THE QUEST for the HISTORICAL GODDESS1 by Mdith M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(S): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(s): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 385-408 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3260509 . Accessed: 11/05/2013 22:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.207.2.50 on Sat, 11 May 2013 22:44:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JBL 105/3 (1986) 385-408 ASHERAH IN THE HEBREW BIBLE AND NORTHWEST SEMITIC LITERATURE* JOHN DAY Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, England, OX2 6QA The late lamented Mitchell Dahood was noted for the use he made of the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts in the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. Although many of his views are open to question, it is indisputable that the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts have revolutionized our understanding of the Bible. One matter in which this is certainly the case is the subject of this paper, Asherah.' Until the discovery of the Ugaritic texts in 1929 and subsequent years it was common for scholars to deny the very existence of the goddess Asherah, whether in or outside the Bible, and many of those who did accept her existence wrongly equated her with Astarte. -

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1 Ancient Near Eastern Pantheons Ammonite Pantheon The chief god was Moloch/Molech/Milcom. Assyrian Pantheon The chief god was Asshur. Babylonian Pantheon At Lagash - Anu, the god of heaven and his wife Antu. At Eridu - Enlil, god of earth who was later succeeded by Marduk, and his wife Damkina. Marduk was their son. Other gods included: Sin, the moon god; Ningal, wife of Sin; Ishtar, the fertility goddess and her husband Tammuz; Allatu, goddess of the underworld ocean; Nabu, the patron of science/learning and Nusku, god of fire. Canaanite Pantheon The Canaanites borrowed heavily from the Assyrians. According to Ugaritic literature, the Canaanite pantheon was headed by El, the creator god, whose wife was Asherah. Their offspring were Baal, Anath (The OT indicates that Ashtoreth, a.k.a. Ishtar, was Baal’s wife), Mot & Ashtoreth. Dagon, Resheph, Shulman and Koshar were other gods of this pantheon. The cultic practices included animal sacrifices at high places; sacred groves, trees or carved wooden images of Asherah. Divination, snake worship and ritual prostitution were practiced. Sexual rites were supposed to ensure fertility of people, animals and lands. Edomite Pantheon The primary Edomite deity was Qos (a.k.a. Quas). Many Edomite personal names included Qos in the suffix much like YHWH is used in Hebrew names. Egyptian Pantheon2 Egyptian religion was never unified. Typically deities were prominent by locale. Only priests worshipped in the temples of the great gods and only when the gods were on parade did the populace get to worship them. These 'great gods' were treated like human kings by the priesthood: awakened in the morning with song; washed and dressed the image; served breakfast, lunch and dinner. -

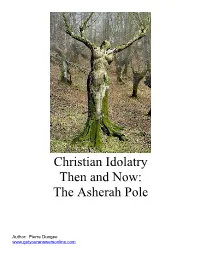

The Asherah Pole

Christian Idolatry Then and Now: The Asherah Pole Author: Pierre Dungee www.getyouranswersonline.com In this short book, we are going to look at the Asherah pole. Just so we have a working knowledge of idolatry, let’s look at what and idol is defined as: noun 1. a material object, esp a carved image, that is worshipped as a god 2. Christianity Judaism any being (other than the one God) to which divine honour is paid 3. a person who is revered, admired, or highly loved We also have the origin of this word, so let’s take a look at it here: o mid-13c., "image of a deity as an object of (pagan) worship," o from Old French idole "idol, graven image, pagan god," o from Late Latin idolum "image (mental or physical), form," used in Church Latin for "false god," o from Greek eidolon "appearance, reflection in water or a mirror," later "mental image, apparition, phantom,"also "material image, statue," from eidos "form" (see - oid). o Figurative sense of "something idolized" is first recorded 1560s (in Middle English the figurative sense was "someone who is false or untrustworthy"). Meaning"a person so adored" is from 1590s. From the origins of the word, you see the words ‘pagan’, ‘false god’, ‘statue’, so we can correctly infer that and idol is NOT a good thing that a Christian should be looking at or dealing with. The Lord has given strict instructions about idols as you can see in scripture here: Leviticus 26:1 - Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the LORD your God. -

Who Were the Daughters of Allah?

WHO WERE THE DAUGHTERS OF ALLAH? By DONNA RANDSALU B.A., University of British Columbia,1982. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (RELIGIOUS STUDIES) We accept this thesis—as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1988 © Donna Kristin Randsalu, 1988 V In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of £gLlfr/OU^ £TUO>eS> The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date Per- n} DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT Who were the Daughters of Allah, the three Arabian goddesses mentioned in the Qur'an and venerated by the pagan Arabs prior to the rise of Islam, and who since have vanished into obscurity? Can we reconstruct information about these goddesses by reference to earlier goddesses of the Near East? It is our intention to explore this possibility through an examination of their predecessors in view of the links between the Fertile Crescent and the Arabian Peninsula. Moving back in time from the seventh century A.D. (Arabia) through the Hellenistic Period (Syro/Phoenicia 300 B.C.-A.D. -

Yahweh Among the Baals: Israel and the Storm Gods

Chapter 9 Yahweh among the Baals: Israel and the Storm Gods Daniel E. Fleming What would Baal do without Mark Stratton Smith to preserve and respect his memory in a monotheistic world determined to exclude and excoriate him? The very name evokes idolatry, and an alternative to the true God aptly called pagan. Yet Baal is “The Lord,” a perfectly serviceable monotheistic title when rendered by the Hebrew ʾādôn or the Greek kurios. Biblical writers managed to let Yahweh and El “converge” into one, with Elohim (God) the common ex- pression, but Baal could not join the convergence, even if Psalm 29 could have Yahweh thunder as storm god. Mark has had much to say about the religion of Israel and its world, and we need not assume Baal to be his favorite, but per- haps Mark’s deep familiarity with Baal suits an analysis of Israel that embraces what the Bible treats as taboo. For this occasion, it is a privilege to contribute a reflection on God’s “early history” in his footsteps, to honor his work, in ap- preciation of our friendship. In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, a text so familiar to Mark that visitors may per- haps need his letter of reference for entry, Baal is the special title of Hadad, the young warrior god of rain and tempest (Smith 1994; Smith and Pitard 2009). Although El could converge with Yahweh and Baal could never name him, gen- erations of scholars have identified Yahweh first of all with the storm (van der Toorn 1999; Müller 2008). Yahweh and Haddu, or Hadad, were never one, but where Yahweh could be understood to originate in the lands south of Israel, as in Seir and Edom of Judges 5:4–5, he could be a storm god nonetheless: (4) Yahweh, when you went out from Seir, when you walked from the open country of Edom, the earth quivered, as the heavens dripped, as the clouds dripped water. -

Anat and Qudshu As the «Mistress of Animals» Aspects of the Iconography of the Canaanite Goddesses

ANAT AND QUDSHU AS THE «MISTRESS OF ANIMALS» ASPECTS OF THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE CANAANITE GODDESSES Izak Cornelius 1. Introduction. In two recent articles, Peggy Day (1991, 1992) argues against the common tendency to describe the Canaanite goddess Anat as a goddess of fertility. She re examines the Ugaritic texts1 in this regard and demonstrates that Anat was rather a «mistress of animals»2, both as a huntress and a protectress. In addition, she discusses three iconographic items from Minet el Beida (figs. 1-3, pi. I), the port of Ugarit. The first item3 (fig. 1 = Keel 1984:fig. 11) is an ivory pixis lid (Louvre AO 11.601) from the 13th century BCE. A goddess, dressed in a skirt, sits on top of a mountain. She holds out plants or corn sheaves to goats flanking her. Many writers have reflected on the Mycenaean style of this item. The second item4 (Winter 1987:fig. 42 = fig. 2) is a golden pectoral (AO 14.714) dating from the 14th century. A naked goddess stands on the back of a lion. She faces the front and holds two horned animals by their legs. Behind her waist are serpents. The background may depict stars. The third item5 (Winter 1987:fig. 41 = fig. 3) is very similar to the previous one6, but the headdress is different and there are no serpents (AO 14.716). The horned animals are suspended in space7. Day takes these three items to be representations of Anat as the «mistress of animals» (1991:143, 1992:187-90). Although her description of Anat as a huntress and a mistress of animals is accepted, the three iconographic items are in need of closer re-examination. -

Transformation of a Goddess by David Sugimoto

Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 263 David T. Sugimoto (ed.) Transformation of a Goddess Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite Academic Press Fribourg Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Publiziert mit freundlicher Unterstützung der PublicationSchweizerischen subsidized Akademie by theder SwissGeistes- Academy und Sozialwissenschaften of Humanities and Social Sciences InternetGesamtkatalog general aufcatalogue: Internet: Academic Press Fribourg: www.paulusedition.ch Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen: www.v-r.de Camera-readyText und Abbildungen text prepared wurden by vomMarcia Autor Bodenmann (University of Zurich). als formatierte PDF-Daten zur Verfügung gestellt. © 2014 by Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg Switzerland © Vandenhoeck2014 by Academic & Ruprecht Press Fribourg Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen ISBN: 978-3-7278-1748-9 (Academic Press Fribourg) ISBN:ISBN: 978-3-525-54388-7978-3-7278-1749-6 (Vandenhoeck(Academic Press & Ruprecht)Fribourg) ISSN:ISBN: 1015-1850978-3-525-54389-4 (Orb. biblicus (Vandenhoeck orient.) & Ruprecht) ISSN: 1015-1850 (Orb. biblicus orient.) Contents David T. Sugimoto Preface .................................................................................................... VII List of Contributors ................................................................................ X -

Canaanite Religion As a Background for Patriarchal and Early Israelite Religion

Canaanite Religion as a Background for Patriarchal and Early Israelite Religion The Ras Shamra texts (site of ancient Ugarit) dating from 1500-1200 B.C.E.) provide important information about Canaanite religion. Ugarit is representative of a larger cultural continuum that included 2nd-1st millennium Syria-Palestine and formed the background for the formation of the tribes of Israel. These texts attest to aspects of Canaanite culture and mythology that the ancient Israelites alternately shared, adopted, modified and rejected. The Ugaritic gods and goddesses 1. El. Literally, "god" but also the personal name for the head of the Canaanite pantheon and council of the gods until overthrown by Baal. He is also called: King, Creator of All, Father of years, Kind, Compassionate. He is represented as a patriarchal god who dwells in a tent. EI appears throughout Semitic cultures as Allah (=El) in Arabic religion and EI/Elohim in the Hebrew Bible. 2. Baal. Literally "master" but also "husband." Son of the grain god Dagan, Baal was a storm god. By 1000 B.C.E. he had become the chief diety and head of the Canaanite pantheon. He is featured in a fertility myth in which he is killed by Mot, the god of death, and then restored to life (a Canaanite version of the myth of a dying and rising god that is linked to the cycle of nature and agriculture). Another story tells of a battle between Baal the storm god and the chaotic watery demon Yamm (reminiscent of the battle between Marduk and Tiamat in Mesopotamian myth and reflected in Israel's demythologized version of creation in which God's wind moves over the watery deep, and in God's parting the Reed Sea by a blast from his nostrils. -

Canaanite Pantheon ADON: (Adonis) the God of Youth, Beauty and Regeneration

Canaanite Pantheon ADON: (Adonis) The god of youth, beauty and regeneration. His death happens arou nd the love affair between him and the goddess Ashtarte which another god envied . He, in the form of a wild boar, attacks and kills Adonis and where his blood f ell there grows red poppies every year. However, as Ashtarte weaps for his loss, she promises to bring him back to life every spring. AKLM: Creatures who attacked Baal in the desert. Some say these creatures are gr asshopper-like. ANATH: This was a Love and War Goddess, the Venus star. She is also known for sl aying the enimies of her brother Baal much in the same way Hathor slaughtered mu ch of mankind (Anath is heavily related to Hathor). After the Defeat of Mavet an d Yam, a feast was thrown for Baal. Anath locked everyone inside, and proceeded to slay everyone (as they had all been fickle toward Baal with both Mavet and Ya m, as well as Ashtar). Baal stopped her and conveinced her that a reign of peace is what was needed. She also has confronted Mavet and was responsible for Baal' s liberation from the underworld. She is the twin sister of Marah. Daughter of A sherah. She is also known as Rahmay- "The Merciful", and as Astarte. Astarte is the Canaanite Name of Ishtar; just as Ishtar is the Babylonian Name of Inanna. I n all cases the Name means, simply, "Goddess" or "She of the Womb". ARSAY: She of the Earth. Daughter of Baal. An underworld Goddess. -

THE MOTHER Is 1% Yahweh 99% Asherah, 1% Allah 99% “We,”

7/17/2021 Gmail - THE MOTHER: THE MOTHER is 1% Yahweh 99% Asherah, 1% Allah 99% “We,” ... AADHA AKASH <[email protected]> THE MOTHER: THE MOTHER is 1% Yahweh 99% Asherah, 1% Allah 99% “We,” ... 1 message Jagbir Singh <[email protected]> Sat, Jul 17, 2021 at 11:23 AM To: AADHA AKASH <[email protected]> THE MOTHER is 1% Yahweh 99% Asherah, 1% Allah 99% “We,” 1% Jerusalem 99% Kuntillet Ajrud; 1% Pope Francis 99% Francesca Stavrakopoulou, 1% Genesis 99% Big Bang, 1% Purgatory 99% Jewelled Island, 0% death 100% moksha. (July 17, 2021) July 16, 2021 Hi all, We need to persevere regarding the “false god hiding the real God both from others and from ourselves”. Who is this God of Power that we read about in the earliest biblical texts? Is this the God within ourselves? It can’t be. He is described in terms of an external tribal male God, not as the indwelling universal Mother God: “The Song of Moses in Deuteronomy 32 indicates that Yahweh was believed to have been one of the children of the Canaanite deity, El Elyon (God Most High). The song describes how the nations were formed and it says the peoples of the Earth were divided up according to the number of El Elyon’s children. Yahweh was Israel’s patron. In other words, the best evidence suggests that Yahweh or Jehovah did not begin as the “only true God”. He did not begin by being regarded as the Creator of the world. -

Baal (Deity) Texts As a King Enthroned Atop Mount Zaphon and Is Granted a Palace Upon His Triumph in His Battles I

B Baal (Deity) texts as a king enthroned atop Mount Zaphon and is granted a palace upon his triumph in his battles I. Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible/Old Testament with the forces of Death (the god Mot) and chaos II. Judaism (cf. the deities Yamm [Sea], Lithan [Leviathan], and III. Islam Tannin). Along these same lines, the iconography IV. Literature of Ugarit and of the wider Levantine orbit portrays V. Visual Arts Baal-Haddu/Hadad as a warrior wielding a club of thunder and/or a spear of lightning (see fig. 6). In I. Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible/ other instances, Baal is depicted as slaying a ser- Old Testament pent. In the series of texts commonly designated the Baal Cycle, the theme of Baal’s kingship is domi- 1. Baal in the Ancient Near East. The Hebrew nant. As the victor over the powers of death and term baal is a common Semitic noun for “hus- chaos, he is the giver of life. It should be pointed band,” “owner,” or “lord,” but as early as the 3rd millennium BCE, the term was also employed to out, however, that this theme as depicted in Ugari- refer to a deity in a god-list from Abu Salabikh. The tic myth is associated exclusively with the deity’s term is also attested at Ebla in personal names and ability to provide rain and ensure agricultural fertil- toponyms. Yet, it is difficult at times to ascertain ity. Nowhere in the myth is this role of Baal explic- which of the possible uses of the term baal is in itly connected with human fertility, let alone some view. -

Pagan Religion in Canaan

Pagan Religion In Canaan In the land of Canaan, there were numerous so-called gods and goddesses which the pagans worshipped. The main gods were called El, Ba’al and Dagon and the main goddess was Asherah or Ashtoreth. The word “El” means “God”. “El” was the chief high god of many gods and goddesses of the Semitic peoples in Canaan. The Ugaritic myths taught that El’s female consort was Asherah. In pagan myths Asherah was also Ba’al’s female consort 1 or his mother. 2 Dagon was god of the Philistines. Dagon was portrayed as having a human upper body and a fish lower body. The major rite of Dagon worship was human sacrifice. Archaelogical information on Ba’al Ba’al was the most popular male god of the Canaanites. In the Ras Shamrah texts from Ugarit in North Syria in about 1380 B.C., the name Ba’al is found about 240 times. In these texts, Ba’al is called Hadad about 20 times or is used in a compound form with Hadad. Like Ba’al, Hadad was a Semitic god of storms and fertility. Throughout the Middle East, Hadad was not always equated with Ba’al but in the Ras Shamrah texts he is. The symbol of both Ba’al and Hadad were bulls. Bulls were symbols of fertility. Ba’al and Hadad were fertility gods. The Ras Shamrah texts call Ba’al the son of the god Dagon. The Ras Shamrah tablets and statuettes and stelae found at Ugarit provide an abundance of information about Ba’al.