La Bohème Program Notes (Michigan Opera Theatre) Christy Thomas Adams, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

Idomeneo” on Crete “

“Idomeneo” on Crete by Heather Mac Donald The humanists who created the first operas out to be his son, Idamante, whom, in Cam- in late sixteenth-century Florence hoped to re- pra’s opera, the king does indeed sacrifice be- capture the emotional impact of ancient Greek fore going mad. Such a dark ending no longer tragedy. It would take nearly another 200 years, suited Enlightenment tastes, however, and in however, for the most powerful aspect of Attic Mozart’s libretto, by the Salzburg cleric Giam- drama— the chorus—to reach its full potential battista Varesco, the gods grant Idomeneo a on an opera stage. That moment arrived with last-minute reprieve from his vow and rule is Mozart’s 1781 opera Idomeneo, re di Creta. This amicably passed from father to son. September, Opera San José performed Idome- The delight that Mozart must have had in neo’s sublime choruses with thrilling clarity and composing for the Mannheimers is palpable force, in a striking new production of the op- in Idomeneo’s dynamic score. And it is in the era that wedded a philanthropist’s archeologi- opera’s nine choruses that the orchestral writ- cal passion with his love for Mozart. San José’s ing reaches its pinnacle. In the celebrations Idomeneo was a reminder of the breadth of classi- of the Trojan War’s end—“Godiam la pace” cal music excellence in the United States, as well (“Let us savor peace”) and “Nettuno s’onori” as of the value of philanthropy guided by love. (“Let Neptune be honored”)—the strings In 1780, the twenty-four-year-old Mozart re- skitter jubilantly through complex rhythms ceived his most prestigious commission yet: to and rapid volume changes, while the winds compose an opera for the Court of Bavaria to embroider fleet counterpoint around the open Munich’s Carnival season. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Music on Stage

Music on Stage Music on Stage Edited by Fiona Jane Schopf Music on Stage Edited by Fiona Jane Schopf This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Fiona Jane Schopf and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7603-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7603-2 TO SUE HUNT - THANK YOU FOR YOUR WISE COUNSEL TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................................... x List of Tables .............................................................................................. xi Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Acknowledgments .................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Opera, the Musical and Performance Practice Jane Schopf Part I: Opera Chapter One ................................................................................................. 8 Werktreue and Regieoper Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe -

La Regìa Lirica, Livello Contemporaneo Della Regìa Teatrale

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Il Castello di Elsinore (E-Journal) La regìa lirica, livello contemporaneo saggi della regìa teatrale Gerardo Guccini Dal “repertorio” al “festival permanente” Il radicamento sistemico della regìa lirica è stato storicamente favorito da una tra- sformazione organizzativa e istituzionale affatto indipendente dai percorsi e dalle saggi poetiche dei singoli artisti teatrali. Mi riferisco all’adeguamento delle programma- 83 zioni liriche al modello del festival che ha affidato la responsabilità degli allestimen- ti operistici a registi del teatro di prosa e cinematografici, a coreografi e a maestri dell’innovazione, comportando, così, l’innalzamento del livello visuale, l’affina- mento di quello recitativo, la mobilitazione delle risorse tecnologiche e una gran- de varietà di scelte stilistiche. Mentre il teatro lirico di repertorio, ancora vitale ne- gli anni Cinquanta del secolo passato, prevedeva – numerose rappresentazioni per ciascuna opera, – numerose opere rappresentate, – una stagione concepita secondo il metodo dell’alternanza, – una compagnia stabile di cantanti, – allestimenti poco sofisticati e rinnovati solo di rado, la programmazioni riformulate secondo il modello del festival richiedono – numero limitato di rappresentazioni, – numero limitato di opere, date in lingua originale, – stagione concepita secondo il principio della serie e non più dell’alternanza, 83-104 pp. – star del canto scritturate per una singola parte, • 62 – regìe elaborate e frequentemente rinnovate1. • 1. Le premesse e gli effetti dell’adeguamento delle stagioni liriche al modello del festival sono esa- minati in X. Dupuis, Analyse économique de la production lyrique, Cahier du LES, Université de Paris I Panthéon - Sorbonne, Paris 1979. -

Nyco Renaissance

NYCO RENAISSANCE JANUARY 10, 2014 Table of Contents: 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 2. History .......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Core Values .................................................................................................................................. 5 4. The Operatic Landscape (NY and National) .............................................................................. 8 5. Opportunities .............................................................................................................................. 11 6. Threats ......................................................................................................................................... 13 7. Action Plan – Year 0 (February to August 2014) ......................................................................... 14 8. Action Plan – Year 1 (September 2014 to August 2015) ............................................................... 15 9. Artistic Philosophy ...................................................................................................................... 18 10. Professional Staff, Partners, Facilities and Operations ............................................................. 20 11. Governance and Board of Directors ......................................................................................... -

Zur Rolle Von Giacomo Puccinis La Bohème in Norman Jewisons MOONSTRUCK Niclas Stockel (Mainz)

Puccini und Romantic Comedy: Zur Rolle von Giacomo Puccinis La Bohème in Norman Jewisons MOONSTRUCK Niclas Stockel (Mainz) Abstract Unter den zahlreichen Filmproduktionen, die sich Inhalte und Musiken aus Opern zu eigen machen, nimmt der Film MOONSTRUCK (USA 1987, Norman Jewison) eine Sonderposition ein. Ohnehin fragliche Etiketten wie ›Opernfilm‹ und ›Filmoper‹ lassen sich hier nicht anwenden, denn MOONSTRUCK entzieht sich derlei Kategorisierungen: Giacomo Puccinis Oper La Bohème (1896) wird zwar explizit erwähnt, einzelne Aufführungsszenen werden ins Bild gesetzt und das Musikerlebnis einzelner Arien exponiert, doch entspinnt sich all das stets als ein Spiel mit verschiedenen Situationen und Sinnzusammenhängen der Opernhandlung. Interpretations- und Reflexionsräume werden durch den Film gerade da geöffnet, wo sich Analogien nicht so einfach ziehen lassen. Motive aus der Oper, seien sie personeller, emotionaler oder situativer Art, werden aus ihrem Kontext herausgelöst und in den neuen filmischen überführt, wodurch sich Bedeutungsverschiebungen ergeben – eine Verfahrensweise, die der Motivtechnik in der Opernmusik Puccinis ähnlich ist. La Bohème und MOONSTRUCK Etwa neunzig Jahre liegen zwischen den Uraufführungen beider Werke. In dieser Zeitspanne hat sich Puccinis Oper La Bohème zu einer der weltweit meistgespielten Opern entwickelt. Der Film MOONSTRUCK aus dem Jahr 1987 gesellt sich in gewisser Weise zu einer Reihe von zahlreichen Filmproduktionen, die seit Anbeginn der Filmgeschichte den Stoff aus La Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 11, 2014 // 184 Bohème entweder schlicht adaptierten, deren Musik vereinzelt integrierten oder auf sonstige Art zu ihr Bezug nahmen. Hinsichtlich dieser Zuordnung kommt Norman Jewisons Film eine Sonderrolle zu. Der Film verweist gleich auf mehreren Ebenen auf die Oper, ohne jedoch allzu vordergründig deren Handlung zu adaptieren oder einen Großteil der Opernmusik als Filmmusik zu verwenden. -

Audiovisual Recording As Registers of Opera Productions1

Comunicação e Sociedade, vol. 31, 2017, pp. 39 – 56 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.31(2017).2603 The world in a bottle and the archeology of staging: audiovisual recording as registers of opera productions1 Mateus Yuri Passos Abstract This work focuses on the use of the audiovisual opera recording as a document to analyze contemporary stagings labeled by the German critics as director’s theater [Regietheater]. In direc- tor’s theater, Wagner’s total artwork project [Gesamtkunstwerk] achieves a turn in meaning, for the three artistic dimensions of opera – word, music and staging – become different texts. In this paper, we discuss the limitations of audiovisual recording as a register of director’s theater opera stagings, as well as filmic resources that allow for a reconstruction of the audiovisual text of such productions with solutions that are often quite distinct from those adopted on the stage. We are in- terested above all in problematizing the equivalence that is sometimes established between a stag- ing and its recording – especially in the contemporary context of productions that frequently suffer considerable changes and are characterized by the unique aspect of each performance, always full of singular events and relatively autonomous regarding the general plan of the director. Thus, we will discuss problems and solutions of video direction of audiovisual recordings of stagings of the operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen [The Ring of Nibelungo], by Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Keywords Opera recording; director’s theater; opera staging; Regietheater; Richard Wagner Resumo Este trabalho se debruça sobre o uso de gravações audiovisuais como documentos para análise de producções de ópera contemporâneas agrupadas pela crítica alemã sob o termo tea- tro de director [Regietheater]. -

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe ALLEA ALLEuropean A cademies Published on behalf of ALLEA Series Editor: Günter Stock, President of ALLEA Volume 2 The Role of Music in European Integration Conciliating Eurocentrism and Multiculturalism Edited by Albrecht Riethmüller ISBN 978-3-11-047752-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047959-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047755-9 ISSN 2364-1398 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover: www.tagul.com Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Foreword by the Series Editor There is a debate on the future of Europe that is currently in progress, and with it comes a perceived scepticism and lack of commitment towards the idea of European integration that increasingly manifests itself in politics, the media, culture and society. The question, however, remains as to what extent this report- ed scepticism truly reflects people’s opinions and feelings about Europe. We all consider it normal to cross borders within Europe, often while using the same money, as well as to take part in exchange programmes, invest in enterprises across Europe and appeal to European institutions if national regulations, for example, do not meet our expectations. -

Simon K. Lee, Tenor

SIMON K. LEE, TENOR Tenor Simon K. Lee was born in Busan, South Korea where he began his musical training. He moved to Italy, where it was discovered that he had a natural affinity for the verismo style. Carlos Montané and Mtro Ubaldo Gardini gave him confidence that his voice suits for Verdi and Puccini. Mr. Lee went on to perform a recital at the first annual Festival Notte Musicali Modenesi in Italy. Mr. Lee then moved to the United States where he participated in the Sherrill Milnes Opera Program and while there worked with Sherrill Milnes and Inci Bashar. Under the direction of world renowned opera singers, Jennifer Larmore and Giacomo Aragall, Mr. Lee continued his career to include his Carnegie Hall debut for Haydn's Paukenmesse with the New England Symphony, Giles Corey in Crucible, Cavaradossi in Tosca, Calaf in Turandot, Rodolfo in La Boheme, Alfredo in La Traviata, Radames in Aida, Duke in Rigoletto, Manrico in Il Trovatore, Riccardo in Un Ballo in Maschera, Rodolfo in La Boheme, 3rd Jew in Salome, Luigi in Il Tabarro, Rinuccio in GianniSchicchi and even a rarely heard Verdi opera the I Lombardi in his Chicago Premiere with the da Corneto Opera as Arvino. Mr. Lee has appeared in the leading tenor roles with companies in the US, Europe as well as in Asia. Mr. Lee has performed with such companies as Singapore Lyric Opera, Busan Natoyan Opera, Opera New Hampshire, Vail Opera, Palm Desert Opera, the Gold & Treasure Coast Operas, Panama City Opera, Utah Festival Opera, da Corneto Opera, Chamber Opera Chicago, Chicago Festival Opera, Kansas City Puccini Festival, Opera North Carolina, Opera Tulsa, Sunstate Opera, Teatro Lirico D'Europa and World Classical Musical Society. -

13895 Wagner News

No: 213 April 2014 Wagner news Number 213 April 2014 CONTENTS 4 Reports of Committee meetings Andrea Buchanan 5 Wagner Society 2014 Bayreuth Ballot Winners Andrea Buchanan 6 Announcement of Wagner Society 2014 AGM Andrea Buchanan 8 Monte Carlo Rheingold Katie Barnes 13 Chéreau Ring : A contrary view Robert Mitchell 14 Melbourne Ring Ian Rickword 17 Covent Garden Parsifal Katie Barnes 22 Parsifa l: Beauty is in the eye and the ear of the beholder Hilary Reid Evans 23 Regeneration in Parsifal Charles Ellis 24 Masterclasses with Richard Berkeley-Steele Katie Barnes 28 Bromley Symphony Orchestra Die Walküre Act I (photo-essay) Richard Carter 29 Parsifal : Staging an enigma David Edwards 30 Storms at Sea: Three Anniversary Year Reflections John Crowther 32 Illustrated Recital: Wagner and the Dream King Roger Lee 34 News of Young Artists: Our Young Singers: A Progress Report Andrea Buchanan 36 News of Young Artists: Amanda Echalaz Malcolm Rivers 37 Rehearsal Orchestra / Mastersingers: Scenes from Tristan und Isolde, 19 th Oct 2014 38 Après le déluge : Mastersingers / MCL Weekend in Aldeburgh, 12 th –14 th Sept 2014 40 Book review: Walter Widdop: The Great Yorkshire Tenor Richard Hyland 41 Book review: Richard Wagner: The Lighter Side Roger Lee 42 Venues for Wagner Society Events Peter Leppard 43 Wagner Society Contacts 44 Wagner Society Forthcoming Events Peter Leppard Cover photo by Clive Barda for the Covent Garden production of Parsifal reviewed on pages 17 to 23 Printed by Rap Spiderweb – www.rapspiderweb.com 0161 947 3700 EDITOR’S NOTE How do you solve a problem like Parsifal ? Why is it that many of us would prefer to attend a concert performance of what may be regarded as the most sublime of Wagner’s music than to watch a staged performance of the work described by David Edwards on page 29 as having the ability “to set us at loggerheads from virtually the first bar”? He asks whether it is possible to get even close to realising on stage a work that is so densely layered, nuanced and mystically suggestive in its musical atmosphere. -

Bob & Phyllis Neumann

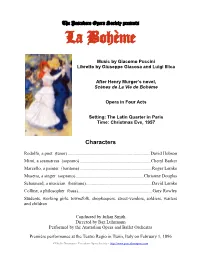

The Pescadero Opera Society presents La Bohème Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica After Henry Murger’s novel, Scènes de La Vie de Bohème Opera in Four Acts Setting: The Latin Quarter in Paris Time: Christmas Eve, 1957 Characters Rodolfo, a poet (tenor) ........................................................................ David Hobson Mimì, a seamstress (soprano) .............................................................. Cheryl Barker Marcello, a painter (baritone) ............................................................... Roger Lemke Musetta, a singer (soprano) ............................................................Christine Douglas Schaunard, a musician (baritone) .......................................................... David Lemke Colline, a philosopher (bass) ................................................................. Gary Rowley Students, working girls, townsfolk, shopkeepers, street-vendors, soldiers, waiters and children Conducted by Julian Smith Directed by Baz Luhrmann Performed by the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Première performance at the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy on February 1, 1896 ©Phyllis Neumann • Pescadero Opera Society • http://www.pescaderoopera.com 2 Synopsis Act I A garret in the Latin Quarter of Paris on Christmas Eve, 1957 The near-destitute artist, Marcello and poet Rodolfo try to keep warm on Christmas Eve by feeding the stove with pages from Rodolfo’s latest drama. They are soon joined by their roommates, Colline, a young philosopher, and Schaunard, a musician who has landed a job bringing them all food, fuel and money. While they celebrate their unexpected fortune, the landlord, Benoit, arrives to collect the rent. Plying the older man with wine, the Bohemians urge him to tell of his flirtations, then throw him out in mock indignation at his infidelity to his wife. Schaunard proposes that they celebrate the holiday at the Café Momus. Rodolfo remains behind to try to finish an article, promising to join them later.