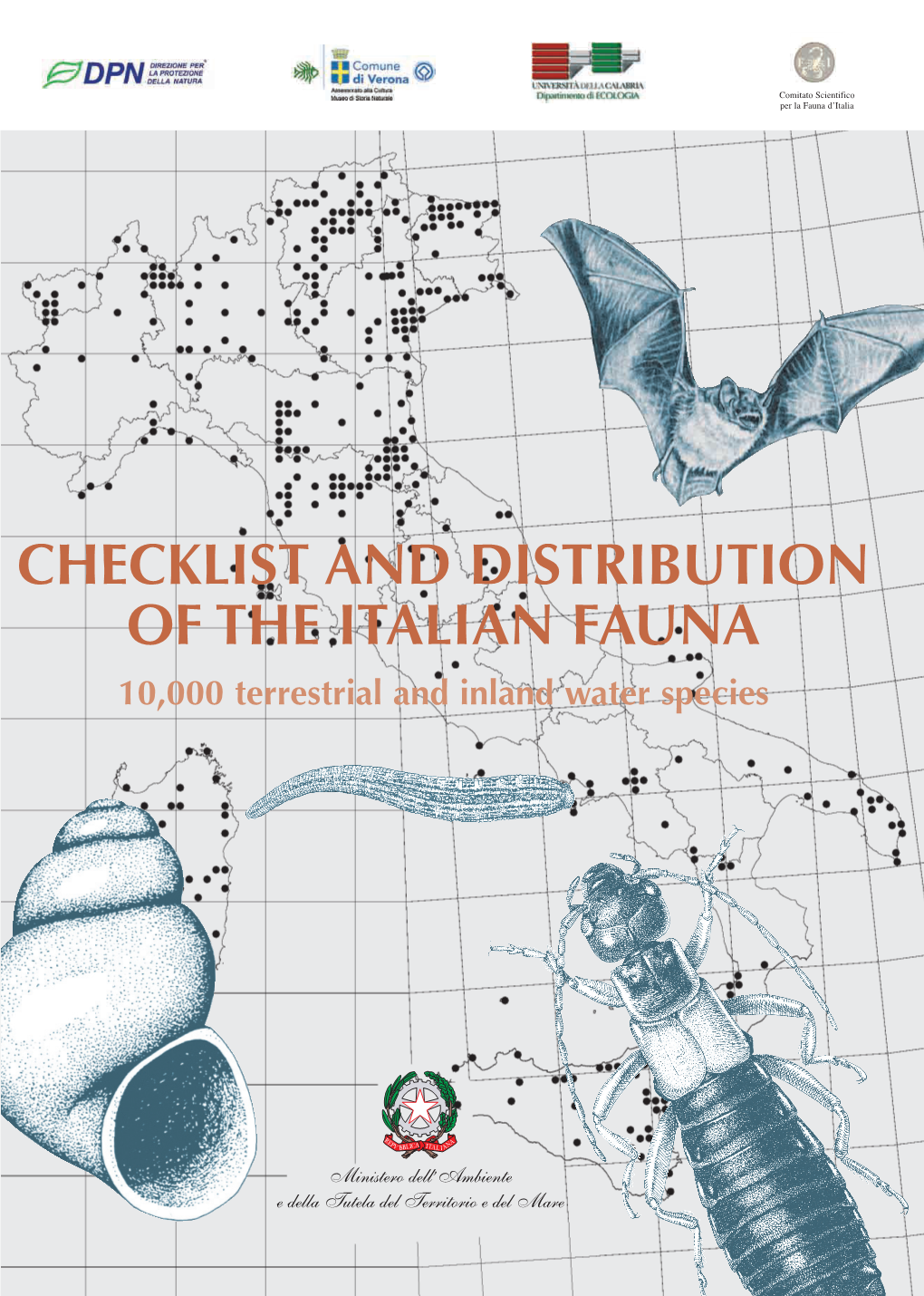

CHECKLIST and DISTRIBUTION of the ITALIAN FAUNA 10,000 Terrestrial and Inland Water Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sphecidae" (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae & Crabronidae) from Sicily (Italy) and Malta

Linzer biol. Beitr. 35/2 747-762 19.12.2003 New records of "Sphecidae" (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae & Crabronidae) from Sicily (Italy) and Malta C. SCHMID-EGGER Abstract: Two large samples from Sicily and Malta are revised. They include 126 species from Sicily, 19 species of them are new for the fauna of Sicily: Astata gallica, Belomicrus italicus, Crabro peltarius bilbaoensis, Crossocerus podagricus, Gorytes procrustes, Lindenius albilabris, Lindenius laevis, Passaloecus pictus, Pemphredon austrica, Pemphredon lugubris, Rhopalum clavipes, Spilomena troglodytes, Stigmus solskyi, Synnevrus decemmaculatus, Tachysphex julliani, Trypoxylon kolazyi, Trypoxylon medium. Miscophus mavromoustakisi, found in Sicily, is also new for the fauna of Italy. A species of the genus Synnevrus is probably unknown to science. The total number of species in Sicily is 217 now. Zoogeographical aspects are discussed. Most of the recorded species are by origin from central or southern Europe. A few species have an eastern, resp. western Mediterranean distribution pattern. A species is a northern African element. Key words: Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Sphecidae, Crabronidae, Sicily, Italy, Malta, fauna, zoogeographical aspects, endemism. Introduction The fauna of Sphecidae from Sicily was never treated in a special publication. PAGLIANO (1990), in his catalogue of the Sphecidae from Italy, was the first who listed all published records of Sphecidae from Sicily. NEGRISOLO (1995) completed the listing in the ‘Checklist della specie della fauna Italiana’. He listed 186 species names, and some subspecies names from Sicily. Nevertheless, the fauna of Sicily is far from being completely known. I had the opportunity to examine two large collections from Sicily. Bernhard Merz collected in June 1999 Diptera at Sicily and Malta and took also many Aculeate with him. -

Dataset Paper New Distributional Data of Butterflies in the Middle of the Mediterranean Basin: an Area Very Sensitive to Expected Climate Change

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Dataset Papers in Science Volume 2014, Article ID 176471, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/176471 Dataset Paper New Distributional Data of Butterflies in the Middle of the Mediterranean Basin: An Area Very Sensitive to Expected Climate Change Stefano Scalercio Consiglio per la Ricerca e la Sperimentazione in Agricoltura, Unita` di Ricerca per la Selvicoltura in Ambiente Mediterraneo, Contrada Li Rocchi-Vermicelli, Rende, 87036 Cosenza, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Stefano Scalercio; [email protected] Received 6 November 2013; Accepted 6 March 2014; Published 12 May 2014 Academic Editors: P. Nowicki, B. Qian, and B. Schatz Copyright © 2014 Stefano Scalercio. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Butterflies are known to be very sensitive to environmental changes. Species distribution is modified by climate warming with latitudinal and altitudinal range shifts, but also environmental perturbations modify abundance and species composition of communities. Changes can be detected and described when large datasets are available, but unfortunately only for few Mediterranean countries they were created. The butterfly fauna of the Mediterranean Basin is very sensitive to climate warming and there is an urgent need of large datasets to investigate and mitigate risks such as local extinctions or new pest outbreaks. The fauna of Calabria, the southernmost region of peninsular Italy, is composed also of European species having here their southern range. The aim of this dataset paper is to increase and update the knowledge of butterfly distribution in a region very sensitive to climate warming that can become an early-warning area. -

Sovraccoperta Fauna Inglese Giusta, Page 1 @ Normalize

Comitato Scientifico per la Fauna d’Italia CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA FAUNA THE ITALIAN AND DISTRIBUTION OF CHECKLIST 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species and inland water 10,000 terrestrial CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species ISBNISBN 88-89230-09-688-89230- 09- 6 Ministero dell’Ambiente 9 778888988889 230091230091 e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare CH © Copyright 2006 - Comune di Verona ISSN 0392-0097 ISBN 88-89230-09-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers and of the Authors. Direttore Responsabile Alessandra Aspes CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species Memorie del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona - 2. Serie Sezione Scienze della Vita 17 - 2006 PROMOTING AGENCIES Italian Ministry for Environment and Territory and Sea, Nature Protection Directorate Civic Museum of Natural History of Verona Scientifi c Committee for the Fauna of Italy Calabria University, Department of Ecology EDITORIAL BOARD Aldo Cosentino Alessandro La Posta Augusto Vigna Taglianti Alessandra Aspes Leonardo Latella SCIENTIFIC BOARD Marco Bologna Pietro Brandmayr Eugenio Dupré Alessandro La Posta Leonardo Latella Alessandro Minelli Sandro Ruffo Fabio Stoch Augusto Vigna Taglianti Marzio Zapparoli EDITORS Sandro Ruffo Fabio Stoch DESIGN Riccardo Ricci LAYOUT Riccardo Ricci Zeno Guarienti EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Elisa Giacometti TRANSLATORS Maria Cristina Bruno (1-72, 239-307) Daniel Whitmore (73-238) VOLUME CITATION: Ruffo S., Stoch F. -

A New Species for the Bee Fauna of Italy: Dasypoda Crassicornis (Friese, 1896) (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae: Dasypodainae) Marco Bonifacino

A new species for the bee fauna of Italy: Dasypoda crassicornis (Friese, 1896) (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae: Dasypodainae) Marco Bonifacino To cite this version: Marco Bonifacino. A new species for the bee fauna of Italy: Dasypoda crassicornis (Friese, 1896) (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae: Dasypodainae). OSMIA, Observatoire des Abeilles, 2021, 9, pp.1-6. 10.47446/OSMIA9.1. hal-03123435 HAL Id: hal-03123435 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03123435 Submitted on 27 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Revue d’Hyménoptérologie Volume 9 Journal of Hymenopterology 2021 ISSN 2727-3806 https://doi.org/10.47446/OSMIA ARTICLE A new species for the bee fauna of Italy: Dasypoda crassicornis (FRIESE, 1896) (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae: Dasypodainae) Marco BONIFACINO1 BONIFACINO, M. (2021). A new species for the bee fauna of Italy: Dasypoda crassicornis (FRIESE, 1896) (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae: Dasypodainae). Osmia, 9: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.47446/OSMIA9.1 Abstract The first records of Dasypoda crassicornis (FRIESE, 1896) for Italy are reported. The species was found in three sites in western Liguria and the Piedmont Cottian Alps, thus extending its eastern range limit, previously known in France. -

A Review of the Villafranchian Fossiliferous Sites of Latium in The

Quaternary Science Reviews 191 (2018) 299e317 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev A review of the Villafranchian fossiliferous sites of Latium in the framework of the geodynamic setting and paleogeographic evolution of the Tyrrhenian Sea margin of central Italy * F. Marra a, , C. Petronio b, L. Salari b, F. Florindo a, c, B. Giaccio c, G. Sottili b a Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Via di Vigna Murata 605, 00143 Roma, Italy b Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Sapienza, Universita di Roma, P.le Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Roma, Italy c Istituto di Geologia Ambientale e Geoingegneria - CNR, Via Salaria km 29.300, 00015 Montelibretti, Roma, Italy article info abstract Article history: In the present study we provide a paleontological and chronostratigraphic review of the Villafranchian Received 18 August 2017 fossiliferous sites of Latium, revising the biochronologic attribution based on their framing within the Received in revised form geodynamic and paleogeographic evolutionary picture for this region. Aimed at this scope, we recon- 24 April 2018 struct the sedimentary and structural history of the Early Pleistocene marine basins through the review Accepted 10 May 2018 and the regional correlation of published stratigraphic sections and borehole data. Moreover, we combine the chronostratigraphic constraints provided in this study to the near-coast deposits of Gelasian-Santernian age (2.58e1.5 Ma) with the results of a recent geomorphologic study of this area, Keywords: Villafranchian allowing us to reconstruct a suite of terraced paleo-surfaces correlated with marine isotopic stages 21 Central Italy through 5. -

Distribution and Status of the Apennine Hare Lepus Corsicanus in Continental Italy and Sicily

Oryx Vol 35 No 3 July 2001 Distribution and status of the Apennine hare Lepus corsicanus in continental Italy and Sicily Francesco M. Angelici and Luca Luiselli Abstract The current distribution of Lepus corsicanus gered on the IUCN Red List. Conservation recommen- (recently considered to be a distinct species from dations for this species are presented. L. europaeus) in peninsular Italy and Sicily is presented in this paper. Our data suggest that L. corsicanus is Keywords conservation, distribution, Italy, Lepus declining markedly in mainland Italy, and perhaps also corsicanus, status. in Sicily, and that it should be categorised as Endan- collected hares during the 1980s and identified an Introduction and historical background additional characteristic of L. corsicanus from northern In 1898 a new hare Lepus corsicanus native to Corsica was Latium (central Italy); this was an anthracite-grey described (De Winton, 1898). Descriptions of its mor- colouration of the nape of the neck. Angelici & Luiselli phometric and morphological characteristics can be (2000) analysed a sample of freshly killed hares found in Palacios et al. (1989), Palacios (1996) and (n = 42) and showed that L. europaeus and L. corsicanus Angelici & Luiselli (2000). De Winton suggested that are clearly different in terms of six biometric charac- this hare was also found in central and southern Italy, teristics. These results seem to confirm Palacios's Sicily and Elba. Of the 'historical' specimens in various (1996) opinion on the specific status of L. corsicanus. collections, the northernmost came from Elba, whereas Amori et al. (1996) proposed the common name of the northernmost in mainland Italy came from the Apennine hare for L. -

The Gelechiidae of the Longarini Salt Marsh in the “Pantani Della Sicilia

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Bella, S.; Karsholt, O. The Gelechiidae of the Longarini salt marsh in the “Pantani della Sicilia Sud-Orientale” nature reserve in southeastern Sicily, Italy (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 43, núm. 171, septiembre, 2015, pp. 365-375 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45543215004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 365-375 The Gelechiidae of the 7/9/15 15:27 Página 365 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 43 (171), septiembre 2015: 365-375 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 The Gelechiidae of the Longarini salt marsh in the “Pantani della Sicilia Sud-Orientale” nature reserve in southeastern Sicily, Italy (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) S. Bella & O. Karsholt Abstract The authors report the results of field research on Gelechiidae from the “Pantano Longarini” salt marsh (southeastern Sicily). The area is located inland to the “Pantani della Sicilia Sud-Orientale” regional nature reserve. A total of twenty-four species are recognized; among the recorded taxa Scrobipalpa peterseni (Povolny´, 1965) is new to Europe, Scrobipalpa bigoti (Povolny´, 1973), Scrobipalpa bradleyi Povolny´ 1971, Scrobipalpa spergulariella (Chrétien, 1910) and Scrobipalpa superstes Povolny´, 1977 are new records for Sicily and Italy, and Syncopacma sangiella (Stainton, 1863) and Scrobipalpa monochromella (Constant, 1895) are new for the Sicilian fauna. -

Integrative Biodiversity Inventory of Ants from a Sicilian Archipelago Reveals High Diversity on Young Volcanic Islands (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

Organisms Diversity & Evolution https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-020-00442-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Integrative biodiversity inventory of ants from a Sicilian archipelago reveals high diversity on young volcanic islands (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Sämi Schär1 & Mattia Menchetti1,2 & Enrico Schifani3 & Joan Carles Hinojosa1 & Leonardo Platania1 & Leonardo Dapporto2 & Roger Vila1 Received: 23 November 2019 /Accepted: 11 May 2020 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2020 Abstract Islands are fascinating study systems for biogeography, allowing researchers to investigate patterns across organisms on a comparable geographical scale. They are also often important for conservation. Here, we present the first bio-inventory of the ant fauna of the Aeolian Islands, a Sicilian volcanic archipelago formed within the last million years. We documented a total of 40 species, including one first record for Italy (Lasius casevitzi). Mitochondrial DNA barcodes were obtained for all 40 taxa sampled on the islands, 13 of which were studied genetically for the first time. Mitochondrial DNA sequences of island specimens were compared with those of conspecific samples from other Aeolian Islands, Sicily and mainland Italy. Standardized photographical documentation of all sequenced specimens is provided. All but one currently recognized species (97.5%) were recovered as monophyletic. Genetic divergence within species ranged up to 12.4% in Pheidole pallidula, although most species had much lower levels of intraspecific divergence. At the scale of the Aeolian Islands, intraspecific genetic divergence varied significantly between subfamilies, with species of the subfamily Myrmicinae showing higher intraspecific divergences than the Formicinae. Comparison of specimens from the Aeolian Islands with conspecific ones from the putative source populations (Sicily and mainland Italy) suggested that the island of Panarea has the genetically most derived myrmeco-fauna among the seven focal Islands. -

A Preliminary Overview of Monitoring for Raptors in Italy

Acrocephalus 33 (154/155): 297−300, 2012 A preliminary overview of List of the Italian Breeding Birds (Peronace et al. 2011). To promote the conservation of some of the monitoring for raptors in Italy most endangered species, the Italian Ministry for the Predhodni pregled monitoringa populacij Environment issued the national action plans for the Lanner Falcon Falco biarmicus feldeggii, the Eleonora’s ptic roparic v Italiji Falcon F. eleonorae and the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus (Andreotti & Leonardi 2007 & 2009, Spina & Leonardi 2007). A regional action plan Arianna Aradis1 & Alessandro Andreotti2 1 has been drafted for the conservation of the Griffon Università degli Studi di Palermo, Dipartimento di Vulture Gyps fulvus in Sardinia (Schenk et al. 2008). Scienze Agrarie e Forestali, Lab. Zoologia applicata, V. le Scienze 13, IT–90128 Palermo, Italy, Monitoring is currently carried out by different actors e–mail: [email protected] and with different aims, especially to evaluate trends of 2 ISPRA - Istituto Superiore per la Ricerca e la common species and species of conservation concern. Protezione Ambientale, Via Cà Fornacetta, 9, IT–40064 Ozzano dell’Emilia, Bologna, Italy, Main players e–mail: [email protected] In Italy, many actors are promoting programmes for raptor monitoring: – State Forestry Corp (CFS), Owing to its great latitudinal extension and – Departments of several Universities (e.g. Milano, environmental heterogeneity, Italy hosts a relatively Palermo, Pavia, Urbino), large number of birds of prey. Considering both – Institute for the Environmental Protection and diurnal and nocturnal species, 47 taxa are known Research – ISPRA, to occur regularly in the country, 31 of which breed – National Parks (e.g. -

8 Nieuwsbrief SPINED 38

8 Nieuwsbrief SPINED 38 UPDATE ON THE SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA, ARANEAE) OF CALABRIA, ITALY Steven IJland Gabriel Metzustraat 1, 2316 AJ Leiden ([email protected]) & Peter J. van Helsdingen European Invertebrate Survey – Nederland, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands ([email protected]) ABSTRACT During the spring of 2017, spiders of 203 identified species were collected in the region of Calabria, Southern Italy. A list of collected species is given. Fifty five species are new records for Calabria. Five species are reported as new for Italy: Pardosa paludicola (Clerck, 1757), Evarcha michailovi Logunov, 1992, Heliophanus simplex Simon, 1868, Dipoena umbratilis (Simon, 1873), and Xysticus macedonicus Šilhavý, 1944. Some species could not be identified as yet: Spermophorides spec., Diplocephalus spec., Lepthyphantes s.l. spec., Pelecopsis spec., and Xysticus spec. The status of Platnickina nigropunctata (Lucas, 1946) is discussed. Key words: Araneae, faunistics, Calabria, Italy, southern Italy INTRODUCTION This paper is the fourth in a series on the spider fauna of southern Italy. The first dealt with a field trip to Gargano in 2011, the second with the surroundings of Castellabate, province Salerno in the region Campania in 2013, the third with the borderland of the regions Basilicata and Calabria in 2015 (see IJland et al. 2012, 2014, 2016) and finally the present paper dealing with a field trip to the provinces of Cosenza and Catanzaro in Calabria in 2017. Fieldwork was carried out during the period 7-19 May 2017 (PvH) and 7-13 May 2017 (SIJ). In total 1059 spiders were collected (437 males, 606 females and 16 juveniles (of recognizable species)). -

(Hemiptera, Fulgoromorpha Et Cicadomorpha)1

Marburger Entomologische Publikationen Band 3 Heft 3 pp. 13 - 98 20.1.2005 CONTRIBUTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE AUCHENORRHYNCHA FAUNA OF CENTRAL ITALY (HEMIPTERA, FULGOROMORPHA ET CICADOMORPHA)1 Adalgisa GUGLIELMINO, Christoph BÜCKLE & Reinhard REMANE Key words: Additional species to the Italian fauna, Autecology, Biogeography, Distribution of species in Italy, Faunistics, Nomenclature, Species set of biotopes, Taxonomy, Vertical distribution. Abstract: The results of several research trips carried out during the past six years in the Central Italian regions of Lazio and Abruzzo (including only few localities in Umbria), covering a variety of biotopes from coastal up to high mountain sites, are presented: 331 species were found, 3 of them - already published separately - new to science (Kelisia italica Guglielmino & Remane, Rhopalopyx cigigas Guglielmino and Euscelis venitala Remane, Bűckle & Guglielmino), 10 of them apparently not yet recorded from Italy, 11 probably first records from continental Italy, even more (38) seem to be first records for "peninsular" Italy ("S" of D'Urso, 1995). These numbers demonstrate the gaps in previous research as well as the need for further research in order to obtain a reliable basis to recognize the change of species distribution or even species set in future times (results e.g. of global warming, pollution etc.). For all species their distribution - altitude, biotopes etc. - in the examined region is discussed, for some of them in comparison with their geographic distribution in Italy, for some taxa taxonomical or nomenclatural remarks are added. An appendix mentions some taxa (3 of them new for peninsular Italy) collected 1977 in Marche/Umbria (Monti Sibillini) and Abruzzo by the third author. -

Araneae.It: the Online Catalog of Italian Spiders, with Addenda on Other Arachnid Orders Occurring in Italy

Fragmenta entomologica, 51 (2): 127–152 (2019) eISSN: 2284-4880 (online version) pISSN: 0429-288X (print version) Research article Submitted: May 20th, 2019 - Accepted: September 8th, 2019 - Published: November 15th, 2019 Araneae.it: the online Catalog of Italian spiders, with addenda on other Arachnid Orders occurring in Italy (Arachnida: Araneae, Opiliones, Palpigradi, Pseudoscorpionida, Scorpiones, Solifugae) Paolo PANTINI 1, Marco ISAIA 2,* 1 Museo Civico di Scienze Naturali “E. Caffi” - Piazza Cittadella 10, I-24129 Bergamo, Italy - [email protected] 2 Laboratorio di Ecologia, Ecosistemi terrestri, Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita e Biologia dei Sistemi, Università di Torino Via Accademia Albertina 13, I-10123 Torino, Italy - [email protected] * Corresponding author Abstract In this contribution we present the Catalog of Italian spiders, produced on the base of the available scientific information regarding spi- der species distribution in Italy. We analysed an amount of 1124 references, resulting in a list of 1670 species and subspecies, grouped in 434 genera and 53 families. Information on spider biodiversity in Italy has increased rapidly in the last years, going from 404 species at the end of XIX century, to 1400 in the 1990s, to the current 1670. However, the knowledge on the distribution of the Italian species is far from being complete and it seems likely that there are still new species to be found or described. The Italian spider fauna is character- ized by the presence of a relevant number of endemic species (342). Concerning families, Linyphiidae show the highest number of spe- cies (477) and the highest number of endemics (114).