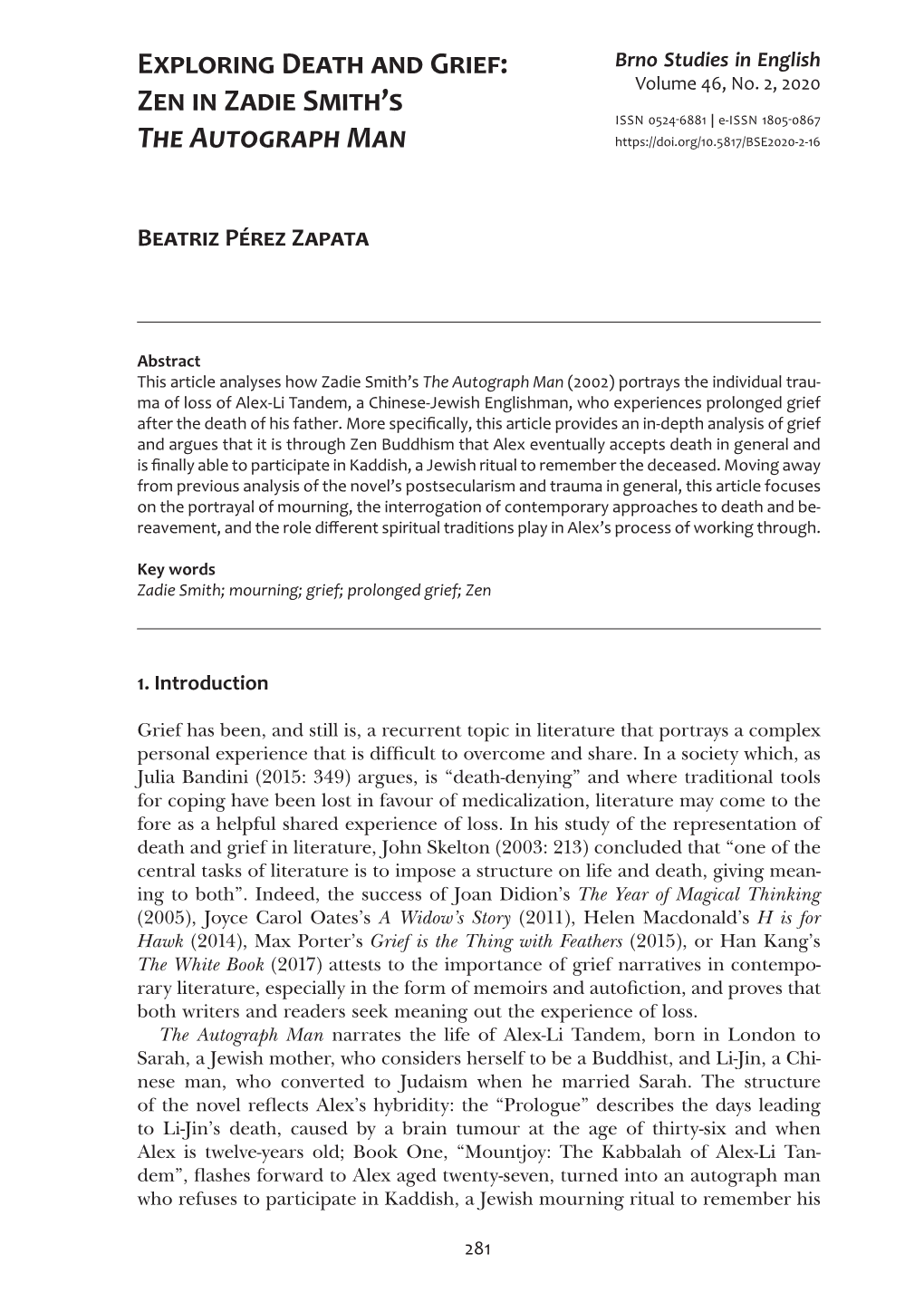

Exploring Death and Grief: Zen in Zadie Smith's the Autograph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gendered, Post-Diasporic Mobilities and the Politics of Blackness in Zadie Smith’S Swing Time (2016)

Suzanne Scafe: Gendered, post-diasporic mobilities and the politics of blackness in Zadie Smith’s Swing Time (2016) ! Gendered, Post-diasporic Mobilities and the Politics of Blackness in Zadie Smith’s Swing Time (2016) Suzanne Scafe Visiting Professor School of Arts and Creative Industries London South Bank University, UK !93 https://sta.uwi.edu/crgs/index.asp UWI IGDS CRGS Issue 13 ISSN 1995-1108 Abstract: Zadie Smith’s novel Swing Time (2016) traverses the geographies and temporalities of the Black Atlantic, unsettling conventional definitions of a black African diaspora, and restlessly interrogating easy gestures of identification and belonging. In my analysis of Smith’s text, I argue that these interconnected spaces and the characters’ uneasy and shifting identities are representative of post-diasporic communities and subjectivities. The novel’s representations of female friendships, mother-daughter relationships, and professional relationships between women, however, demonstrate that experiences of diaspora/post- diaspora are complicated by issues of gender. Forms of black dance and African diasporic music represent the novel’s concerns with mobility and stillness; dance is used by its young female characters as a “diasporic resource” (Nassy Brown 2005, 42), a means of negotiating and contesting existing structures of gender, class and culture. Keywords: Zadie Smith, Swing Time, post-diaspora, dance, mobility, race, gender How to cite Scafe, Suzanne. 2019. “Gendered, Post-Diasporic Mobilities and the Politics of Blackness in Zadie Smith’s Swing Time (2016).” Caribbean Review of Gender Studies, Issue 13: 93-120 !94 Suzanne Scafe: Gendered, post-diasporic mobilities and the politics of blackness in Zadie Smith’s Swing Time (2016) The title of the novel Swing Time (2016) is taken from a 1936 Hollywood musical of the same name, featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. -

Gender Performativity and Societal Boundaries: an Analysis of NW And

Gender Performativity and Societal Boundaries: an Analysis of NW and How to be Both Through the Lens of Judith Butler’s Theory Roos van den Broek 2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Usha Wilbers Title of document: Gender Performativity and Societal Boundaries: an Analysis of NW and How to be Both through the lens of Judith Butler’s Theory Name of course: BA werkstuk Engelse Letterkunde Date of submission: 07-08-2019 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Roos van den Broek 3 Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of NW by Zadie Smith and How to be Both by Ali Smith through the lens of Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity. Three aspects of this theory are examined: the biological sex versus gender distinction, gender performativity and sexuality. The thesis examines the way in which the characters in the novels present themselves, how they behave, and the choices they make. This includes how characters choose to dress themselves, whether they choose to have children, which gender they present themselves as and the kind of relationships they choose to get into. This thesis emphasizes the way that societal boundaries and expectations play a role in the way the characters perform their gender and sexuality. The conclusion of the thesis provides a comparison between the way that both novels reflect Judith Butler’s theory and how the characters differ in their interaction with gender, sexuality and the boundaries and norms of their societies. -

Advance Program Notes an Onstage Conversation with Zadie Smith, Author Tuesday, March 19, 2019, 7:30 PM

Advance Program Notes An Onstage Conversation with Zadie Smith, author Tuesday, March 19, 2019, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. An Onstage Conversation with Zadie Smith, author Moderated by Lucinda Roy, Alumni Distinguished Professor, Department of English at Virginia Tech Presented in partnership with the Department of English Visiting Writers Series and the Women’s Center at Virginia Tech in celebration of its 25th anniversary Biography ZADIE SMITH Novelist Zadie Smith was born in North London in 1975 to an English father and a Jamaican mother. She read English at Cambridge before graduating in 1997. Her acclaimed first novel,White Teeth (2000), is a vibrant portrait of contemporary multicultural London, told through the stories of three ethnically diverse families. The book won a number of awards and prizes, including the Guardian First Book Award, the Whitbread First Novel Award, the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Overall Winner, Best First Book), and two BT Ethnic and Multicultural Media Awards (Best Book/Novel and Best Female Media Newcomer). It was also shortlisted for the Mail on Sunday/John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, the Orange Prize for Fiction and the Author’s Club First Novel Award. White Teeth has been translated into over 20 languages and was adapted for Channel 4 television for broadcast in autumn 2002 and for the stage in November 2018. Smith’s The Autograph Man (2002), a story of loss, obsession, and the nature of celebrity, won the 2003 Jewish Quarterly Wingate Literary Prize for Fiction. -

Multicultural World in Zadie Smith's Recent Novels Multikulturní Svět V

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Diplomová práce Multicultural World in Zadie Smith’s Recent Novels Multikulturní svět v románech Zadie Smith Vypracovala: Bc. Adéla Grenarová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem svoji diplomovou práci na téma Multikulturní svět v románech Zadie Smith vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě - v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných pedagogickou fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne Podpis studentky: ___________________________ Adéla Grenarová Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala paní PhDr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za její připomínky, rady a podporu. Acknowledgement I would like to thank PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. for her comments, advice and support. Abstract Initially, the diploma thesis introduces the overall context of contemporary Anglo- American post-colonial literature and defines its fundamental postulates, such as ethnicity, cultural diversity, hybridity, globalization, and multiculturalism. -

City and Nature in the Work of Zadie Smith

Grey and Green: City and Nature in the work of Zadie Smith Grey and Green: City and Nature in the work of Zadie Smith Freya Graham Introduction In her riotous novel NW (2012), Zadie Smith takes us on a walk through North London. It’s a cacophony: “sweet stink of the hookah, couscous, kebab, exhaust fumes of a bus deadlock. 98, 16, 32, standing room only—quicker to walk!”.1 The narrative continues over a page, taking in “TV screens in a TV shop”, “empty cabs” and a “casino!”.2 Plant and animal life are almost entirely absent, aside from a moment of “birdsong!” and a building surrounded by “security lights, security gates, security walls, security trees”.3 Elements that we may associate with the “natural world” have become part of the architecture of the city, indistinguishable from the man-made lights, gates and walls. NW is so centred on city life that the title itself takes inspiration from a London postcode. The novel follows the lives of four friends—Leah, Natalie, Felix and Nathan— who grow up on the same estate in north-west London. As the friends grow older, their lives overlap in unexpected ways. Leah works in a dead-end job and still lives near her childhood estate; Natalie seemingly triumphs in becoming a successful lawyer and mother; Felix, a former drug addict, is forging a new life; Nathan is involved in organised crime. The novel’s ambitious narrative threads culminate in a tragic chance encounter. NW expands on the themes of class, race, identity and place which Smith first explored in her debut novel, White Teeth (2000). -

I Want to First Define What I Mean by a Novel's Plot

Brown, Luke (2014) Tension between artistic and commercial impulses in literary writers’ engagement with plot. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5158/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Brown 1 Tension between artistic and commercial impulses in literary writers’ engagement with plot Luke Brown Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD in English Literature School of Critical Studies University of Glasgow October 2013 Brown 2 Abstract Tension between artistic and commercial impulses in literary writers’ engagement with plot This thesis explores whether plot and story damage a literary writer’s attempt to describe ‘reality’. It is in two parts: a critical analysis followed by a complete novel. The first third of the thesis is an essay which, after distinguishing between story and plot, responds to writer critics who see plot as damaging to a writer’s attempt to describe ‘the real’. This section looks at fiction by Jane Austen, Henry James, Jeffrey Eugenides, Julian Barnes, Tom McCarthy and Zadie Smith, against a critical background of James Wood, Roland Barthes, David Shields and others including Viktor Shklovsky and Iris Murdoch. -

An Insight Into the Postcolonial Work of Zadie Smith's NW and the Analysis

Faculty of Tourism Final Project Report An insight into the postcolonial work of Zadie Smith’s NW and the analysis of some cultural referents in its translation into Spanish. Laura Martín Jordá Degree in Tourism Academic year 2016-17 Student ID number: 43201427K Tutor-guided work by Caterina Calafat Ripoll Spanish, Modern and Classical Philology Department The University is authorised to include this work in the Institutional Author Tutor Repository for consultation on open access and online broadcasting, Yes No Yes No with academic and research purposes only Work’s keywords: postcolonialism, translation, Zadie Smith, exoticism, hybridity, cultural referents, domestication, foreignization Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................. 2 Introduction......................................................................................................... 2 Methodology used .............................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1.Zadie Smith’s NW & Postcolonialism ................................................. 3 1.1. NW ........................................................................................................ 3 1.2. The author, Zadie Smith ........................................................................ 4 1.3. On Postcolonialism................................................................................ 5 1.4. On Postcolonial Literature .................................................................... -

Social Class As Seen Through the Representation of Language in Zadie Smith's NW

Social Class as Seen through the Representation of Language in Zadie Smith’s NW Vanessa Bengtsson English Studies Bachelor’s Thesis 14 Credits Spring Semester 2021 Supervisor: Petra Ragnerstam Bengtsson 1 Abstract This paper investigates the representation of the working class in Zadie Smith’s novel NW. With the aid of Pierre Bourdieu’s theory on different forms of capital, as well as sociolinguistic theory, the project aims to study the language of the characters as an indicator of their social class belonging. The analysis is divided into three different sections where the characters’ speeches are studied in the context of their age, gender, and ethnicity. This analysis takes a dual approach by first examining what the characters’ language can tell us about their class belonging, and then exploring what effect the use of the representation of working-class speech has on the characters, as well as on the novel at large. The analysis reveals the dissimilarities between the different groups (male and female, old and young, white or non-white), and establishes that through the use of working-class speech, Smith has managed to create a complex and dynamic image of the working class. Key Words: Zadie Smith, NW, Pierre Bourdieu, Forms of Capital, Sociolinguistics, Working- Class Speech. Bengtsson 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Theory and Background ........................................................................................................ -

Inauthenticity and Intertextuality in Zadie Smith's NW

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 42.2 (December 2020): 180-196 e-issn 1989-6840 DOI: http://doi.org/10.28914/Atlantis-2020-42.2.09 © The Author(s) Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence “I am the sole author”: Inauthenticity and Intertextuality in Zadie Smith’s NW Beatriz Pérez Zapata Tecnocampus (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and Valencian International University [email protected] This article examines the role of intertextuality in Zadie Smith’s NW (2012) and the novel’s questioning of authorship, authenticity and identity. Relying on intertextual and postcolonial theories, the article lays bare how Smith’s novel questions the fixity and stability of selves and how she situates herself as an inherently intertextual author disrupted by others and potentially disruptive of (post)colonial ways of being and one that plays with notions of (in)authenticity and originality. For this purpose, the article pays attention to the novel’s intertextual links with the historical case of the Tichborne claimant and Jorge Luis Borges’s fictionalisation of it in the short story “Tom Castro, the Implausible Impostor,” included in the collection A Universal History of Infamy (1933). Moreover, the article focuses on the theorisation of infamy, understood as the disruption of hegemonic narratives brought about by marginal characters and discourses. Keywords: intertextuality; authenticity; authorship; postcolonialism; Zadie Smith . “Soy la única autora”: inautenticidad e intertextualidad en NW de Zadie Smith Este artículo explora el papel de la intertextualidad en la novela NW (2012) de Zadie Smith y cómo esta cuestiona los conceptos de autoría, autenticidad e identidad. -

Swing Time: a Novel by Zadie Smith Ebook

Swing Time: A Novel by Zadie Smith ebook Ebook Swing Time: A Novel currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Swing Time: A Novel please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download book here >> Paperback: 464 pages Publisher: Penguin Books; Reprint edition (September 5, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 0143111647 ISBN-13: 978-0143111641 Product Dimensions:5.4 x 1 x 8.4 inches ISBN10 0143111647 ISBN13 978-0143111641 Download here >> Description: A New York Times bestseller * Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction * Longlisted for the Man Booker PrizeAn ambitious, exuberant new novel moving from North West London to West Africa, from the multi-award-winning author of White Teeth and On Beauty.Two brown girls dream of being dancers—but only one, Tracey, has talent. The other has ideas: about rhythm and time, about black bodies and black music, what constitutes a tribe, or makes a person truly free. Its a close but complicated childhood friendship that ends abruptly in their early twenties, never to be revisited, but never quite forgotten, either.Tracey makes it to the chorus line but struggles with adult life, while her friend leaves the old neighborhood behind, traveling the world as an assistant to a famous singer, Aimee, observing close up how the one percent live.But when Aimee develops grand philanthropic ambitions, the story moves from London to West Africa, where diaspora tourists travel back in time to find their roots, young men risk their lives to escape into a different future, the women dance just like Tracey—the same twists, the same shakes—and the origins of a profound inequality are not a matter of distant history, but a present dance to the music of time. -

Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Monica Ali's Brick Lane

T. C. FIRAT ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ BATI D İLLER İ VE EDEB İYATLARI ANAB İLİM DALI İNG İLİZ D İLİ VE EDEB İYATI B İLİM DALI Individual and Social Conflicts in Multicultural England: Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ DANI ŞMANI HAZIRLAYAN Yrd. Doç. Dr. F. Gül KOÇSOY Seda ARIKAN ELAZI Ğ- 2008 T. C. FIRAT ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ BATI D İLLER İ VE EDEB İYATLARI ANAB İLİM DALI İNG İLİZ D İLİ VE EDEB İYATI B İLİM DALI Individual and Social Conflicts in Multicultural England: Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Bu tez 27 / 03 / 2008 tarihinde a şağıdaki jüri tarafından oy birli ği ile kabul edilmi ştir. Danı şman Üye Üye Yrd. Doç Dr. Doç. Dr. Yrd. Doç. Dr. F. Gül KOÇSOY Abdulhalim AYDIN Mustafa YA ĞBASAN Bu tezin kabulü, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yönetim Kurulu’nun ……../……../……..tarih ve………………………..sayılı kararıyla onaylanmı ştır. Enstitü Müdürü Doç. Dr. Ahmet AKSIN FIRAT UNIVERSITY THE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Individual and Social Conflicts in Multicultural England: Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane Master Thesis SUPERVISOR PREPARED BY Assist. Prof. Dr. F. Gül KOÇSOY Seda ARIKAN ELAZI Ğ-2008 To my mother and my father… TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………. I ÖZET…………………………………………………………………………............ III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………............ V 1.0. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1. The Multi-National and Multi-Cultural Structure in the Twentieth Century 1.1.1 Britain: A Multicultural Country in the Twentieth Century 1.1.2 The End of the British Empire 1.1.3 British Immigration Map 1.2 “Multiculturalism” as a concept 2.0. -

In the Selected Fiction of Zadie Smith

TOPIC OF RESEARCH: Politics of ‘Difference’ and ‘Otherness’ in the Selected Fiction of Zadie Smith Scholar’s Name – Manasvini Rai 2018RHS9032 Supervisor – Dr. Preeti Bhatt Associate Professor Dept. of Humanities and Social Sciences MNIT, Jaipur About the author: Zadie Smith 2 Zadie Smith, originally Sadie Smith, (born October 27, 1975 London, England) Major Works 3 Novels: Swing Time (2016) NW (2012) On Beauty (2005) The Autograph Man (2002) White Teeth (2000) Short Stories: Grand Union: Stories (2019) The Embassy of Cambodia (2013) Martha and Hanwell (2005) Essays: Intimations (2020) Feel Free: Essays (2018) Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (2009) Introduction 4 . Zadie Smith – Life and Work . Interpretations of „Difference,‟ and „Otherness‟ in recent theory . Reflections of the above in Zadie Smith‟s fiction Review of Literature 5 Early critical responses: . Postcolonial elements . Racial connotations . Multicultural London . “Cover girl of the „Multicultural Novel‟” Views on genre and style: . hysterical realism . pastiche . social realism Views on short fiction Views on non-fiction Research Methodology 6 . Core Primary Texts . Novels . Short Fiction . Essays . Review of Literature . Theoretical Basis . Chapterisation . Referencing (MLA 8th Edition) Published Research / Writing 7 . "Race, Culture, and Postcolonial Feminism: Maggie Gee‟s My Cleaner." Journal of Literature and Aesthetics, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, pp. 75-87. "Hunter-hunted and other Binaries: Power-play in Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories.” Journal of the Faculty of Arts 2018-19, Aligarh Muslim University, vol. 11, no. 1, 2019, pp. 154-161. „(Dis)advantage and the Self-Determining „Other‟: Intersectional Politics in Zadie Smith‟s The Embassy of Cambodia.‟ The IUP Journal of English Studies.