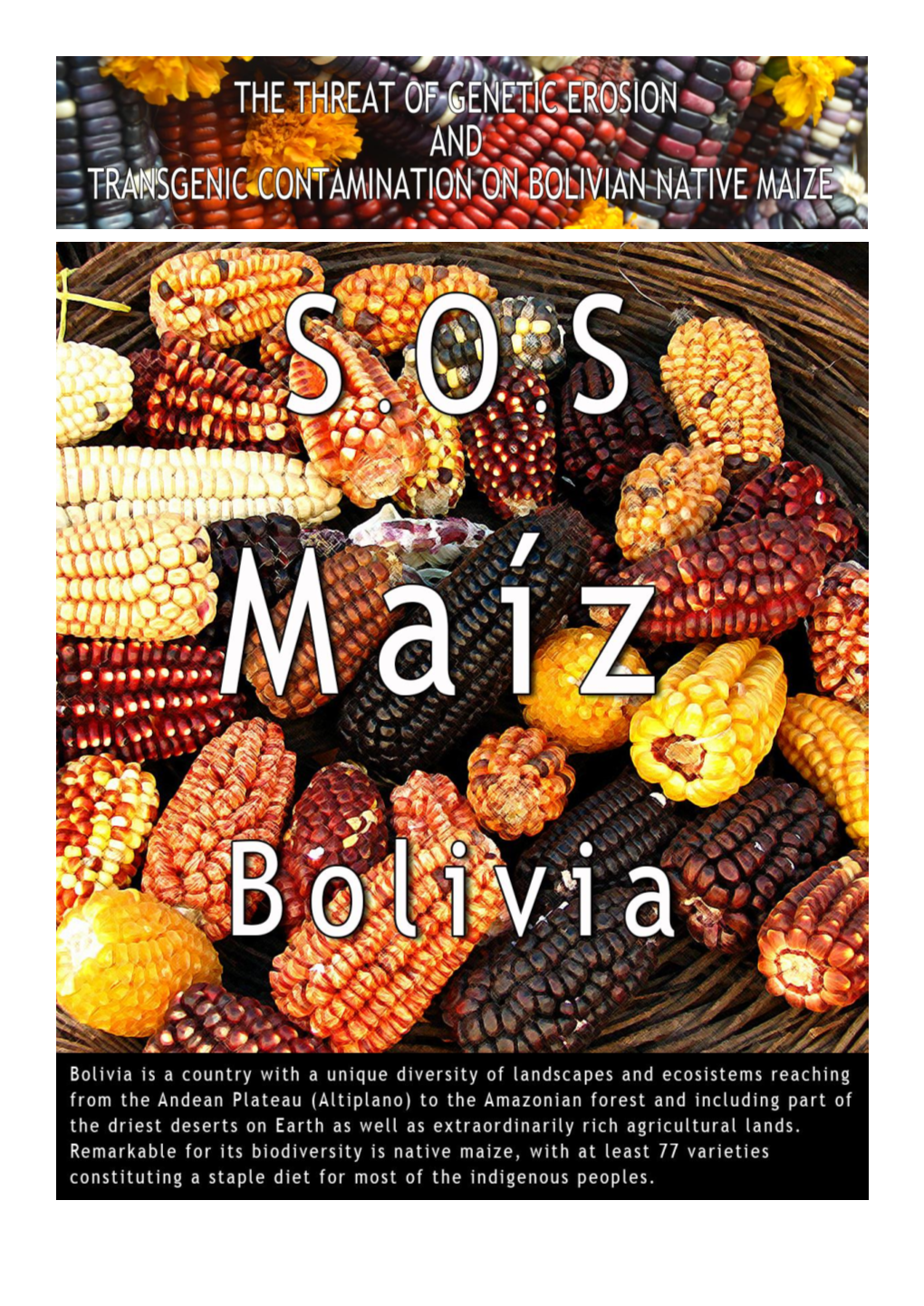

Proyecto De Documental Sobre La Penetración De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Races of Maize in Bolivia

RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E. David H. Timothy Efraín DÍaz B. U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Edgar Anderson William L. Brown NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 747 Funds were provided for publication by a contract between the National Academythis of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made the of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenousfor Strainswork of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E., David H. Timothy, Efraín Díaz B., and U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Calle, Edgar Anderson, and William L. Brown Publication 747 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1960 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS -NRC Publication 453 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramírez E., L. W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. -

Impact of Food Processing on the Safety Assessment for Proteins Introduced Into Biotechnology-Derived Soybean and Corn Crops ⇑ B.G

Food and Chemical Toxicology 49 (2011) 711–721 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food and Chemical Toxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchemtox Review Impact of food processing on the safety assessment for proteins introduced into biotechnology-derived soybean and corn crops ⇑ B.G. Hammond a, , J.M. Jez b a Monsanto Company, Bldg C1N, 800 N. Lindbergh Blvd., St. Louis, Missouri 63167, USA b Washington University, Department of Biology, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1137, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA article info abstract Article history: The food safety assessment of new agricultural crop varieties developed through biotechnology includes Received 1 October 2010 evaluation of the proteins introduced to impart desired traits. Safety assessments can include dietary risk Accepted 10 December 2010 assessments similar to those performed for chemicals intentionally, or inadvertently added to foods. For Available online 16 December 2010 chemicals, it is assumed they are not degraded during processing of the crop into food fractions. For intro- duced proteins, the situation can be different. Proteins are highly dependent on physical forces in their Keywords: environment to maintain appropriate three-dimensional structure that supports functional activity. Food Biotech crops crops such as corn and soy are not consumed raw but are extensively processed into various food frac- Introduced proteins tions. During processing, proteins in corn and soy are subjected to harsh environmental conditions that Processing soy and corn Denaturation proteins drastically change the physical forces leading to denaturation and loss of protein function. These condi- Dietary exposure tions include thermal processing, changes in pH, reducing agents, mechanical shearing etc. -

Ecosystems and Agro-Biodiversity Across Small and Large-Scale Maize Production Systems, Feeder Study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”

Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food” i Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge TEEB and the Global Alliance for the Future of Food on supporting this project. We would also like to acknowledge the technical expertise provided by CONABIO´s network of experts outside and inside the institution and the knowledge gained through many years of hard and very robust scientific work of the Mexican research community (and beyond) tightly linked to maize genetic diversity resources. Finally we would specially like to thank the small-scale maize men and women farmers who through time and space have given us the opportunity of benefiting from the biological, genetic and cultural resources they care for. Certification All activities by Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, acting in administrative matters through Nacional Financiera Fideicomiso Fondo para la Biodiversidad (“CONABIO/FFB”) were and are consistent under the Internal Revenue Code Sections 501 (c)(3) and 509(a)(1), (2) or (3). If any lobbying was conducted by CONABIO/FFB (whether or not discussed in this report), CONABIO/FFB complied with the applicable limits of Internal Revenue Code Sections 501(c)(3) and/or 501(h) and 4911. CONABIO/FFB warrants that it is in full compliance with its Grant Agreement with the New venture Fund, dated May 15, 2015, and that, if the grant was subject to any restrictions, all such restrictions were observed. How to cite: CONABIO. 2017. Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”. -

Antojitos Brasas Calentado Brasas

Antojitos APPETIZERS - Let yourself be seduced by these delicious bites Chicharrón con Arepa Fried pork belly with corn cake 7.50 Papas Criollas Yellow potatoes 3.99 Chorizo con Arepa Corn cake and chorizo 6.50 Arepa Pequeña Small corn cake 1.50 Morcilla con Arepa Blood sausage with corn cake 6.50 Yuca Frita Fried cassava 4 Arepa de Chocolo con Queso 5.50 Tajadas Maduras o Tostones Plantain slices 3.50 Sweet corn cake with cheese Arroz Blanco white rice (Regular & Large) 2.50 - 3.50 Tequeños Fried Breaded Cheese Sticks 2 Frijoles Traditional Criollo Beans (Regular & Large) 3.50 - 7.50 Papas Fritas French fries 3.50 Buñuelos Fried Cheese Balls (Regular & Small) 2 - 1.25 Maduro con Queso Sweet plantain with cheese & 5.50 Bocadillo Ensalada del Dia o Repollo Salad 3.50 - 4.90 Empanadas de Carne, Pollo o Vegetariana 2.50 Antojitos Brasas Beef, chicken or veggie empanadas Arepa con Queso Corn cake with cheese 3.99 Papa Rellena Stuffed Potato 3.50 Sopa Pequeña o Grande Soup Small or Large 5 - 7.50 Mazamorra Con Bocadillo o Panela 4.50 Sweet Corn Potion with Guava Dessert or Panela Desayunos BREAKFAST Includes cofe, hot cocoa or aguapanela. Incluye café, chocolate, o aguapanela. All breakfasts come with a choice of beverage: coffee, hot chocolate, or panela water. Huevos Pericos 12.99 Huevos revueltos con hogado y arepa con queso. / Scrambled eggs with Colombian Creola sauce and corn cake with cheese. Omelettes 12.99 Jamón, queso, champiñones, espinacas, con arepa o pan tostado. / Ham, cheese, mushrooms, spinach, with a side of corn cake or toast. -

Health Benefits of Purple Corn (Zea Mays L.) Phenolic Compounds

Health Benefits of Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Phenolic Compounds Fei Lao, Gregory T. Sigurdson, and M. Monica´ Giusti Abstract: Purple corn (Zea mays L.), a grain with one of the deepest shades in the plant kingdom, has caught the attention of the food industry as it could serve as a source for alternatives to synthetic colorants. Also being rich in phenolic compounds with potential health-promoting properties, purple corn is becoming a rising star in the novel ingredients market. Although having been widely advertised as a “healthy” food, the available information on purple corn health benefits has not yet been well reviewed and summarized. In this review, we present compositional information focused on the potential functional phenolic compounds correlated to health-promoting effects. Studies evaluating potential health-benefitting properties, including in vitro tests, cell models, animal and human trials, are also discussed. This paper emphasizes research using purple corn, or its extracts, but some other plant sources with similar phenolic composition to purple corn are also mentioned. Dosage and toxicity of purple corn studies are also reviewed. Purple corn phenolic compounds have been shown in numerous studies to have potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, anticarcinogenic, and anti-angiogenesis properties. They were also found to ameliorate lifestyle diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases, based on their strong antioxidant power involving biochemical regulation amelioration. With promising evidence from cell and animal studies, this rich source of health-promoting compounds warrants additional attention to better understand its potential contributions to human health. Keywords: anthocyanins, antioxidants, bioactive compounds, dosage, phenolics Introduction orant has been increasing around the world in recent decades, as Purple corn (Zea mays L.), also known as purple maize, is observed by the increasing importation of purple corn and color native to the Andes region of what is now Peru. -

Mazamorra Morada Featured on October 12, 2019 for “Salsa Con Salsa” Demo with Chef Daniela Hurtado

Mazamorra Morada Featured on October 12, 2019 for “Salsa con Salsa” demo with Chef Daniela Hurtado Mazamorra Morada Recipe courtesy of Chef Daniela Hurtado-Castro Yield: 4 cups Ingredients Chica Morada 2 pounds dried purple corn kernels 12 cups water 3 cinnamon sticks 4 cloves 1 apple, cut in chunks 1 pineapple core (you will use the pulp for the mazamorra) Mazamorra 4 cups chicha morada ¼ cup chuño (Peruvian potato starch) ¾ cup water 8 dried and pitted prunes 1 cup Granny Smith apples, diced 1 cup pineapple, diced 2 limes, juiced 1 cup sugar Cinnamon powder for garnish Directions To prepare the mazamorra, you will need to prepare chicha morada first. This will be the base for the preparation of this Peruvian dessert. Place all ingredients in a pot over high heat. When the liquid begins to boil, reduce to a simmer, partially covered, for 2 hours. Strain the liquid into an open container and let cool. Store refrigerated in an airtight container or freeze it for future use. If using the chicha as a refresher, season with sugar and lime juice to taste. Pour the four cups of the chicha morada into a saucepan with the prunes, diced fruit and sugar. Bring to a boil, stir to dissolve the sugar, and reduce to a simmer. In a small bowl, sift the chuño, add the water, and whisk until a smooth paste is formed. Add the chuño paste to the saucepan, keep at a simmer, and stir continuously until the mixture thickens. Turn off heat, stir in the juice of the limes and serve in ramekins or cups. -

Maize As Sovereignty: Anti-GM Activism in Mexico and Colombia

Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE YALE UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 14-15, 2013 Conference Paper #18 Maize as sovereignty: anti-GM activism in Mexico and Colombia Liz Fitting Maize as sovereignty: anti-GM activism in Mexico and Colombia Liz Fitting Conference paper for discussion at: Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue International Conference September 14-15, 2013 Convened by Program in Agrarian Studies, Yale University 204 Prospect Street, # 204, New Haven, CT 06520 USA http://www.yale.edu/agrarianstudies/ The Journal of Peasant Studies www.informaworld.com/jps Yale Sustainable Food Project www.yale.edu/sustainablefood/ in collaboration with Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy 398 60th Street, Oakland, CA 94618 USA www.foodfirst.org Initiatives in Critical Agrarian Studies (ICAS) International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) P.O. Box 29776, 2502 LT The Hague, The Netherlands www.iss.nl/icas Transnational Institute (TNI) PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands www.tni.org with support from The Macmillan Center, the Edward J. and Dorothy Clarke Kempf Memorial Fund and the South Asian Studies Council at Yale University http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/kempf_fund.htm http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/southasia © July 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher and the author. FOOD SOVEREIGNTY: A CRITICAL DIALOGUE - CONFERENCE PAPER #18 Abstract In this conference paper, I consider some of the strengths and weaknesses of the food sovereignty (FS) approach based on my research among anti-GM activists in Colombia and Mexico. -

Léxico De Los Términos Culinarios Y Mexicanismos 1

Léxico de los términos culinarios y mexicanismos 1 Léxico de los términos culinarios y mexicanismos Lexique des termes culinaires et mexicanismes Esther KATZ y Aline Hémond Abreviaturas 1 esp.: término en español 2 náh.: término en náhuatl Lexique 3 Aguacate: esp. (del náh. ahuacatl). Persea americana. En los Andes se llama “palta”. Anthropology of food, S9 | 2014 Katz Esther, Hémond A. Léxico de los términos culinarios y mexicanismos. In : Ariel de Vidas A. (ed.), Hémond A. (ed.), Van't Hooft A. (ed.). Comidas rituales. Anthropology of Food, 2014, 9, art. no 7503 [20 p. en ligne]. ISSN 1609-9168 Léxico de los términos culinarios y mexicanismos 2 Foto 1. Aguacate (Persea americana), Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca. Esther Katz, 2011 4 Ajonjolí: esp. (del árabe andalusí al-ŷulŷulīn). Sesamum indicum. Se llama “sésamo” en otros países. 5 Amaranto: esp. (del náh. huahtli). Semillas de Amaranthus ssp. En el siglo XVI, los españoles prohibieron su uso por su importancia ritual, sobre todo en los sacrificios humanos. 6 Amate: esp. (del náh. amatl). 1) Papel hecho de la corteza batida de árboles, principalmente del género Ficus y de la familia de las Moráceas. 2) Pintura que se hace sobre este papel. 7 Atole: esp. (del náh. atolli). Mazamorra, bebida espesa a base de maíz. 8 Cajete: esp. (del náh. caxitl). Plato hondo de cerámica [véase Foto 21]. 9 Calabaza: esp. Cucurbita spp. Las especies más comunes en México son Cucurbita pepo y Cucurbita argyrosperma. Se comen la pulpa, las semillas (pepitas), las flores y las hojas tiernas. 10 Camote: esp. (del náh. camotli). Túberculo (en general) o túberculo de Ipomoea batatas). -

Private Events Menus for Groups of 25

PRIVATE EVENTS GENERAL EVENT POLICY OVERVIEW OCCUPANCY + EVENT SPACE The 2nd floor at Vista Peru is available for private events on a contract basis and is available for brunch, lunch, dinner, cocktail parties or late night happy hours. Without adjustments, the 2nd floor accommodates 80 people for a cocktail party and 55 people for a seated dinner. Vista Peru is able to accommodate full venue buyouts for groups of up to 140. PRIVATE DINING MINIMUMS • All food and beverage shall be supplied and • Events are booked for a minimum of 2-hour prepared by Vista Peru. No client nor his/her windows. Additional fees may apply for events guests may bring or remove food or beverage that exceed 4 hours. from the event without prior approval Vista Peru. • Food and beverage minimums for a full venue • Cakes prepared by third-party vendors are permitted. buyout are assessed on a case-by-case basis. The cake-cutting fee is $1.25 per person for all pastries brought in from an outside, licensed, • Food and beverage minimums apply to all private commercial bakery. events and vary depending on the night of the week, time of the year and size of the party. BOOKING, DEPOSITS, GUARANTEES • Any group that does not reach the specified food + CANCELLATIONS and beverage minimums will have the difference added to the bill at the conclusion of the event. • Events are booked on a first come, first serve basis and are only considered reserved once a • Food and beverage minimums do not include fully executed contract has been received by applicable tax, service charges, AV rental fees, Vista Peru along with a credit card number/deposit valet (outside vendor), or other incidental charges. -

TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE ORGANISATIONS and RESCUING THEIR Communities

is cookbook is a collection of recipes shared by residents of High Andean regions of Peru STRENGTHENING HIGH ANDEAN INDIGENOUS and Ecuador that embody the varied diet and rich culinary traditions of their indigenous TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE ORGANISATIONS AND RESCUING THEIR communities. Readers will discover local approaches to preparing some of the unique TRADITIONAL PRODUCTS plants that the peoples of the region have cultivated over millennia, many of which have found international notoriety in recent decades including grains such as quinoa and amaranth, tubers like oca (New Zealand yam), olluco (earth gems), and yacon (Peruvian ground apple), and fruits such as aguaymanto (cape gooseberry). e book is the product of a broader effort to assist people of the region in reclaiming their agricultural and dietary traditions, and achieving both food security and viable household incomes. ose endeavors include the recovery of a wide variety of unique plant varieties and traditional farming techniques developed during many centuries in response to the unique environmental conditions of the high Andean plateau. TRADITIONAL Strengthening Indigenous Organizations and Support for the Recovery of Traditional Products in High-Andean zones of Peru and Ecuador HIGH ANDEAN Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean CUISINE Av. Dag Hammarskjöld 3241, Vitacura, Santiago de Chile Telephone: (56-2) 29232100 - Fax: (56-2) 29232101 http://www.rlc.fao.org/es/proyectos/forsandino/ FORSANDINO STRENGTHENING HIGH ANDEAN INDIGENOUS ORGANISATIONS AND RESCUING THEIR TRADITIONAL PRODUCTS Llaqta Kallpanchaq Runa Kawsay P e r u E c u a d o r TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE Allin Mikuy / Sumak Mikuy Published by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (FAO/RLC) FAO Regional Project GCP/RLA/163/NZE 1 Worldwide distribution of English edition Traditional High Andean Cuisine: Allin Mikuy / Sumak Mikuy FAORLC: 2013 222p.; 21x21 cm. -

Mazamorra De Quinua Y Manzana Chef Claus Meyer (Dinamarca) Vanguardia Porciones: 12

Mazamorra de quinua y manzana Chef Claus Meyer (Dinamarca) vanguardia Porciones: 12 Ingredientes: Preparación: HEFBWFOB t -BWFZDPDJOFMBRVJOVBFOBHVBDPOTBMIBTUB NMEFBHVB RVF TF BCSB mKÈOEPTF RVF UPEBWÓB FTUÏ BM DEUBEFTBM EFOUF 4PO BQSPYJNBEBNFOUF NJOVUPT NMEFKVHPEFNBO[BOB 4BRVFMBPMMBEFMGVFHPZEFKFRVFMBRVJOVB TFDPDJOFDPOFMDBMPSSFUFOJEP HEFRVJOVB HEFNBOUFRVJMMB t &OVOBPMMBDPMPRVFMBBWFOB MPTNMEF BHVB FMKVHPEFNBO[BOBZMBTBM ZDBMJFOUFB GVFHPMFOUP Para la cubierta t $VBOEP MPT JOHSFEJFOUFT EF MB QBQJMMB HEFB[ÞDBSEFDB×B DPNJFODFO B VOJSTF BHSFHVF MB RVJOVB HEFNBOUFRVJMMB DPDJEB"KVTUFFMTBCPSDPONBOUFRVJMMBZUBM HEFRVJOVB WF[VOBQJ[DBEFTBM HEFNBO[BOB FODVCJUPT t 1BSBFMBCPSBSMBDVCJFSUB EFSSJUBMBDB×BEF B[ÞDBSFOVOBDBDFSPMBBGVFHPMFOUP"×BEB MBNBOUFRVJMMBZMBRVJOVB ZSFWVFMWB t " DPOUJOVBDJØO FYUJFOEB MB NF[DMB TPCSF QBQFMEFIPSOPZEFKFFOGSJBS t 6OB WF[ GSÓB DØSUFMB FO USP[PT BEFDVBEPT QBSB TV VTP DPNP DVCJFSUB DSVKJFOUF EF MB QBQJMMBEFBWFOBZRVJOVB t 4JSWBMBQBQJMMBFOVOUB[ØO DPOMPTEBEPTEF NBO[BOB KVOUPDPOFMB[ÞDBSZMBDVCJFSUBEF RVJOVBDSVKJFOUF Consejo: 1BSBQSFQBSBSMBB[ÞDBSEF DBOFMBNF[DMFDVDIBSBEBEF B[ÞDBSHSBOVMBEBDPOEFDV- DIBSBEJUBEFDBOFMBFOQPMWP 133 132 Torta de quinua Fuente: Gloria Condori Yapo, Asociación Wiñay Warmi receta tradicional Recetario “El camino de la quinua”, publicado por el Movimiento Manuela Ramos (Perú) Ingredientes: Preparación LHEFIBSJOBEFRVJOVB t4FQBSFMBTDMBSBTEFIVFWPQBSBCBUJSBQVOUPEF HEFNBOUFRVJMMB OJFWF TPCSFEFQPMWPEFIPSOFBS H DEBTEFFTFODJBEFWBJOJMMB t.F[DMF MB NBOUFRVJMMB B[ÞDBS Z ZFNBT IBTUB GPSNBS VOB DSFNB -VFHP BHSFHVF MB IBSJOB -

Conservation and Use of Latin American Maize Diversity: Pillar of Nutrition Security and Cultural Heritage of Humanity

agronomy Review Conservation and Use of Latin American Maize Diversity: Pillar of Nutrition Security and Cultural Heritage of Humanity Filippo Guzzon 1,*, Luis Walquer Arandia Rios 2, Galo Mario Caviedes Cepeda 3, Marcia Céspedes Polo 4, Alexander Chavez Cabrera 5, Jesús Muriel Figueroa 6, Alicia Elizabeth Medina Hoyos 7, Teófilo Wladimir Jara Calvo 5, Terence L. Molnar 1 , Luis Alberto Narro León 8, Teodoro Patricio Narro León 7, Sergio Luis Mejía Kerguelén 9, José Gabriel Ospina Rojas 10, Gricelda Vázquez 11, Ricardo Ernesto Preciado-Ortiz 11, José Luis Zambrano 12 , Natalia Palacios Rojas 1 and Kevin V. Pixley 1 1 International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Texcoco 56237, Mexico; [email protected] (T.L.M.); [email protected] (N.P.R.); [email protected] (K.V.P.) 2 Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agropecuaria y Forestal (INIAF), La Paz, Bolivia; [email protected] 3 College of Sciences and Engineering, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito 170901, Ecuador; [email protected] 4 Centro Fitotécnico y de Semillas Pairumani, Cochabamba, Bolivia; [email protected] 5 Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA), Lima 15024, Peru; [email protected] (A.C.C.); [email protected] (T.W.J.C.) 6 Federación Nacional de Cultivadores de Cereales, Leguminosas y Soya (Fenalce), Pasto 520001, Colombia; [email protected] 7 Estación Experimental Agraria Baños del Inca, Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA), Cajamarca 06004, Peru; [email protected] (A.E.M.H.); [email protected]