Overview of the Cover-Up by Archdiocese Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nightmare on 17Th Street

SEXUAL ABUSE OF MINORS BY CLERGY IN THE ARCHDIOCESE OF PHILADELPHIA OR THE NIGHTMARE ON 17TH STREET Thomas P. Doyle, J.C.D., C.A.D.C. February 20, 2017 1 Introductory Remarks The Archdiocese of Philadelphia is one of the oldest ecclesiastical jurisdictions in the United States. It was erected as a diocese in 1808 and elevated to an archdiocese in 1875. It has long had the reputation of being one of the most staunchly “Catholic” and conservative dioceses in the country. The Archdiocese also has the very dubious distinction of having been investigated by not one but three grand juries in the first decade of the new millennium. The first investigation (Grand Jury 1, 2001-2002) was prompted by the District Attorney’s desire to find factual information about sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in the Archdiocese. The second grand jury (Grand Jury 2, 2003-2005) continued the investigation that the first could not finish before its term expired. The third grand jury investigation (Grand Jury 3, 2010-2011) was triggered by reports to the District Attorney that sexual abuse by priests was still being reported in spite of assurances by the Cardinal Archbishop (Rigali) after the second Grand Jury Report was published that all children in the Archdiocese were safe because there were no priest sexual abusers still in ministry. Most of what the three Grand Juries discovered about the attitude and practices of the archbishop and his collaborators could be found in nearly every archdiocese and diocese in the United States. Victims are encouraged to approach the Church’s victim assistance coordinators and assured of confidentiality and compassionate support yet their stories and other information are regularly shared with the Church’s attorneys in direct violation of the promise made by the Church. -

Commonwealth V. Lynn

filfru - UPREME COURT JAN 2 7 IN THE 2014 SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA EASTERN EASTERN DISTRICT OPTRICT EAL 2014 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Petitioner V. RECENED WILLIAM J. LYNN 3AN 2 7 2011 URT SUPR6MEDISTRICT PETITION FOR ALLOWANCE OF AWEAL Petition to appeal the published decision of the Superior Court of December 26, 2013 at 2171 EDA 2012, vacating the July 24, 2012 judgment of sentence for endangering the welfare of children in the Court Of Common Pleas Of Philadelphia County, Trial Division, Criminal Section, At CP-51-CR-0003530-2011. HUGH J. BURNS,JR. Chief, Appeals Unit RONALD EISENBERG Deputy District Attorney EDWARD F. McCANN,JR. First Assistant District Attorney R.SETH WILLIAMS District Attorney 3 South Penn Square Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Questions presented 1 Order in question 2 Statement of the case 3 Reasons for granting the application L The Superior Court erred in holding that a church official vvho systematically reassigned pedophile priests in a manner that risked further sexual abuse of children did not endanger the welfare of children. 14 II. If, as the Superior Court held, it was legally impossible for defendant to endanger the vvelfare of children in his individual capacity,the evidence vvas sufficient to prove his guilt as an accomplice. 26 Conclusion 35 Appendix A: Published decision of the Superior Court Appendix B: Trial court opinion TABLE OF CITATIONS Commonwealth v. Bachert, 453 A.2d 931 (Pa. 1982) 26 Commonwealth v. Booth, 766 A.2d 843 (Pa. 2001) 15 Cornmonvvealth v. Coccioletti, 425 A.2d 387(Pa. 1981) 26 Commonwealth v. -

Journey of Hope

2008 Annual Report Journey of Hope . Renewing Reinforcing Revitalizing The Catholic Community of Brooklyn and Queens Since its founding in 1853, the faithful of the Diocese of Brooklyn have grown as stewards of God’s gifts. This sense of stewardship is as real today as it was 155 years ago. Through the faithful family and friends of the Diocese of Brooklyn and the generosity shared with the Alive in Hope capital campaign YOU the people of our diocese established the Alive in Hope Foundation— the Catholic Community Foundation of the Diocese of Brooklyn. Today, the diocese is home to 1.5 million Catholics from 167 countries. With your help, the Alive in Hope Foundation is able to fulfill its mission of meeting the needs of this diverse, urban population. INTERNATIONAL CATHOLIC STEWARDSHIP COUNCIL AliVE in Hope Foundation of the Diocese of BrooKLYN Is Herby Awarded an Honorable Mention In Recognition of Their Excellence in Total Foundation Effort ICSC ANNUAL CONFERENCE BOSTON, MA Reverend Monsignor John J. Bracken, Chairman Dear Friends: On behalf of the Board of Directors for the Alive in them a great sense of hope. It is our collective privilege to Hope Foundation (AIHF), I am so honored and pleased serve our benefactors as the conduit of your benevolence. to present a stewardship report for the 2007 fiscal year Your gifts touch the heart of so many including us who of our ten-year-old foundation. The journey of hope have the fortune to see your largesse in action. began in 1998. Since then, over $21 million has been Know as we enter the next decade of our existence, we distributed in grant, aid and scholarships throughout give thanks to those who made the first decade one the populous boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. -

Saint Mary's News

ST. CATHARINE OF SIENA PARISH READING, PENNSYLVANIA JULY 30, 2017 BISHOP-ELECT SCHLERT’S ORDINATION / Saint Mary’s News INSTALLATION INFORMATION In celebration of the Ordination and Installation of Bishop-elect Alfred Schlert as the Fifth Bishop of Allentown, the Diocese will be Mass Schedule having two liturgical services: Saturday, August 5th - 3:30 p.m. - Peg Solemn Vespers at which the Bishop-elect will make a Cappel, (1st Anniversary) Profession of Faith and the Oath of Fidelity is scheduled for Sunday, - August 6th - 10:30 a.m. - Wednesday, August 30 at 7:00 PM at the Cathedral of Saint Catharine of Siena in Allentown (1825 Turner Street, Allentown, Lascoskie Family PA. 18104). This event is open to the public. As the Allentown Fair will be occurring, all parking will be at St. Thomas More Church (1040 Flexer Avenue, Allentown, PA. 18105). Continuous shuttles will be running beginning at 5:00 PM. Light refreshments Help Needed - Volunteers in the Parish Activity Center will follow and everyone will have a chance to greet the Bishop-Elect. are needed to clean St. Mary’s Church next Sunday, The Mass of Ordination will be held at the Cathedral of Saint Catharine of Siena on Thursday, August 31 at 2:00 PM. Because August 6th after the 10:30 of space limitations at the Cathedral, attendance at this event is by invitation only. The Ordination/Installation will be broadcast live on a.m. Mass. Service Electric and Blue Ridge Cable TV locally. Efforts are underway to have it broadcast nationally as well. It will also be livestreamed on the Diocesan Facebook page : New Eucharistic Minister and Lector www.Facebook.com/DioceseofAllentown schedules can be picked up after Masses this weekend in the sacristy. -

Bishop Edward Cullen Papers MC 103 Finding Aid Prepared by Patrick Shank

BIshop Edward Cullen Papers MC 103 Finding aid prepared by Patrick Shank This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 20, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Catholic Historical Research Center (CHRC) of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia November 2018 6740 Roosevelt Blvd Philadelphia, PA (215) 904-8149 [email protected] BIshop Edward Cullen Papers MC 103 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Accession 1990.139................................................................................................................................. 7 Accession 2011.009.............................................................................................................................. -

Today We Salute Our Graduates, Who Stand Ready to Take the Next Steps Into the Future. and We Honor the Students, Faculty, Staff

Today we salute our graduates, who stand ready to take the next steps into the future. And we honor the students, faculty, staff, parents and friends who are overcoming the challenges of this extraordinary year and enabling SMU to continue to shape world changers. ORDER OF EXERCISE WELCOME CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREE Kevin Paul Hofeditz, Ceremony Marshal Doctor of Humane Letters: Max Glauben Presented by Elizabeth G. Loboa PRELUDIAL MUSIC AND FANFARES Escorted by Hope E. Anderson ’17 Imperial Brass CONFERRING OF DEGREES IN COURSE ACADEMIC PROCESSIONAL Please refrain from applause until all candidates have been presented. The audience remains seated during the academic processional and recessional. Conferred by R. Gerald Turner Jodi Cooley-Sekula, Chief Marshal Presented by Elizabeth G. Loboa Bradley Kent Carter, Chief Marshal Emeritus Deans and Director of the Schools and Programs Thomas B. Fomby, Chief Marshal Emeritus Gary Brubaker, Director of SMU Guildhall Darryl Dickson-Carr, Platform Marshal Marc P. Christensen, Dean of Lyle School of Engineering Barbara W. Kincaid, Procession Marshal Jennifer M. Collins, Dean of Dedman School of Law David Doyle, Jr., Assisting Procession Marshal Nathan S. Balke, Marshal Lector Thomas DiPiero, Dean of Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences Elena D. Hicks, Marshal Lector Craig C. Hill, Dean of Perkins School of Theology Kevin Paul Hofeditz, Senior Associate Dean of Meadows School of the Arts The Gonfalons Stephanie L. Knight, Dean of Annette Caldwell Simmons School of The Platform Party Education and Human Development Timothy Rosendale, Past-President of the SMU Faculty Senate and Tate Matthew B. Myers, Dean of Cox School of Business Mace Bearer James E. -

A Fond Thank You to Bob Young by Fr

FALL /WINTER 2014/2015 A Fond Thank You to Bob Young By Fr. Michael Murphy didn’t just stop at the dream; he brought School and he tendered his resignation it to fulfillment. In the spring of 2014, as chair of the committee. At Bob’s We welcome you to participate in our new Spot the Dot game. Go to Pastor, St. Dorothy Church the school website to download and print your Dot’s Dot picture or carry St. Dorothy Parish hosted the first ever recommendation, and in consultation it with you on your smart phone. Then take a photo with your Dot’s Dot It is hard to believe that our Celebration of Catholic Schools and the with our school principal Mrs. Louise in interesting places or with interesting people. Send us your photos to be Development Committee has been in Arts. Local parish schools, high schools, Sheehan, Mr. Peter McGahey was invited featured on the website and perhaps a future issue of the newsletter. We existence more than ten years. The and even Catholic universities performed to succeed Bob. Peter was already a know our Dot’s students and alumni are leading interesting lives, we’d genesis of the committee came during at the festival. They sang, played hand member of the Development Committee love to hear about your adventures! a period of concern about our school’s bells, performed a scene from a musical, and he assumed this responsibility enrollment. The parish became aware of entertained us with jazz music, and, without hesitation. I am confident that the need to market the school and also to overall, showcased the many talents Peter will continue to build upon the trumpet the many blessings it brings to of Catholic school students. -

Bishop Schlert Celebrates Pro-Life Mass of Reparation in Ashland

“The Allentown Diocese in the Year of Our Lord” VOL. 30, NO. 2 JANUARY 25, 2018 Catholic Charities For 45th Anniversary of Roe vs. Wade Announces Honorees Bishop Schlert Celebrates Pro-Life for 2018 Gala Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Allentown – which Mass of Reparation in Ashland provided vital services for more than 20,000 individuals By TAMI QUIGLEY and families last year throughout Berks, Carbon, Lehigh, Staff writer Northampton and Schuylkill counties – will hold its 11th Annual Gala with the goal of increasing fundraising for “Today we continue to the less-fortunate in our communities. commemorate the tragic This year’s gala will be Sunday, March 4 at 5:30 p.m. Supreme Court decision at the University Center of DeSales University, Center Roe vs. Wade that legalized Valley. The evening will feature live and silent auctions, a abortion,” said Bishop Al- special appeal, presentations to the honorees and a special fred Schlert, main celebrant raffle. and homilist of a Pro-Life This year’s Gala honorees are Mass of Reparation Jan. 21 Msgr. John McCann, pastor of Im- at St. Charles Borromeo, maculate Conception BVM Church, Ashland. Douglassville, and the Honorable This year marks the 45th William and Rosemary Ford, parish- anniversary of the Jan. 22, ioners of the Cathedral of St. Catha- 1973 Roe vs. Wade U.S. Su- rine of Siena, Allentown. preme Court decision that legalized abortion in the Msgr. McCann United States. Msgr. McCann graduated from Father Paul Rothermel, Marian High School, Tamaqua and pastor of St. Charles Bor- began his college studies at Allen- romeo, concelebrated the 11 town College of St. -

Allentown Farewell Homily Most Reverend John O. Barres, STD

1 Allentown Farewell Homily Most Reverend John O. Barres, STD, JCL Bishop-designate Diocese of Rockville Centre (Long Island, New York) January 22, 2017 In Matthew 4, we see that John the Baptist’s arrest and suffering are linked to the image of Jesus as the Suffering Servant described in Isaiah. John the Baptist prepares the Way of the Lord and his suffering and martyrdom prepare the way for Christ’s own sacrificial death on the Cross. To show his love for the Baptist, Jesus echoes his words: “Repent for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” How easy it can be to get comfortable with and increasingly blind to our daily patterns of pride, envy, anger, lust, gluttony, sloth and greed. But the Word of God is ever new, powerful and unpredictable. We have heard this phrase “Repent for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” many times before but when we open the horizons of our lives to the Holy Spirit, we hear it new every time. Today, for instance, we hear this soul-stirring call to repentance at a unique moment in our marriage and family, our life as a priest, religious or deacon, our life as a young person trying to discern our future. We hear it at a unique moment of the Church’s history with Pope Francis inspiring all of us to touch the wounds of Christ in suffering humanity and reminding us that “families transform the world and history” with Christ’s love and mercy. And we hear it together as I am called from the fishing nets that we have cast together in Schuylkill, Carbon, Berks, Northampton and Lehigh Counties in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the nets of Nassau and Suffolk Counties in New York and the rough surf of the Atlantic Ocean. -

Freerepublic.Com/Focus/F-News/2252808/Posts

Notre Dame Prof: I Think Obama Will Do More For The Pro-Life Cause ... http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/2252808/posts Free Republic News/Activism Browse · Search Topics · Post Article Skip to comments. Notre Dame Prof: I Think Obama Will Do More For The Pro-Life Cause Than Any President In History! Fox News ^ | May 17, 2009 Posted on Sunday, May 17, 2009 4:25:53 PM by Free ThinkerNY Professor of Sociology at Notre Dame (Richard Williams), responds to FOX News contributor, Father Jonathan Morris. (Excerpt) Read more at youtube.com ... TOPICS: News/Current Events KEYWORDS: bho44; bhoabortion 1 posted on Sunday, May 17, 2009 4:25:54 PM by Free ThinkerNY [ Post Reply | Private Reply | View Replies] To: Free ThinkerNY If he means driving the masses to the pro-life position through his extreme pro-death policies, he is right. 2 posted on Sunday, May 17, 2009 4:27:08 PM by Ol' Sparky (Liberal Republicans are the greater of two evils) [ Post Reply | Private Reply | To 1 | View Replies] To: Free ThinkerNY Obama will do the same for opposition fund raising. 3 posted on Sunday, May 17, 2009 4:27:24 PM by AU72 [ Post Reply | Private Reply | To 1 | View Replies] To: Free ThinkerNY I agree. BO will do the same for the pro life movement as he has done for gun sales. 4 posted on Sunday, May 17, 2009 4:30:53 PM by Man50D (Fair Tax, you earn it, you keep it!) [ Post Reply | Private Reply | To 1 | View Replies] To: Free ThinkerNY The Bishops are certainly speaking out in a pro-life way! The bishops who have so far expressed disapproval of Notre Dame's invitation to Obama (in 1 of 14 5/24/2009 10:12 AM Notre Dame Prof: I Think Obama Will Do More For The Pro-Life Cause .. -

The Avery Files Big Trial

2/29/2016 "The Avery Files" | Big Trial | Philadelphia Trial Blog This is Google's cache of http://www.bigtrial.net/2012/03/averyfiles.html. It is a snapshot of the page as it appeared on Jan 31, 2016 08:11:34 GMT. The current page could have changed in the meantime. Learn more Full version Textonly version View source Tip: To quickly find your search term on this page, press Ctrl+F or ⌘F (Mac) and use the find bar. T U E S D A Y , M A R C H 2 7 , 2 0 1 2 F O L L O W U S Follow @BigTrialBlog "The Avery Files" T R I A L S "Father Ed" Avery liked to hang out at Smokey Joe's and drink beer with college kids. He was into sleepovers with altar boys. He also preferred to spin records as a DJ rather than say Mass. Archdiocese Sex Abuse Trial Philadelphia Mob Trial In Common Pleas Court over the past two days, the prosecution opened up "The Avery Files" more than 100 confidential documents dealing with accusations of sex abuse against Father Inky Death Match Edward V. Avery. Scarfo Fraud Trial The priest, a defendant in the archdiocese sex abuse case, pleaded guilty last week to conspiracy to endanger the welfare of a child, and involuntary deviant sexual intercourse with a 10year P O P U L A R P O S T S old, and faces a prison sentence of 2 1/2 to 5 years. But that guilty plea didn't end Father Ed's role in the ongoing archdiocese sex abuse case. -

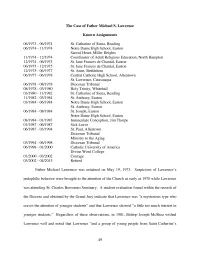

The Case of Father Michael S. Lawrence Known Assignments

The Case of Father Michael S. Lawrence Known Assignments 06/1973 - 06/1974 St. Catharine of Siena, Reading 06/1974 - 11/1974 Notre Dame High School, Easton Sacred Heart, Miller Heights 11/1974 - 12/1974 Coordinator of Adult Religious Education, North Hampton 12/1974 - 06/1975 St. Jane Frances de Chantal, Easton 06/1975 - 12/1975 St. Jane Frances de Chantal, Easton 12/1975 - 06/1977 St. Anne, Bethlehem 06/1977 - 06/1978 Central Catholic High School, Allentown St. Lawrence, Catasauqua 06/1978 - 08/1978 Diocesan Tribunal 08/1978 - 03/1980 Holy Trinity, Whitehall 03/1980 - 11/1982 St. Catharine of Siena, Reading 11/1982 - 03/1984 St. Anthony, Easton 03/1984 - 06/1984 Notre Dame High School, Easton St. Anthony, Easton 06/1984 - 08/1984 St. Joseph, Easton Notre Dame High School, Easton 08/1984 - 01/1987 Immaculate Conception, Jim Thorpe 01/1987 - 06/1987 Sick Leave 06/1987 - 03/1994 St. Paul, Allentown Diocesan Tribunal Ministry to the Aging 03/1994 - 06/1998 Diocesan Tribunal 06/1998 - 01/2000 Catholic University of America Divine Word College 01/2000 - 03/2002 Courage 03/2002 - 04/2015 Retired Father Michael Lawrence was ordained on May 19, 1973. Suspicions of Lawrence's pedophilic behavior were brought to the attention of the Church as early as 1970 while Lawrence was attending St. Charles Borromeo Seminary. A student evaluation found within the records of the Diocese and obtained by the Grand Jury indicate that Lawrence was "a mysterious type who craves the attention of younger students" and that Lawrence showed "a little too much interest in younger students." Regardless of these observations, in 1981, Bishop Joseph McShea wished Lawrence well and noted that Lawrence "and a group of young people from Saint Catherine's 49 Parish will be making a retreat on the weekend of November 20d1 -22nd." The Bishop's salutations are contained within his November 5, 1981, letter to Lawrence on the subject.