfo and Mimì from a painter and seamstress to graffiti and tattoo artists. Reactions to such approaches are typically mixed: some laud them as visionary ways to reframe familiar works for contemporary audiences, while others criticize them as “Eurotrash,” mere window dressings that privilege a director’s vision over the composer’s. However, in his new production for the Michigan Opera Theatre, Yuval Sharon has taken a different approach, one that will force us to hear and experience this canonic opera anew while lovingly retaining the traditional setting of Puccini’s beloved work. Rather than changing the setting, this new production changes how we progress through what is otherwise a traditional staging: La bohème’s familiar narrative is presented in reverse order, beginning with Act IV and moving through Acts III and II before concluding with Act I. -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

Zur Rolle Von Giacomo Puccinis La Bohème in Norman Jewisons MOONSTRUCK Niclas Stockel (Mainz)

Puccini und Romantic Comedy: Zur Rolle von Giacomo Puccinis La Bohème in Norman Jewisons MOONSTRUCK Niclas Stockel (Mainz) Abstract Unter den zahlreichen Filmproduktionen, die sich Inhalte und Musiken aus Opern zu eigen machen, nimmt der Film MOONSTRUCK (USA 1987, Norman Jewison) eine Sonderposition ein. Ohnehin fragliche Etiketten wie ›Opernfilm‹ und ›Filmoper‹ lassen sich hier nicht anwenden, denn MOONSTRUCK entzieht sich derlei Kategorisierungen: Giacomo Puccinis Oper La Bohème (1896) wird zwar explizit erwähnt, einzelne Aufführungsszenen werden ins Bild gesetzt und das Musikerlebnis einzelner Arien exponiert, doch entspinnt sich all das stets als ein Spiel mit verschiedenen Situationen und Sinnzusammenhängen der Opernhandlung. Interpretations- und Reflexionsräume werden durch den Film gerade da geöffnet, wo sich Analogien nicht so einfach ziehen lassen. Motive aus der Oper, seien sie personeller, emotionaler oder situativer Art, werden aus ihrem Kontext herausgelöst und in den neuen filmischen überführt, wodurch sich Bedeutungsverschiebungen ergeben – eine Verfahrensweise, die der Motivtechnik in der Opernmusik Puccinis ähnlich ist. La Bohème und MOONSTRUCK Etwa neunzig Jahre liegen zwischen den Uraufführungen beider Werke. In dieser Zeitspanne hat sich Puccinis Oper La Bohème zu einer der weltweit meistgespielten Opern entwickelt. Der Film MOONSTRUCK aus dem Jahr 1987 gesellt sich in gewisser Weise zu einer Reihe von zahlreichen Filmproduktionen, die seit Anbeginn der Filmgeschichte den Stoff aus La Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 11, 2014 // 184 Bohème entweder schlicht adaptierten, deren Musik vereinzelt integrierten oder auf sonstige Art zu ihr Bezug nahmen. Hinsichtlich dieser Zuordnung kommt Norman Jewisons Film eine Sonderrolle zu. Der Film verweist gleich auf mehreren Ebenen auf die Oper, ohne jedoch allzu vordergründig deren Handlung zu adaptieren oder einen Großteil der Opernmusik als Filmmusik zu verwenden. -

Simon K. Lee, Tenor

SIMON K. LEE, TENOR Tenor Simon K. Lee was born in Busan, South Korea where he began his musical training. He moved to Italy, where it was discovered that he had a natural affinity for the verismo style. Carlos Montané and Mtro Ubaldo Gardini gave him confidence that his voice suits for Verdi and Puccini. Mr. Lee went on to perform a recital at the first annual Festival Notte Musicali Modenesi in Italy. Mr. Lee then moved to the United States where he participated in the Sherrill Milnes Opera Program and while there worked with Sherrill Milnes and Inci Bashar. Under the direction of world renowned opera singers, Jennifer Larmore and Giacomo Aragall, Mr. Lee continued his career to include his Carnegie Hall debut for Haydn's Paukenmesse with the New England Symphony, Giles Corey in Crucible, Cavaradossi in Tosca, Calaf in Turandot, Rodolfo in La Boheme, Alfredo in La Traviata, Radames in Aida, Duke in Rigoletto, Manrico in Il Trovatore, Riccardo in Un Ballo in Maschera, Rodolfo in La Boheme, 3rd Jew in Salome, Luigi in Il Tabarro, Rinuccio in GianniSchicchi and even a rarely heard Verdi opera the I Lombardi in his Chicago Premiere with the da Corneto Opera as Arvino. Mr. Lee has appeared in the leading tenor roles with companies in the US, Europe as well as in Asia. Mr. Lee has performed with such companies as Singapore Lyric Opera, Busan Natoyan Opera, Opera New Hampshire, Vail Opera, Palm Desert Opera, the Gold & Treasure Coast Operas, Panama City Opera, Utah Festival Opera, da Corneto Opera, Chamber Opera Chicago, Chicago Festival Opera, Kansas City Puccini Festival, Opera North Carolina, Opera Tulsa, Sunstate Opera, Teatro Lirico D'Europa and World Classical Musical Society. -

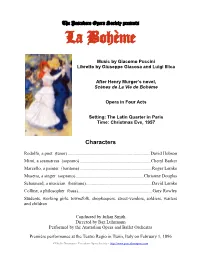

Bob & Phyllis Neumann

The Pescadero Opera Society presents La Bohème Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica After Henry Murger’s novel, Scènes de La Vie de Bohème Opera in Four Acts Setting: The Latin Quarter in Paris Time: Christmas Eve, 1957 Characters Rodolfo, a poet (tenor) ........................................................................ David Hobson Mimì, a seamstress (soprano) .............................................................. Cheryl Barker Marcello, a painter (baritone) ............................................................... Roger Lemke Musetta, a singer (soprano) ............................................................Christine Douglas Schaunard, a musician (baritone) .......................................................... David Lemke Colline, a philosopher (bass) ................................................................. Gary Rowley Students, working girls, townsfolk, shopkeepers, street-vendors, soldiers, waiters and children Conducted by Julian Smith Directed by Baz Luhrmann Performed by the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Première performance at the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy on February 1, 1896 ©Phyllis Neumann • Pescadero Opera Society • http://www.pescaderoopera.com 2 Synopsis Act I A garret in the Latin Quarter of Paris on Christmas Eve, 1957 The near-destitute artist, Marcello and poet Rodolfo try to keep warm on Christmas Eve by feeding the stove with pages from Rodolfo’s latest drama. They are soon joined by their roommates, Colline, a young philosopher, and Schaunard, a musician who has landed a job bringing them all food, fuel and money. While they celebrate their unexpected fortune, the landlord, Benoit, arrives to collect the rent. Plying the older man with wine, the Bohemians urge him to tell of his flirtations, then throw him out in mock indignation at his infidelity to his wife. Schaunard proposes that they celebrate the holiday at the Café Momus. Rodolfo remains behind to try to finish an article, promising to join them later. -

The Taming of Manon and Mimì

i The Taming of Manon and Mimì: Engaging with Women in Puccini’s Operas Emily Siar Senior Honors Thesis Music Department University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fall 2014 Approved: Tim Carter, Thesis Advisor Annegret Fauser, Reader Jeanne Fischer, Reader ii Table of Contents Preface iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Social and Political Climate 3 Gender Onstage 5 An “Effeminate” National Composer? 6 Chapter 2: Manon Lescaut 8 From Novel to Opera 9 Act II: Bad Behavior 13 Chapter 3: La Lupa 18 The Taming of the She-Wolf 20 Chapter 4: La Bohème 24 Mimi’s Transformation 25 “Good Girl” and “Bad Girl” Music 28 Vocal Oppositions 35 The Courtyard Act 36 The Domestication of Musetta 37 Chapter 5: Last Words 40 A Verdian Precedent 40 Non voglio morir! Manon’s Death 42 Silenzio: Mimì’s Death 46 iii Preface I began research on this thesis in the late fall of 2013 under the guidance of Tim Carter. The product that has resulted analyzes the female characters in two operas by Puccini, Manon Lescaut and La Bohème, and one interim project, La Lupa, which was never completed. For this thesis, I have drawn the Italian libretto texts from the website “Libretti d’opera italiani” (http://www.librettidopera.it/), and the English translation of these librettos from Dmitry Murashev’s website (http://www.murashev.com/opera/). The one exception is Musetta’s aria, which was translated by Aaron Green (http://classicalmusic.about.com/od/classicalmusictips/qt/quando-Men-Vo-Lyrics-And-Text- Translation.htm). Although the translations are drawn from Murashev and Green, I have modified some of them to ensure that they are accurate and literal translations of the Italian text. -

Che Gelida Manina from La Boheme by Giacomo Puccini Arranged for String Orchestra by Adrian Mansukhani Sheet Music

Che Gelida Manina From La Boheme By Giacomo Puccini Arranged For String Orchestra By Adrian Mansukhani Sheet Music Download che gelida manina from la boheme by giacomo puccini arranged for string orchestra by adrian mansukhani sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of che gelida manina from la boheme by giacomo puccini arranged for string orchestra by adrian mansukhani sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3554 times and last read at 2021-09-23 14:40:26. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of che gelida manina from la boheme by giacomo puccini arranged for string orchestra by adrian mansukhani you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Cello, Violin Ensemble: String Orchestra Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca By Giacomo Puccini Arranged For String Orchestra By Adrian Mansukhani E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca By Giacomo Puccini Arranged For String Orchestra By Adrian Mansukhani sheet music has been read 12618 times. E lucevan le stelle from tosca by giacomo puccini arranged for string orchestra by adrian mansukhani arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 20:33:55. [ Read More ] Che Gelida Manina From La Boheme For Concert Band Che Gelida Manina From La Boheme For Concert Band sheet music has been read 3246 times. Che gelida manina from la boheme for concert band arrangement is for Advanced level. -

La Bohème Was Made Possible by a Generous Gift from Mrs

laGIACOMO PUCCINI bohème conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Franco Zeffirelli Luigi Illica, based on the novel Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger set designer Franco Zeffirelli Tuesday, November 29, 2016 costume designer 7:30–10:30 PM Peter J. Hall lighting designer Gil Wechsler revival stage director J. Knighten Smit The production of La Bohème was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club general manager Peter Gelb music director emeritus James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi 2016–17 SEASON The 1,300th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S la bohème conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance marcello muset ta Massimo Cavalletti Brigitta Kele rodolfo customhouse serge ant Piotr Beczała Yohan Yi colline customhouse officer Ryan Speedo Green* Joseph Turi schaunard Patrick Carfizzi benoit Paul Plishka mimì Kristine Opolais parpignol Daniel Clark Smith alcindoro Paul Plishka Tuesday, November 29, 2016, 7:30–10:30PM MARTY SOHL/METROPOLITAN OPERA MARTYSOHL/METROPOLITAN A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Puccini’s La Bohème Musical Preparation Howard Watkins, J. David Jackson, Thomas Bagwell, and Joshua Greene Assistant Stage Director Gregory Keller Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Associate Designer David Reppa Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ladies millinery by Reggie G. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990

A GALA OPERATIC EVENING MlRELLA FRENI, soprano and Peter Dvorsky, tenor Members of the J3 Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Fiore Presented by the BOSTON OPERA ASSOCIATION Sunday, February 11, 1990, at 8 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston m ® The Boston Opera Association Mrs. Russell J. Rowell, President Vice-Presidents V.J Hon. Charles Francis Mahoney Anthony D. Ostrom James D. St. Clair David C. Crockett Hon. Lawrence T. Perera Chairman, Board of Overseers Chairman, Board of Directors Robert L. Culver Robert L. Klivans Treasurer Secretary Bruce R. Bengston Michael J. Puzo Assistant Treasurer Assistant Secretary Board of Directors Mrs. Frank G. Allen Dr. Melvin D. Field Dr. Daniel H. Perlman Mr. John T. Bennett, Jr. Mr. Eugene M. Freedman Mr. William S. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bleakie Mr. Martin Gantshar Mr. John Ryan Mrs. Mary Louise Cabot Mr. Gerard A. Glass Mrs. George Lee Sargent Mr. Robert Cahners Mr. Milton L. Glass Mrs. Jacquelyn Scheinbart Mr. William I. Cowin Miss Sally Hurlbut Mr. Robert H. Scott Dean Phyllis Curtin Mrs. Myra Kraft Dr. Lawrence T. Shields Miss Catharine-Mary Donovan Mrs. J. Peter Lyons Mr. Johannes Spanjaard Mr. George Ellison Mr. Donald M. Manzelli Mr. Charles A. Steward Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. Nancy Rice Morss Mrs. Lucius Thayer Board of Overseers Mr. Frank G. Allen, Jr. Mrs. Henry S. Hall, Jr. Mrs. Barbara C. Riley Mr. Robert B.M. Barton Mrs. Henry M. Halvorson Miss Ann Sargent Mrs. Ralph Bradley Mr. Robert Hilliard Mrs. Frederic W. Schwartz Mr. Max Canter Mrs. Robert Douglas Hunter Mrs. Theodore C. Sturtevant Mr. -

Pathways for Understanding; La Boheme

2 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Bohème 5 The History of Puccini’s La Bohème 7 Guided Listening Che gelida manina! 10 Sì. Mi chiamano Mimì 11 O soave fanciulla 12 Quando me'n vo' 13 Donde lieta uscì 14 O Mimì, tu più non torni 15 Vecchia zimarra, senti 16 La Bohème Resources About the Composer 17 Puccini, Verismo, and La Bohème 20 Online Resources 23 Additional Resources The Emergence of Opera 24 Metropolitan Opera Facts 28 Reflections after the Opera 30 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 31 Glossary 32 References Works Consulted 36 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. Main topics and questions are introduced, giving teachers of all musical backgrounds (or none at all) the means to discuss the music of the opera with their students. -

Program Notes

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER March 28, 2001 8:00 PM on PBS New York City Opera Puccini's La Bohème Our next Live From Lincoln Center telecast, on Wednesday evening, March 28, will be devoted to the acclaimed New York City Opera production of Puccini's La Bohème brought to you direct from the stage of the New York State Theater at New York City's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. We take for granted the primacy of Giacomo Puccini as a composer of operas. Yet in common with many composers Puccini was not an instant success. Two operas he composed in the1880s, "Le villi" (1884) and "Edgar" (1889), indicated little by way of mastery of the idiom, but they paved the way for his first genuine success, "Manon Lescaut" of 1893. Indeed, a young London music critic named George Bernard Shaw wrote perspicaciously in 1894: "Puccini looks to me more like the heir of Verdi than any of his rivals." In casting about for his next opera, Puccini and his librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, decided upon a setting of the 1854 novel, "Scènes de la vie de Bohème", by the Frenchman, Henry Murger. Their "La bohème" was three years in the making. After its first performance, conducted by 28-year old Arturo Toscanini in February, 1896, its success can be described as moderate, at best. One local Turin critic even described it as "empty and downright infantile." The press reaction four years later when "La bohème" was performed for the first time by the Metropolitan Opera in New York was not much better: the critic of the New York Tribune described it as "foul in subject and fulminant and futile in its music." He went on to say the work was "silly and inconsequential." But Puccini's publisher, Giulio Ricordi, quickly recognized the value of the opera. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

SouthamptoUr^rVIERSHT-Y C)F n University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright Notice Copyright and Moral Rights for this chapter are retained by the copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This chapter cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. the content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the rights holder. When referring to this work state full bibliographic details including the author of the chapter, title of the chapter, editor of the book , title of the book, publisher, place of publication, year of publication, page numbers of the chapter Author of the chapter William Drabkin Title of the chapter The musical language of La boheme Editor/s Arthur Groos and Roger Parker Title of the book Giacomo Puccini: La boheme ISBN 0521319137 Publisher Cambridge University Press Place of publication Cambridge, UK Year of publication 1986 Chapter/Page numbers 80-101 5 BY WILLIAM DRABKIN Few people would deny that Puccini's reputation as a composer was made, and has been upheld, in the opera house, and that interest in his music has been largely confined to this estabhshment and the journahstic world surrounding it. Fifty years after the appearance of the first substantial study of a Puccini opera worthy of the term 'analysis', his musical scores are all but ignored by serious music journals and university analysis seminars, places from which informed critical opinion on other musical matters has long flowed in abundance.